In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

'I believe it's incumbent on all artists who make work about the lived experiences of other people to reflect on their own intentions and ethics,' says Anthony Luvera. The Australian-born photographer, who lives and works in the UK, has a collaborative practice based around creating assisted self-portraits that give agency to his subjects. In an extensive body of work created with people experiencing homelessness, he has honed a distinct methodology that has brought social issues to the fore and had a lasting impact on several participants.

Installation of 'Construct' by Anthony Luvera

Snow Hill Square, Birmingham, 14th September to 13th October 2022

His latest work, Construct, is currently on public display in Snow Hill Square, Birmingham and Snow Hill Station (until 13th October 2022). It features 21 new assisted self-portraits created in collaboration with people who have experienced homelessness in the city. Commissioned by GRAIN Projects, it has been produced over the past four years and seen Luvera work with SIFA Fireside, Birmingham's main day centre for homeless and vulnerably housed adults.

Installation of 'Construct' by Anthony Luvera

Snow Hill Square, Birmingham, 14th September to 13th October 2022

His body of work frames its subjects in the way they wish to be represented. The self-portraits command you to look these individual photographers in the eye, bringing their personality and experiences to the fore. It challenges our preconceptions of people experiencing homelessness and forces us to consider our personal response to one of society's most vulnerable groups.

Installation of 'Construct' by Anthony Luvera

Snow Hill Square, Birmingham, 14th September to 13th October 2022

Gemma Briggs, Art UK: You're described as a socially engaged artist. Can you tell us what this means and why your practice developed in this way?

Anthony Luvera: As a photographer, I've always been interested in the ethics of representation. In 2002 I was invited by the homelessness charity Crisis to make photographs at Crisis at Christmas. It was assumed that I would go in and take pictures in a traditional point-and-shoot way. I felt very uncomfortable about that. I was being a bit of a smart Alec and said I'd prefer to see what the people I met would take pictures of, and I left it at that.

A few months later I was doing some consultation for Kodak and found myself able to access many disposable cameras and processing vouchers. That conversation was bouncing around in my mind so I went back to Crisis and proposed to set up a photography workshop where I would invite people experiencing homelessness to photograph the things they were interested in.

I volunteered at the following Crisis at Christmas and did all the things that volunteers do: organised a karaoke session, helped people with computers, helped in the kitchen. When it seemed appropriate, I gave people a little piece of paper that said, 'if you're interested in photography, come and see Anthony on Friday afternoons between 2pm and 5pm at Crisis Skylight in Spitalfields'. I kept my expectations for attendance really low. I thought if a handful of people could come along then great.

Actually, at that very first session over 90 people arrived – and with many questions. What are you doing this for? Who's going to benefit? What will I get out of this? Will I make money out of this? Will you make money out of this? These questions really struck at the heart of the ethics of representation. I answered as honestly and openly as I could: I didn't know what I'd be doing with the pictures. At that point, I was just really intrigued to see what the person traditionally seen as a subject would choose to represent.

Documentation of the making of 'Assisted Self-Portrait of Ben Rodda'

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

That was the beginning of my work as a socially engaged artist. Since then, in towns and cities around the country, including Belfast, Colchester, Brighton, Coventry, Birmingham, Manchester and all over London, I've continued to work with people experiencing homelessness.

Gemma: You have formulated a very specific process in response to your aim of giving agency to the participant. Can you talk us through the technique of assisted self-portraits and why documenting the process forms part of your body of work?

Anthony: I developed the methodology of creating a portrait of the participant, but without photographing them myself. The idea is that I invite the participant to take me to a place that's significant to them, where I teach them how to use professional camera equipment on a tripod, with a laptop, a handheld flash and a handheld cable release. We do this as many times as we're able to, and then the final image is edited or selected by the participant.

Documentation of the making of 'Assisted Self-Portrait of Kevin Spachier'

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

My intention with the assisted self-portraits, as I call this method, is that the person in the picture feels able to present a version of themselves they feel most comfortable with. In many respects, the process of my practice is as important as the finished images or other artefacts that circulate as the project.

