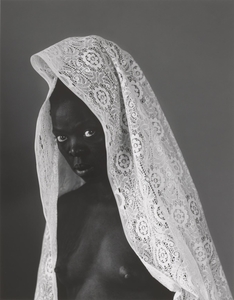

The South African visual activist Zanele Muholi serves to empower and educate their audience in equal measure. Muholi's work, consisting of documentary and portrait photography, is unlikely to be forgotten once you lay your eyes on the rich dark hues that dance and sing on each glossy print.

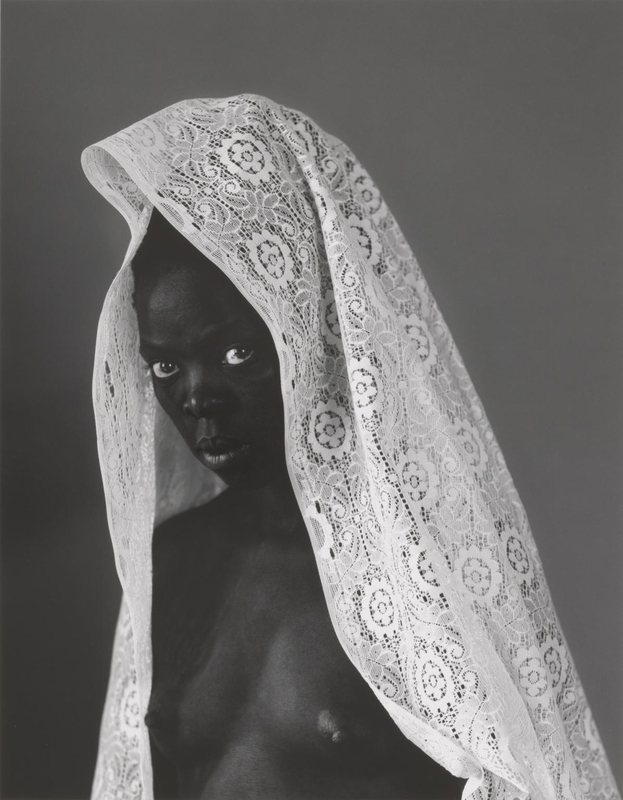

Ntozakhe II, Parktown

2016, photograph, gelatin silver print on paper by Zanele Muholi (b.1972)

This autumn, Tate Modern was due to present the activist's first major UK survey from 5th November 2020 until 7th March 2021, though the launch will now happen once the national lockdown is eased in early December. Many Londoners will have the opportunity to view Muholi's work up close and personal for the first time, but be warned – their work will find a crevice in your heart and reside there long after you've walked out and re-entered the world.

Muholi's oeuvre is a long and winding one that pays tribute to Blackness, history and identity in all of its forms. Muholi was born in 1972 in the fourth largest township in South Africa, a suburb called Umlazi. Now the visual activist lives over 500km away from home, switching between Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town. They identify as non-binary and prefer to be called a visual activist, rather than an artist. Muholi's own background is integral to the message that weaves each photographic collection together: your identity is yours and yours alone.

Across the 260 images presented in the exhibition, each work depicts the lives of the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. Those seen holding, laughing and embracing one another are referred to by Muholi as participants, rather than subjects. In an interview with Tate, the activist reinforces their relationship with their participants: 'To say they're subjects, we're divorcing ourselves from the human-to-human connection that's supposed to happen.'

