In this series, 'Conservation in focus', Simon Gillespie, Director of Simon Gillespie Studio, explores the art of conservation. In each article, Simon looks in depth at a particular technique or tool that is crucial to conservators and explores the challenges – and triumphs – associated with their everyday work.

Analysing paint can yield a wealth of information: for example, by finding out what specific pigments the artist has used, we can sometimes narrow down the date of the painting. That's not the case with all pigments, however: many have been available to artists for thousands of years, such as red ochre.

In the case of the Olivia Boteler Porter portrait which we restored for The Bowes Museum (some time before Britain's Lost Masterpieces was born), the results of the analysis told us that the pigments were all consistent with a painting from Anthony van Dyck's era, although they couldn't prove that it was done by him specifically and not by another artist working at the same time or later.

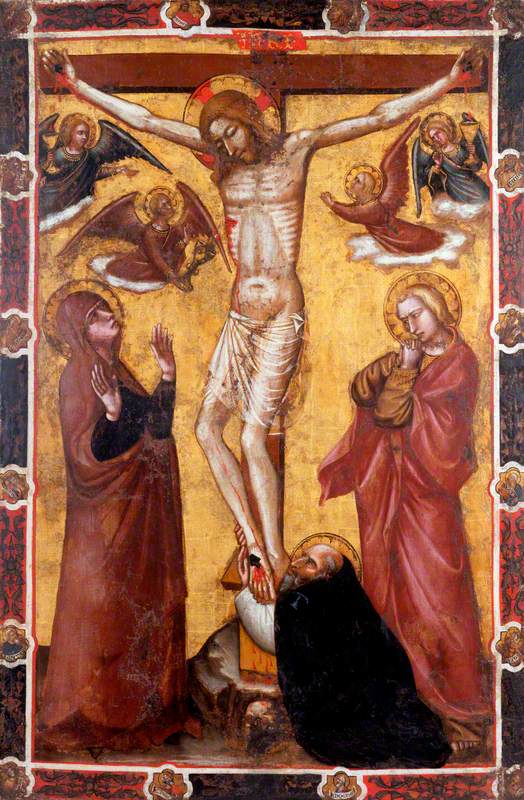

Annotated sample map of the Botticelli, with paint samples ready to be analysed by the lab

Other pigments were only discovered or invented recently: if, on analysing the blue paint in an artwork, you find it to be Prussian blue, then you know that the painting must have been painted in or after 1724, the date when Prussian blue became available to artists. Cadmium red was only available from 1919.

The Confluence of the Thames and the Medway

exhibited 1808

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Turner was famously very interested in the new pigments being developed during his career and used them as they became available, sometimes totally replacing older pigments where he deemed them deficient: for example, from 1807 he stopped using smalt blue in favour of cobalt blue.

Paint analysis can be very helpful when trying to date a painting, or even just to show that it is possible for the painting to have been done during the lifetime of a particular artist. So far, we have been fortunate on the Britain's Lost Masterpieces series that none of our candidates for lost Old Masters have turned out to contain cadmium red or another modern pigment in the original paint layer!

Self Portrait at the Age of 22

c.1623–c.1629

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (studio of)

In the case of the Knightshayes Rembrandt, the layer of paint in the background (which under the microscope could be seen to extend over old damages) was shown to contain barium white, which was only discovered in the nineteenth century, confirming that this layer was a later addition. This was further supported by the fact that that layer of paint covered damages that had occurred after the picture was completed.

Another interesting aspect of this painting was that Rembrandt's studio practice was to apply a ground layer, which was made up of a base layer of chalk covered with a mixture of lead white paint and a brown earth pigment. It was very pleasing that this is precisely what was found on the self-portrait, as it served as supporting evidence that the picture was not a later copy but had been at least painted in Rembrandt's studio – perhaps by the master himself.

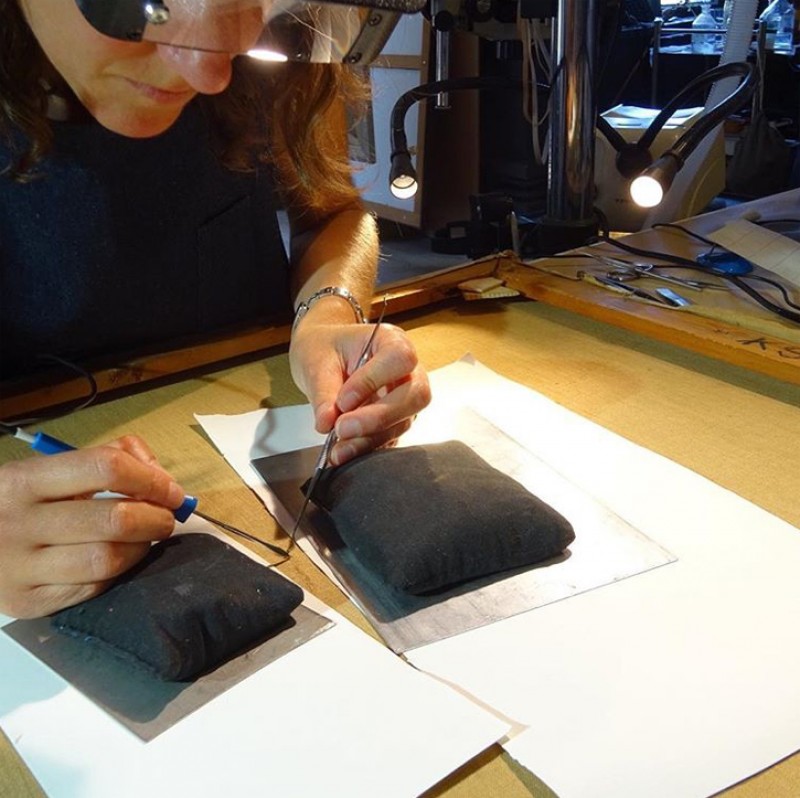

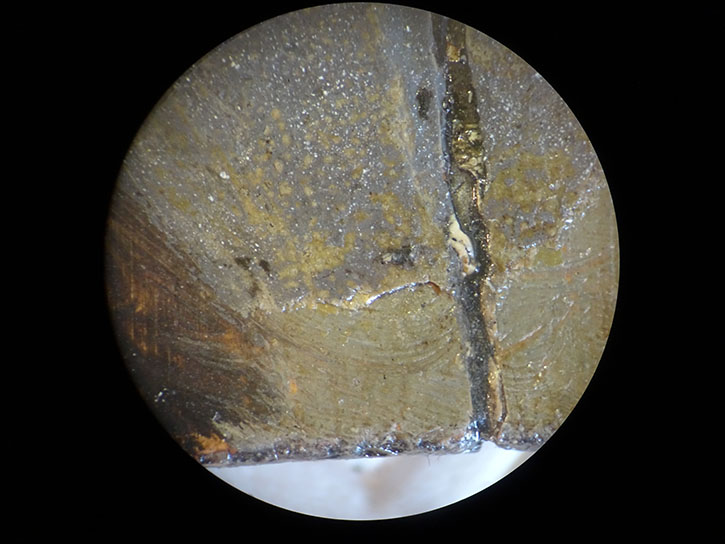

The Knightshayes Rembrandt seen under the microscope, showing overpaint going over damages

Another type of paint analysis is looking not at a singular pigment but at the cross-section of a painting to see the layers that make up a painting, just as an archaeologist might dig a site in Britain going downwards from the current soil layer down to the Victorian period, Medieval period, Roman period, Iron Age and so on. A cross-section would show, from the bottom up, the ground layer, paint layers in the order in which they were applied, any varnish layers and any dirt layers. You might find a dirt layer between two layers of varnish, which would tell you that there had been a gap of time between the two varnish layers being applied. You might also see later paint layers sitting on top of the varnish layer.

A diagram showing an example of paint layer structure with a close-up photograph

With the Autumn panel – by De Momper and the workshop of Brueghel the elder – we were able to see, on top of the layer of original paint, evidence of multiple layers of dirt, yellow varnish and overpaint.

Some pigments change colour over time as they are exposed to oxygen in the air, and so doing paint analysis can give us an idea of what the original paint colour would have been when the artist first applied it.

For example, the coat in the portrait by Antonius Mor is now brown but, by analysing the pigments, we know that the coat would originally have been blue: it is painted with smalt blue pigment, which has faded. As a result, the effect of the portrait now is much less vibrant than it would have been originally… but it is still a hugely powerful picture thanks to the amazing psychological intensity of the sitter's face.

A cross-section of the Antonius Mor painting, showing evidence of smalt

So much for all the ways of looking at a painting to understand its makeup. What does the treatment itself involve? I'll begin exploring this in the next article.

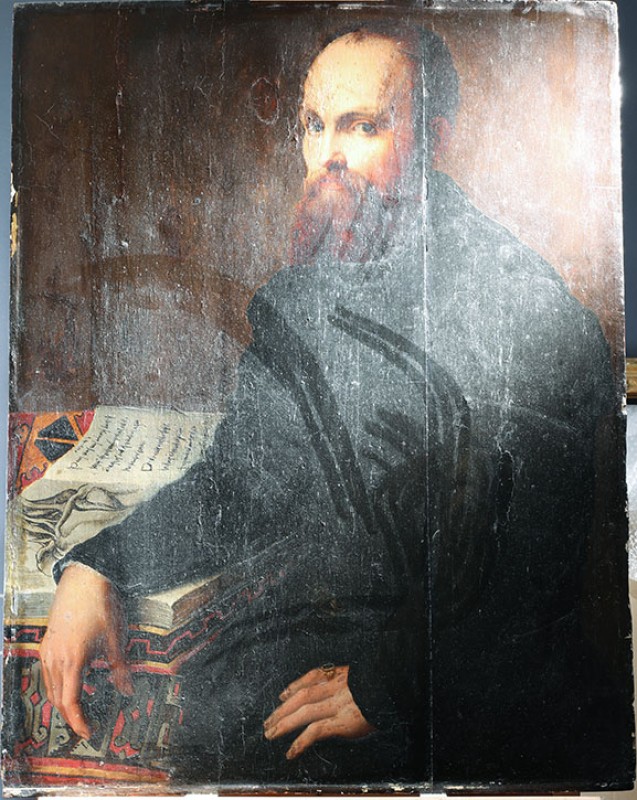

Simon Gillespie, Director at Simon Gillespie Studio

Previous: Using x-ray and infrared images