Stanley Cursiter was one of Scotland's finest and most prominent painters of the twentieth century. Born in Kirkwall in Orkney in 1887, Cursiter moved to Edinburgh in 1904. There he worked as an apprentice to a lithographer, before enrolling at the newly founded Edinburgh College of Art.

Although he was painting at the same time as the Scottish Colourists, Cursiter was never considered to be part of that group. Instead, he had his own distinct style, creating intense colour using rich pigment. He was a versatile artist, working in various styles, media and techniques throughout his career, and experimenting with different subjects including portraiture, landscapes and still life.

Cursiter's early works were mostly Symbolist pictures, conversation pieces and conventional lithographs. He painted watercolour landscapes of East Lothian, Orkney and Shetland, in which the light radiates from the canvas – an element of his paintings shared with the Colourists, whose work embraced the beauty of the Scottish landscape. Cursiter's Orkney roots were significant in shaping his identity and artistic inspiration.

Between the Showers, Fair Isle

c.1913

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

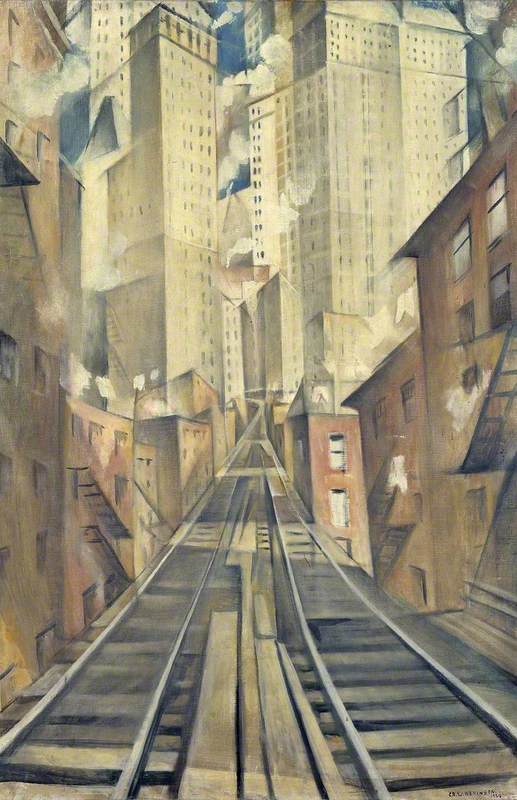

The city of Edinburgh electrified the young Orcadian painter, and inspired him to depict parts of his adopted home in a dynamic Futurist manner, with a salute to Cubism. Inspired by press photographs of Gino Severini's paintings, he created works such as Rain on Princes Street, focusing on what was then a vibrant part of Edinburgh, with shoppers jostling for space on the pavement under umbrellas.

Cursiter's artistic style and technique evolved over the years. His early works were influenced by Symbolism, Futurism and Post-Impressionism, then later he embraced Modernist tendencies. His willingness to explore different artistic approaches demonstrates his openness to the changing currents of the art world during this time.

In 1911, Cursiter saw 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists', a significant exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London, which had been organised by the painter and critic Roger Fry. While there, Cursiter met Fry and his colleague, the art critic Clive Bell, and convinced them to lend some work for exhibition in Edinburgh.

This meant that Cursiter did for Scotland what Fry had done for the rest of Britain – in 1913 he brought Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin paintings to Scotland for the first time, as part of the Society of Scottish Artists' Annual Exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy. Cursiter was later elected President of the Society, a position he held from 1918–1921.

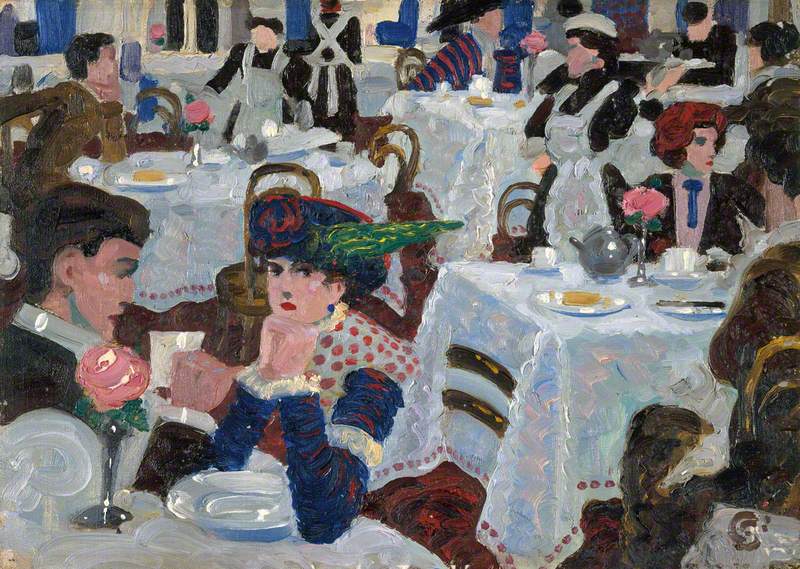

Synthesis of the Supper Room at an Arts Club Reception

1913

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

In 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, Cursiter enlisted in the 1st Battalion of the Scottish Rifles (The Cameronians) and in 1916 spent a short time at the Somme. Due to ill health, he didn't serve long at the front line.

