The visitor to 'Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940–1970' held in 2023 at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, was greeted by a huge, lyrically abstract painting by Helen Frankenthaler, one of the leading figures in the 'overlooked generation' of women artists who had until recently been excluded from the Abstract Expressionist canon. The exhibition argued that the story of the New York School and its international adherents had, hitherto, been told predominantly through the 'white, male painters whose names are synonymous with the Abstract Expressionist movement'.

Given this contemporary critical indifference it may surprise that more than half a century ago, the one place that some of these artists – and Frankenthaler specifically – were celebrated was Belfast. Indeed, of all regional galleries in the 1960s, the Ulster Museum pursued the most adventurous programme of collecting contemporary art. This was almost entirely due to the return, in 1957, of the art historian Anne Crookshank to her native city, to take up a position as Keeper of Art in the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, soon to become the Ulster Museum.

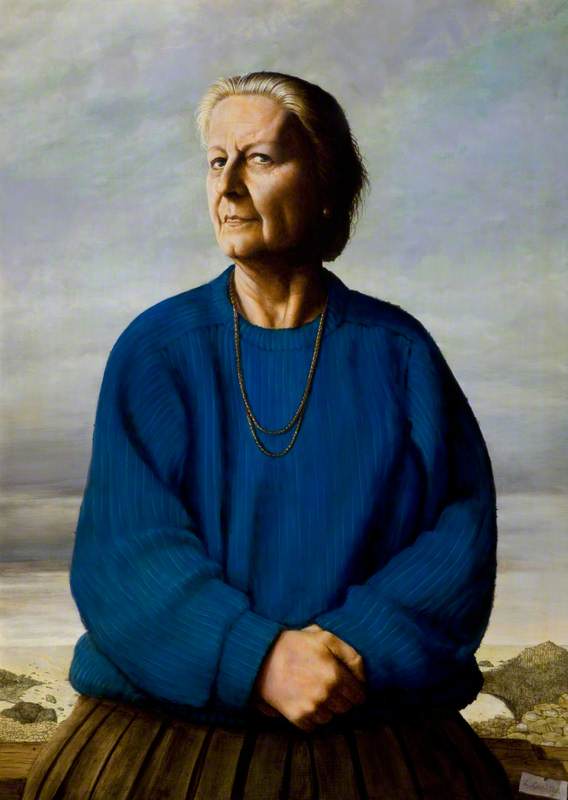

After a childhood in India where her father worked for the Geological Survey, Crookshank studied under Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld Institute and subsequently enjoyed spells working at the Tate Gallery and the Witt Library. In Belfast, Crookshank, in the words of Martyn Anglesea, a later curator at the museum, 'initiated the policy of collecting international contemporary art, against considerable opposition from the powers that then were'.

In many ways, the appointment of a notably feisty young woman – and trained art historian – was a forward-looking move by the authorities, particularly as she succeeded the poet, critic and radical socialist John Hewitt, who took a distinctly regionalist rather than internationalist artistic stance. Crookshank was aged just 30, however, anyone who met her will know that self-confidence was never a quality in which the formidable Miss Crookshank, as she was known, was deficient.

Crookshank later recalled in a brief memoir that as well as an 'extraordinarily varied group of old masters, a Turner, eight very fine Fuseli drawings and one or two Italian and Dutch paintings', she found a 'small collection of English works of the 20s and 30s, [by] artists such as Augustus John and Stanley Spencer, and a few contemporary works by Irish artists'. Other highlights in the museum's collection included the 34 paintings by John Lavery which in 1929 the artist had donated to the city of his birth and other works by Ulster painters, such as John Luke's The Three Dancers (1945), an artist much promoted by Hewitt.

At the time of Crookshank's appointment, the highest sum that the museum had spent on an acquisition was £250 for a watercolour by Peter de Wint. She recalled that she 'sent a report to the committee... pointing out that without regular money and an acquisition policy the museum would never flourish and that good paintings... usually cost more than 250 pounds'.

Harriet Anne (1799–1860), Countess of Belfast

c.1822–1823

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

By good fortune, the year after Crookshank was appointed, a fine full-length portrait of the Countess of Belfast by Thomas Lawrence came on the market. This was just the sort of picture to appeal to her committee and she raised £1,000 to be able to purchase it. (The relative value at the time of a Peter de Wint watercolour and a Thomas Lawrence full-length is staggeringly revealing of vagaries in the economics of taste.)

