The Scottish painter Edward Baird was a private man whose career was limited by chronic ill health, and who spent the majority of his life living with his mother in the small harbour town of Montrose in Angus.

He avoided publicity, and left behind only a few dozen paintings, but in these highly individual works are clues that can help us build a picture of the artist who created them.

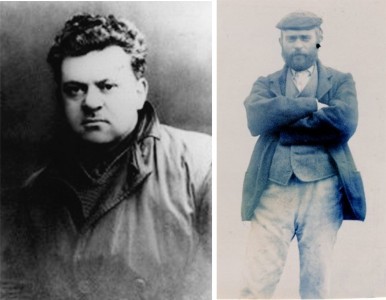

Baird studied at Glasgow School of Art alongside other talented painters such as James McIntosh Patrick, and in 1927 was awarded the Newbery Medal as the best student of his year.

During his early career, he exhibited widely, including at the Royal Academy and the Royal Scottish Academy, but his output was hampered by very slow working methods and crippling perfectionism.

After a travelling scholarship to Italy between December 1928 and March 1929, he moved back to Montrose, the town of his birth.

In the inter-war years, Montrose had a surprisingly rich cultural scene; it was home to the sculptor William Lamb, the architect George Fairweather and the nationalist writers Hugh MacDiarmid and Fionn MacColla.

MacDiarmid, alongside figures such as Edwin Muir and Violet Jacob, called for a 'Scottish Renaissance', which would put an end to art that romanticised Scottish rural life.

Baird was deeply attracted to these ideals – for much of his life, he would be involved in promoting cultural activities in Montrose, and painting portraits of the many friends he made at exhibitions and political gatherings in the town.

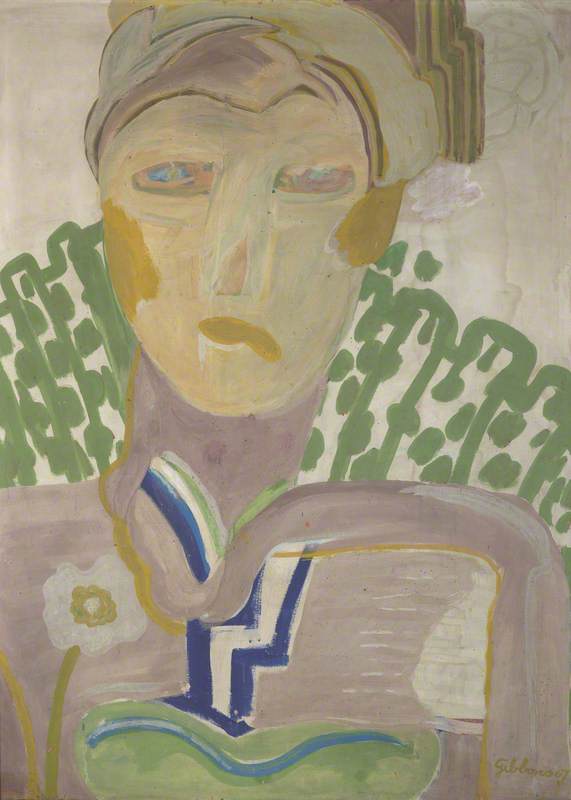

Fionn MacColla (1906–1975)

(Portrait of a Young Scotsman) 1932

Edward Baird (1904–1949)

In these portraits, Baird can be seen to be representing the life and landscape of the Scottish Lowlands with realism and modesty, in line with his Scottish Renaissance beliefs. His portrait of MacColla was exhibited to warm reviews in both Edinburgh and London in 1932.

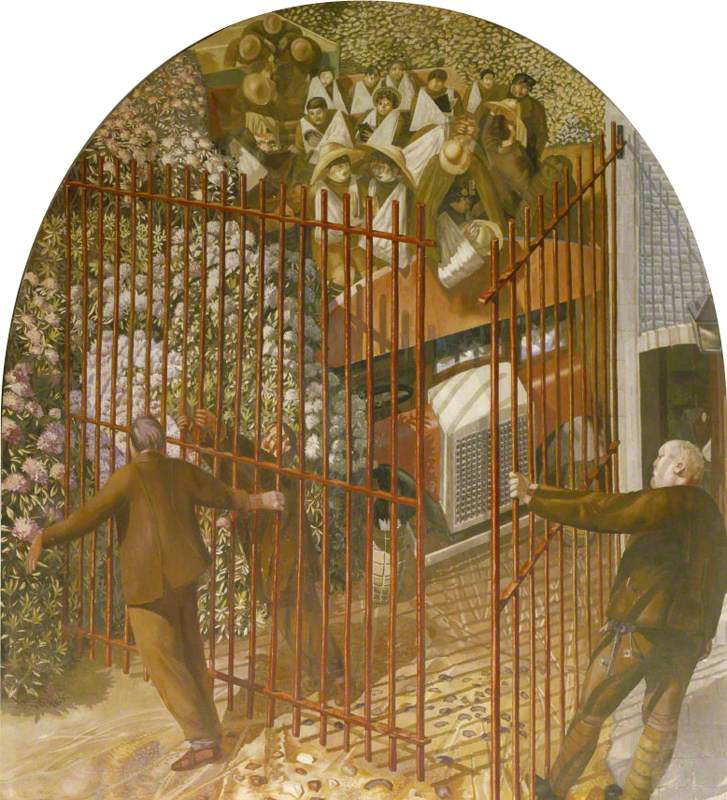

His 1935 portrait of his close friend George Fairweather shows the development of a painterly precision that was to become the hallmark of Baird's mature work, and features an unusual arrangement of objects in the foreground, which anticipates some of his later compositions.