However, the Army recognised his aptitude for drawing and his previous lithography training, and he received a commission to print maps as part of 4th Field Survey Battalion. Cursiter invented processes for map production in the field, speeding up information on enemy troop placement. He was appointed a military OBE as a result.

Lieutenant General Sir Richard George Collingwood KBE CB DSO (1903–1986)

c.1920

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

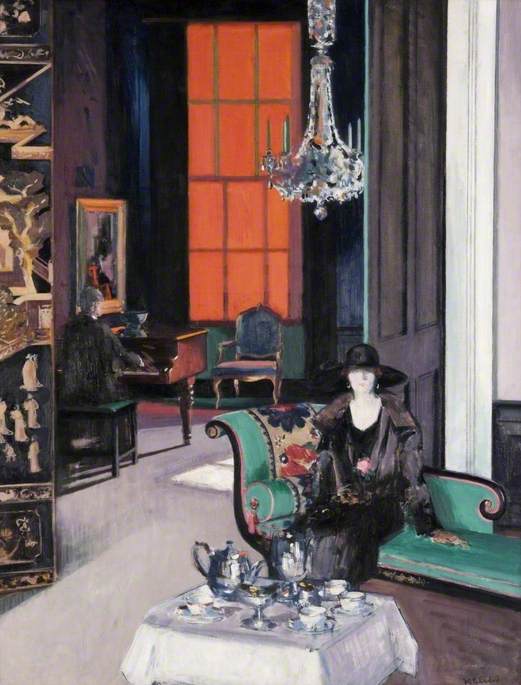

In 1914, when the country was on the brink of war, Cursiter painted Twilight, a composition set in his studio in Queen Street, Edinburgh. Here we see his early interest in large-format fashionable Edinburgh interiors, which later became a recurring motif.

Cursiter placed particular emphasis on depicting various fabrics and surfaces, the dance of light and shadow upon folds and pleats of the material showing its texture and structure realistically. Like all of his interior scenes, there is a moment captured, like a snapshot not a pose, of calm and reflection in a refined atmosphere of lyrical reverie.

Cursiter's deep interest in fashionable, high-ceilinged Edinburgh interiors and impressionistic still lifes was shared by his contemporary, the Colourist Francis Cadell. But, unlike Cadell, who concentrated on cosmetic aesthetics and surface elegance, decorating his George Street studio with the finest furniture, silk fabrics and a glossy black floor that reflected the light, Cursiter imbued his interiors with an intimate feel among the arrangements of decorative objects.

In October 1916, Cursiter married the musician Phyllis Eda Hourston, and during the 1920s they lived at 11 Royal Circus, in the heart of Edinburgh's Georgian New Town. His domestic life and partnership with Phyllis were part of his artistic journey; she was known for her contributions to the arts as well, and they shared a connection through their creative endeavours. This was the time that his painting took on a new intensity.

Cadell artfully posed models, but Cursiter's sitters were often engaged in typical domestic activities such as carrying jugs, arranging flowers, laying tables, partying or playing music. Cursiter decided to focus on these conversation pieces and, in the early 1920s, he was commissioned by the Edinburgh art dealers Aitken Dott (which later became The Scottish Gallery) to produce 20 portraits 'of pretty girls in pretty frocks, arranging flowers, leaning against a piano or gracing some similar pictorial theme'.

Cursiter used three different but very similar models: Poppy Low, Roberta Farquharson and his wife. Poppy, who had a fashionable black bob and neat features, was his favourite model.

With these paintings, we can see how the calligraphic freedom of his brushwork imitates the Spanish Old Masters such as Diego Velázquez, yet the delicate palette of whites and creams echos James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Cursiter conjured ideas from these influences but created his entirely new and original style.

His 'pretty girls in pretty frocks' paintings not only capture the beauty and grace of the women portrayed, but also provide a glimpse into the fashions and societal ideals of the time. These were not just portraits of the individual, but a dressing of both the body and the rooms.

These paintings were love letters to the enchantment found in the delicate folds of beautiful dresses, a poetic ode to the beauty that transcended the confines of the canvas and, alongside Cursiter's landscapes, they celebrated a time of peace that felt far from the recent horrors of the First World War.

In 1927 Cursiter was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, becoming a full Academician ten years later. In 1925 was appointed Keeper of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and, five years later, became Director of the National Galleries of Scotland, a role he carried out for 18 years.

