(Born Siegen, Westphalia, 28 June 1577; died Antwerp, 30 May 1640). Flemish painter, draughtsman, designer, and diplomat, the greatest and most influential figure in Baroque art in northern Europe. He was born in Germany, the son of a scholarly lawyer from Antwerp who left the city to escape religious persecution (he had Protestant sympathies). In 1587, soon after his father's death, he returned to Antwerp with his mother; he had been baptized a Calvinist in Germany, but he became a devout Catholic. From about 1590 he studied successively with three fairly undistinguished masters: Tobias Verhaecht (1561–1631), who was a distant relative, Adam van Noort (1562–1641), and Otto van Veen. The first two could teach him no more than the local tradition, but van Veen was a man of some culture, who had spent several years in Rome, and he no doubt inspired his pupil with a desire to visit Italy. Rubens became a master in the Antwerp painters' guild in 1598, and after working with van Veen for two more years he set out for Italy in 1600.

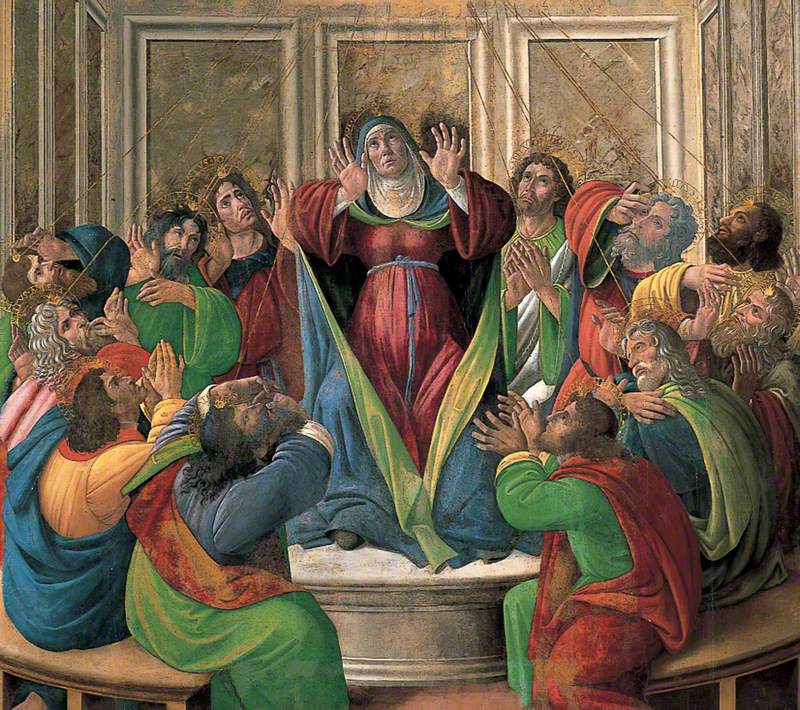

On learning that his mother was seriously ill, Rubens returned to Antwerp in 1608, but she died before he arrived. Italy had become his spiritual home (he usually signed himself ‘Pietro Pauolo’) and he considered returning for good, but his success in Antwerp was so immediate and great that he remained there, and in spite of his extensive travels later in his career he never saw Italy again. In 1609 he was appointed court painter to the Archduke Albert and his wife the Infanta Isabella, the Spanish governors of the Netherlands (Isabella was the daughter of Philip II of Spain—see Habsburg); he was allowed to remain in Antwerp, even though the court was in Brussels. In the same year he married the 17-year-old Isabella Brant, the daughter of an eminent Antwerp lawyer. The portrait of himself and his wife that he painted to mark the union (Alte Pin., Munich) gives a wonderful picture of Rubens on the threshold of his prodigious career—handsome, vigorous, and dashingly self-confident. In the next few years he established his reputation as the pre-eminent painter in northern Europe, his first two resounding successes being the huge triptychs of the Raising of the Cross and the Descent from the Cross (1610–11 and 1611–14, Antwerp Cathedral), which showed his mastery of history painting in the Grand Manner and the immense vigour of his style.

The demand for Rubens's work was extraordinary, and he was able to meet it only because he ran an extremely efficient studio. It is not known how many pupils or assistants he had, because as court painter he was exempt from registering them with the guild. The idea of his running a sort of picture factory has been exaggerated, but even a man of his seemingly inexhaustible intellectual and physical stamina (he habitually rose at 4 a.m.) could not carry out all the work involved in his massive output with his own hands. He both collaborated with established artists (Jan ‘Velvet’ Brueghel, Jordaens, Daniel Seghers, Snyders, and others) and retouched pictures by pupils, the degree of his intervention being reflected in the price. Generally his assistants (of whom van Dyck was the most illustrious) did much of the work between the initial oil sketch and the master's finishing touches. Modern taste has tended to admire these sketches and his drawings (in which his personal touch is evident in every stroke of brush, chalk, or pen) more than the large-scale works, but Rubens himself would surely have found this attitude hard to comprehend, for the sheer size and grandeur of the finished paintings gives them an extra, symphonic dimension. His capacity for collaboration and delegation was an expression of his warm and well-balanced personality as well as of his management skills: he was generous towards his fellow artists and in spite of his immense worldly success he aroused little professional jealousy.

