What drives people to represent animals in art, tigers especially? What roles do they fulfil in paintings and sculptures? Looking over the tigers in the Art UK database I'm more and more convinced that you could tell the history of art purely through representations of tigers. While I can't promise to do that in this story, I can hopefully give you a sense of the range of representations that are out there – and persuade you to take a closer look at some of them yourself.

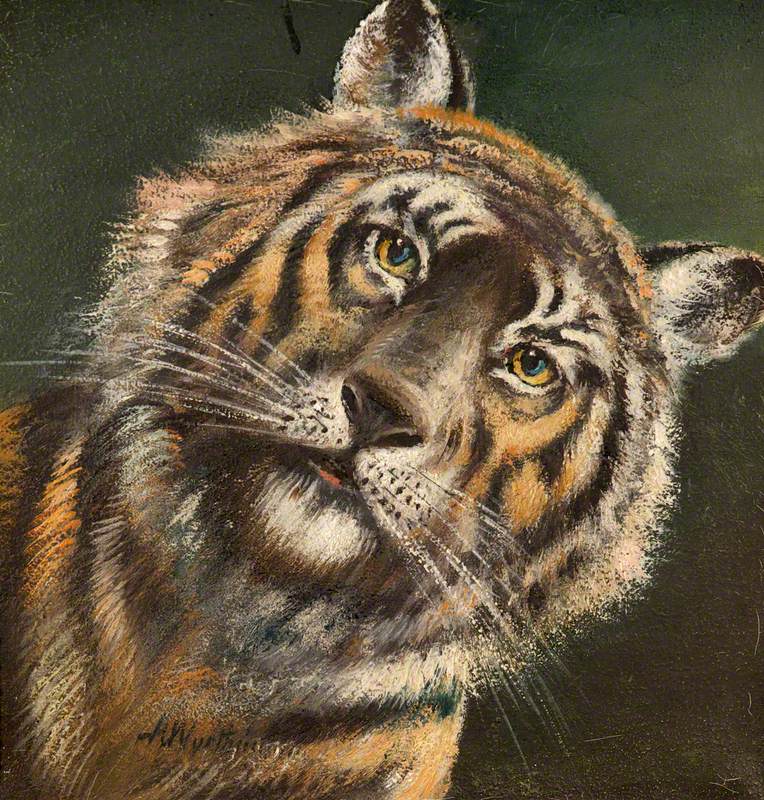

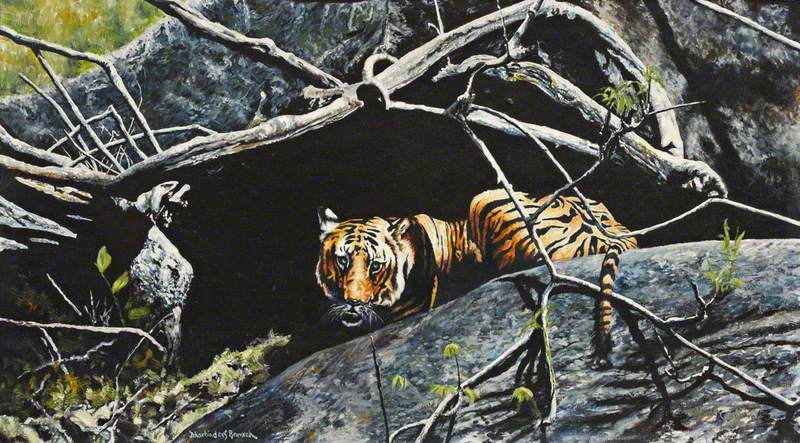

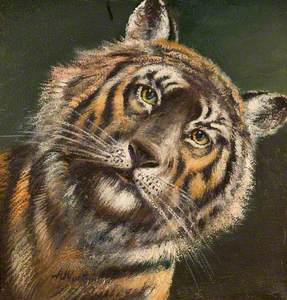

Tigers are hard to see in the wild. One reason for that is that they are shy, secretive animals, with a talent for keeping hidden. The spectacular black, orange, and white of their fur may stand out in some contexts, but in most of the habitats in which tigers have traditionally lived, their striped coats have helped them blend in (alluded to in William Redgrave's wonderful painting above).