Before long the museum's annual acquisition budget had grown to £14,000, though this had to be split between several departments, including silver, ceramics, historic costumes and 'a small sum for old masters'. But Crookshank now had a budget to freshen up the collection and she was determined that what Belfast needed was exposure to some of the most advanced international art. Her acquisition policy was carefully thought through. With the crucial help of Ronald Alley – who was, from 1965, the Keeper of the Modern Collection at the Tate Gallery, and the leading British advocate for the New York School – the museum compiled 'a varied list of artists who would show the different shades of modern art'.

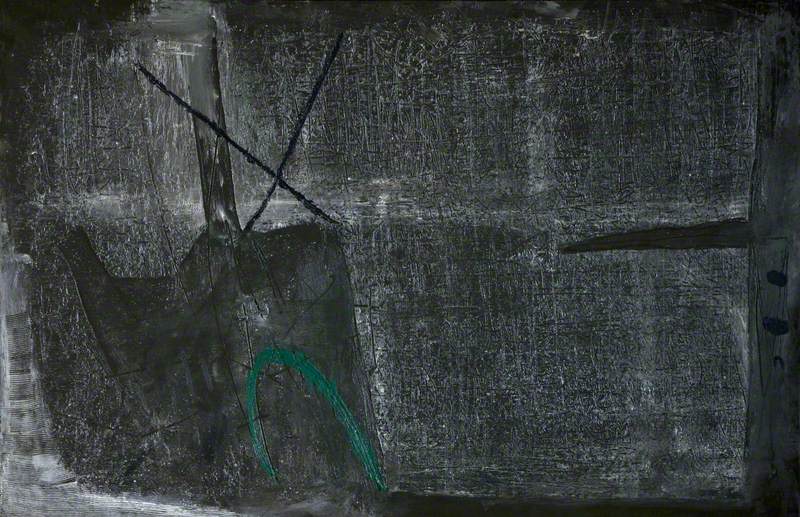

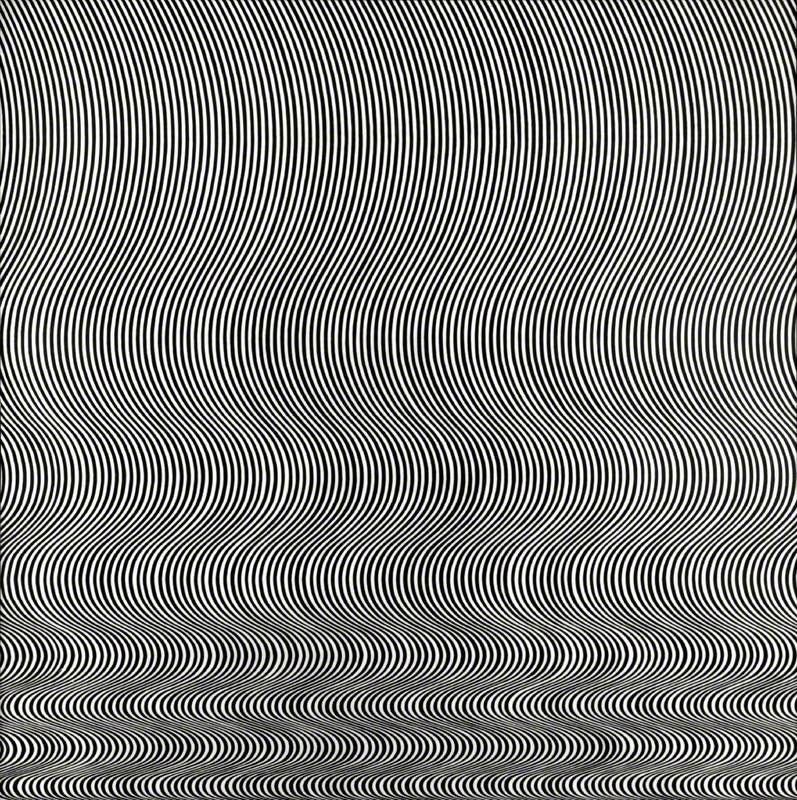

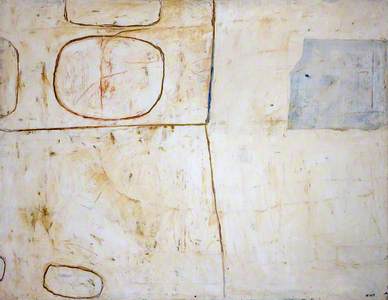

The museum under Crookshank showed admirable even-handedness in seeking out examples of widely divergent art movements, from Op Art and abstraction to art 'Brut' and 'Informel'. Striking purchases included Victor Vasarely's Geta (c.1960–1963), bought from the Hanover Gallery, and Peinture verte (1954) by the Catalan artist Antoni Tàpies.