Documentation of the making of 'Assisted Self-Portrait of Sahai Dejonge'

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

I've made projects with people experiencing homelessness, people who identify as LGBTQI+, people from lower socioeconomic households, and other marginalised individuals and community groups. I'm always keen to find ways to represent the process of making the work. In doing so, I'm aware that often the telling of the process is filtered through the singular voice of the artist, becoming subject to the problems of representation the work is trying to tackle in the first place.

So, for example, on some projects I have co-created a blog where participants can report their thoughts about taking part. I believe the role of documentation is incredibly important to a socially engaged practice, because it can underscore the social dynamic upon which the work is founded.

Gemma: Your projects begin with months, even years, of volunteering to meet potential participants and then goes to a very personal place with them. What is your experience of working so closely with your collaborators?

Anthony: I've always said that my practice is not about making images, it's about developing relationships. For Construct, I spent the first year of this four-year project volunteering in SIFA Fireside, the main day centre for people experiencing homelessness or who are vulnerably housed in Birmingham. I helped in the kitchen to prepare breakfast and lunch, and to serve meals. I spent time getting to know the staff and the clients of the service. That period of time was spent without using any photography or any kind of recording equipment.

This is quite typical of how I work. I like to spend as long a time as possible establishing relationships with the staff and getting to know about the ways in which the organisation works. This time is also an important way for me to get to know the clients of the service. To see if they would be interested in participating in my work and to ask them questions such as, should I even be doing this at all? If so, how should I go about it? I feel so honoured to be offered the opportunity by participants to be invited into their lives, to hear the stories about their experiences and their hopes for the future, and, also, their thoughts about photography and representation. My role is to enable people to explore photography; that's what it comes back to.

Documentation of the making of 'Assisted Self-Portrait of Kevin Spachier'

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

Gemma: It's a very different approach than that of a photographer walking down the street, snapping a picture of a person experiencing homelessness and posting it on social media without their consent. How important is it for you to form partnerships with those supporting services such as SIFA Fireside or Crisis?

Anthony: It's really important. I want to be certain that the people that I meet and invite to take part in my work are supported in the areas of their lives they require assistance with. I'm not a social worker, I'm not a housing advisor. What I can do is invite people to take part in my work to explore their interests and the representation of the experience of homelessness.

Assisted Self-Portrait of Ben Rodda

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

Gemma: It's interesting that you choose to display and disseminate your work in public spaces, how important is this to your practice?

Anthony: I'm always keen to show my work in the public realm.

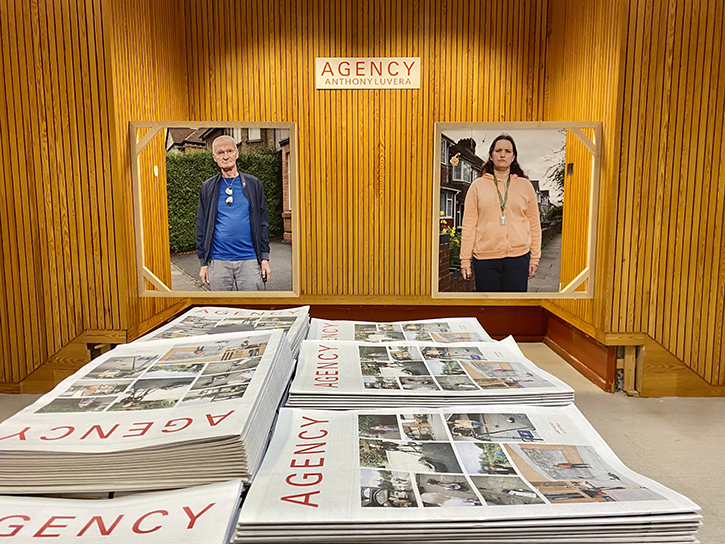

Installation of 'Agency' by Anthony Luvera

Warwick Row, Coventry, Coventry UK City of Culture 2021, 8th to 28th October 2021

That isn't to say that I haven't worked with museums and galleries, but working in the public realm offers the chance of reaching audiences in an unexpected way, enabling people to engage with the work who perhaps wouldn't choose to go into a museum or gallery. Also, many more people will pass through a public square and spend time with the work than would go to visit an exhibition in a gallery.

