As a distinct artistic form, marine painting appeared and matured in no more than a long lifetime. Ships and the sea feature in medieval European religious art but turning them into a specialist subject is credited to Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom (1566–1640) of Haarlem.

Attack on Spanish Treasure Galleys, Portugal

1602

Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom (1566–1640)

A much-travelled young man, he had started as a painter of ceramics and religious works before concentrating on marine subjects. In these, he already had a European reputation by the 1590s, when the Lord Admiral of England, Howard of Effingham commissioned him to paint designs for the Armada Tapestries that were lost when the old House of Lords burnt down in 1834.

The Spanish Fleet anchored off Calais, attacked by fireships

(from tapestry hangings in the House of Lords), 1739, print by C. C. Lempriere and John Pine

Vroom worked in the colourful Flemish style of the Catholic southern Netherlands but his pupil and son-in-law Jan Porcellis (1580/1584–1632), after mastering this himself, pioneered a more tonal 'grey' manner that became associated with the Protestant Dutch northern provinces.

One of Porcellis's pupils, Simon de Vlieger (1601–1653), combined characteristics of both and was an early teacher of Willem van de Velde II (1633—1707), whose principal master was his own father.

Willem van den Velden [van de Velde], Ships Draughtsman to King Charles the II

18th C, engraving by Gerard Sibelius (1734–1785) after Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) ![Willem van den Velden [van de Velde], Ships Draughtsman to King Charles the II](jpg/pu2659-edited-1-1.jpg)

He was Willem van de Velde I (1610/1611–1693), born as the son of a Flemish barge master, but who became a noted marine artist in Amsterdam. Although he painted well in oils, Willem 'the elder' was primarily a fine draughtsman whose now widely unfamiliar speciality was 'pen-pictures' or 'grisailles' (penschilderijen in Dutch). The example below, of a battle in the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654), shows him making the record sketches on which it is based in the foreground galliot, which the Dutch navy provided for him to do so.

The Battle of Scheveningen, 10 August 1653

1655

Willem van de Velde I (1611–1693)

These penschilderijen were often very large ink drawings on a prepared white canvas or panel that, although looking like engravings at a casual glance, were intricately detailed individual artworks. Willem the elder and Heerman Wesselsz. Witmont of Delft (c.1602–1684) were the leading marine masters of them, Witmont being known for little else.

The Battle of the Gabbard, 2 June 1653

after 1653

Heerman Wesselsz. Witmont (c.1602–1684)

The downside of the form was taking two or three months to complete, limiting sales to a high-paying and relatively limited clientele: oil paintings – made in a few days, or only a week or two – offered a steadier return from a wider market, not least by being easily replicable as versions with the customary help of studio assistants.

The outcome, by the early 1650s, was Willem van de Velde I's official presence at sea to record the actions of the Dutch fleet in on-the-spot drawings, from which he made both his high-status 'pen-pictures' and competent – rather than aesthetically exceptional – paintings.

The Battle of the Texel (Kijkduin), 11–21 August 1673: The Engagement of the Two Fleets

c.1673

Willem van de Velde I (1611–1693)

This oil of The Battle of the Texel (Kijkduin) is a typical example of the sort of aerial view painted by Willem the elder, including those converted to tapestry designs.

Willem van de Velde II, by learning from and helping his father with oil paintings, soon became a much finer master of them. This brought him youthful fame at home and later as a founding figure of the British school, in which flattering comparisons to him became a high form of praise.

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707), Painter

1660–1672, oil on canvas by Lodewijk van der Helst (1642–1684)

Lodewijk van der Helst's portrait of Willem the younger, probably painted in the late 1660s, includes a sea battle behind. His right forefinger points towards a Van de Velde signature in the drawing that he holds, either by him or perhaps his father. (The painting is in the current exhibition at the Queen's House, Greenwich, on loan from the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.)

An early third member of the 'family firm' was Willem van de Velde II's younger brother Adriaen (1636–1672), who was mainly a landscape painter, but sometimes collaborated in coastal scenes, as in the following example.

A Frozen Waterway with Three Icebound Ships

1660s

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707) and Adriaen van de Velde (1636–1672)

In 1672, with the economy of the Netherlands hard-hit during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, Charles II issued a general invitation for Dutch artists and craftsmen to come and work in England. Some only did so briefly but among those who settled were the two Willems. Further impulses may have been the death of Adriaen, aged 35, in January 1672, and the unhappy state of Willem van de Velde I's marriage (from his own infidelity). They probably arrived in England early in 1673 – though Willem van de Velde II's last child was baptised in Amsterdam in 1674, when his father also returned to collect his wife Judick (Judith), on their reconciliation.

