(b ?'s-Hertogenbosch, c.1450; bur. 's-Hertogenbosch, 9 Aug. 1516). Netherlandish painter, active for all his known career in 's-Hertogenbosch, where he is first documented in 1474. His real name was Jerome van Aken (perhaps indicating family origins in Aachen, Germany), but on the few pictures that he signed he used the name by which he has become famous: ‘Hieronymus’ (or ‘Jheronimus’ as he spelt it) is the Latin form of Jerome, and ‘Bosch’ is a shortened version of the name of his town. Although it was fairly remote from the major art centres of the Netherlands, it was one of the most prosperous towns in the Duchy of Brabant, with a vigorous cultural and intellectual life. Bosch, who came from a long line of artists, was the leading painter of the day there, although he was married to a wealthy woman and probably had no need to paint for a living.

Read more

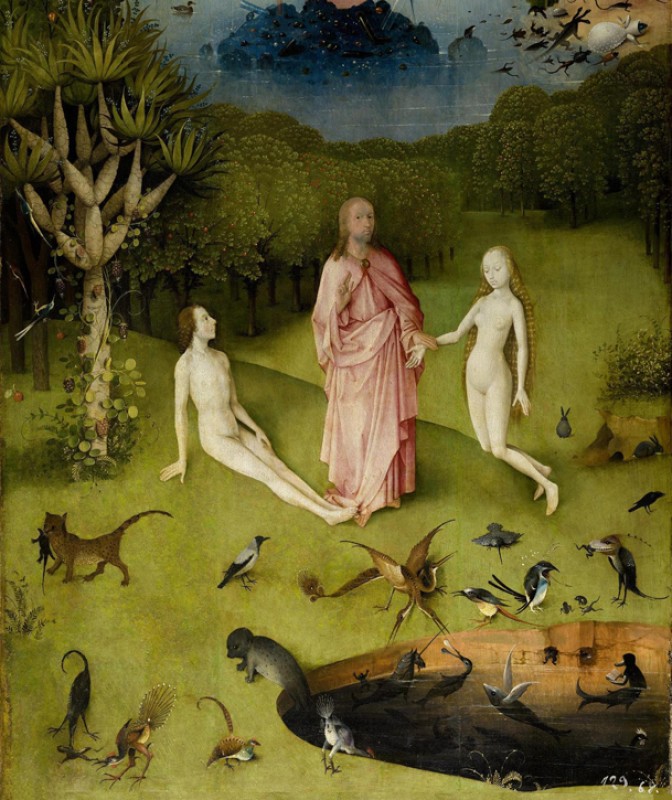

He was a prominent member of a local religious organization, the Brotherhood of our Lady, but because his most characteristic paintings seem so bizarre to modern eyes, his work has inspired theories that he was involved in heresy, witchcraft, or various esoteric practices. However, all the contemporary evidence indicates that he held the orthodox religious views of his time and was a respected member of his community. It was evidently not until after his death that it was first suggested he had embodied unorthodox beliefs in his work, and it was not until the 20th century that speculation (sometimes wild speculation) about his character and motivation began in earnest. There is much about his art that is obscure and perplexing, but modern research has helped to show how his work is a reflection of the cultural traditions of his time rather than the expression of eccentric private concerns.About 40 surviving paintings are generally regarded as autograph works by Bosch, but none is dated and it has proved difficult to construct a satisfactory chronology. More than half of these pictures are on traditional Christian subjects (Crucifixion, c.1480, Mus. Royaux, Brussels), and others deal with general moral themes, often by illustrating human greed and folly in a folkloric way (The Cure of Folly, c.1480–90, Prado, Madrid). Almost all his pictures have some grotesque element, but only a few are dominated by the kind of weird and disturbing imagery from which his name is now inseparable—nightmare visions of monstrous creatures illuminated by the flames of Hell, showing the horrible consequences of sin (The Garden of Earthly Delights, c.1500, Prado). These works have an extraordinarily vivid imaginative power and the subjects are heavily embroidered with subsidiary narratives and symbols, but the basic themes are sometimes quite simple and much of the imagery can be explained in terms of the popular culture of Bosch's age, notably proverbs and devotional literature. In purely visual terms, the monsters he painted have analogies in the strange creatures often seen in the margins of medieval manuscripts and in the gargoyles of Gothic architecture—the cathedral at 's-Hertogenbosch has some fine examples. This connection with popular culture underlines the fact that Bosch worked in a town that was fairly remote from the mainstream of Early Netherlandish painting stemming from Jan van Eyck. He stands apart in technique, too, for his brushwork is vigorous and varied, rather than smooth and precise in the manner typical of the time. (His individuality also comes out in his work as a draughtsman: he was one of the first artists to make drawings as independent works.)By the time of his death, Bosch's reputation had spread far from his own town: in Spain, Queen Isabella (d1504) owned three of his pictures, and in Venice, Cardinal Domenico Grimani (d1523) owned five. Through the medium of engravings his work reached a wide audience and he was influential in the Netherlands throughout the 16th century, although most of the artists who imitated him did so very superficially, turning his deeply serious diabolic imagery into ‘an infernal amusement park, a Disneyland of the afterlife’ (Walter S. Gibson, Bosch, 1973). Joachim Patinir, in his eerie landscapes, and Bruegel, with his vivid sense of the grotesque, were among the few who had artistic personalities strong enough to extend Bosch's vision rather than simply pastiche it, and it was in Spain rather than the Netherlands that he found his spiritual home. Philip II (see Habsburg) was the greatest of all collectors of his work and kept a favourite example (Tabletop of the Seven Deadly Sins, c.1480–90, Prado) in his bedroom at the Escorial. Writing about the treasures of the Escorial in 1605, a Spanish monk, José de Sigüenza, dismissed the idea that Bosch's work was ‘tainted with heresy’. Far from being absurd, as some people maintained, he thought that his paintings were like ‘books of great wisdom and artistic value. If there are any absurdities here, they are ours, not his…they are a painted satire on the sins and ravings of mankind’; other artists depicted ‘people as they appear outwardly’, but only Bosch had the audacity ‘to paint them as they are on the inside’. In Spain, ‘El Bosco’ continued to be respected long after he had been forgotten elsewhere. It was not until the late 19th century that a major revival of interest in him began, and his strange and often apocalyptic imagery has appealed greatly to modern taste, not least to the Surrealists, who regarded him as a forerunner.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)