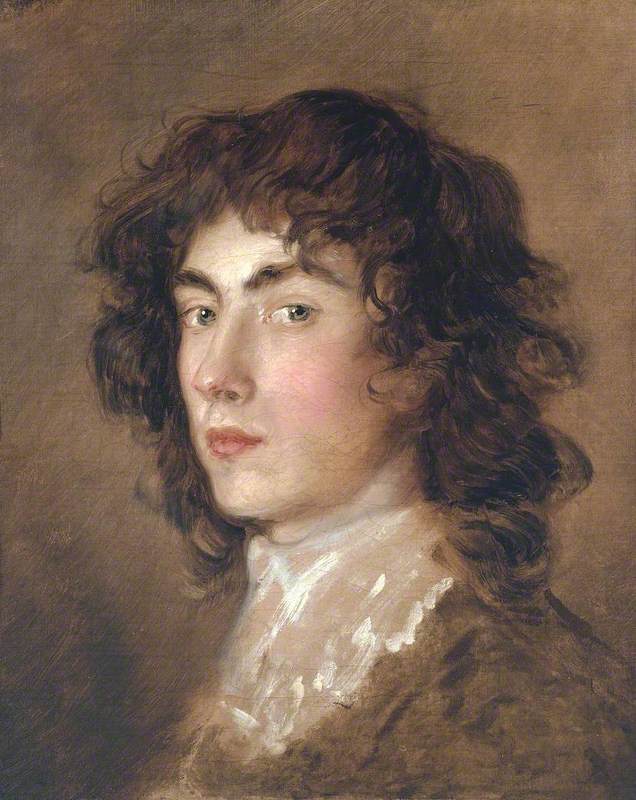

Thomas Gainsborough was one of the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. He was living in Bath at the time with a fashionable clientele for his portraits and took part in the first RA annual exhibitions, held in a private house on the south side of Pall Mall. A few years later, Gainsborough moved to London, precisely to a house in Pall Mall, a short stroll from today's RA. And he soon fell out with the Academy over the hanging of his works.

It was probably as much the press of the day as the artists themselves that stoked up a rivalry between the first President of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Gainsborough. But the two men dominated contemporary portrait painting, competing on the walls of the annual show with their 'performances', as the RA called the works submitted. Reynolds brought classical knowledge and Old Master gravitas to the subject while Gainsborough overcame his distaste for 'people and their damned faces' to paint vivacious and often brilliant studies.

Both artists varied their subject matter with what Reynolds called 'fancy pictures', usually children in a landscape with a moral or literary theme.

But above all, Gainsborough sought to record nature, not wanting to be beholden to clients: 'I'm sick of Portraits and wish very much to take my Viol da Gam and walk off to some sweet Village where I can paint Landskips…'

Cornard Wood, near Sudbury, Suffolk

1748

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Unlike Reynolds, Gainsborough was also a notable draughtsman and a printmaker, but he was supposedly provoked by his rival's range – not only as a painter but as a teacher, writer, and art-world supremo – to say 'Damn the man, he is so various!' But Reynolds bought one of Gainsborough's 'fancy' paintings and the younger man wrote on his deathbed: 'I always admired and sincerely loved Sir Joshua Reynolds.'

The 'sweet villages' for which Gainsborough longed are those in his home county of Suffolk. Today, his childhood home has become the national centre for the study of his work. Gainsborough's House in Sudbury was purchased in 1958 to open three years later as a museum with a fine garden of ancient mulberry, quince and medlar trees.

The collection grew slowly, supported by its first Vice President, Sir Alfred Munnings, another Suffolk artist and past President of the Royal Academy. Exhibitions of contemporary artists were always integral to Gainsborough's House, not least because Suffolk has been home to so many other significant artists – from John Constable to Cedric Morris, John Nash and Maggi Hambling.

In 2019, the museum began to extend its premises and ambition with a £10 million redevelopment. In the same year, just before the coronavirus pandemic affected our lives so drastically, the Royal Academy elected its first-ever woman President, Rebecca Salter: 250 years after Sir Joshua Reynolds.

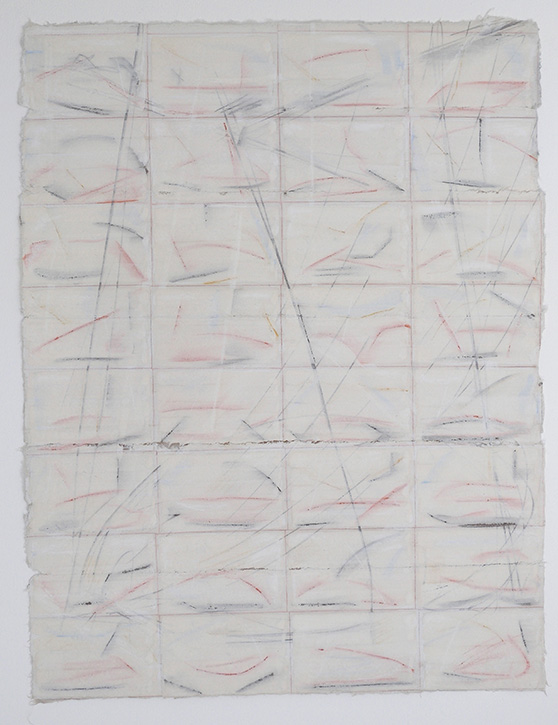

Rebecca Salter in her studio in 2023, featuring Salter's 2019 work 'Untitled AR1'