It was an astute move. The three entirely naval wars that England fought against the Dutch Republic during 1652–1674 – for dominance as northern Europe's main sea-trading nation – laid the foundations of the British colonial empire, at Dutch expense. The Royal Navy thereafter generally advanced under the late Stuart monarchy: both Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York (later James VII & II), both understood the political and commercial potentials of sea power.

James served as Lord High Admiral for his brother to 1673 – when debarred from office as an open Roman Catholic – and was a bravely effective fleet commander in the Second and Third Dutch Wars (1665–1667 and 1672–1674). Henri Gascars' dramatic full-length of him dressed as Mars, god of war, well suggests his self-image in these roles. It is also interesting on other counts since Gascars was a French artist who worked for the Catholic clique in the Stuart court, mainly painting women, and it is the only major male oil portrait by him in UK public hands.

Both Charles and James were also keen yachtsmen, as a pastime that – with a taste for Netherlandish marine painting – they had acquired in Dutch exile during England's experiment with Puritanical republicanism, after Parliament executed their father Charles I in 1649.

When Charles II was recalled to the throne in 1660, the Dutch sent him home with the yacht Mary as a diplomatic gift, and English ones were soon being built in the home dockyards for royal and other naval use. Much that we know of the Stuart yachts today is from paintings done by the Van de Veldes after their move to England.

The English Yacht 'Portsmouth' at Anchor

1675

Willem van de Velde I (1611–1693)

Willem the elder's view of a relatively plain one, the Portsmouth of 1674, is a good example of his style in such subjects. Unusually, it and two other similar ship-portraits by him (all in the Greenwich Hospital Collection at the National Maritime Museum) are on wooden panels since they were painted to decorate the cabin of another yacht, the Charlotte of 1677, and are rare surviving salvage from when it was broken up: much other similar work, by various artists, is no doubt long lost.

On 12th January 1674, Charles II formally granted each Willem a retainer of £100 a year, the father 'for taking and making Draughts of seafights, and the like Salary…unto Willem van de Velde the Younger for putting the said Draughts into Colours for our particular use.'

He also gave them studio space in the Queen's House at Greenwich, which was completed in about 1635 and by 1670 was in royal 'grace-and-favour' use: others whom Charles II gave lodgings there around the same time included one of his mistresses, the refugee French Huguenot traveller and court jeweller Sir John (Jean) Chardin, and, in 1675/1676, his first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, to oversee the building of the Royal Observatory on the hill above.

'The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea'

Showing works by Willem van de Velde the II, Peter Lely and Godfrey Kneller in the East Bridge Room of the Queen's House

Today, the Queen's House displays the art collections of the National Maritime Museum as one of the Royal Museums Greenwich sites, always including paintings by the Van de Veldes but currently (to 14th January 2024) in a substantial exhibition, focusing mainly on their 'English-period' work, to mark the 350th anniversary of their arrival.

Charles II's grant was not just a personal favour to them: in effect, it also launched 'marine painting' as a distinct artistic form in Britain. This, in turn, was also one of the reasons why the Queen's House, as its point of origin, became part of the National Maritime Museum on its official foundation in 1934.

Apart from the 1674 payment warrant, evidence of the Van de Veldes' installation and early work at Greenwich is circumstantial. The earliest is a further order that year for them to be allowed space 'above stairs' in the House to lay out designs for a series of large tapestries depicting English naval successes against the Dutch, followed in 1675 for blinds to be supplied in their ground-floor painting room, which was the south-west parlour overlooking Greenwich Park.

The Burning of the Royal James at the Battle of Solebay, 28th May 1672

after 1684, tapestry by Thomas Poyntz after Willem van de Velde I (1610/1611–1693)

These first tapestry subjects, with others later, were a set of six of the Battle of Solebay in June 1672, which Willem the elder had witnessed and drawn from the Dutch side. Five are still in the Royal Collection and one at Greenwich: two from another incomplete set are in Amsterdam and three in Philadelphia.

One of the earliest identifiable large paintings done in the Queen's House – apparently in the expectation that either Charles or James would buy it, though neither did – was of both the royal brothers visiting the fleet in the Thames following the battle, where James had been in overall command.

A Royal Visit to the Fleet in the Thames Estuary, 1672

1696

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

In the painting, Charles is going aboard James's flagship Prince by boat from the yacht Cleveland at centre left, probably with the yacht Katherine to its left.