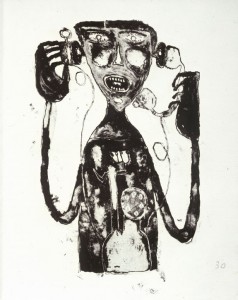

Karel Appel's Portrait of César (1956), a grotesquely mask-like depiction of the Nouveau Réalisme sculptor César Baldaccini, was juxtaposed in the collection with Une place au soleil (1960), a welded iron sculpture by César, an important work from the year after his inclusion in 'New Images of Man' at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. European Expressionism and Existentialism had suddenly landed on the banks of the Lagan.

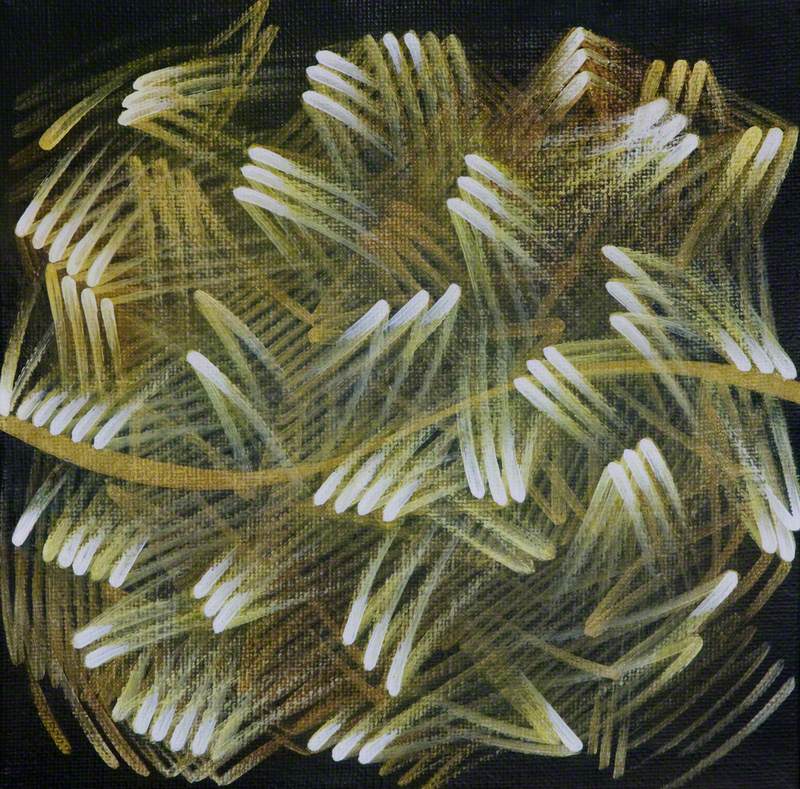

Continuing to explore recent continental trends, in 1965, the last year of her tenure at Belfast, Crookshank acquired Jean Dubuffet's Femme et bébé (1956) in which the eternal theme of mother and child is reimagined, at once as hieratic icon and grinning spectre.

In addition to spending the gallery's meagre funds, Crookshank tapped other sources. In 1959, she facilitated the donation by the Contemporary Art Society of a very significant work by Francis Bacon, Head II (1949).