The other reason that tigers are hard to see in the wild is that there are very few of them to be found there. In recent decades, tigers have become very closely associated with the conservation movement, especially in India. Some have questioned the wisdom of concentrating so much attention and funding on just one charismatic species.

However, the numbers remain startling. The IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) estimates that numbers of wild tigers have fallen from around 100,000 to less than 4,000 in the last century. During this period the tiger has lost more than 93 per cent of its historic range. No wonder tigers are hard to see.

For an art historian like me, tigers are nevertheless a familiar sight. As I explore in this story, there is no shortage of tigers in museums and art galleries across the UK. In fact, one of my first memories of an art gallery involves a tiger. For many children the highlight of a visit to London's National Gallery is Henri Rousseau's Surprised!

I remember my own surprise on first seeing this huge painting of a tiger caught in a storm in a jungle. I recall equal astonishment at encountering Edward Armitage's similarly large Retribution, a rather more bloodthirsty painting that used to hang in one of the ground floor galleries of Leeds Art Gallery.

While these two tiger paintings represent only the tip of an iceberg of tiger-related art, they have qualities that are typical. In both cases, they were certainly made by artists who had never seen a tiger in the wild. Rousseau never left Paris, and relied on zoological specimens, taxidermy, and other artists' impressions, to construct his picture. Armitage, who never went to India, would have leaned on similar sources to piece together his painted tiger.

But maybe realism wasn't their goal: these were never intended to serve as visual aids for the natural sciences. These tigers, like most of those that appear in nineteenth-century paintings, have more of a symbolic function.

In Armitage's case, the tiger represents the Indian Rebellion of 1857 being ruthlessly quashed by the figure of Britannia on the left. It's a tasteless example of imperial propaganda.

Rousseau's tiger is harder to read, but his so-called 'jungle paintings' are often understood as colonial fantasies, serving up a slice of the exotic for western audiences.

The theme of Empire is central to many representations of tigers, whether explicitly (as in the case of Armitage, or Tipu's Tiger in the V&A) or implicitly, as in the case of Indian works of art that have entered British collections through imperial networks.

More generally, the theme of violence against tigers is unignorable. Although tiger populations suffered their greatest dip in the last two centuries, humans have been hunting tigers, or imagining tiger hunts, much longer than that.

The fearsomeness of the tiger has proved irresistible to artists across all cultures – and the institution of the tiger hunt has clearly held an important symbolic function.

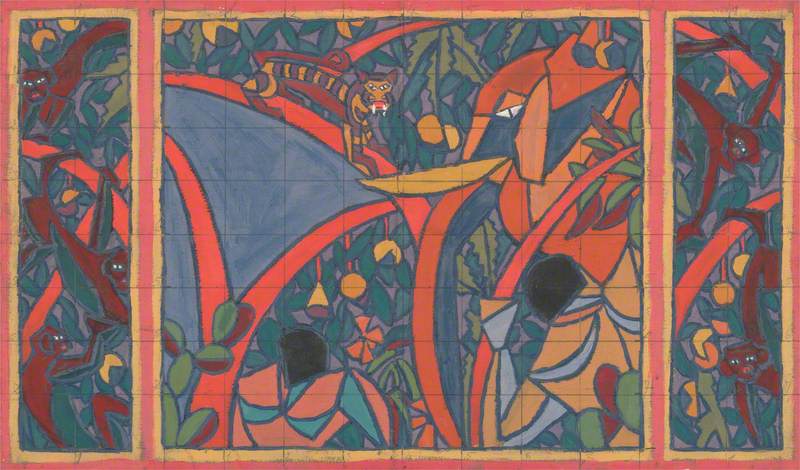

Design for Tiger Hunting Mural in the Cabaret Theatre Club

1912

Charles Ginner (1878–1952)

To kill a tiger, the largest and reputedly the strongest of the big cats, has long been seen as a test of masculinity. Could it be that what is surprising the tiger in Rousseau's painting is an off-stage hunter with a gun? Such a scenario is brought frighteningly to life by Henry Whiting of Norwich, whose own Tiger Hunt leaves us in no doubt as to the effect that firearms would have on the balance of power between man and tiger.