James seems to have taken a direct interest in the complex business of composing the Solebay tapestries and views of other sea actions, at which neither of the Van de Veldes were present in their English period. They did this both by amassing a large reference stock of detailed drawings of the ships involved and eyewitness statements of how events unfolded. Both could then be translated into working studies to satisfy both the accuracy and status requirements of knowledgeable seafaring patrons and participants.

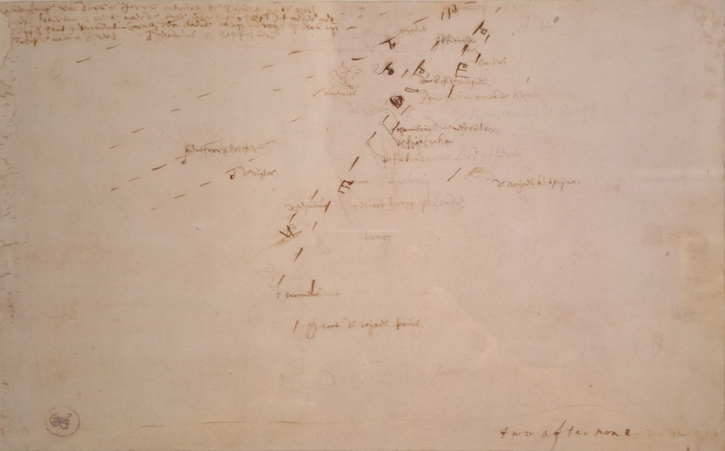

A rough sketch-plan of the Solebay action in the Boymans Museum, Rotterdam (but also on loan in the current exhibition) is largely by James: Willem the elder added ship names to it in discussion with him and a note identifying a timing phrase of 'two [in the] afterno[o]ne' as the Duke's handwriting.

Sketch plan of the Battle of Solebay (1672) by Willem van de Velde I

Over 2,500 drawings by father and son are still known, about 1,450 of them at Greenwich. Many relate to paintings of which there are also often several versions largely or wholly by studio assistants (most not firmly identified).

The Battle of the Texel (Kijkduin), 11th–21st August 1673

1673 (?), drawing by Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

The Battle of the Texel, 11–21 August 1673

late 17th C–early 18th C

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

The drawing shown here is one of at least two similar known elsewhere, and the related painting is one of three different Van de Velde oil versions at Greenwich alone.

The overall recorded number of surviving Van de Velde drawings is many more than for other individual artists of the period. Since they also cover all aspects of the studio's output – battles, calms, storms, wrecks, shore life, scenes of peace and commerce, and some instructional examples as well – the total provides a rare window on general working practice at the time.

The current exhibition at the Queen's House includes a broad selection of all sorts, grouped to show how they fit together and were used, including both reproductions and original oil paintings in a reconstruction of the Van de Velde studio – in the room that it once occupied.

'The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea'

Reconstruction of the Van de Velde studio. The small painting on the easel is by Willem the younger's son, Cornelis

When Charles II died in 1685, James succeeded to the throne for just three years until forcibly replaced in the 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688 by his Protestant elder daughter, Mary, and her Dutch husband, Willem of Orange, as Britain's only modern 'joint monarchs', Mary II and William III.

The new Dutch king did not greatly favour the Van de Veldes – probably as too associated with his authoritarian Roman Catholic father-in-law – but they continued to prosper as leaders of the English marine school that was developing around them as exemplars, and to do official work.

Willem the younger, for example, went profitably with Admiral Russell's fleet to the Mediterranean in 1694–1695.

An Action between English Ships and Barbary Corsairs

c.1695

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

Although he had painted largely imagined British actions against the 'Barbary pirates' of the north-African coast before he went there, that shown here probably dates to just afterwards. The terrifying shipwreck (below) of a slightly indeterminate form of Mediterranean vessel with a lateen mainsail, was probably also painted around 1700, as a result of his expedition.

A Mediterranean Brigantine Drifting onto a Rocky Coast in a Storm

c.1700

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

Willem van de Velde II also maintained ties with Greenwich to late in life (and by one report died there) but he and his father probably lost use of the Queen's House when, apparently in 1693, they left the longstanding family home in nearby East Lane (today Feathers Place and Eastney Street) and moved to Sackville Street, St James's in London. Willem the elder died there that December but the studio continued to flourish under Willem the younger until his death in April 1707 (by then in the reign of Mary's sister, Queen Anne), and for some years after that under his son Cornelis (c.1675–1714), also a fine marine painter in his father's manner.