George Fairweather (1906–1986), Architect

1935

Edward Baird (1904–1949)

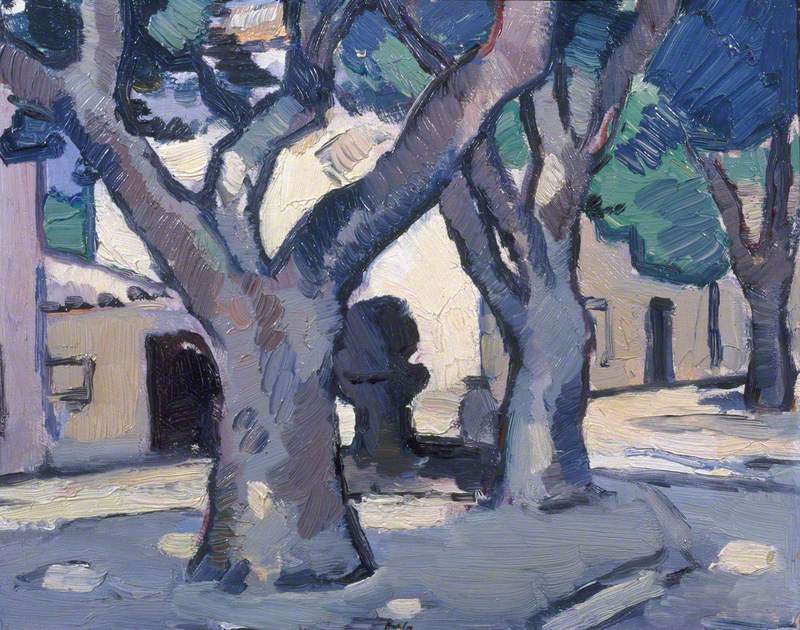

He may have only rarely travelled abroad, and in his writings he was critical of modernist painting, but the pictures of the 1930s hint that – like many of the Scottish artists around him – Baird was taking inspiration from the Continent.

His older contemporary James Cowie, who was working in nearby Arbroath, had long experimented with curious still life arrangements, often set in front of more traditional landscape views.

Baird went one step further, painting several striking works inspired by Surrealist ideas, such as The Birth of Venus, where his future wife Ann Fairweather stands nude on a Montrose beach, swamped by an assemblage of objects in the foreground.

Baird was known to work from reference photographs, and the flattened, harshly modelled appearance of both the objects and the figure here seem to foreshadow the kind of stark, emblematic arrangements made famous in the Pop Art collages of Richard Hamilton decades later.

Whatever the meaning of the work, Baird was proud of the picture and gave it to his old friend James McIntosh Patrick as a wedding gift, and it was likely through McIntosh Patrick that Baird secured a teaching role at Dundee College of Art in 1936. Baird's chronic asthma meant he was often absent from work, and he left the College in 1939.

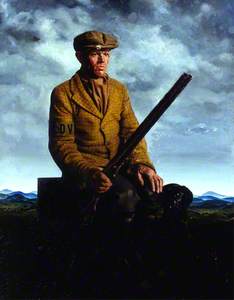

In the autumn of that year, Baird, still fully committed to local subject matter, was working on a portrait of one of his oldest friends, the labourer and poacher James Davidson.

When war was declared in September 1939, Baird wasted no time in adapting this vivid picture, painting a Local Defence Volunteer armband onto Davidson's jacket. Yet this was no invention – Davidson, too old to enlist, had been one of the first in Montrose to volunteer for what became the Home Guard.

Baird's picture, originally titled The Gamekeeper, became an earthy symbol of the Scottish war effort, and the rights to the work – now titled Local Defence Volunteer – were purchased by the Ministry of Information.

