In this series, 'Conservation in focus', Simon Gillespie, Director of Simon Gillespie Studio, explores the art of conservation. In each article, Simon looks in depth at a particular technique or tool that is crucial to conservators and explores the challenges – and triumphs – associated with their everyday work.

A large part of a conservator's work is undoing the work of past restorers.

Now, conservation has become a professionalised career, with formalised training through degree courses, journals and conferences, university departments to research materials and methods, and professional governing bodies setting ethical standards. All of this enables conservators to achieve their goal: to preserve artworks now and for the future.

Previously, treatment of artworks was carried out by people who, for all their good intentions, had limited training and knowledge of the possible effects of their intervention. It was common practice, if a painting had a small damage, to simply paint over the whole of the affected area using oil paint of a similar colour, sometimes covering up details in the process. The overpaint may age differently to the original paint, and what might have been acceptable at one stage could now look glaringly mismatched: it's no wonder that a masterpiece by a great artist can end up looking like a later copy.

A large part of my work as a conservator on Britain's Lost Masterpieces has been to remove restorers' overpaint to reveal the brushwork and colours of the original. It is best practice to carry out precise retouching only to the area of damage.

Removing the overpaint can be very challenging: overpaint is often very similar to the original paint, and if it was applied at an early stage in the artwork's life, it will have aged similarly. It can be very difficult to remove without risking damage to the original paint layer. I am proud to say that my team is trained in the latest and safest methods for removing not only varnishes but also overpaint: some pictures we have worked on would not have been possible to clean safely even ten years ago. It can be a very time-consuming process, but a very rewarding one.

For example, on removing a blanket of green overpaint from Spring by Pieter Brueghel the younger, numerous details of pastoral life were uncovered: chickens and sheep in the field, linen being dried. In the painting's pair, Winter, I have previously mentioned that the artist's signature was found beneath an overpainted log. This picture is a perfect example of the damage overpaint can cause to a picture's attribution: the overpaint was applied in 1969, according to the collection's records, and the painting was demoted in 1973. If that overpaint hadn't been applied four years earlier, the signature would still have been visible and so the painting less likely to have been overlooked.

In the case of Pollok House's portrait of the Duke of Buckingham by Rubens, various areas – including the whole of the background – had been overpainted: under the microscope, it was possible to see a varnish layer between the original grey-blue background and the later overpaint.

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

17th C

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

This portrait was originally made by Rubens as a sketch for a full-length equestrian portrait. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, unfinished artworks and sketches were not appreciated as they are today and so would be 'finished off' to appeal to the tastes of the market – a finished work would command higher prices than a sketch. Where overpaint made the artwork look like a later copy, removing it allowed the artist's skilled brushwork to shine again. On Britain's Lost Masterpieces, Bendor said 'it's one of the best cleanings of a painting I've ever seen.' I must agree it was a very pleasing result.

View this post on Instagram

In the case of Jacob Jordaens' painting of Meleager and Atalanta (at Swansea Museum), the overpaint also appears to have been applied for cosmetic reasons – perhaps to make this sketch look more like a finished picture to make it more appealing to a potential buyer. The original sky had been overpainted a garish blue in some areas and the horses' manes had been overpainted with pink streaks. Atalanta's white dress had been painted red, with a nipple painted onto her breast.

Seeing the original picture, bare of later interference, revealed a previously unknown aspect of Jordaens' work: it showed that the large-scale composition Meleager and Atalanta, in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, had been based on this very detailed, though sketchy, model.

Sometimes there are good reasons for later paint to have been applied. For example, Petworth House's portrait of a young cardinal – thought to be by Titian – had suffered such terrible damage that the bottom section had previously been removed, cutting off part of the original hand. A new section of canvas had been stitched on.

Onto this, the past restorer had painted a wooden ledge (possibly because that was easier to paint than trying to recreate the cardinal's robe) and repainted the hand, not very skilfully.

Overpaint had also been applied elsewhere on the picture, and so its true quality was largely concealed. After our treatment, which included sympathetic retouching, expert Peter Humfrey stated that the work was 'Titianesque': too good to be just 'workshop of Titian' however the lack of documentation meant that the work could not be firmly ascribed to Titian himself. Therefore, it is now known as 'attributed to Titian', which was nonetheless a pleasing result.

Portrait of an Unknown Young Cardinal

16th C

Titian (c.1488–1576) (attributed to)

Similarly, the overpaint on the face of the full-length portrait of a young man by Zoffany had been applied to conceal damage in the forehead, but unfortunately was done a little clumsily; our restoration has been much more sympathetic.

Sometimes the overpaint is intentionally deceptive: when Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate came to the studio from the National Museum of Wales as a possible Botticelli, one of the first things we observed was that the cracks in the blue background of the picture were not real cracks but had been painted on. This was not a good first sign, as it suggested a past attempt to make a relatively recent picture look old!

When Gwendoline Davies purchased the picture in the twentieth century, it was considered to be by Botticelli, but shortly after it arrived at the museum, experts began to doubt the attribution, and it was downgraded to the status of a later copy by an unknown artist.

What made them suspicious? The arched background was out of place, and layers of overpaint and old varnish over the Madonna and child obscured the painting's quality. But despite this unpromising first look, there were hints that the picture might be one of great quality.

Removing the dirt, old varnish and hardened overpaint was a painstaking process, largely carried out under the microscope. It was also discovered that the arched background was the work of a later artist, added in the early twentieth century, probably to hide the fact that the painting had been significantly reduced in size from a larger work. After discussion with the museum, it was decided to keep the added background to reflect the painting's history. Our treatment revealed a work of extraordinary quality, with areas, including the Madonna's head, painted in Botticelli's distinctive manner.

Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate

c.1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) (studio of)

The removal of the overpaint from the face of George Oakley Aldrich was a very moving moment: the artist, assumed to be Pompeo Batoni, with his characteristic skill in rendering life-like details, had painted the sitter's facial disfigurement. This is extremely rare in portraiture as artists and sitters largely tended to want to leave out any imperfections – much as professional photographers (or indeed, you and I) might do today with airbrushing on our photographs and selfies.

At some point in the painting's history, this facial disfigurement had been concealed with later overpaint, perhaps applied by someone who thought that the uneven appearance of the skin was a damage in the paint itself, or whose idea of beauty made them decide to conceal the sitter's imperfection.

We are very pleased to have brought the portrait back to how it was intended by the artist and sitter. The fact that Aldrich was a doctor may have informed his decision to show himself as he truly was, without shame. It's a wonderfully honest and human portrait by a man who contributed to advances in medical sciences.

George Oakley Aldrich (1721–1797)

c.1750

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) (attributed to)

Overpaint can make a dramatic difference even if applied in small areas: the portrait of Frances Vaughan by Mary Beale in Carmarthenshire County Museum only had a small bit of what we call 'strengthening' on her forehead and nose, where someone had decided to define these areas more strongly, creating a bulbous forehead and nose-ring effect.

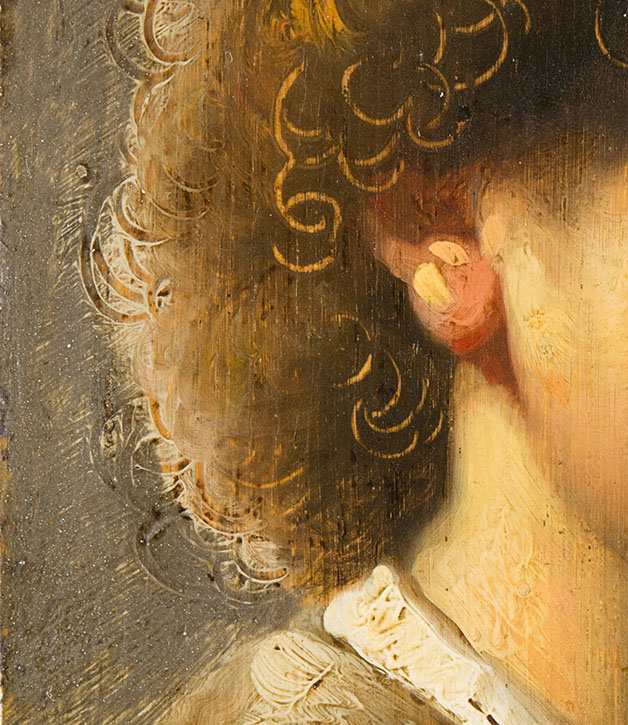

Likewise, removing the overpaint that had been applied over the curls in Rembrandt's Self Portrait at the Age of 22 had a dramatic effect on its appearance.

The most staggering instance of extensive overpaint we've had so far on Britain's Lost Masterpieces has been the Autumn scene at Birmingham Museums. This painting was a prime example of one that belongs to the nation but was not on display due to its poor condition.

