Without wishing to spoil the plot of Robert Browning's verse drama Pippa Passes (1841), you could certainly say that Pippa passes many strange and disruptive things. Whilst Browning's eponymous heroine wanders through the town on her one day off, she saunters obliviously past a murder plot, a would-be assassin and a scheme to ruin her. Accidental it may be, but Pippa has her own disruptive power too – the sound of her song turns every plan on its head, tweaking various villainous lives into new shapes.

But at no point in Browning's work does Pippa pass foot-by-feather with an unruly gaggle of geese. For this chaotic development, all credit must go to Elizabeth Siddal, and her pictorial reimagining of Pippa's startlingly consequential stroll.

You may know Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862) as a Pre-Raphaelite artist-poet, whose work embraces medievalist aesthetics and reinvents balladic stories – who broke from her overbearing patron John Ruskin when he tried to stop her painting ghosts, like her 1856 watercolour The Haunted Wood – who regarded mid-Victorian artistic norms as a negligible part of her creative practice. You may encounter her art in an increasing number of exhibitions (including 'The Rossettis', on now at Tate Britain) and her poetry in Serena Trowbridge's 2018 edition My Ladys Soul. You may even have noticed the relentless mythologising around her life, art, face, grave, hair, husband – the stuff of countless fictions and fantasies.

But you might not know about the proliferation of geese in her 1854 pen-and-ink drawings. Permit me, if you will, to introduce you.

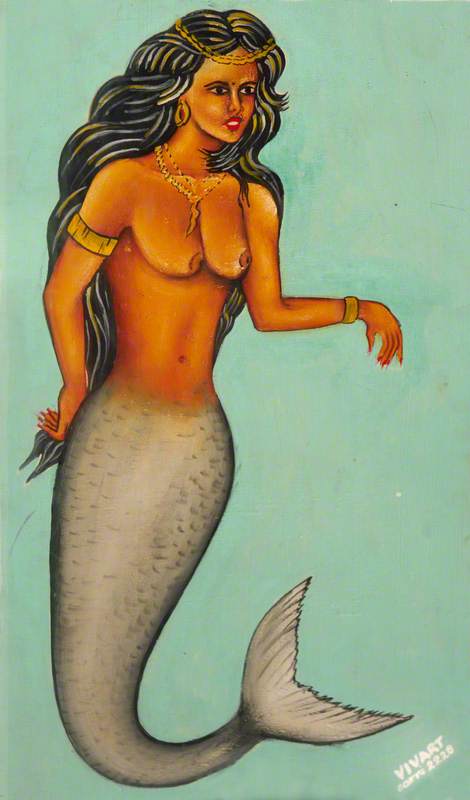

Siddal's Pippa Passes depicts a moment from Browning's drama – in which, for once, Pippa pays attention to whom she passes. Unlike most characters, the 'poor girls' on the steps talk to Pippa directly, luring her over with a love song, as part of a complicated plan to stop her claiming an inheritance she doesn't know about. Prior to Pippa's approach, the girls have been chatting about their own broken inheritances, grand wishes and sexual conquests – the drawing's alternate title, Pippa Passing the Loose Women, draws much attention to the latter. Their call to Pippa throbs with the same erotic energy: 'Oh, you may / come closer – we shall not eat you!'

Siddal's drawing transforms the girls' song into saucy gestures: their fingers clasp the steps, caress each other's bare skin, or point in a perfect diagonal to Pippa's crotch (where the branch in Pippa's hand stands very much to attention). But the drawing also partakes in the disruptive spirit of Browning's plot, by unsettling its source material with new additions – namely, the three geese who cluster around Pippa's branch, chivvying her towards the girls with their beaks and their snapping shadows.

Geese make sense for the subject. Southwark, Siddal's neighbourhood, was historically home to sex workers known as the Winchester Geese. One of them – 'Nan the potter' – immortalised these 'geese' on a ceramic dish, now in the Museum of Sex Objects.

Pippa's geese also speak to the queerness of the depicted scene. In Browning's drama, the sapphic eroticism is more-or-less contained within the flimsy framework of an absentee man and an insidious scheme, but both man and scheme are simply absent from the drawing, which foregrounds instead women ogling women.

Chaos in the village

screenshot from 2019's 'Untitled Goose Game'

How appropriate, then, that the goose is currently something of a queer and trans icon, as brilliantly articulated in Daniel Lavery's essay 'I Am The Horrible Goose That Lives In The Town'. The essay is a queer response to the award-winning video game Untitled Goose Game (2019), which uses the game's premise (playing a goose disrupting village life) to explore how being 'the most goose who ever was' has the power to unsettle dominant social orthodoxies, to 'make a puzzle of your garden', 'make every escape' and 'undo all of your doing'. Read in this presentist light, we can think about Pippa's geese as embracing their capacity for chaos, enabling and encouraging the scandalous sapphic looks between the ambling ingenue and the 'loose women'.