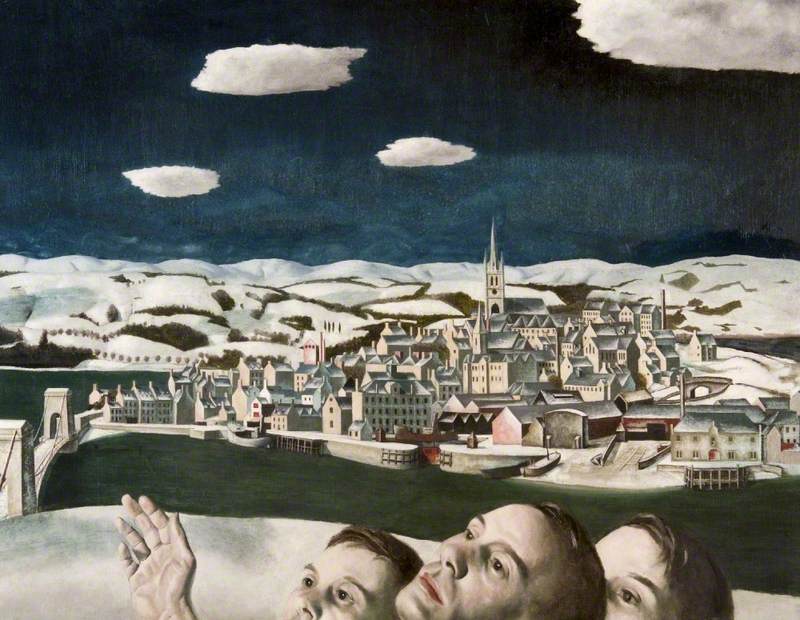

Baird's quiet Surrealism and regionalist tendencies coalesce in his most accomplished and unnerving work, Unidentified Aircraft (over Montrose).

Baird started the painting sometime in 1941, and it hung in London the following year at the exhibition 'Six Scottish Artists', alongside works by William Gillies, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde.

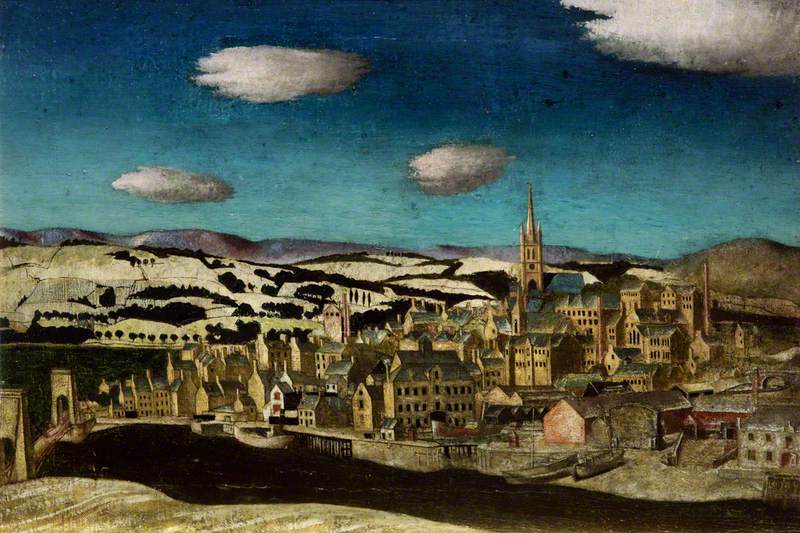

Baird had been working on similar views of his beloved home town since the 1920s, for example Monros, but it was the German air raids on Montrose in October 1940 that inspired him to rework the motif on a theme of war.

In Unidentified Aircraft, we look across the freezing River Esk to Montrose and the winter hills beyond. The town is crowded on a slope and looks fragile in the moonlight, while the night sky above is disrupted by eerie, hovering clouds which resemble patches of floating snow.

In the foreground, a hand is raised and three partially obscured heads are titled to gaze up at the sky, giving the work a quasi-religious feel. The composition originally featured searchlights and aircraft, but as Baird worked towards a final image he took the daring decision to paint these out, creating a remarkable atmosphere of stillness and expectancy as the three blank faces search the emptiness above.

These faces, long thought to be a group of individuals, are actually the same man – a local friend of the artist named Peter Machir, chosen by Baird as representative of all the fearful inhabitants of Montrose. The repetition of Machir's head, on top of the removal of the titular aircraft, not only adds to the air of unreality, but shows how Baird was keen to blend the traditional and the strikingly modern in his work.

While the handling in some elements of the picture, such as the townscape and the hills, calls to mind Renaissance painters such as Pieter Bruegel the elder and Andrea Mantegna, the placement of the heads again betrays the influence of Surrealists working on the continent in the inter-war years.

Unidentified Aircraft is a complex and singular work, which palpably reflects the anxieties of civilian communities during the Second World War, and shows an artist boldly introducing Surrealist elements to a traditional composition almost as a means of defiance and escape. The success of the picture laid the groundwork for Baird to become an official war artist in March 1943.

As Baird's health deteriorated significantly towards the end of the war, he married his long-term partner and sometime model, Ann Fairweather. But he was to live until 1949, embarking on one of his most ambitious canvasses, The Howff, a monumental figure composition based on the Dundee cemetery of the same name, which depicts his wife sitting on a tombstone seemingly coming to grips with her impending widowhood. The painting remained unfinished at the time of Baird's death, on 7th January 1949.

Baird was just 44 when he died, had produced fewer than 40 canvases, and had rarely left the town that he loved. He instructed his wife to burn his paintings after his death, but she held onto them and a retrospective of his work was mounted in Dundee in 1950.

Today his paintings are held in just a handful of Scottish public collections, but looking at those meticulously finished works it is impossible not to think of the people of Montrose and the lives they lead. Baird would surely have been satisfied with that achievement.

Tom Newlands, freelance writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland