When the great Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569) died at the height of his powers, he was not to know that he would be the foremost of a dynasty of painters.

In the artistic output of his two sons, it is tempting to read an archetypal story of filial loyalty and rebellion. Pieter the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638) – the older son – created copy after copy of his father's paintings, while Jan (1568–1625) took a very different path, his work diversifying during and after a stay in Italy.

Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery

1565

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Sons of one of art's greatest figures – Pieter the elder was acclaimed soon after his death as 'the most perfect painter of his age' – the sons reinstated the 'h' in their name (dropped by Pieter the elder around 1559) to become Breughels. This was a gesture of both independence and humility, declaring themselves to be artists in their own right, but not to be confused with their esteemed father.

Winter Landscape with Bird Trap

1565, oil on wood panel by Pieter Bruegel the elder (1525–1569)

Pieter the younger made copies of his father's works on an industrial scale – as many as 45 copies of Winter Landscape with Bird Trap have been personally attributed to him – and 127 versions are known to exist. Although making copies of artworks was quite common at that time, and certainly not frowned upon, Pieter the younger's production has been described by Bruegel specialist Christina Currie as a unique 'phenomenon of artistic mimicry pushed to the extreme'.

The Bird Trap (Winter Landscape)

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638)

The commercial appeal of this activity is obvious, and resulted in copies (and copies of copies) that were very variable in quality. Pieter the younger was clearly a talented maker of replicas, but it is thought that the less accomplished versions were made by his workshop or subcontracted to other artists, with Pieter overseeing the process.

The Massacre of the Innocents

(after Pieter Bruegel the elder)

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638)

To a far lesser extent than his brother, Jan also based paintings on his father's works. Quite how the Brueghel boys were able to make their copies and adaptations is interesting in itself. Their father died when they were infants, and they would not have had access to their father's original paintings, which were dispersed around Europe in private collections. It is thought that they possessed preparatory drawings, or cartoons, handed down to them, and that these drawings even contained descriptions of the paintings' colours.

As highly skilled artists, Pieter and Jan brought their father's works to a wider public, and scholars believe they give access through their versions to some of Pieter the elder's lost masterpieces.

Two Peasants Binding Faggots

c.1620

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638)

Although no 'original' of Pieter the younger's Two Peasants Binding Faggots is known, the man cutting willow wands in the background reminds us of a very similar figure in Pieter the elder's Gloomy Day.

Gloomy Day (Early Spring)

1565, oil on wood by Pieter Bruegel the elder (1525–1569)

The stout man on the left resembles well-fed peasants in Pieter the elder's works, and his pairing with the thin man recalls the morality tales illustrated by Pieter the elder's engravings The Fat Kitchen and its counterpart The Thin Kitchen. But we cannot be sure that there was an original of this image by Pieter the elder. Perhaps Two Peasants Binding Faggots is a work of Pieter the younger's own conception, a pastiche which drew on popular Bruegelian characters.

The Fat Kitchen

1563, engraving by Pieter van der Heyden (c. 1525–1569) after Pieter Bruegel the elder (1525–1569)

