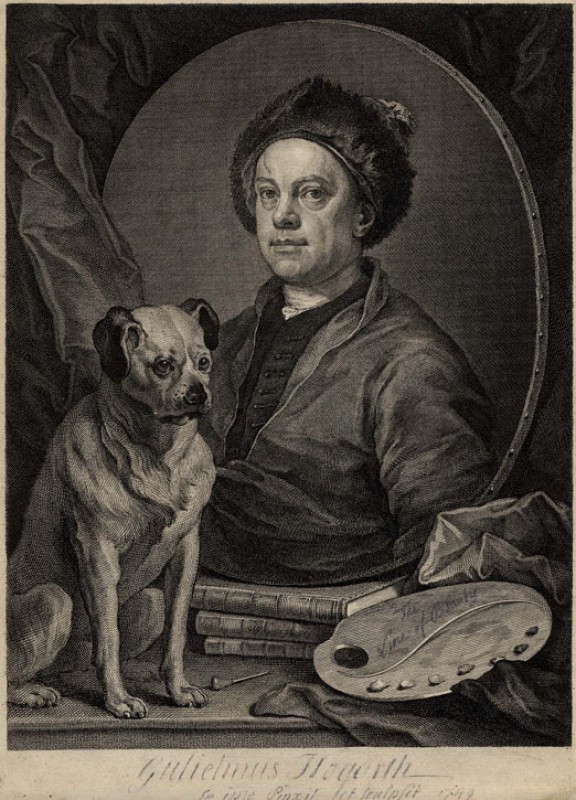

(Born Plympton [now a suburb of Plymouth], Devon, 16 July 1723; died London, 23 February 1792). English painter and writer on art. Reynolds was the leading portraitist of his day, the first president of the Royal Academy, a major art theorist, and perhaps the most important figure in the history of British painting, for through his social and intellectual eminence he raised his profession to a new level of dignity. He was the son of a scholarly clergyman, and was brought up in an atmosphere of learning (he said he owed his ‘first fondness’ for art to Jonathan Richardson the Elder's Essay on the Theory of Painting, which he read in his father's library). From 1740 to 1743 he studied painting in London under Hudson (likewise a Devonshire man), then set up independently as a portraitist a year before his apprenticeship was due to end (the parting was amicable—he and Hudson remained on good terms).

Reynolds quickly achieved a leading position in his profession. He had 150 sitters a year by 1758, and by 1764 was earning the enormous annual sum of £6,000 (his career is exceptionally well documented, as many of his ‘sitter books’ and financial ledgers survive). His success was achieved through hard work and careful business management as well as talent: he sometimes worked on Sundays (to the dismay of his pious relatives) and on the day he was knighted (21 April 1769) his visit to St James's Palace was fitted in between two sittings with clients. Moreover, although he always retained traces of his provincial origins (notably his Devonshire accent), he was completely at home with his eminent sitters. His pupil James Northcote said that ‘His general manner, deportment and behaviour were amiable and prepossessing; his disposition was naturally courtly. He…contrived to move in a higher sphere of society than any other English artist had done before. Thus he procured for the Professors of the Arts a consequence, dignity and reception which they never possessed in this country.’ Reynolds's elevation of the status of the artist depended, then, not only on the intellectual quality of his work, but also on his social acceptability, and it is significant that his friends were mainly men of letters—notably Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith—rather than other painters (James Boswell dedicated his celebrated Life of Johnson to Reynolds).

On the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768, he was the clear choice for president (even though George III preferred the work of Gainsborough and Ramsay), and he arranged for Johnson and Goldsmith to be appointed to the honorary positions of professors of ancient history and literature. Between 1769 and 1790 he delivered a series of lectures to the Academy's students, and these fifteen Discourses are one of the most impressive bodies of writing ever made by a practising artist, forming the classic expression of the academic doctrine of the Grand Manner (each Discourse was published separately and the first collected edition appeared in 1797). In 1789 failing eyesight forced Reynolds to give up painting and by the time of his death he was almost completely blind. He bore his final illness with what his friend Edmund Burke (see Sublime) called a ‘mild and cheerful fortitude’ and was buried in St Paul's Cathedral with ceremonial never before accorded a British painter: his ten pallbearers were made up of three dukes, three earls, two marquesses, a viscount and a baron.

As a portraitist Reynolds is remarkable above all for his versatility—his inexhaustible range of response to the individuality of each sitter: man, woman, or child. The famous remark of his rival Gainsborough, ‘Damn him! How various he is!’, is echoed in the praise of Ruskin: ‘Considered as a painter of individuality in the human form and mind, I think him the prince of portrait painters. Titian paints nobler pictures and van Dyck had nobler subjects, but neither of them entered so subtly as Sir Joshua did into the minor varieties of human heart and temper.’ His huge output necessitated the employment of assistants and drapery painters, and his experimentation with bitumen has resulted in some of his pictures being in poor condition, but there is nevertheless much beauty of handling in his work, and his finest pictures rank among the great masterpieces of British portraiture. On the other hand, his history paintings, dating mainly from the end of his career, are generally considered ponderous failures (Hester Thrale—a friend of Dr Johnson—said he had ‘a rage for sublimity ill-understood’).

Reynolds's work is in numerous public collections, great and small, in Britain and elsewhere, and many of his best pictures are still in the possession of the families for which they were painted. His output was so varied that no single collection can be regarded as fully representative. Frances Reynolds (1729–1807), Sir Joshua's sister and for many years his housekeeper, was an amateur painter, but evidently not a very good one, for he said of her copies of his work: ‘They make other people laugh and me cry.’

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)