(b Aix-en-Provence, 19 Jan. 1839; d Aix-en-Provence, 23 Oct. 1906). French painter, with Gauguin and van Gogh the greatest of the Post-Impressionists and a key influence on the development of 20th-century art. He was the son of a prosperous hat manufacturer who was also part-owner of a bank in Aix-en-Provence. In 1861 he abandoned the study of law, and his father reluctantly gave him permission (and a modest allowance) to train as an artist in Paris. He studied at the Académie Suisse, where he met Camille Pissarro, but after a few months he went back to Aix discouraged (he was a touchy character who hid his insecurities by posing as a provincial boor, once refusing to shake hands with the elegant Manet because he claimed he had not washed for days and did not wish to dirty the great man).

Read more

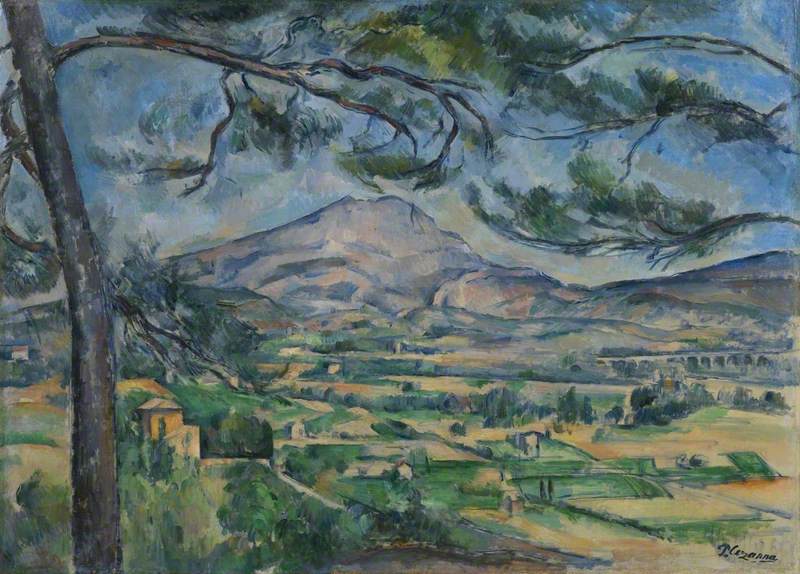

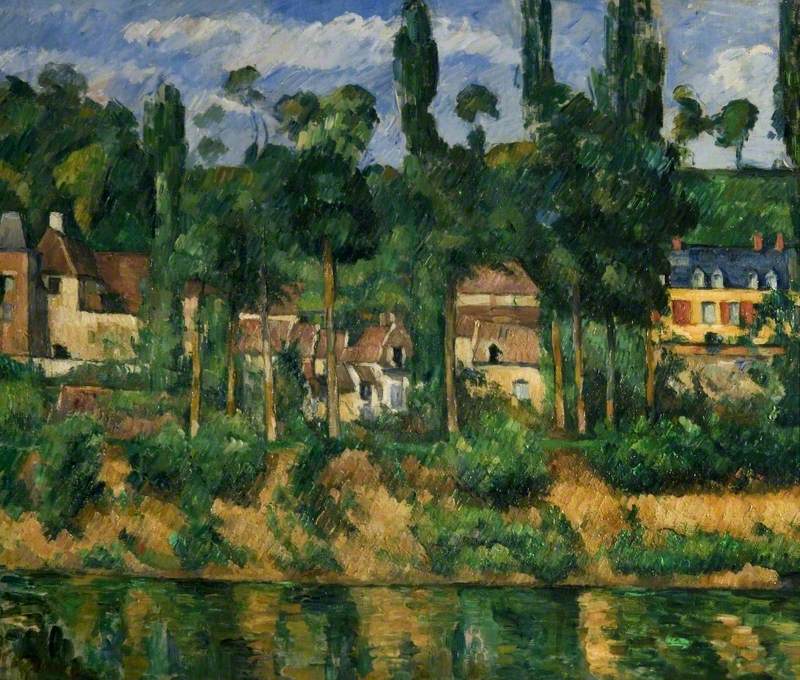

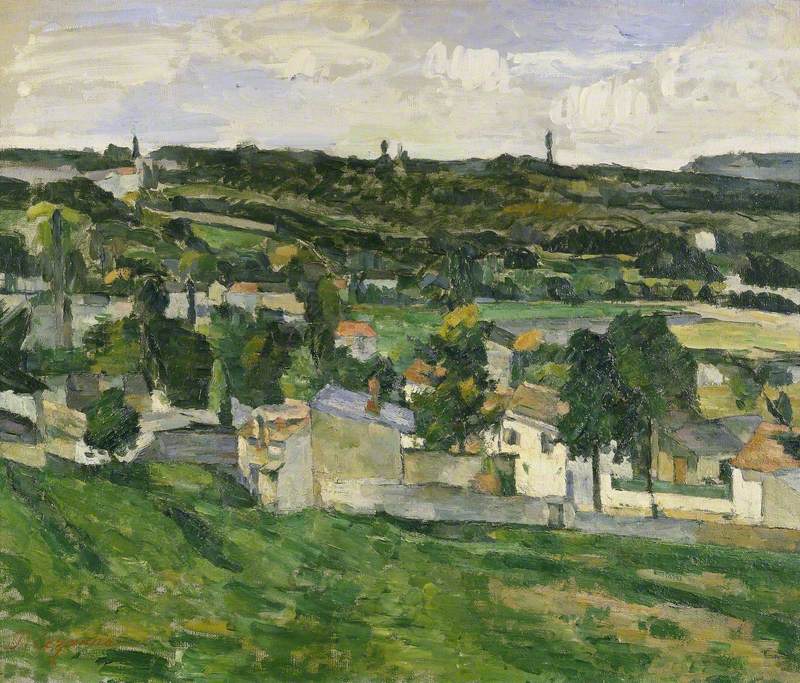

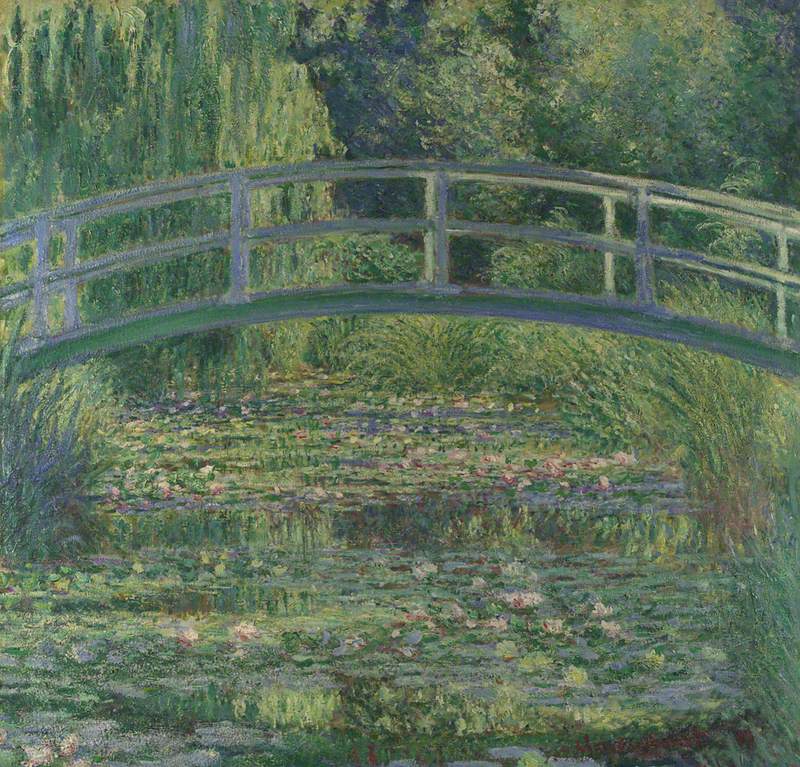

The following year he resumed his studies in Paris and in 1863 he exhibited at the Salon des Refusés (his attempts to get his work accepted for the official Salon regularly ended in failure). At this time Cézanne's work consisted mainly of portraits and imaginative figure subjects, with occasional still lifes. The portraits—mostly of members of his family (including self-portraits)—are sombre, using thick, slab-like paint, often applied with a palette knife. The imaginative subjects are very different, their subjects typically being erotic or violent and the handling of paint impetuous (The Murder, c.1868, Walker AG, Liverpool). They show Cézanne's admiration for Delacroix (of whose pictures he made several copies), but they have none of Delacroix's sophistication. Compared with Delacroix's work, indeed, they look brutally crude, and even with the benefit of hindsight it is hard to see the seeds of Cézanne's future greatness in them. In 1869 he met Hortense Fiquet, a model and seamstress, who became his mistress and bore him a son, Paul, in 1872. Cézanne initially managed to keep them a secret from his family in Aix—he was terrified of his domineering father—but the truth was discovered in 1878 and he eventually married Hortense in 1886, shortly before the death of his father (who had at last become reconciled to the relationship). After the birth of his son, Cézanne could no longer afford to live in Paris, so he moved to Pontoise, about 30 km (20 miles) to the north-west, joining his friend Pissarro, who had recently settled there. The following year, 1873, he moved to nearby Auvers-sur-Oise, then in 1874 returned to Paris. Although this rural interlude was fairly brief, it was highly important in Cézanne's development, for