In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

There could be no better time for Lakeland Arts to host a retrospective of the work of artist Paul Scott. The news this month that the Government has sanctioned the UK's first new coal mine to be built in 30 years – near the Cumbrian town of Whitehaven – has thrown a spotlight on the northern county's industrial heritage.

Artist Paul Scott in his garden

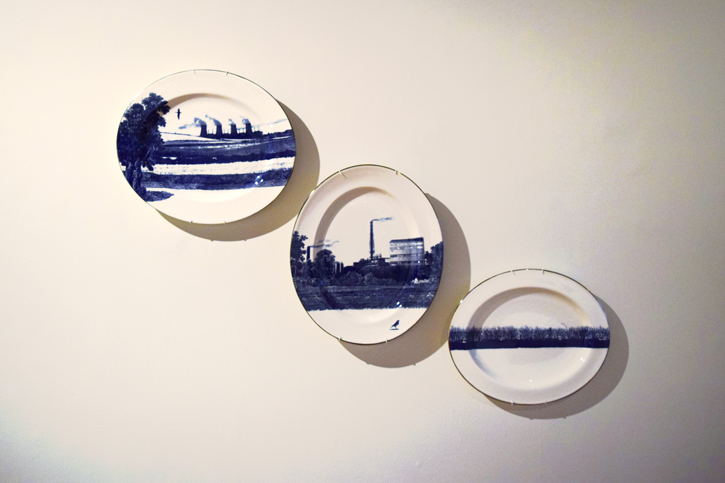

The inland beauty of the Lake District National Park is edged with a coastline that is already home to a nuclear power station and submarine and shipbuilding plant. This stark contrast of heavy industry and dramatic pastoral is used to great effect by the Scott, whose traditional blue-and-white plates demand a second take once you realise they feature Sellafield or a migrant dinghy, rather than a bucolic countryside scene.

Scott's work combines political statement with a sophisticated humour, tackling themes from slavery to the refugee crisis and climate change. Art UK spoke with him about his exhibition 'Cumbrian Blue(s)', which is on show at Blackwell, the arts and crafts house near Lake Windermere, until 2nd January 2023.

Gemma Briggs, Art UK: Can you tell us how Cumbria has influenced your choice of medium, as well as some of the challenging topics you address?

Paul Scott: There's this thing about Cumbria where people think of it only as the Lake District, but a large part of it is post-industrial. People assume it's homogenous but it's a very diverse county. It's still a beautiful coastline, of course. The port of Whitehaven had a pottery, which was started to create ballast for the ships that were going across to North America. It was blue and white transferware, which we always associate with Staffordshire, but it was produced all over the country. It is the medium that I primarily work with and reanimate for the twenty-first century.

British Lakes

ceramic by Paul Scott (b.1953)

I made a blue and white plate with Sellafield on it for 'Hot off the Press', an exhibition I curated at Tullie House, over 20 years ago. I'm interested in those huge industrial sites, there is a perverse beauty in the industrial architecture in the middle of the countryside. I really enjoyed doing the plate. It was just meant to be a one-off, a mickey-take really, but I became hooked.

Traditionally they portray formulaic romantic and fantasy landscapes. My intention has been to put real landscapes on the plates, to bring attention to the fact that transferware isn't an innocent medium. It sort of disseminates a particular view of the world. Many people feel that it showed an innocence and purity or whatever, but it's a selective view of the world. I want to rebalance that with some realism.

Gemma: You've tackled many difficult topics in your work, some of them related to the British establishment's ties with racism, why is this?

Paul: In the exhibition you can see a platter that I own called Cape Coast Castle – it's a particularly beautiful transferware platter by Enoch Wood & Sons. When I first saw it, I was really bowled over because it has a wonderful shell edge border, dark blue, and inside is this maritime scene. When you look at the scene, and you look at the inscription, you start to realise it depicts the Gold Coast of Africa, and the people in the ship are enslaved Africans; it is a slaving ship.