Hatwell's 'Gallopers': Tiger Hunt

(bottom centre panel)

Henry Whiting (c.1839–1931)

Paintings and sculptures of people, or other animals, attacking tigers are all too common – as, sadly, are images of dead tigers.

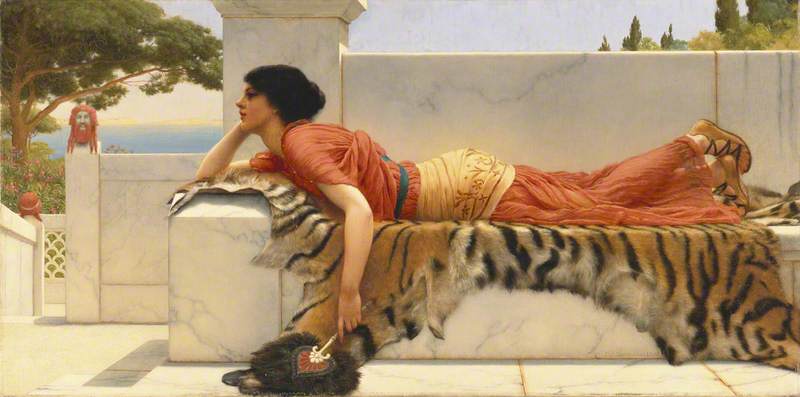

Many of these seem pleasant enough at first sight. For instance, the artist John William Godward specialised in paintings of young women lounging around in faux-classical settings. On the Balcony represents three young women enjoying a summer afternoon in a house overlooking the Mediterranean.

Expectation, meanwhile, portrays a single woman lying with a feathered fan in a similar setting, anticipating what we may presume is the return of a lover.

In both cases, a tiger-skin rug offers a soft cushion for the hard white marble. Such rugs regularly appear as props in Victorian paintings, usually juxtaposed with young women.

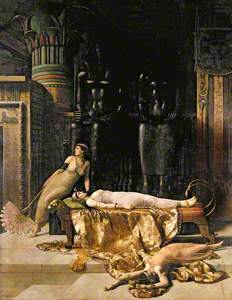

John Collier goes a step further in some of his works. In The Death of Cleopatra, the Queen lies dead on a couch sculpted into the shape of a lion, which sits on a tiger skin.

The mythological Young Girl Draped in a Tiger Skin represents a tiger skin robe.

Young Girl Draped in a Tiger Skin

(once said to be Bacchus)

John Collier (1850–1934)

Evidently both Godward and Collier owned, or had easy access to, tiger skins: not surprising when you consider the tens of thousands of tigers that were shot by British colonialists in the nineteenth century. Tiger skins, imported back to Europe in large numbers, became a fashionable commodity and source of intrigue.

Another late-nineteenth century painting, by the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens, presents another perspective on the fashion for tigers.

In The Present a young woman stares at a miniature tiger on a table. It is, as the title suggests, a gift from a friend or lover. It's not clear whether the gift is appreciated (she strikes me as a little bemused), but it's likely that the sculpture represents the wider trend at the time for historical Japanese art.

Although tigers haven't lived in Japan since prehistoric times, they have always formed a key part of Japanese culture. Here, as in Chinese art as well, they take on a range of roles, as evidenced by objects in two major collections: The Oriental Museum in Durham, and the Wellcome Collection in London.