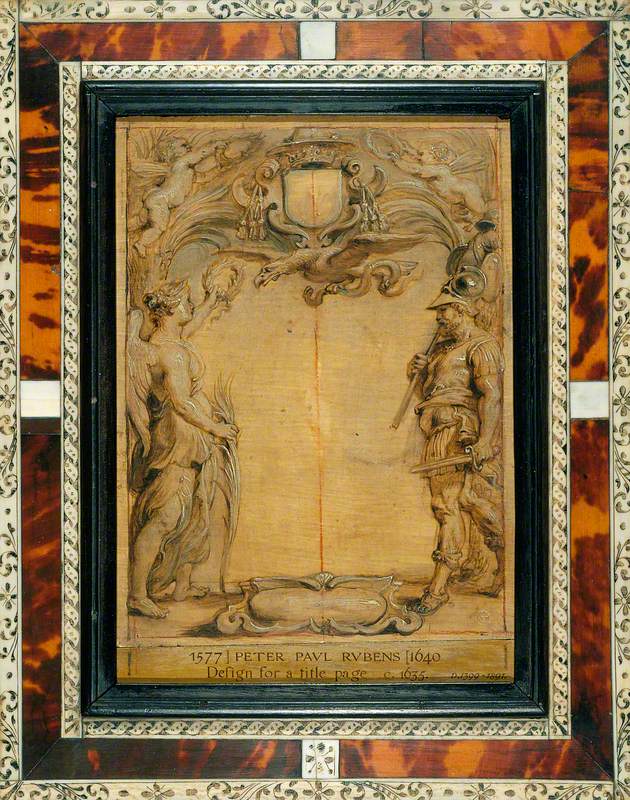

Rubens not only painted virtually every type of subject then known, but also designed tapestries, book illustrations, and decorations for festivals, as well as giving visual directives for sculptors, metalworkers, and architects. ‘My talents are such’, he wrote in 1621, ‘that I have never lacked courage to undertake any design, however vast in size or diversified in subject.’ So huge was his output, indeed, that it is difficult to put a figure on it: the Corpus Rubenianum, the first complete catalogue of his work using all the resources of modern scholarship, began publication in 1968 and is still incomplete (34 volumes are scheduled).

His biggest commission in Flanders was for the decoration of the Jesuit church in Antwerp (a building he may also have had a hand in designing), but almost all his work there was destroyed by fire in 1718. From outside Flanders, those who sought his services included the royal families of France, England, and Spain. For Marie de Médicis (mother of Louis XIII of France) he did a series of 24 enormous paintings on her life (1622–5, Louvre, Paris); for Charles I of England he painted a series of canvases representing the reign of his father James I (completed 1635) for the ceiling of the Banqueting House in London (the only one of his major decorative schemes still in situ); and for Philip IV of Spain he produced more than a hundred mythological and animal pictures (1636–8, mainly executed by collaborators) for a royal hunting lodge, the Torre de la Parada, near Madrid. Some of the paintings were destroyed in 1710 when the building was sacked during the War of the Spanish Succession, but many are now in the Prado, Madrid, and more than fifty of Rubens's oil sketches also survive.

After the death of the Archduke Albert in 1621, Rubens became a trusted adviser to the Infanta Isabella. In that year a twelve-year truce between the Spanish Netherlands (Flanders) and its northern neighbour the Dutch Republic (Holland) came to an end and Rubens was entrusted with diplomatic missions aimed at securing a lasting peace between the countries. In this he was unsuccessful, but he did play an important role in the preliminary stage of ending hostilities between Spain (Flanders' overlord) and England (Holland's ally). He visited Spain in 1628–9 (when he met Velázquez) and England in 1629–30, and he was knighted by the kings of both countries (Charles I in 1630, Philip IV in 1631) for his part in the peace negotiations. In his diplomatic role his courtly manners and linguistic skills were put to good use—apart from Flemish and Italian, he knew French, German, Latin, and Spanish.

Rubens found the political work a solace following the death of his beloved wife in 1626, but after he remarried in 1630 he had a desire to ‘remain home all my life’, and although he stayed reluctantly involved in diplomacy until Isabella's death in 1633, he never went abroad again. His new wife, 16 when he married her, was Hélène Fourment, daughter of a rich silk merchant and the niece of his first wife. The second marriage was as happy as the first, and Rubens's love of his family shines through many of his late paintings (Hélène Fourment with Two of her Children, c.1636, Louvre). In 1635 he bought a country house, the Château de Steen, between Brussels and Malines, and in his final years he developed a new passion for painting landscapes—wonderfully ripe works that led Constable to extol ‘the joyous and animated character’ he impressed on ‘the level, monotonous scenery of Flanders’, and to declare that ‘In no branch of the art is Rubens greater than in landscape.’ Superb examples are in the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection, London.

In his lifetime Rubens was described as ‘prince of painters and painter of princes’ and at his death he was mourned not just as a supreme artist but also as one of the great men of the age. His influence in 17th-century Flanders was overwhelming, and it was spread elsewhere in Europe by his journeys abroad and by pictures exported from his workshop, and also through the numerous engravings he commissioned of his work. In later centuries, his influence has also been immense, perhaps most noticeably in France, where his greatest admirers included Watteau, Delacroix (who called him ‘that Homer of painting, that father of warmth and enthusiasm’), and Renoir. Because of the unrivalled variety of his work, artists as different in temperament as these three could respond to it with equal enthusiasm.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)