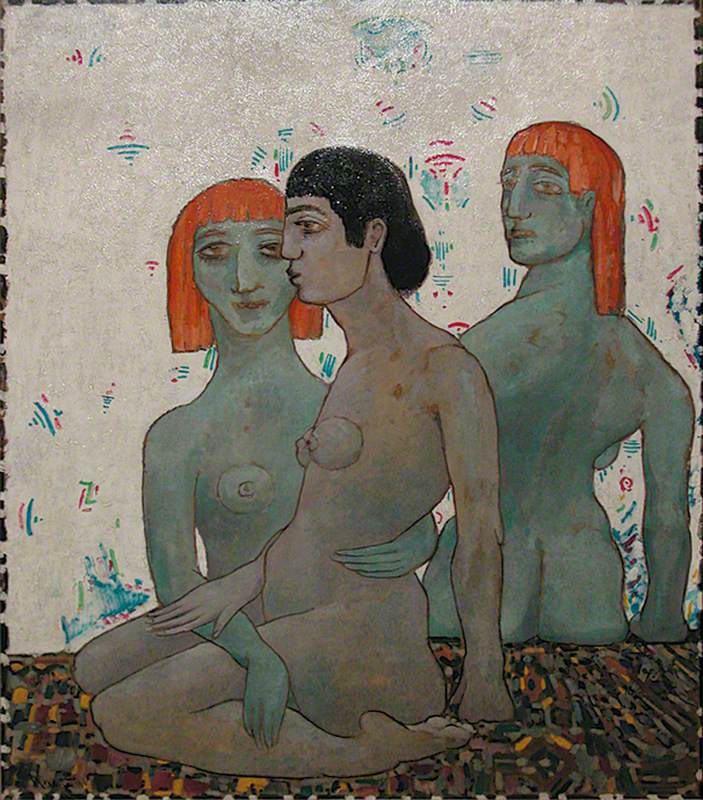

In the same year as Pippa Passes, Siddal produced one of her most enigmatic compositions, the posthumously titled Lovers Listening to Music. In this drawing, two Black musicians play for a white audience: a woman, man and eerie child. Though the figures seem segregated into pairs, their looks and gestures disrupt a neat heterosexual arrangement – again, with another diagonal encounter. Like the woman on the right in Pippa Passes, the musician in the stripes gestures provocatively to the white woman whilst the man looks away, setting her fingers to purpose on the instrument and on herself, as the white woman brushes her lips to her own fingers and points them at her crotch.

It's an encounter which needs careful discussion – of its intersections with the harmful trope of the over-sexualised Black woman, of the double standard in the women's gazes – and in my PhD, I'm indebted to Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019) as a framework for thinking about it in all its complexity. But for our purposes here, it's also worth noting that – whilst this fingering dominates the foreground – there's something weird in the fields behind…

A wild goose chase.

Squint for it. There's a tiny goose (seen from the back: all neck, beak, tail-feathers and webbed feet) pursuing a stick-person across the landscape. Except that, considering the drawing's perspective, the goose isn't tiny – it's the same size as its quarry, which actually makes it quite large. You could, of course, take the easy way out of this goose-based conundrum and blame it on the artist-poet's technique – which, when considered beside normative Victorian ideals of sizing and perspective, is all too often dismissed as inept. Or you could stop reading Siddal's work on terms to which it doesn't subscribe, and discover another disruptive goose, one which partakes of the whole landscape's refusal to fit expected divisions of space, and resonates with the queer disruption of heterosexual segregation playing out in the figures' interactions.

And, speaking of divisions of space, you may also notice that the goose is outside the enclosed garden with the crested gate, just like its predecessor in the anti-enclosure folk poem decrying the privatisation of common land: 'Who steals the common from the goose?' Or, as Lavery's horrible goose puts it a few centuries later – 'I don't agree with property and never have'. When you notice Siddal's disruptive geese, these connections appear – I'm barely scratching the surface of the conversations these birds could provoke.

So what might the geese encourage us to do, as viewers of Siddal's much-maligned art? Well. These drawings are so often seen through a cisheteronormative lens, which presents Pippa and the girls as two sides of a pure/impure woman binary, or romanticises Lovers Listening to Music as a homage to a straight white couple. But we can make space for other readings too – readings which, inspired by 1854's gaggle of geese, delve into the works' queer disruptions and diagonals.

It's vital that queer readings of historical creative work are part of our ongoing discussions about engaging with the past – and queer reading Siddal's work certainly showed me fascinating new possibilities, of interpretation and how interpretations can be made. In the spirit of embracing these possibilities, then, I'll end with Lavery's demand:

'Everybody be awake to the goose now and from now on!'

Nat Reeve, writer and researcher