The English Ship 'Royal Sovereign' with a Royal Yacht in a Light Air

1703

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

Willem the younger's last great ship portrait was of the Royal Sovereign in 1703, probably made when Queen Anne's husband and Lord High Admiral, Prince George of Denmark was on board.

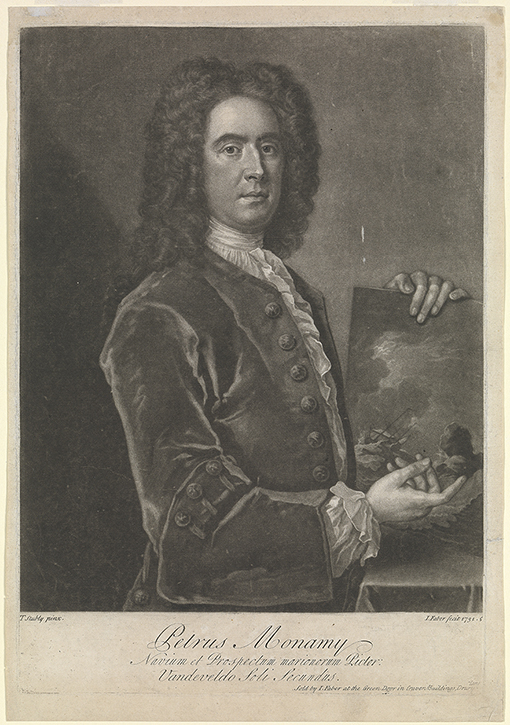

Peter Monamy

1731, print by Johan Faber II (1684–1756) after Thomas Stubly

Following on from him, Peter Monamy (1681–1749) was the leading first-generation English marine painter and, among other things, painted several slightly variant copies of Van de Velde II's Royal Sovereign, the most impressive of which he presented to the Painter-Stainers' Company in 1726. The Latin inscription on this portrait print calls him 'second only to van de Velde' and shows a very 'van-de-Velde' storm scene of his own.

Samuel Scott

c.1731–1733, print by Johan Faber II (1684–1756) after Thomas Hudson (1701–1779)

Samuel Scott (1701/1702–1772) succeeded Monamy as the leading English-born marine painter of the mid-eighteenth century, though he is also known for his London scenes. Here he also acknowledges his debt to Van de Velde II by holding a stern-view portrait of an anchored flagship, based (in reverse) on the latter's 1703 painting of the Royal Sovereign.

English Ships at Sea Beating to Windward in a Gale

c.1690

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

Between Monamy and Scott, the short-lived Charles Brooking (1723–1759) was an even more talented and atmospheric painter but – probably due to an artisan background and lack of their business skills – died in poverty. In some cases, his admiration for Willem van de Velde II shows in just copying the latter's composition while updating the shipping in it to early eighteenth-century form.

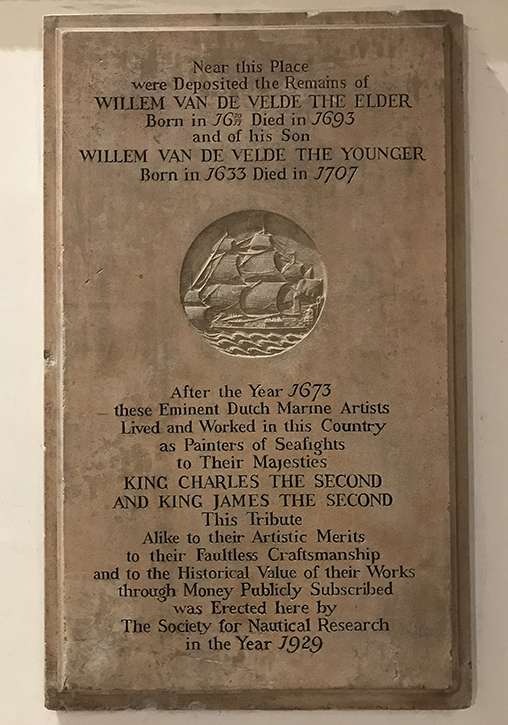

The Van de Velde memorial tablet in St James's Church, Piccadilly

Both the Willems, father and son, were buried at St James's, Piccadilly: their graves are long lost but a monument to them, placed by the Society for Nautical Research in 1929, is still easily seen there just inside the west door.

Pieter van der Merwe, Group Leader of Art Detective's Maritime Subjects

'The Van de Veldes: Greenwich, Art and the Sea' is free to visit at the Queen's House, Greenwich. It ends on 14th January 2024 but a selection of the artists' artworks, with other seventeenth-century paintings and portraits, is always on display