She was cheered during lockdown, if rather surprised, by regular emails from Gainsborough's House about their new building and successful fundraising. But she was baffled when they finally asked her to open the new centre as she had not been told that, ex officio, the President of the RA is also President of Gainsborough's House.

At the reopening, she was asked if she might restart the tradition of contemporary artists exhibiting in the house. While Salter had a major retrospective at the Yale Center for British Art in 2011, 'In View: Rebecca Salter at Gainsborough's House', is her first museum exhibition in Britain.

The link, apart from the Royal Academy, may not at first be obvious but the complements and comparisons are brilliantly revealing. She is a perfect guest in the house.

Sketchbook

2022, Sumi ink by Rebecca Salter (b.1955)

A sketchbook by Salter from 1990, not shown in Sudbury, can be compared with a later one of 2022 in the show, both capturing the Lake District landscape on her regular visits.

Gainsborough also travelled to the Lakes to add mountainous views to his repertoire.

In a piece of bark from the Lakes, Salter saw the potential for a sculptural response to the outline of a mountain's peak. This echoes Gainsborough's practice of recreating landscapes from stones, twigs, and even broccoli when forced to work in his city studio.

Sculpture

2012, wood by Rebecca Salter (b.1955)

With curator and writer Thomas Marks, Salter chose works on paper from the Gainsborough House collection not only by Gainsborough but also by Rembrandt van Rijn, John Sell Cotman and Cedric Morris. These are hung with her own works emphasising subtle similarities of material and texture, and sometimes allusions to shared subject matter. A second gallery displays her larger works on their own: monochrome, abstract but often with reference to a horizon line or a vertical gap that invites the viewer to enter.

Untitled AR1

2019, mixed media on muslin on linen by Rebecca Salter (b.1955)

Salter began her career as a ceramicist and then studied in Japan for many years, studying drawing and printmaking. The smaller of the two galleries is painted light grey and has a curved wall which gives a sense of being held within a ceramic vessel.

Salter talks of the Japanese philosophy of learning expertise and then 'unlearning for freshness', which evokes the speed and elegance of much of Gainsborough's works on paper and the treatment of fabric in his formal portraits. Sudbury had a small silk weaving industry at the beginning of the eighteenth century but nearly 95 per cent of Britain's woven silk is produced there.

However simply glamorous and fashionable some of Gainsborough's portraits appear at first sight, their bravado of materials, especially silk, is carefully and finely wrought. While Salter is a twenty-first-century woman who produces meticulous abstract monochrome works, she and Gainsborough share many approaches, including an appetite for texture. For Salter, the surface on which she works, whether Japanese paper, muslin or linen, is permeable, inviting the viewer to look beyond and within, in the Japanese manner.

F137

1989, mixed media on Japanese paper by Rebecca Salter (b.1955)

Two works may at first seem total opposites but the swiftness of Salter's F137 (1989) has the same energy, verve and even range of colour as Gainsborough's sublime portrait of Lady Howe.

Gainsborough's depiction of Pomeranians, on loan to Sudbury from Tate, was painted as a tour de force of just those characteristics and shows a sensual delight in texture.

As well as recreating the atmosphere of Gainsborough's childhood home, the new museum celebrates printmaking. Two distinguished printmakers, Daphne Reynolds and Valerie Thornton, opened a print workshop within Gainsborough's House in 1979. While she was in Kyoto, Salter studied Japanese woodblock printing and has written two books on the subject. To mark the 250th anniversary of the RA, Salter produced a laser-cut woodblock print, not seen.

Like Gainsborough, Salter is deeply concerned with the types of paper on which she works. She discovered a letter from her fellow artist in the RA archive in which Gainsborough writes of spoiling a fine piece of drawing paper in his haste and, in response, she talks, with reference to not seen, about how she evokes the element of time:

'My work is incredibly detailed, obsessive really, and there's a correlation between the time it takes for me to make works and time it takes people to look at them. There's a term in Japanese: "your eyes sit". It means that you stop actively looking – the muscles in your eyes relax, you start seeing things in a much more receptive way because you're not as active in the way that you're looking. So that's what I want people to do.'

Wastwater panorama

Wastwater panorama, 2009, watercolour on paper by Rebecca Salter (b.1955)

Gill Hedley, writer and curator

'In View: Rebecca Salter at Gainsborough's House' is showing at the Suffolk museum and gallery until 10th March 2024