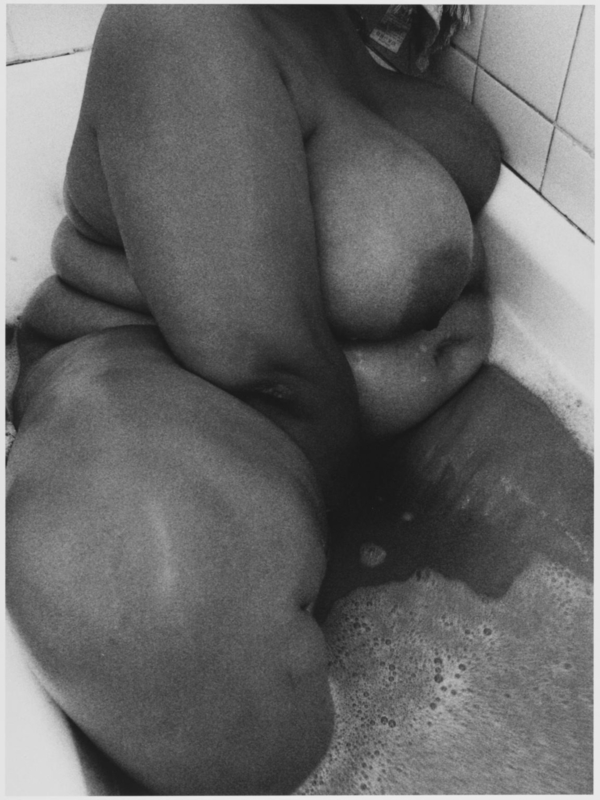

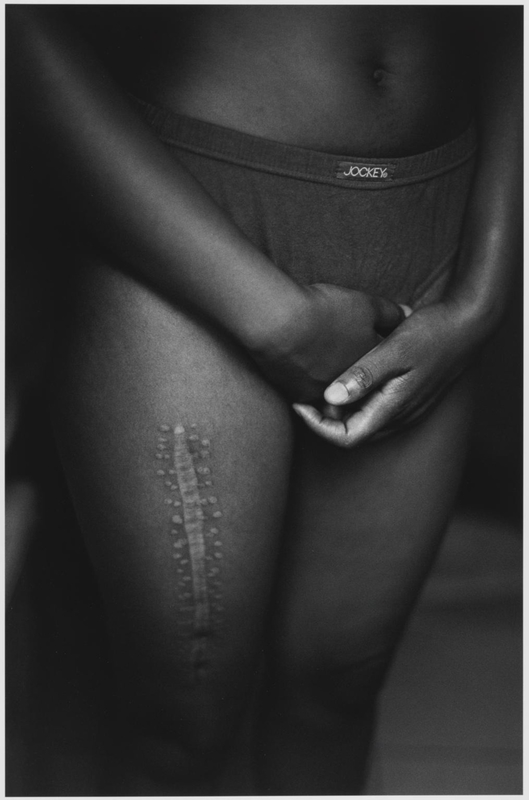

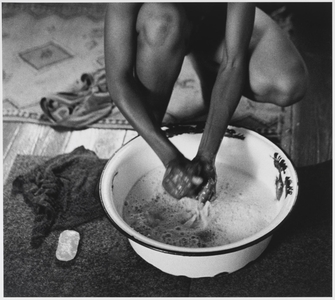

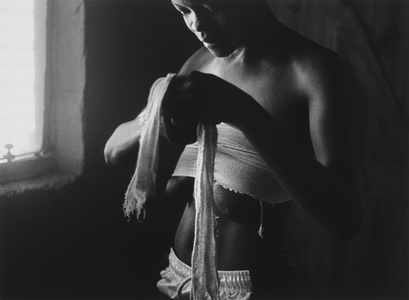

Upon entering the Tate Modern you'll be met with black and white images that confront a variety of taboos – all centring on intimacy and the private worlds of LGBTQIA+ people. From a naked woman washing in the bath in Flesh II (2005) to a young individual wrapping a binder around themselves to conceal their breasts in ID Crisis (2003) – we are offered a brief glimpse into a special world.

Muholi grew up in the midst of chaos and racial segregation, as apartheid's grip on South Africa reigned on. Implemented in 1948 under the National Party, apartheid promoted devastating disconnect and conflict, and was justified by the white minority regime. When considering the context in which Muholi grew up in, Tate curator Kerryn Greenberg tells WePresent: '[Muholi] is trying to humanise the "other" to show that we have so much more in common, and for me, that's where the power lies.' Kerryn goes on to dub the visual activist as a 'nurturer, consoler and guardian to their community.'

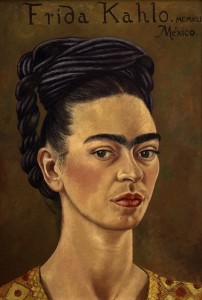

In a bid to control one's own image and to bring about positive visual narratives, Muholi picked up the camera and began to carve out space for the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa and beyond. With the 'other' firmly rooted at the centre of Muholi's work, the series Only Half the Picture (2002–2006) marks the beginning of their foray into the world of photography. In 2004, the series was exhibited at Johannesburg Art Gallery and was met with adoring fans, critical acclaim and many years later, international recognition.

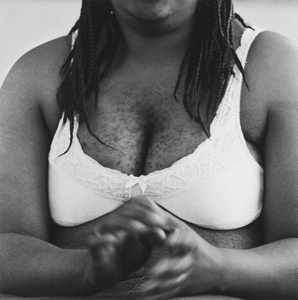

Only Half the Picture focuses on skin: its richness, versatility and texture. Body politics is explored in all of its glory, showcasing beautiful scars as seen in Aftermath (2004), and human blood and luxuriant hair, as seen in Bra (2003). Muholi has said that this is a part of politicising spaces in a conscious way – forcing those in power to acknowledge a community that has thus far been ignored. Muholi reiterates: 'We want to bring about change in spaces that are queer-phobic.'

