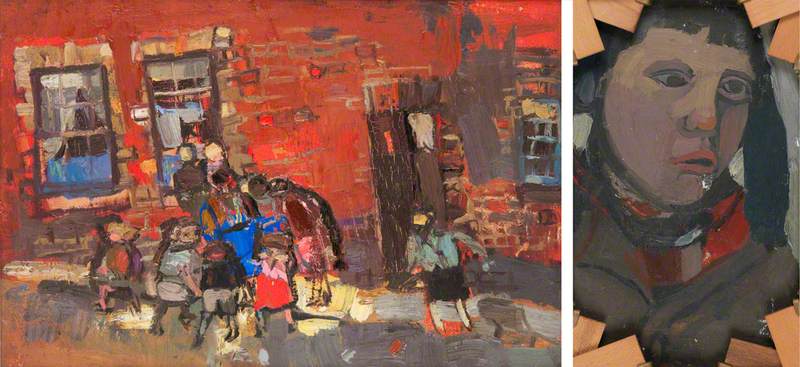

A group of children linger in front of a sun-drenched tenement. Rays of light are absorbed by deep orange stone, turning it the colour of Irn Bru. Adults peer into a blue pram – behind them, a dark wooden door creaks ajar.

The urban tableau of Red Tenement is one of many depicted by Joan Eardley, a painter best known for her rural landscapes but for whom Scottish tenement buildings were a leitmotif of her early life and work.

Red Tenement (recto), Head of a Child (verso)

1958

Joan Kathleen Harding Eardley (1921–1963)

The location of Eardley's painting Red Tenement (recto), Head of a Child (verso), is almost certainly Townhead in the east end of Glasgow, an area in which she rented a studio during the 1950s. It was common to see the artist wandering through the neighbourhood pushing a pram filled with paints and an easel until a scene caught her eye.

She encountered local youngsters happy to be painted for sixpence and a cheese and syrup sandwich, and she encountered tenements, which she committed to canvas just as faithfully as her animate subjects. Eardley's paintings remain a powerful expression of how housing was and is a fundamental part of being human, in particular within working-class communities.

Few buildings have as textured a back story as the tenement, and fewer still have earned a reputation variously as a statement on class, a symbol of socialism and ultimately a national treasure. Little wonder, then, that so many artists use the tenement not only as a backdrop but as a feature in its own right.

These days, Eardley's Townhead is architecturally denuded, a strange mishmash of 1970s tower blocks, post-modern university buildings and voids left by flattened period houses. The fine grain of its Victorian street pattern is long gone, and yet, in the post-war era, this was the land of the tenement.

Today these blocks of ginger, blonde or grey sandstone flats comprise about 40 per cent of Scotland's housing stock, largely in urban postcodes, although many have been lost.

We see ghosts of the built environment revived in Red Tenement and Townhead Close, which features another gaggle of children dressed in fireman red, clutching each other and spilling out onto the pavement. Here, the street acts as a soap opera, a place into which life cannot help but bleed.

To understand why the tenement holds the attention of artists, we must rewind to the seventeenth century, when huge tenements were first built in Edinburgh's Old Town. Some, such as the five-storey Gladstone's Land, with its ground-level carriage car park, have been saved for the nation. This is now run by the National Trust for Scotland, along with The Tenement House in Glasgow.

In James Ferrier Pryde's The Slum we see what another example had become by the First World War. Shadows fall on a once-beautiful building conjured from Pryde's childhood memories of inner-city Edinburgh. Rags hang in the windows, and an open doorway approximates the open mouth of a scream. Pryde's palette of dirty yellows evoke a smog-choked city beset by violence. Islands of people pool in the foreground, annexed from the edifice behind. Theirs is no longer a home but a shell.

By the late nineteenth century, the industrial revolution brought the need for a more modest style of residential tenement to house workers. Their homes would still bear the quintessential tenement hallmarks – solidly built with ornate ceiling cornicing, large rooms, prime locations and instantly recognisable lateral stonework as seen in Leslie Duxbury's Tenement Dwellers – but buildings were smaller than their prototypes, generally between three and five storeys high.

You'd know their colours even if their forms were scrambled, as they are in Doreen Lowe's Tenements with Figures. City fathers responsible for construction ensured each block was never taller than the width of its street, a small but thoughtful touch affording visual harmony. Tenements should play as part of the orchestra of city life, always in concordance with roads, pavements, greenery and industry.

And yet, in turn, the Victorian tenement would find itself in trouble. In Andrew Hay's A Mean Wind Wanders through the Backcourt Trash, we witness a tenement bearing signs of neglect. The building is glimpsed from behind: an intimate view visible only to those who live in the opposite tenement.

For Hay, an artist who excels at capturing the details of post-industrial hinterlands, smashed windows and smudges of litter show the truth of urban decay. The scene is timeless: it could depict the slum-like conditions found in overcrowded Gorbals tenements after the Second World War or any forgotten corner of Glasgow betrayed by council budget cuts today.

Back Court, Rotten Row, Glasgow

1955

James Morrison (1932–2020)

Gloom also seeps into James Morrison's condemned Back Court, Rotten Row, Glasgow, painted at a time when tenements were being brought into the twenty-first century. Indoor bathrooms were moved inside, families were lured out of the city into new towns and blocks were torn down.