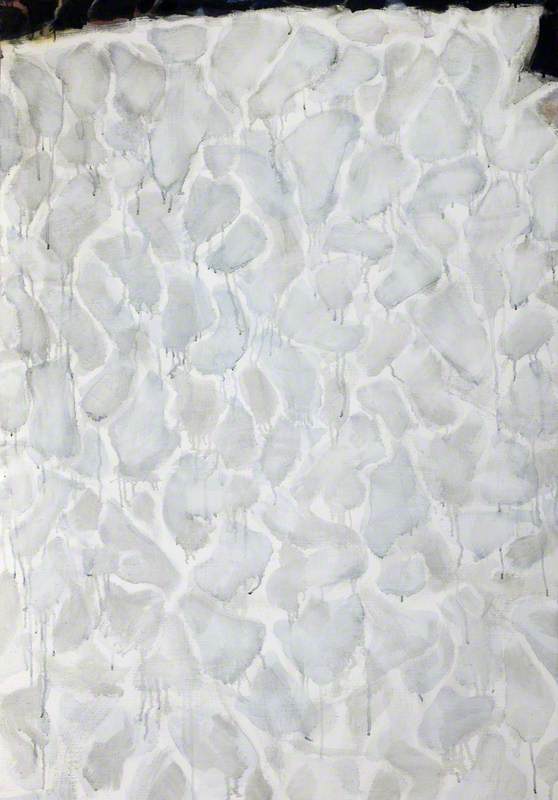

Under Crookshank's guidance, the Ulster Museum did not limit itself to various strands of mid-century European modernism and it was among the earliest institutions in Britain and Ireland to add works of the American Abstract Expressionist and subsequent movements to its collection, purchasing in 1965 the large canvas Sands by Helen Frankenthaler, painted just the year before.

Even after Crookshank had moved to Dublin to set up a history of art department at Trinity College, the museum continued to purchase from the list she had prepared. In 1968 her successor, James Ford Smith, acquired Golden Age (1958) by Morris Louis from the artist's estate through the Waddington Gallery in London, though its price drew hostile commentary. A local paper queried 'Was puzzle picture worth £7,000?' One 'well-dressed woman' said 'she couldn't see any great genius in it.' However an 'Ulsterville Avenue woman' took the more enlightened view that 'It's good to have something to remind us of the modern age we live in'.

If works such as these were often challenging for museums to present to the public and initially caused mixed and often negative reactions, in several instances they have become among the most appreciated and enjoyed aspects of the Ulster Museum's collection. Lest it be thought that Belfast was particularly parochial in its reaction to modern art, it is worth remembering that the outraged – if manufactured – reaction among a metropolitan audience to the Tate's 1972 acquisition of Carl André's Equivalent VIII (the famous 'pile of bricks') at this point lay in the future.

In 1969, the gallery added Grey Space (1950–1951) by Sam Francis to its collection, just the second work by the artist to enter a public collection in the United Kingdom.

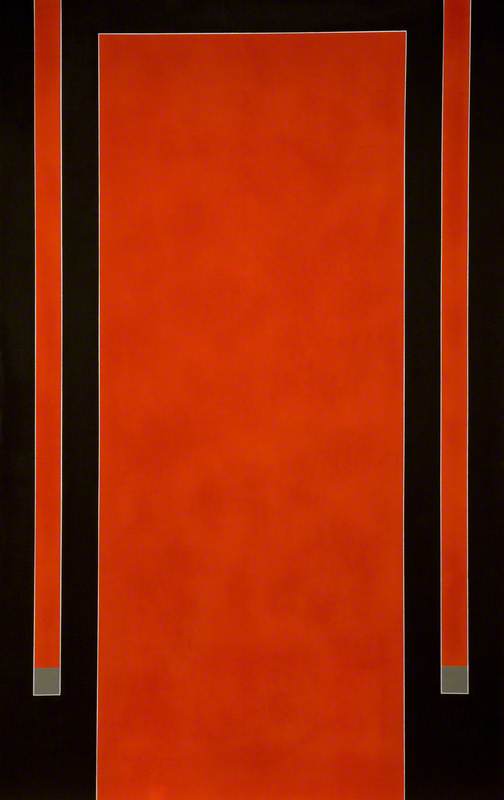

Showing the continuity in acquisition policy during and after Crookshank's tenure, her purchase in 1965 of Kenneth Noland's Newlight (1963) was complemented five years later by the acquisition of the artist's Crystal (1959) as a gift from the artist through the American Federation of Arts. Belfast was in the vanguard of collecting examples of post-painterly abstraction; 1965 also saw Noland enter the Tate's collection for the first time.