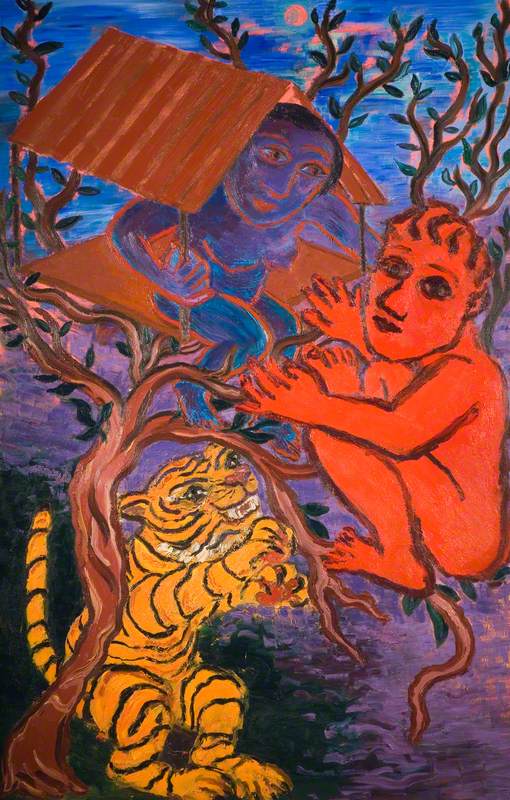

Many of these works are related to Buddhism, and view relations between humans and tigers in a different way. In one Jataka tale, recounting a past life of the Buddha, Prince Sattva sacrifices himself to feed a hungry tiger.

Meanwhile, Hattara Sonja, a disciple of the Buddha, was depicted with a companion tiger.

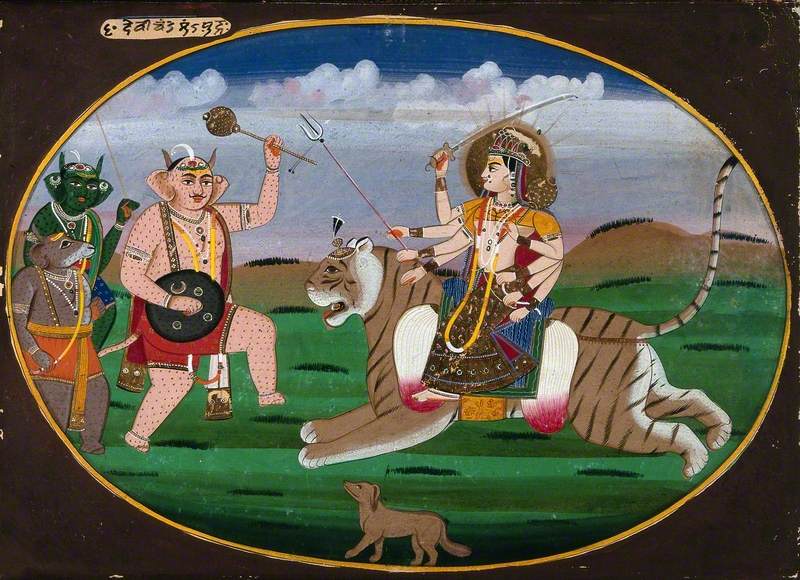

The theme of the tamed tiger also appears in Hindu art. Tigers appear most commonly in images relating to the Hindu goddess Durga, who is usually represented riding a tiger.

The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Mahishasura

19th C

unknown artist

Another Hindu image from the Wellcome Collection shows the sage Rishi Vyaghrapada – a holy man, and devotee of Shiva – with the legs of a tiger.

During the twentieth century, understanding of diminishing tiger populations, and growing awareness of conservation issues in general, meant that images of tiger hunts became less common. This doesn't mean that tiger hunting didn't – and doesn't – still exist: sadly, it very much does. It simply means that artists have largely sought to represent tigers less as ferocious killers, and more as noble victims.