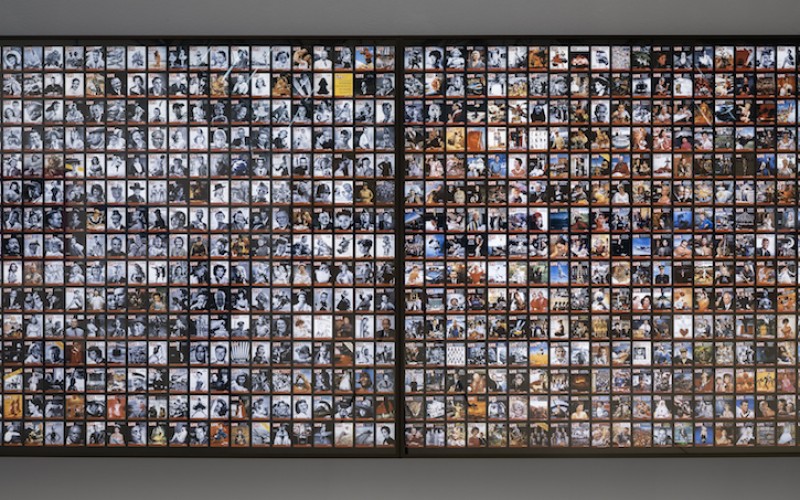

Faces and Phases (since 2006) is a bold and powerful series of portraits documenting Black lesbians, bi, trans and gender non-conforming individuals in South Africa and beyond. The images have all been shot in black and white, and are presented in a grid format, providing incredible visibility to a number of stories. Often the images are paired with testimonies that narrate and acknowledge the suffering and experiences that have led them to stand in front of Muholi's gazing lens.

At once, the viewer is held in captivating eye contact with the participant, forcing them to confront a community that has long been overshadowed, hurt and abused. But, do not be fooled – Muholi does not intend to create an image of victimhood. Instead, they unveil the strength and healing nature of community, acceptance and friendship.

Since the Civil Union Act in 2006, same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa, promising protection for all members of society regardless of their sexual orientation. This was a huge moment for Africa, as South Africa was the first country in the continent to make such a move. Regardless of the legislative laws put in place to protect LGBTQIA+ people, discrimination and unfathomable acts of violence against them is rife across South Africa. Hate crimes including corrective rape and mutilation are only some of the issues being tackled by activists and human rights organisations like the Triangle Project, and the organisation co-founded by Muholi, Forum for the Empowerment of Women.

According to a survey conducted by the Triangle Project, 41% of respondents say that they know someone who has died due to gender-based violence. Faces and Phases and trans(figures) (2010–2011) are some of the many series that directly respond to the injustices seen on the streets of South Africa.

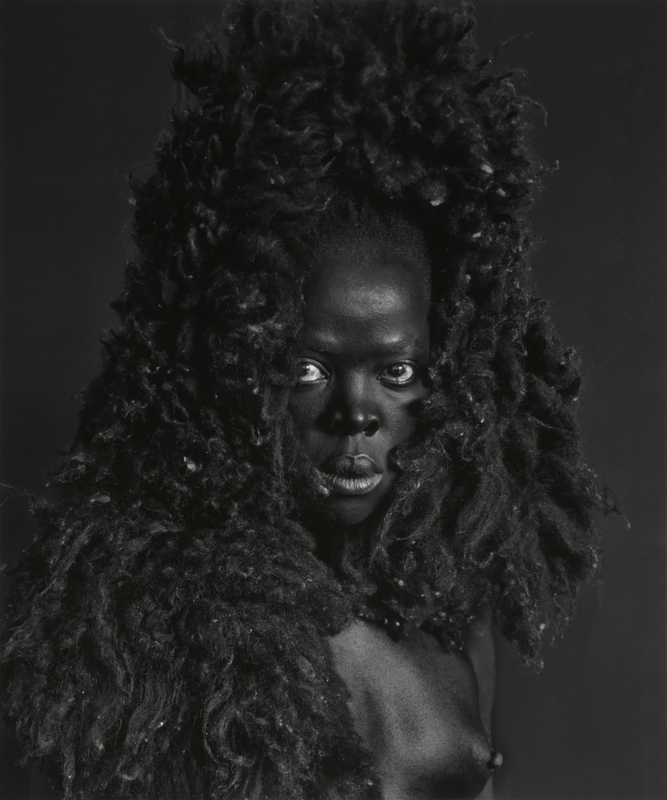

Miss D'vine II

2007, lambda print by Zanele Muholi (b.1972)

Muholi's remarkable tenure includes a number of other collections, like Of Love and Loss (2014), where they juxtapose images of funerals and weddings to portray the intersection of the joyful and the painful. As one LGBTQIA+ person gets married, another is killed all, within the same democratic structure. The images exude intimacy and protection – once again, Muholi has made the private public in order to drive home change for their community.