under Pissarro's influence he took up landscape painting seriously, and the close study of nature this involved led him to move away from the imaginative subjects of his youth and concentrate instead on the real world around him. In line with this change of subject, he abandoned the gloomy tonality of his early work and discovered the joys of light and colour, as his style came under the influence of Impressionism (House of the Hanged Man, 1873, Mus. d'Orsay, Paris). He exhibited at the first (1874) and third (1877) Impressionist exhibitions (his work was critically savaged on both occasions), but he always stood somewhat apart from the group and never wholly adopted their aims and techniques. He was interested in structural analysis rather than in surface effects, and his objective was to combine the formal grandeur of the Old Masters with the naturalism and colour of the best contemporary painting. His aims were summed up in two celebrated remarks: that it was his ambition ‘to do Poussin again, from Nature’, and that he wanted to make of Impressionism ‘something solid and enduring, like the art of the museums’.After the death of his father in 1886, Cézanne inherited the family estate (the Jas de Bouffan, which features in many of his paintings), and lived mainly in Aix (he often visited Paris, but otherwise travelled little, only once going abroad in his whole life, to Switzerland in 1890). He was now free of financial worries for the first time in his career and able to concentrate entirely on his art; in the remaining twenty years of his life he did little else but paint—pursuing his ideals with extraordinary patience and self-discipline. He devoted himself principally to certain favourite themes—portraits of his wife, still lifes, and above all the landscape of Provence, particularly the Mont Ste Victoire, which came to have something of the same emotional significance for him that Mount Fuji has for Japanese artists. His painstaking analysis of nature differed fundamentally from Monet's exercises in painting repeated views of subjects such as Haystacks or Poplars. Monet's ideal was to finish a landscape painting in only one session of work so that it captured the feeling of a particular moment, whereas Cézanne returned to the same place again and again to create a deeply pondered image that presented his accumulated vision of the subject: his pictures rarely give any obvious indication of the time of day or even the season represented. He worked slowly and intuitively, creating a sense of depth and solidity not through conventional draughtsmanship and perspective, but through extremely delicate variations of tone, and he distorted natural appearances—subtly tilting and stretching forms—to achieve the pictorial balance that was his central concern. In his final years he created works of luminous beauty and classical dignity that are a world away from the wild, impulsive pictures of his youth. The culminating paintings of his career include three large pictures of Bathers (female nudes in a landscape setting) that are among his most majestic creations; one of them, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was perhaps entirely painted in 1906, the year of his death.Cézanne had worked in comparative obscurity until he was given a one-man show in Paris by Ambroise Vollard in 1895. It made little impact on the public but excited many younger artists, and because Cézanne himself was rarely seen he began to acquire a legendary reputation. By the end of the century he was revered as the ‘Sage’ by many of the avant-garde and in 1904 the Salon d'Automne devoted a special exhibition to him. A memorial exhibition of his work at the same venue in 1907 was a major factor in the genesis of Cubism, and his subsequent influence has been profound, varied, and enduring, earning him the title ‘the father of modern art’: the belief that the picture surface has an integrity of its own irrespective of what it represents—a characteristic of so much modern painting—stems largely from him. It is not only the quality of his work that has proved an inspiration, but also the example he set of complete devotion to art: Henri Matisse bought a picture by Cézanne in 1899 and in 1936 wrote that ‘It has sustained me spiritually in the critical moments of my career as an artist; from it I have drawn my faith and perseverance.’Cézanne often worked on pictures over a long period—he is said to have had over 100 sittings for a portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1899, Petit Palais, Paris) before abandoning it with the comment that he was not displeased with the shirt front. In spite of this laborious slowness, he left a substantial body of work, including drawings and watercolours as well as oils. He ranks amongst the greatest of all exponents of watercolour, using the medium with extraordinary subtlety and delicacy, often leaving large areas of the paper blank and combining ethereal touches of colour with faint pencil lines. There are examples of his work in many major museums, with particularly fine collections in, for instance, the Courtauld Gallery, London; the Musée d'Orsay, Paris; and the Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania. His studio in Aix is now a Cézanne museum, reconstructed as it was at the time of his death and displaying personal mementoes such as his hat and clay pipe. See also zola.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)