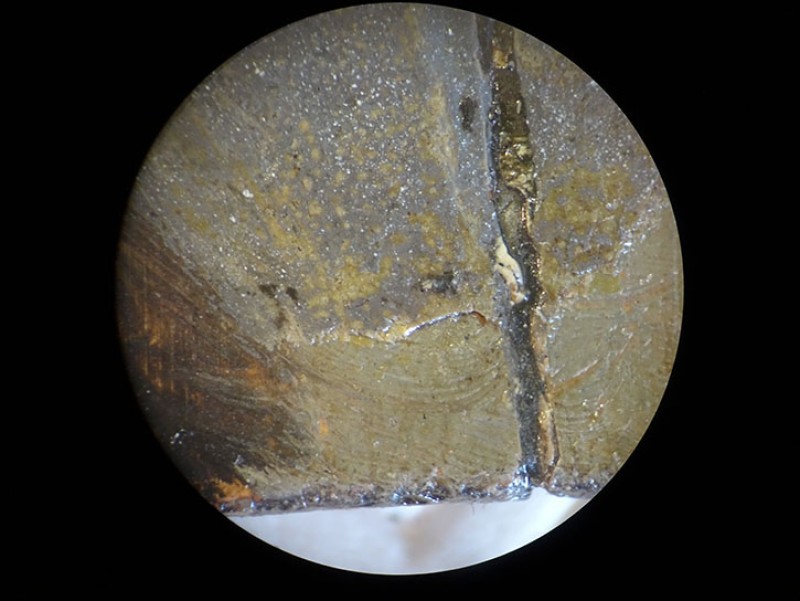

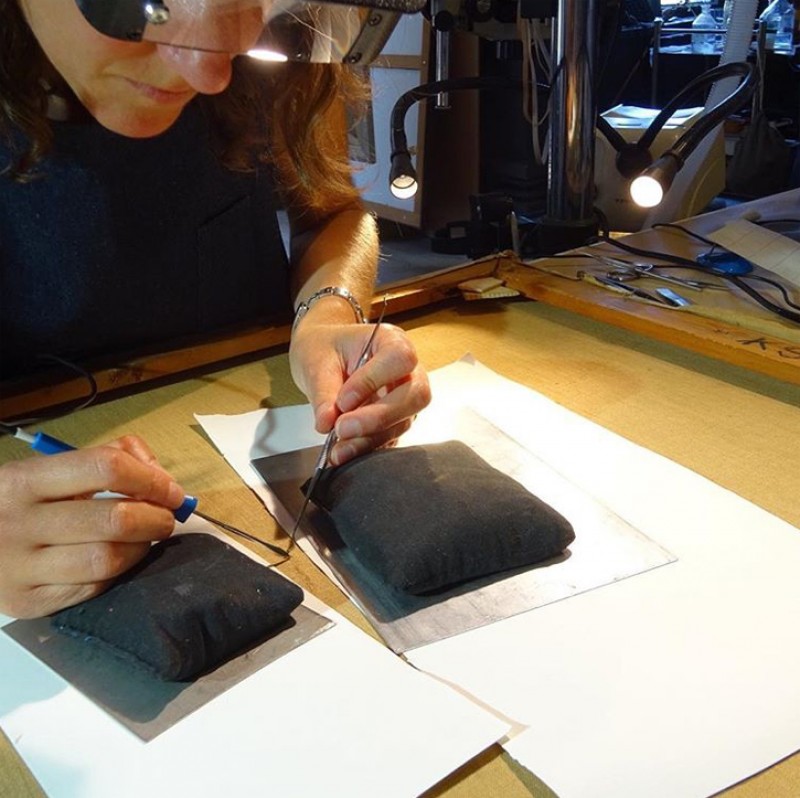

Examining a plank of the 'Autumn' panel under a microscope

The picture was not only broken into two pieces and covered in dirt and yellow varnish, but it also had audacious repainting applied by an artist or restorer, possibly in the eighteenth century, covering more than half the original composition. They had added buildings and trees on top of the artist's composition in a scale that was not at all consistent with the original. The central portion of the painting was mostly overpaint, creating a heavily wooded landscape. Evidently, someone had thought that they could better the existing picture.

The overpaint was in very poor condition, with areas bubbling and flaking. Although it was titled Autumn, it was very difficult to determine what lay beneath the frosted varnish.

However, the small sections of the original design that were visible allowed us to appreciate that there must be something important lying beneath. With our tailor-made system for safely cleaning off layers of later paint, we gradually – over the course of several weeks – revealed original paint in good condition.

The hours of painstaking work have certainly been worthwhile. After treatment, the picture reveals – in marvellous detail – the lives of Flemish agricultural workers through the process of cider making: harvesting the apples, putting them through a cider press and storing the cider in barrels.

Autumn has now been dated to 1605–1610 and an attribution made to two artists: the landscape by Joos de Momper the younger and the figures by the workshop of Jan Brueghel the elder – possibly by the hand of Jan Breughel the younger working in his father's studio. Flemish artists often specialised in specific types of painting and the collaboration of portraitist and landscape painter demonstrated in Autumn is typical. It exhibits, in one sublime work of art, both the supreme characterisation and attention to detail of Breughel the elder alongside the accomplished landscape painting of De Momper.