Both the Frankenthaler and Nolands were sourced via the Kasmin Gallery, London, which had brought the American Colour Field artists to Europe. There was a local connection, as a partner in the gallery was Sheridan Dufferin, 5th Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, whose home at Clandeboye, near Bangor, County Down, was a centre of artistic life. David Hockney was a frequent visitor – his print Home shows a chair in Clandeboye's library – while Dufferin's sister, Caroline Blackwood, was married for a period to Lucian Freud.

Crookshank was particularly prescient in acquiring works by female Abstract Expressionists, whose importance has only been properly acknowledged in recent years. Her purchase from Gimpel Fils of a work by Joan Mitchell, Painting (1958), was the first example of her art acquired by a UK institution and indeed would remain so for 45 years until Tate acquired a late work in 2009.

It is noteworthy amongst all this purchasing activity that, despite the acquisition during this period of some major works by Irish artists, there was a strongly international focus, and this emphasis was also apparent in the ROSC exhibitions which brought transatlantic and European art to Ireland from 1967 onwards. The first show (for which Crookshank served on the Executive Committee) included work by Appel, Noland, Dubuffet, Vasarely and Sam Francis, all artists whose work had been, or would be, acquired for Belfast. But ROSC controversially excluded Irish artists from its initial shows.

At this date, many Irish artists, even of the most apparently progressive hue, were still producing pastiches of the School of Paris of half a century earlier and it is starkly apparent that contemporary American and European modernism of the sort collected for Belfast had only a gradual impact on local practice, although there were notable exceptions. More broadly in Irish art, Crookshank found echoes of Dubuffet and Tàpies in the art of Camille Souter while Cecil King was one of the few Irish artists to produce a local take on hard-edged abstraction.

But the most obvious exception to this provincialism, William Scott, rather proves the rule, as Scott had imbibed at source the lessons of the New York School on a visit in 1953. Unsurprisingly then, in 1958, in one of her first acquisitions, Crookshank bought for the museum Scott's Brown Still Life. She wrote to the artist in June of that year: 'I... feel it is disgraceful that we have not yet acquired a painting by you and I hope you have heard we are making the necessary preliminaries to do this at the moment.'

It must be said that this situation has been transformed with wonderful holdings of Scott's mesmeric work in the Ulster Museum, where they are a key part of the collection, and also – thanks in part to private munificence – in the Fermanagh County Museum in Enniskillen, where he grew up.

Crookshank's judgment was sure and all of her acquisitions of the art of the 1950s and 1960s have stood the test of time. Remarkably, she was not even a specialist in contemporary art. Her early researches had been on the drawings of George Romney, while eighteenth-century Irish art would subsequently be her primary field of study.

Thanks to Crookshank's carefully considered list, Belfast benefited from joined-up collecting and curating at its best, with many of the key moments in American painting of the 1950s represented by important works showing the move from 'second generation' Abstract Expressionism to Colour Field painting and documenting the links – and friendships – between artists such as Noland, Louis and Frankenthaler.

Links also abound between the European artists (Appel and Dubuffet for example), while Appel and Scott – who both exhibited at the influential Martha Jackson Gallery – show the fruitful connections between the New York School and painting in Europe.

Taken as a whole – and adding in some works by British artists with obvious links to international movements, such as Bridget Riley or Peter Lanyon – the collection formed by the Ulster Museum admirably fulfils Crookshank's goal of telling the story of the new art of the 1950s and 1960s.

After she announced her decision to move to Dublin, the Belfast Telegraph mourned the prospect, noting, on 4th December 1965, that 'losing Anne Crookshank as Keeper of Art at the Ulster Museum is certainly the most stunning blow the arts in Ulster have suffered recently... The trustees of the Ulster Museum must be sorely regretting that they have lost the most brilliant and acute authority on art and the most enterprising and judicious collector of new work we have in Ulster, if not in the whole of Ireland'.

If Crookshank's acquisitions were ahead of their time in Ulster, she was also in advance of taste across the rest of Ireland as well. Belfast should be grateful to Anne Crookshank for the rich, permanent legacy that her relatively short time in position at the Ulster Museum has left to the city of her birth.

William Laffan, art historian, curator and author

This article was supported by Arts Council Northern Ireland