The mood of the moment is communicated in Kelvinhaugh Street's bleak greyscale, and a similar tension can be sensed two decades later in Alasdair Gray's End of Arcadia Street (two). The title points not only to perspective but also to demolition – by 1978, Glasgow's east end was undergoing a period of radical transformation, with old buildings torn down in the hope that regeneration would solve social problems. Gray's tenement building site captures this liminal zone.

In each instance, all five artists share an approach that focuses on the tenement exterior. Facades hold up a mirror to the geopolitics of the era. Artists who venture inside, however, reveal a different world entirely. Through their eyes, the tenement interior is introspective and deeply personal.

Here, life happens and is expected: the tenement as waiting room and terminus. Lesley Banks's Leaving touches on this duality. A resident gazes out of an upper-floor window, hands hidden behind his back, shoulders slouched in resignation. In the background lie empty bookcases. To his right stands a suitcase plastered with stickers from foreign travels. A street light glares in the glass window pane; beyond that, somewhere unknown, a new experience awaits. One life is over, another is about to begin and the tenement oversees it all.

So too it goes in The 39th Week Counting, a self-portrait of Banks in the late stages of pregnancy. Her bobbed hair is enlivened by a breeze coming in through the open bay window. The suggestion of a rainbow stretches across the sky, promising hope over the jigsaw silhouette of neighbouring tenements. Indoors, on the dining table, a still life is set out with a bowl of fruit, a snuffed candle and a diary with its pages in flux.

As we see in Leaving, the average tenement resident is now just as likely to be middle class. Banks's subject is also in flux, one foot in the present, the other in the future. For the artist, the framework in which a domestic scene plays out is just as important as the scene itself.

That framework is the tenement, whose tall walls and timber floorboards are a steady reassurance in the solitude experienced by the subject of Closed Curtains. Its high ceilings offer space to think, grow and heal. Babies are born, marriages break down and the tenement is there to hold your hand throughout.

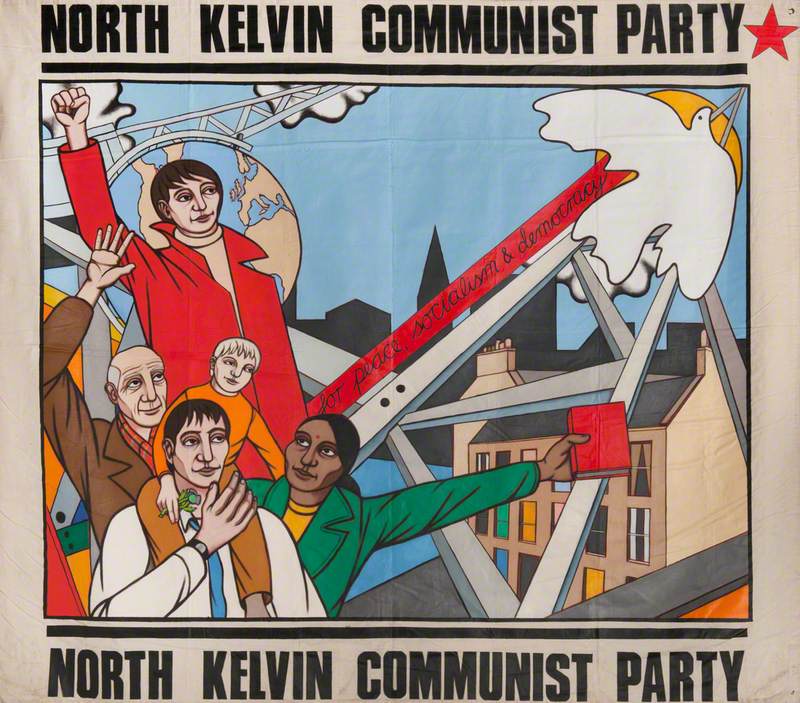

Perhaps that is why, then, the tenement is deployed as a gesture of solidarity, artistic and otherwise. It is an enduring emblem of the city, loaded with political meaning and yet at the same time a pacifying presence. Ken Currie's North Kelvin Communist Party Banner features striking primary colours, conveying ideas of hope and national identity via a white dove, thistle and blonde tenement.

Currie spoke of the need to paint in bright tones as the banner would 'be displayed high up and had to speak to people from a distance, so they had to be graphically bold'. But Currie's version of Glasgow is also representative of the kind of future of which he dreams. One of ethnic diversity and peaceful integration, an arm draped over the shoulder of a neighbour in moral support. The windows of the banner's tenement go a step further: in each hangs different styles of curtains and blinds in a rainbow of colours. Buildings can promote diversity, too.

In Currie's banner and other artist depictions of tenements, the built environment is hauled into urban conversations. In real life it is already there, impassive but never neutral. It is both landmark and anonymous, star actor and film set, friend and observer. When painters realise the tenement's relationship to its physical milieu, it starts to transcend mere stone and glass. In the end, it is just as much a citizen as any of us.

Gabriella Bennett, journalist and author

This content was supported by Creative Scotland