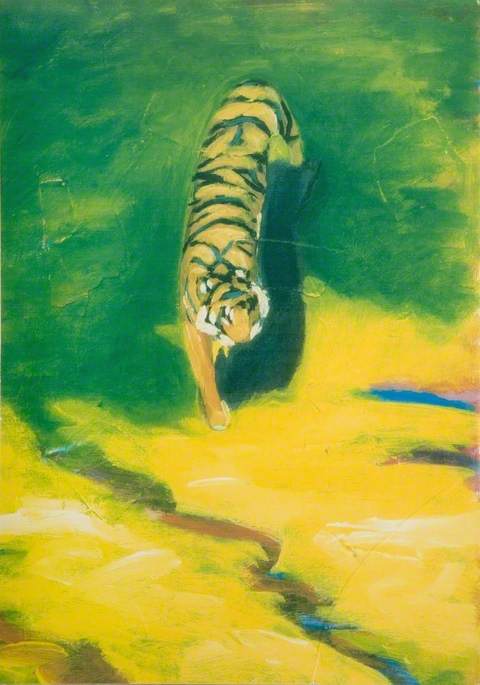

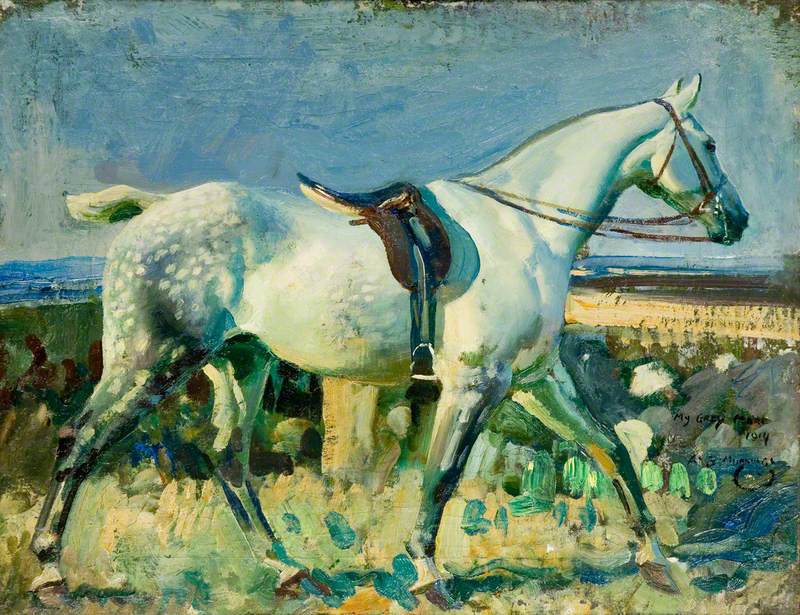

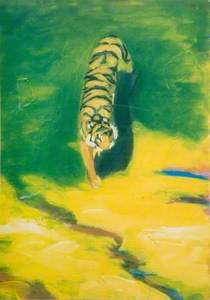

When I looked at the tigers on the Art UK database with my nine-year-old son, he was drawn to paintings made in the latter half of the twentieth century – paintings that echoed his own experiences of seeing tigers on natural history documentaries. Some of these appear to show tigers in their natural habitats.

However, it is very likely that they were painted either from photographs, or from animals in captivity. At least one of them – Tiger, by an unknown artist – shows clear signs of being painted from an animal in a zoo.

Looking down on a tiger from above is the kind of view you are likely to have in such places, where animals are often situated in sunken enclosures.

A final theme demands discussion. As I wrote above, Henri Rousseau's tiger represented one of my earliest encounters with a tiger in art. By that age, however, I had already encountered many tigers in prose and poetry, from Judith Kerr's The Tiger Who Came to Tea, to Shere Khan in Kipling's The Jungle Book (perhaps better known through its Disney adaptations), and William Blake's famous poem The Tyger.

View this post on Instagram

These texts represent tigers with varying degrees of realism; nonetheless, you can't deny their cultural appeal, reflected in public art collections. There are currently three artworks on Art UK called Tiger, Tiger, (and several more with the 'tyger' spelling) in homage to Blake, and one sculpture of Shere Khan.

One final image. Given the complex relationship between humans and tigers, most of the artworks discussed above raise issues that are important yet troubling. Images of humans hunting and killing tigers are not pleasant to look at. For this reason, I was somewhat relieved to come across Edward Bawden's linocut Girl with Young Tiger.

Unlike Alfred Stevens's earlier painting, in which a young woman receives a Japanese tiger sculpture as a present, here a young woman presents a living tiger to a man. His resulting astonishment, and the smile on her face, are hard to forget.

Samuel Shaw, Lecturer in History of Art at the Open University, and co-founder of Art and Ecology, a project that brings together historic objects from collections across the UK to change public understanding of today's ecological crisis

Samuel's 2018 book, Zebra, was published as part of Reaktion's Animal Series

This content was supported by Freelands Foundation as part of The Superpower of Looking