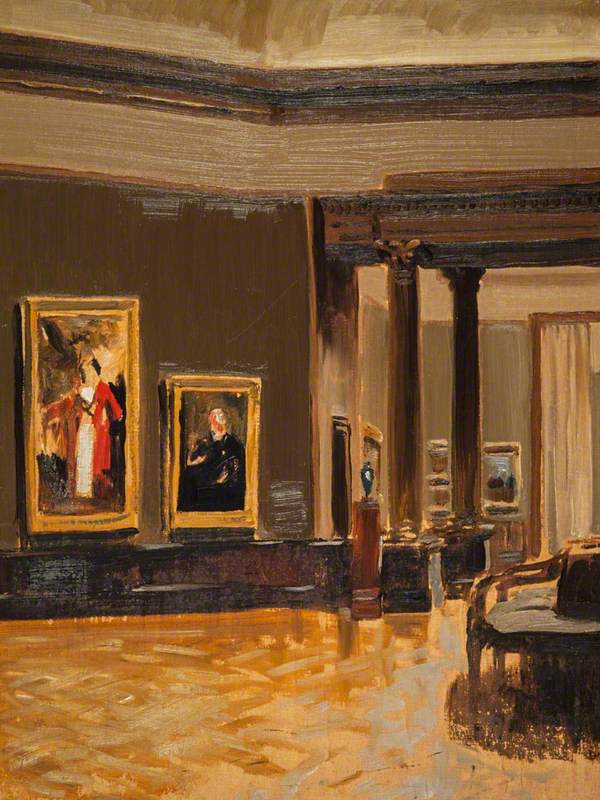

In this position, Cursiter played a crucial role in promoting contemporary Scottish art, expanding and rehanging the national collections. He also designed the gallery interior, using a series of studies to explore ideas for colour schemes. Crucially, he also lobbied tirelessly for the establishment of a national gallery of modern art in Scotland, something that was finally realised in 1959.

The Interior of the National Gallery of Scotland

c.1938

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

The Interior of the National Gallery of Scotland

c.1938

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

Cursiter resigned from the gallery in 1948 to devote more time to painting, and later that year was appointed George VI's Painter and Limner in Scotland – a role he continued until his death in 1976, latterly under Elizabeth II.

HM Queen Elizabeth II outside St Magnus Cathedral

1960

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

As well as a host of other notable appointments – including President of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolours, Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and Secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy – in 1949, Cursiter was knighted.

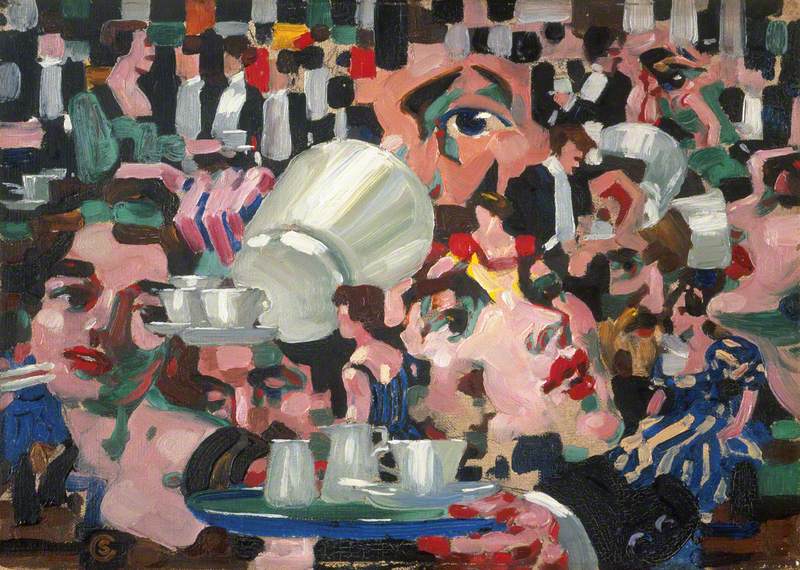

Pachmann at the Usher Hall, Edinburgh

1923

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

Stanley Cursiter's life and career spanned a period of significant cultural and artistic changes in Scotland and elsewhere, and his contributions to the arts and cultural institutions continue to be remembered and appreciated.

Outstanding features of his artwork included its vitality and sincerity, meticulous preparation and fine draftsmanship. He was also one of the few Scottish artists to experiment with the developments of Futurism to convey movement and energy.

Cursiter returned to Orkney in 1975, where he devoted himself to working on the preservation of St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall. In the 1960s he designed the interior of its St Rognvald's Chapel.

Saint Rognvald (c.1100–1158) with Saint Magnus Cathedral

1965

Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976)

After contracting bronchopneumonia, Sir Stanley Cursiter died on 22nd April 1976, in Stromness. He is buried in Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh.

Janette Ayachi, poet and freelance writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland