The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her Last Berth to be broken up, 1838 1839

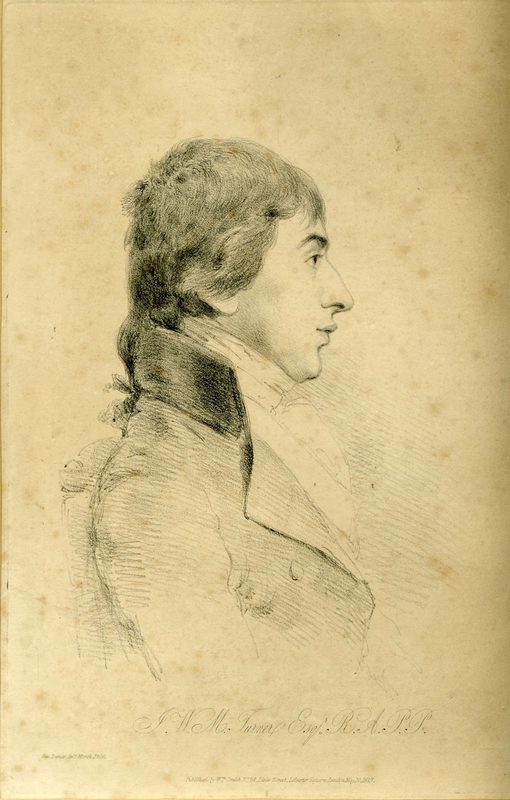

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

The National Gallery, London

Joseph Mallord William Turner, known as J. M. W. Turner (Born London, 23 April 1775; died Chelsea, Middlesex [now in London], 19 December 1851). English painter, one of the greatest figures in the history of landscape painting. His family called him Bill or William, but he is now invariably known as J. M. W. Turner (which is how he usually signed his pictures). He showed a talent for drawing from an early age and as a boy earned money by colouring prints. In 1789 he began working as a draughtsman for the architect Thomas Hardwick, and later in the same year he enrolled at the Royal Academy Schools, where he studied regularly until 1793 and intermittently until 1799. Early in his student days he also had lessons from Thomas Malton (1748–1804), a topographical watercolourist who specialized in neat and detailed town views and whom he later described as ‘my real master’.

From early in his career Turner was aware of his place in the tradition of landscape painting and he often produced works in homage to (or rivalry with) his great predecessors such as Claude (whom he particularly revered) and Willem van de Velde the Younger. However, he soon began to paint more original pictures in which he depicted the violence of nature in powerful Romantic fashion. The Shipwreck (1805, Tate) was one of his first works in this vein, and one of the most celebrated is Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812, Tate), of which a contemporary newspaper (the Examiner) wrote: ‘This is a performance that classes Mr Turner in the highest rank of landscape painters…the moral and physical elements are here in powerful unison blended by a most masterly hand, awakening emotions of awe and grandeur.’ During these years, however, he continued exhibiting more conventional pictures and still earned a good deal of his large income through work for engravers. His most ambitious engraving project was his Liber Studiorum (Book of Studies), conceived in emulation of Claude's Liber Veritatis and intended to show the range of his own work; between 1807 and 1819 he issued 71 of a projected 100 plates.

Turner made his first journey to the Continent in 1802, during a temporary peace in the war with France, visiting Paris like so many other artists to see pictures looted by Napoleon, which were then on exhibition. From Paris he travelled on to Switzerland. The resumption of war made Continental travel impossible for more than a decade, and Turner did not go abroad again until 1817, when he visited Belgium, Holland, and the Rhine. He first visited Italy two years later, and from then until 1845 made fairly regular journeys abroad (including three more to Italy, the last in 1840). Unlike his contemporary Constable, who concentrated on painting the places he knew best, Turner was inspired to a great extent by what he saw on his travels (he lived in London all his life, but the city appears fairly infrequently in his paintings). The mountains and lakes of Switzerland and the haunting beauty of Venice, in particular, provided him with an enduring fund of subjects. He was inspired by history (especially ancient history) and literature as well as nature. Many of the paintings he exhibited at the Royal Academy were accompanied by verses printed in the catalogue, and from 1800 he added lines of poetry he had composed himself.

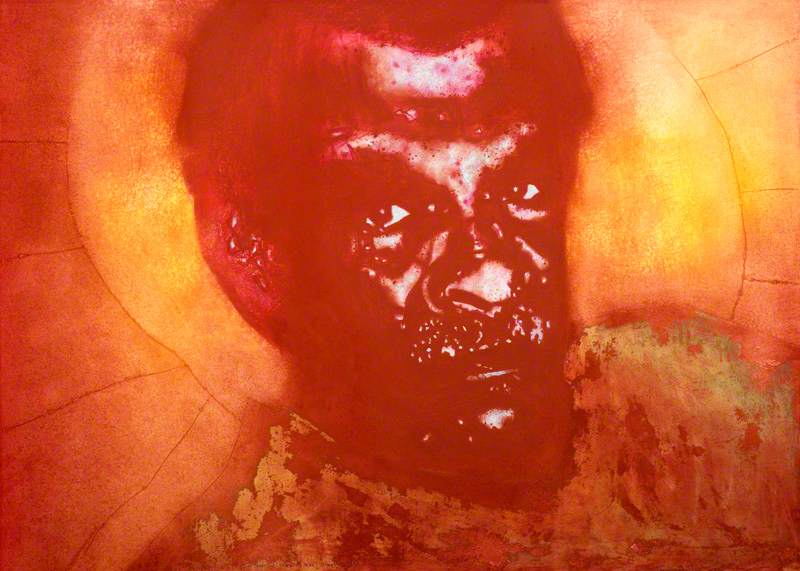

From the 1830s Turner's painting became increasingly personal and free, with detail subordinated to general effects of colour and light. To many critics it was incomprehensible, and one of his most famous pictures—Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842, Tate)—is said to have been dismissed as ‘soapsuds and whitewash’. Turner's wealth and status allowed him to remain indifferent to such attacks, and he continued to have many admirers, including some who regarded him as the outstanding genius of the day. His most important patron was the 3rd Earl of Egremont (1751–1837), who was unusual among collectors of the time in buying contemporary British art (sculpture as well as painting) on a large scale. Turner had a studio at Petworth, Egremont's country house in Sussex, and several of his paintings are still to be seen there (although their ownership was transferred to the Tate Gallery in 1984). Turner's other great champion was the young Ruskin, who first met him in 1840 and wrote eloquently of him in the first volume of Modern Painters, published in 1843. By this time some of Turner's compositions were almost abstract, the forms dissolved in a haze of light and colour, the paint so delicate it appears almost to have been floated onto the canvas: ‘He seems to paint with tinted steam, so evanescent and so airy’, wrote Constable. Turner's originality lay not only in such handling of colour and light, but also in his use of the power, beauty, and mystery of nature to express deep human concerns. For example, The Fighting Temeraire (1839, NG, London), showing a ship that had fought at Trafalgar being towed to the breaker's yard, is not just a beautiful marine scene, but also a poignant elegy for a passing era.

For many years Turner was a prominent figure at the Royal Academy (he was professor of perspective 1807–38 and in 1845–6 he took over the president's duties when Sir Martin Archer Shee was ill). However, he always carefully guarded his private life and in his later years he became more and more of a recluse, sometimes calling himself Mr Booth (assuming the name of his mistress Sophia Booth; he never married but had two long-term relationships, both with widows, and is rumoured to have fathered several children). After his death, Ruskin (his executor) destroyed many erotic drawings that he found among his works, thinking that they tainted his hero's memory.

In his will Turner left plans for disposing of his fortune (he wanted to found an almshouse for ‘poor and decayed male artists’) and for the creation of a special gallery at the National Gallery to display certain of his paintings (he had a huge stock of his work, including not only pictures that had never been sold, but also favourite paintings that he had bought back at auction). However, the will was contested by long-forgotten cousins (one of whom had a lawyer son with the splendidly Dickensian name of Jabez Tepper), and they won Turner's money in 1856; at the same time the Court of Chancery awarded all the works remaining in his possession at his death to the National Gallery—about 300 oils and 19,000 works on paper. Most of these are now in the Clore Gallery at Tate Britain, but a few of Turner's most famous oils remain in the National Gallery.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)