Installation of 'Construct' by Anthony Luvera

Snow Hill Square, Birmingham, 14th September to 13th October 2022

Over the years, I've shown my work on the London Underground, on billboards and fly posters, in outdoor spaces at public festivals. I do also regularly show work in galleries. For example, Frequently Asked Questions was displayed at Tate Liverpool as part of a programme developed by the Museum of Homelessness.

Installation of 'Frequently Asked Questions' by Anthony Luvera

State of the Nation with Museum of Homelessness, Tate Liverpool, 22nd to 28th January 2018

Installation of 'Frequently Asked Questions' by Anthony Luvera

State of the Nation with Museum of Homelessness, Tate Liverpool, 22nd to 28th January 2018

Whether in a museum or gallery or in the public realm, I'm keen to ensure that the work incorporates a public engagement programme to activate conversations with different groups of people and facilitate a dialogue. With Construct I'll be facilitating a long table event in Birmingham on 10th October 2022, which is World Homeless Day, involving speakers from organisations such as Shelter, Birmingham City Council, Mayday Trust and the Museum of Homelessness, as well as people with lived experience of homelessness.

Gemma: What are your hopes when you begin a new collaborative project?

Anthony: With my work about homelessness, in particular, the point is to shake up preconceptions and to draw attention to the fact that homelessness is a political choice which is shaped by the decisions made by people in positions of power. If the work can inform a school child's understanding of homelessness or inform someone who works in the housing department of a local authority to think again about how they work with individuals experiencing homelessness, then that is the purpose of the work.

Assisted Self-Portrait of Jas Jangha

from 'Construct' (2018–2022) by Anthony Luvera

Engaging people in positions of power at local and national government level is a big part of my practice. Frequently Asked Questions led to Gerald Mclaverty, my collaborator on this project, and I being invited to the Houses of Parliament to present to members of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness. For someone with experience of homelessness to go into the very seat of power in this nation and sit across from the table with people who are shaping the agenda on issues that affect his life felt like a meaningful moment and the appropriate place for the work to be aired.

Gemma: Are there particular projects where the experience of working with the group of participants has had a lasting impact on you?

Anthony: Sometimes the relationship with a participant will fade away. At other times, participants and I remain in contact on a regular basis, including some of the very first people I worked with back in 2002 in London. One example of this is Phillip Robinson, who volunteered to work with me for about a year and a half when I was first developing the method of making assisted self-portraits. I'm still very much in contact with him, and he is now housed and has established a photographic practice.

Installation view of 'Agency' by Anthony Luvera

Fotogalleri Vasli Souza, Oslo Negative, Oslo, Norway, 23rd September to 16th October 2022

Another participant who took part in early workshops at Crisis now runs the workshop and works as a photographer. The participants of Agency, which was commissioned by Coventry City of Culture, have self-organised as a collective called the Agency Photography Group. I've been working to support them in the making of an exhibition which launches in October.

Installation view of 'Agency' by Anthony Luvera

Fotogalleri Vasli Souza, Oslo Negative, Oslo, Norway, 23rd September to 16th October 2022

I think people take part in my work for many different reasons. For some people, it's about having the opportunity to access a camera to make photographs for their own personal use, which are never used in exhibitions or publication. For other people, it's an opportunity to explore their interest in photography which they have not previously had the chance to develop. I'm happy to facilitate any participant's intention for taking part.

Gemma Briggs, Head of Marketing and Communications at Art UK

'Construct' by Anthony Luvera is on display at Snow Hill Square, Birmingham, until 13th October 2022

You can book free tickets to the Long Table Discussion on 10th October 2022