Industrial Legacies – Enslavement

ceramics by Paul Scott (b.1953)

I did more research, and the image on the platter is copied from an engraving, after a painting commissioned by His Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence as part of his campaign against the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The image that was used by the ceramic manufacturer was a piece of pro-slavery propaganda. The discovery of this platter was a very important moment for me because I've always known that transferware tells a particular story. You know that this is a beautiful object but what it depicts is something so awful.

Gemma: Can you tell us about one of your most powerful pieces, which is about the death of at least 21 Chinese cockle pickers who drowned at Morecambe Bay in 2004?

Paul: I was asked to do a piece about the anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade and I remembered those Chinese workers who drowned in Morecambe Bay – these people were modern-day slaves. My intention in creating that tea service was to commemorate the Chinese cockle pickers and make a reference to the original slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were taken across the Atlantic.

Paul Scott's (@cumbrianblues) The Cockle Pickers Tea Service acquired by @SlaveryMuseum for today's #OnlineArtExchange on #tea @artukdotorg.

— Manto Psarelli ◊ Μαντώ Ψαρέλλη (@psarelli) April 21, 2022

Scott has currently a show @BluecoatDisplay & you can also see his ceramics @walkergallery. pic.twitter.com/OIvFoASBrx

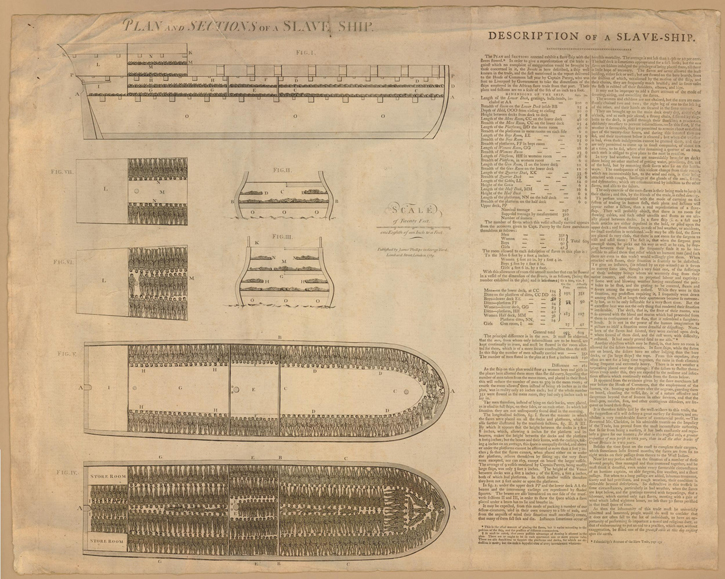

When I made the Cockle Pickers artwork, I didn't know about the Cape Coast Castle platter. One of the strongest weapons of the abolitionist movement was a series of famous images of people chained on boats in appalling conditions, originally published in a broadside sheet, Description of a Slave Ship (1789). I used a detail from one of those engravings on the tea service.

Description of a Slave Ship

1789, broadside print based on the 'Brookes' slave ship

In a way, what I'm interested in doing is making people look again at historic pieces and understand more about our history. When I did my research for the Cockle Pickers tea service I learned an awful lot about the British accumulation of wealth as the result of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. West Cumbria was enriched by that trade, but there is very little acknowledgement of that.

Gemma: Transferware is a mass-produced form of ceramics. How does it feel to show your body of work in Blackwell, which embodies the Arts and Crafts movement?

Paul: I've always really enjoyed visiting Blackwell; its tiled fireplaces are just so wonderful. But I have always felt slightly disconnected from the place because it's very 'arts and crafts'. The Arts and Crafts movement grew out of an animosity to industry, and there was the feeling that anything industrial was poorly made, in bad taste and the design lacklustre. But of course, that was a very selective view. There was no way you could go to Wedgwood and say that their products were substandard design.