The removal of the varnish and overpaint meant that the original perspective down the road into the village can now be admired, with little groups of people engaged in lively scenes. The heavy foliage (a later addition) was removed to reveal a hillside behind the village with tiny figures, just one millimetre tall, ploughing the field and with another church tower in the distance.

In the far distance, we see a river with sailing boats on it. When painting his landscapes, De Momper famously used varying tones of brown, green and blue progressively to characterise the recession of space. Blue pigments naturally fade over time, which is why the hillside, river and sky appear yellow-green-grey today.

At all times, we have to accept the limitations of our current methods and materials (even though they have improved dramatically over the years), and in some cases, it may not be possible to remove old overpaint without running the risk of damaging the original paint layer.

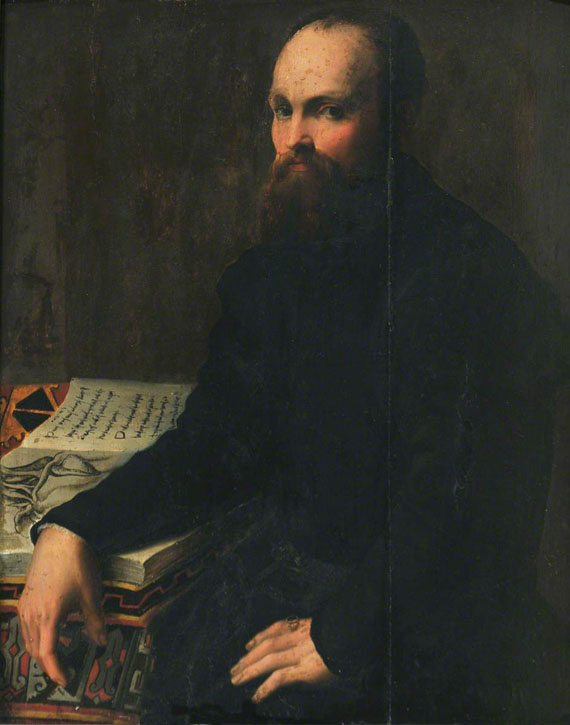

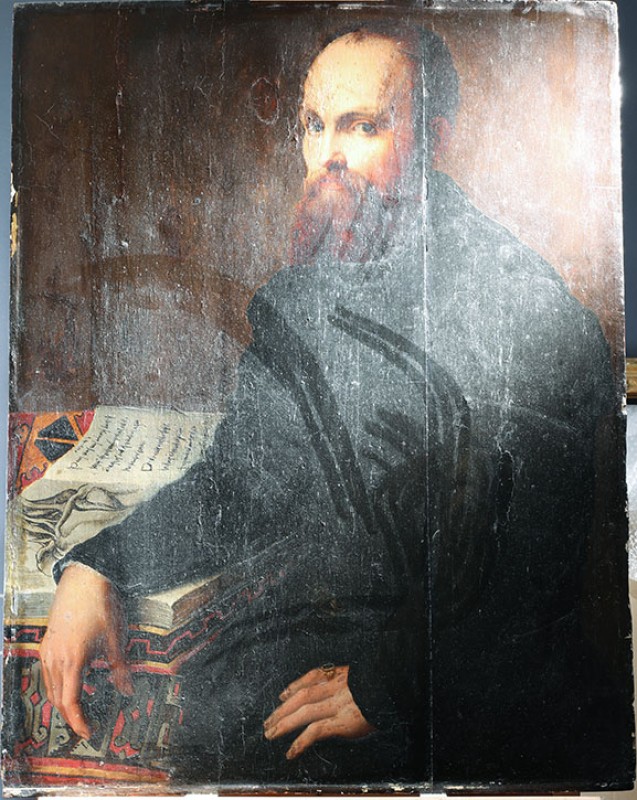

When we worked on a portrait at the National Trust's Tatton Park, we found that it was possible to remove the topmost layers of crude overpaint in the areas of the black costume, but it was concluded – after testing – that it was not possible to remove the lower layer of overpaint in that area (which was effectively a reworked costume) without damaging the delicate original layers.

After consultation with conservators at the National Trust, it was decided to leave the costume as it is now, with the artist's original paint obscured beneath the overpaint. Interestingly, small areas of the original were revealed at the edges of the sleeve: we could reveal a small tassel. When cleaning the background, in what was previously an undistinguished brown area revealed an architectural detailing of a niche within which the sitter is placed, giving the painting a greater three-dimensional feel.

Realdo Matteo Colombo (1515–1559)

1530–1569

Francesco Salviati (1510–1563)

Bendor had initially thought that perhaps Parmigianino had painted this portrait, but the architectural detail was one of the clues that led to an attribution to Francesco Salviati.

Simon Gillespie, Director at Simon Gillespie Studio

Previous: Varnish removal

Next: Sympathetic retouching