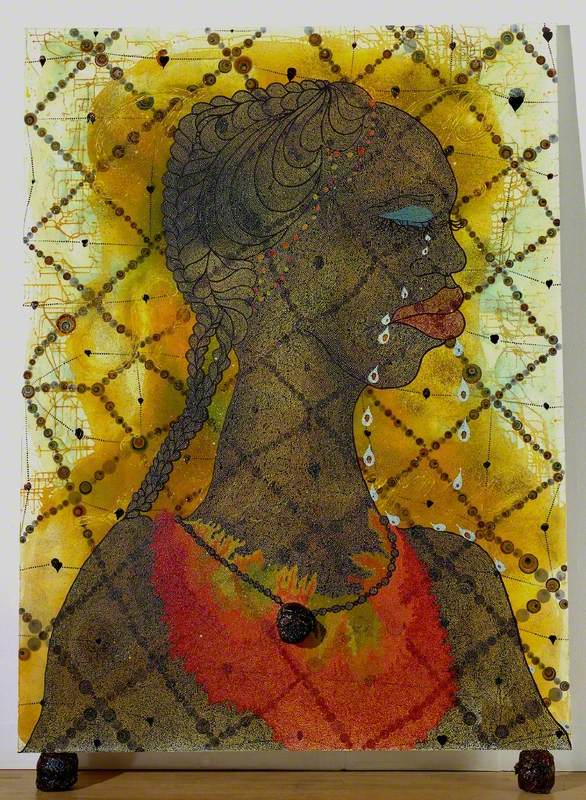

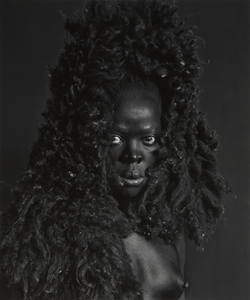

Brave Beauties (since 2014) is another captivating collection that shines a light on trans women, some of which are former beauty queens. Muholi states: 'All I want to see is beauty' in response to the formation of the series. The Tate Modern survey will also exhibit Muholi's most recognisable series Somnyama Ngonyama (since 2012) meaning 'Hail the Dark Lioness' in Zulu.

It was first exhibited in the UK at Autograph in 2017 and sees Muholi pictured in front of the camera once again. The visual activist is hard to ignore – their rich Black skin and the stark whites of their eyes stand in direct contrast to the everyday objects surrounding them.

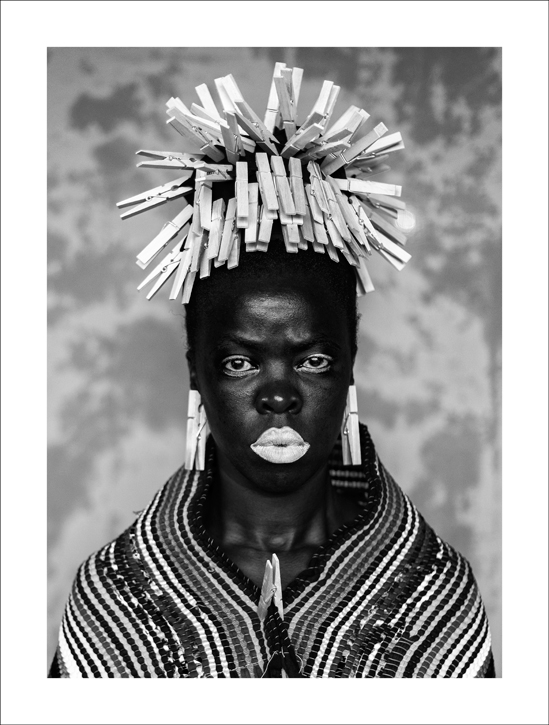

Somnyama IV, Oslo (2015) exhibits Muholi from the chest up, gazing intently into the camera. Another striking image is Bester I, Mayotte (2015) where Muholi has wooden cloth pegs attached to their hair – fanned with intricate detail. Muholi here is making use of the ordinary and the mundane to create profound art, weaving together a narrative around domesticity, ancestry and poignant historical moments from their own life.

Bester I, Mayotte

2015, photograph, silver gelatin silver print on paper by Zanele Muholi (b.1972)

Somnyama Ngonyama has provided Muholi with an opportunity to explore their own pain and discomfort. They tell Tate: 'The project addresses my own experiences in our society head-on: things that are painful, and I would not expect anyone else to carry that with me. I had to do it myself.'

As previously mentioned, once you are introduced to Zanele Muholi, it is difficult to live your life without drawing upon their artistry. Faces have never been more important, and the ones presented by Muholi refuse to be forgotten and shoved to the back of the wardrobe. They are occupying space, space that has been long overdue in a country that feigns responsibility. On entering the Tate survey, you will experience solitary moments with each face – embrace them and acknowledge the necessity in these stories, how crucial it is that they are out there, roaming free in the world.

Siham Ali, freelance writer

Zanele Muholi's survey show is planned to reopen at Tate Modern once lockdown is eased on 2nd December 2020.