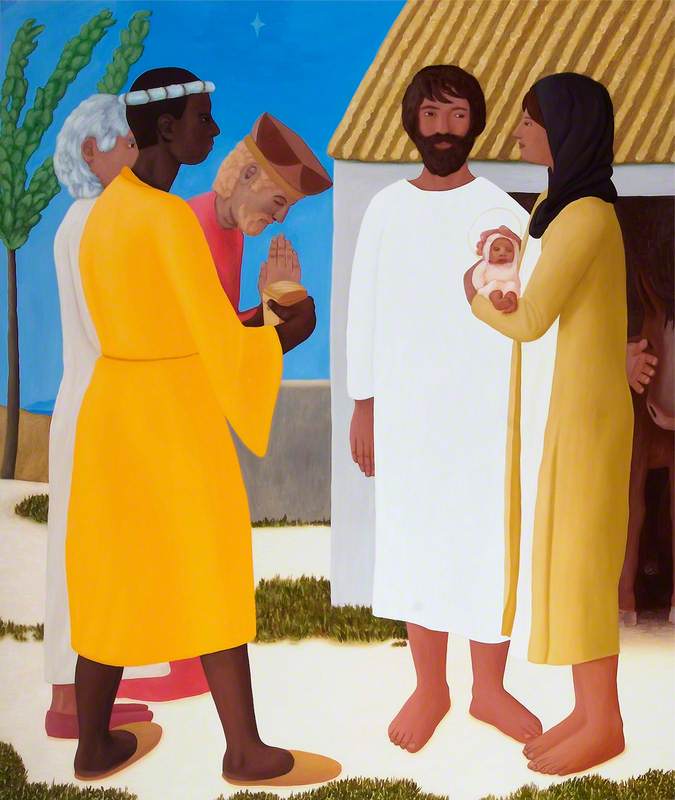

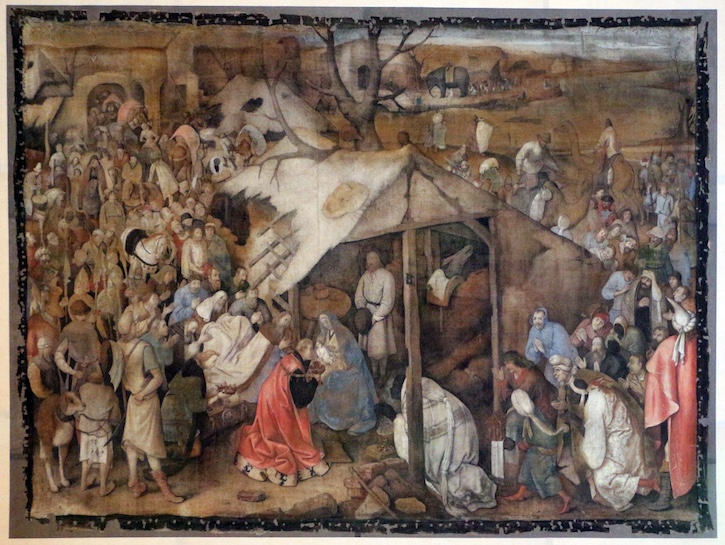

Pieter the elder's The Adoration of the Kings provides a close-up view of the Holy Family and the three kings offering their gifts. The Christ Child, who recoils from the kneeling king, is hemmed in by staring adults, giving the scene an unsettling atmosphere.

The Brueghel sons chose a quite different viewpoint for their depictions of this Biblical episode. In Jan's picture, we have withdrawn to a distant position, revealing a multitude of onlookers and the town beyond. Taken from Pieter the elder's painting, we find the tall soldier with his halberd in his place before the stable, and Joseph in his old pose behind Mary, his hat held at his midriff, turning to hear what is being whispered in his ear.

The composition and the dilapidated stable, however, come from Hieronymus Bosch's Adoration in the Prado, Madrid. And from the Bosch, Jan takes the important-looking turbaned figure peering round the door frame.

Pieter the younger's version of the scene has much in common with his brother's, but it lacks the ingredients from his father's Adoration. It very closely resembles a version in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, which that museum claims to be by Pieter the elder, although this is disputed.

Adoration of the Magi

c.1556, tempera on canvas by Pieter Bruegel the elder (1525–1569)

One of Pieter the elder's most famous works, The Procession to Calvary (below), receives a notably altered treatment by Pieter the younger.

The Procession to Calvary

1602

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638)

Pieter the younger's The Procession to Calvary keeps certain important elements of Pieter the elder's painting – the curving, motley parade heading to Golgotha at the top right of the picture, the distraught Mary and her companions in the right foreground – but there are some interesting differences, notably the prominence of the figure of Christ, brought to the foreground of the painting, where in Pieter the elder's original he is a tiny detail lost in the middle of the crowd.

The Procession to Calvary

1564, oil on wood by Pieter Bruegel the elder (1525–1569)

The effect of this is heightened by the wide, open panorama in Pieter the elder's image, across which are scattered the moving indifferent onlookers. In Pieter the younger's work, the nearby town intrudes significantly from the left, which seems to push Christ, and the figures around him, to the front of the scene.

This is more than a compositional variation on a theme. Pieter the elder's art is characterised by the subversion of standard religious imagery. Demoting Christ to a barely visible detail was a bold and arguably polemical move. His son, we might well assume, seemed less comfortable with this treatment, and put Christ in his expected place – prominently before us – even if the populated landscape retains its overall dominance.

With the exception of a few works that recall his father's compositions, Jan Brueghel the elder's art could hardly be more different. Consider the opulent Nature and Her Followers. This is one of many collaborations that Jan undertook, here with his friend Peter Paul Rubens.

Nature and Her Followers

c.1615

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Jan Brueghel the elder (1568–1625)

Playing to their strengths, Rubens did the nudes, while Jan did the garlands. Such a painting would be inconceivable as a work of Pieter the elder, in which myth and nudity are scarce. Bruegel's concerns were the earthly and everyday. His people wear over their unbeautiful bodies the heavy clothes of the peasantry. Angels and heavenly light are absent.

An instructive comparison is found in the treatment of the story of the Flight into Egypt from Matthew 2:13–15. In collaboration with Hans Rottenhammer I, Jan produced a series of bucolic paintings of the Holy Family resting on the long journey from Judea to Egypt.

In the example above, the mood is relaxed and ethereal. Angels amuse Mary and Jesus against a backdrop of blooms and feathery foliage. There is little to suggest the hardships of a long journey or the threat that caused them to flee. The scene is pleasant but fantastical.

Pieter the elder's chosen treatment of the episode is of the Flight rather than the Rest. Bruegel presents the Holy Family as diminutive figures against a vast panorama. The challenges of the journey are evident in the craggy landscape yet to be negotiated. Mary and Joseph are deliberately marginalised: modest figures facing the hardships of the real world in all its forbidding majesty.

Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

1563

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

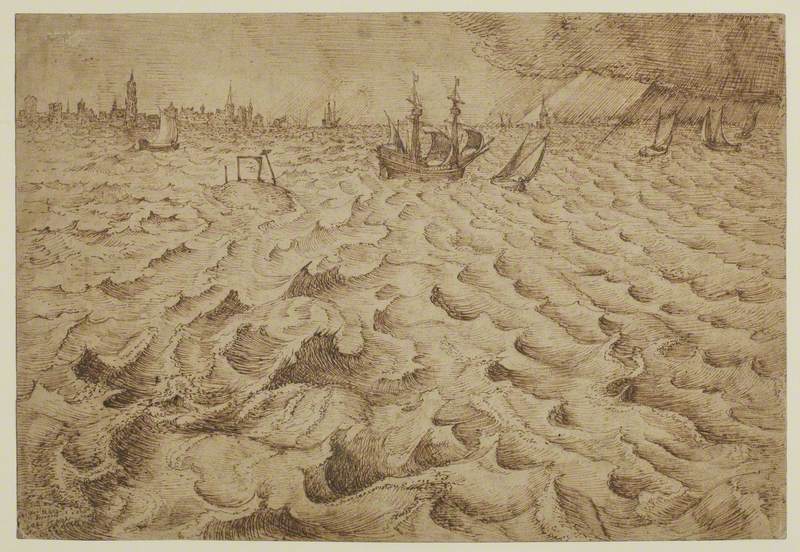

In his early 20s, Jan Brueghel travelled to Italy, where he stayed for six years. Unlike his father, who spent three years there and was hardly influenced by the art of the south, Jan's travels seem to have encouraged him to develop styles and subjects quite different from his father's – and by extension, his brother's.

In Italy he made landscapes and flower paintings for a patron, Cardinal Federico Borromeo, subjects he continued to paint following his return to Antwerp in 1596. Works such as A Stoneware Vase of Flowers fed an appetite, growing at the time in the Netherlands, for exotic blooms. The flowers themselves entered the port of Antwerp from faraway places and were cultivated in private gardens. Such paintings brought Jan considerable wealth and esteem. It was a genre – still life – that his father never practised.

The flowers in Jan's paintings were meticulously observed but their arrangements are, in fact, impossible: specimens in full bloom were grouped together even though they flowered at different times of the year. This incongruity extended to Jan's paintings of animals. As with plants, strange and exotic animals arrived through the port of Antwerp, to be kept in menageries. Jan portrayed them with great accuracy but in unnatural proximity to each other, in scenes such as The Garden of Eden with the Temptation in the Background.

The Garden of Eden with the Temptation in the Background

c.1600

Jan Brueghel the elder (1568–1625)

There is obvious tension among the animals thrust together in a crowded glade. This is not the harmonious Eden we might expect, but then the grave matter of the Fall of Man is being enacted in the distance. Look carefully, and we can see Eve tempting Adam with the apple. Their presence as a detail, withdrawn into the middle distance, is reminiscent of the works of Pieter the elder: the important actors are removed from centre stage.

The Bruegel dynasty did not end with Pieter and Jan. Each had their own artistic offspring, Jan being the most productive in this respect. Jan's eldest son, Jan Brueghel the younger (1601–1678), assumed the role of copyist of his father's works, and produced more flower paintings to satisfy an eager market, while one of his sons, Abraham Brueghel (c.1631–1690), further developed the art of flower painting.

The transition from Jan the elder's rather emblematic and scholarly style, in which each bloom is presented faithfully as if in a botanical illustration, loosened with the more naturalistic compositions of his son Jan, in which the arrangements flop and spill out of the wicker basket, and ultimately led to the more impressionistic depictions of Abraham, with their play of light and shade, as well as concern for perspective.

The mania for flowers in the Netherlands, tulips in particular, which developed in the early seventeenth century, forced its way into artists' works even when the flowers themselves were not the main subject.

An Allegory of Abundance

c.1631/1632

Hendrik van Balen I (1575–1632) and Jan Brueghel the younger (1601–1678)

They add to the surfeit of Nature in An Allegory of Abundance, a collaboration between Jan Brueghel the younger and Hendrik van Balen I. In its lack of idealised classical imagery, as well as of irony or a moralising message, this painting is a far cry from old Pieter Bruegel.

One last artist, however, brings us back to the province of that 'most perfect painter of his age'. The husband of Jan Brueghel the elder's daughter Anna, David Teniers II (1610–1690) was a prolific painter of genre pictures. These scenes from everyday life find the humble preoccupations of ordinary people a fit subject for art, much as the peerless Pieter Bruegel did, with the welcome return, some would say, of humour and the exposure of human folly.

Adam Wattam, writer

'Brueghel: The Family Reunion' is at the Het Noordbrabants Museum, Netherlands, from 30th September 2023 to 7th January 2024

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, The Brueg[H]el Phenomenon, Brepols, 2012

Amy Orrock, Bruegel: Defining a Dynasty, Philip Wilson, 2017

Larry Silver, Pieter Bruegel, Abbeville, 2011

Robert Wenley (ed.), Peasants and Proverbs: Pieter Brueghel the Younger as Moralist and Entrepreneur, Paul Holberton, 2022

.jpg)