Cumbrian Blue(s)

ceramics by Paul Scott (b.1953)

I don't see my work as being at odds with Blackwell and the references that it makes. If you're looking at the craft side of it, my contention is that our industrial factories – the places that designed and made tableware and ceramics – housed enormous reservoirs of skills, crafts and craftspeople. So, I think my works fit perfectly in Blackwell and if it causes some people to question what's perceived as arts and crafts, then I think that's a very good thing.

Gemma: Is the thought of people labelling your practice a source of frustration?

Paul: I feel that the definition of craft itself is very problematic. Handmade processes are labelled as craft, but really it is in all kinds of things we do. I work with industrial processes, I make images and create scenes and prints. I do have a problem with labels in the visual arts. I happen to work with materials that have traditionally been described as the applied or decorative arts. Transferware is way down from porcelain, you know, it's seen as a lower form. But the fact remains that I work with images, with collage, print and with pattern. In that way, I'm sort of promiscuous in my artistic practice.

Gemma: Your work can involve the use of antique pottery, is it correct that some of this you deliberately break?

Paul: I've been buying second-hand antique tableware for years now, and very often the ones that I could afford to buy were broken or cracked. At first, I fused broken pieces and discovered that you could take a Chinese export porcelain image and slide it across a piece of transferware and the two things would join up at one point and make a landscape. So, this object that came from the other side of the world worked together with this piece made in Staffordshire and told a story.

I started playing with those until I realised that using broken pieces was very restricting. I thought, 'why don't I cut some pieces up?' It took a lot of time before I plucked up the courage to cut up a perfectly good piece of antique transferware but once I started, I haven't been able to stop. Some people are very precious about them, but they were produced in their tens of thousands. I just use them as raw material.

Detail of ceramics in Paul Scott's studio

One of the things I was fascinated with when I was buying cracked and broken things was historic repairs. Kintsugi is a Japanese process where you repair broken ceramics but bring attention to the break. I was intrigued that in certain cultures, broken and repaired objects are more valuable than the whole. Kintsugi has become part of my practice and although I'm completely self-taught, visually they do the trick. I've used it in my pieces which are to do with things like fracking, the Fukushima disaster and the Middle East. These cracks allude to breakage, destruction, but also to the money that people are making by exploiting these disconnects.

Gemma: Your retrospective is part of Lakeland Arts' 'Year of Protest' series of exhibitions that have been held during 2022. One of the pieces on display was made during the foot and mouth crisis in the 1990s. It's a brutal piece of work, do you think it shows that ceramics can be a powerful form of art?

Paul: I live in a village [Blencogo, in North Cumbria] and my friends work on the farms; foot and mouth was pretty horrific. There's a place on the road from Wigton to Penrith where there was a pyre on the left and the stink was something else. Leaving our village you'd see either dead cows or dead sheep in fields as you went out, you know?

It was one of those things where I felt it was necessary to record it, to make works which reflected what was going on. Some of them were traditional pastoral scenes by Spode where I just removed the animals, but eventually I thought these works were all a bit too subtle. So, I made this platter with a bold print, a collage of images of the burning cows. Perversely, the legs and hoofs echo those famous images of dancing girls at the Folies Bergère. I put an image of the burning cows on a bone China platter – because it is made from bone ash – and it could be a beef carving platter, of course.

Industrial Legacies – Environmental Exploitation

ceramics by Paul Scott (b.1953)

I wanted to show it at the Beacon Museum in Whitehaven when I was doing my residency there and they threatened not to allow it on the walls because it was too controversial. There was some controversy in the local press about it too – people said it was in 'bad taste'. I thought it was interesting that putting an image of burning cows on a piece of bone china was more upsetting than opening a newspaper and seeing the picture of it. That's what made me realise that ceramics is a powerful medium.

Gemma Briggs, Head of Marketing and Communications at Art UK

The exhibition 'Cumbrian Blue(s): Works by Paul Scott' is at Blackwell until 2nd January 2023