As the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War falls this year, it is a good time to take a look at art which has both reflected and been inspired by the struggles of the First and Second World Wars.

Wartime art has always been well represented in our public collections, with the work of artists like Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) and Paul Nash (1889–1946) being immortalised for their treatment of subjects both away at war and on the home front. Despite these brilliant works being widely available to the public, some lesser-known wartime works by female artists remain under a relative veil of obscurity. Here, we would like to share some paintings by women whose art was equally compelled by the fear, grief and sometimes the mundanity of wartime Britain.

The Deluge by Winifred Knights (1899–1947) was the winning submission for the Prix de Rome Scholarship in Decorative Painting. Knights' artwork exemplified a revival of religious imagery that characterised the painting of many British artists in the 1920s, particularly Stanley Spencer.

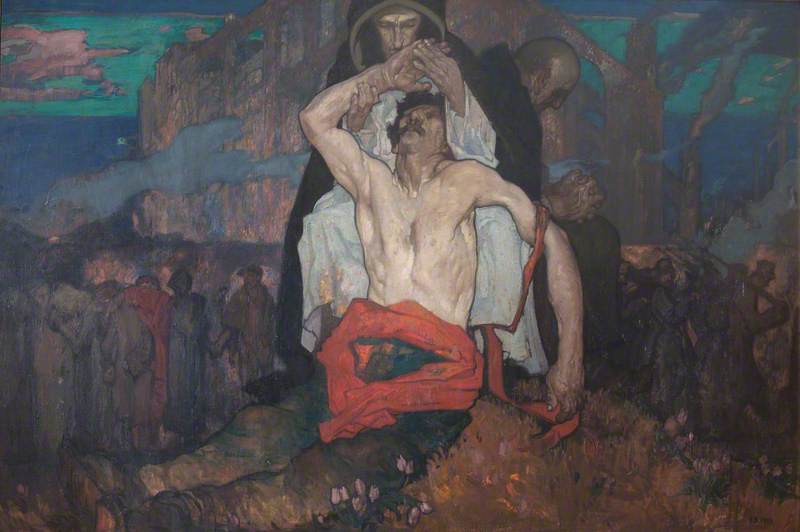

Completed in the wake of the First World War, Knights' painting depicts a biblical flood that engulfs her friends and family, driving them into a state of frenzy. As the dam is breached, her loved ones become swept up in the flood. Two figures can be seen in the distance clutching onto land. The artwork is an allegory of Knights' experience of war and may also have reflected the trauma she experienced in witnessing the detonation of a TNT plant at Silvertown, East Ham on 19th January 1917. It was the largest explosion on British soil during the First World War, with 600 homes flattened and the loss of 73 lives.

Knights is represented in the middle of the painting, seemingly at pains to navigate the chaos around her. A clergyman is shown to the artist's left, escaping up the hill. This may reflect the ambivalent attitude that Knights felt the Church had adopted during wartime.

A Child Bomb Victim Receiving Penicillin Treatment

1944

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

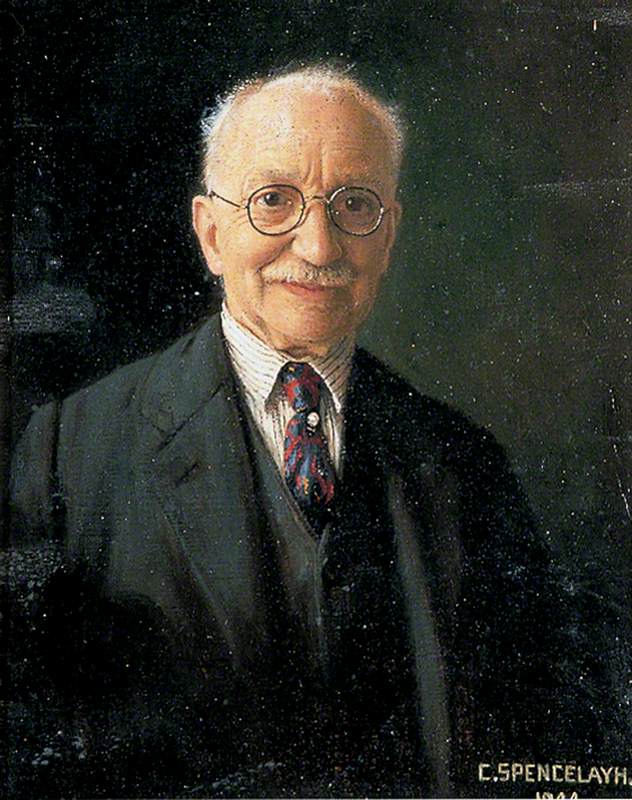

Born in France, Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950) moved to England to study at the age of 14. Her time studying art was then split between Paris and London where she notably learned lithography under F. E. Jackson at The Central School of Arts and Crafts. Gabian spent many years in England printmaking and painting before moving to Italy due to ill health. On her return to London in 1927, Gabian began to make more works in oil in response to a shortfall in her print sales. By 1940, her career had flourished and she was elected President of the Society of Women Artists.

A Child Bomb Victim Receiving Penicillin Treatment was suggested by Gabain as a commission to the War Artists Advisory Committee after discussions with Alexander Fleming, the inventor of penicillin. In her letter to the committee, Gabain stated that penicillin had 'saved numberless lives on all the battle fronts, and everyday it is becoming more potent as a saver of life – it seems a thing so worthy of record in all the destruction of war.'

Despite Gabain's initial assumption that the child depicted was a bomb victim, it was later revealed that she was in hospital because of a road accident. Nevertheless, the painting conveys a feeling of security and stability afforded by the penicillin treatment. Gabian uses a triangular structure to reinforce this stability. The structure that holds the child's leg, as well as her posture in the bed, trace a trilateral format that has been used for centuries in art history to provide an image of stable grounding.

A Women's Royal Naval Service Officer

c.1940

Elsie Gledstanes (1891–1982)

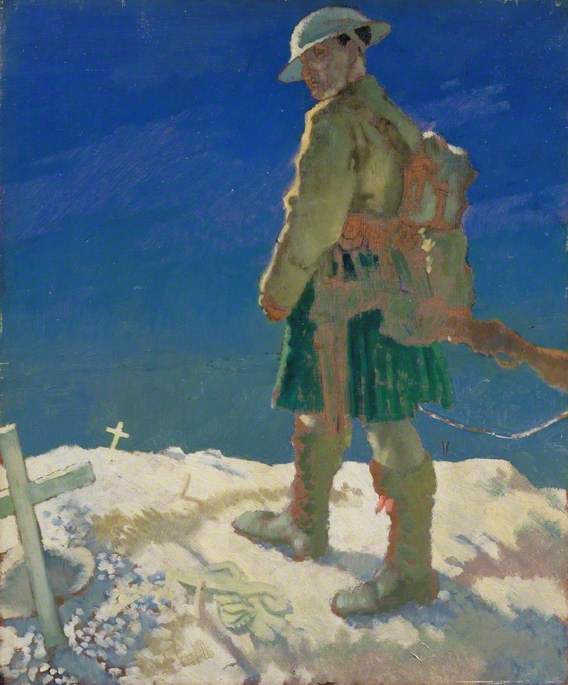

Elsie Gledstanes (1891–1982) was another woman artist who trained in both Paris and London. A regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy, Gledstanes worked as an auxiliary ambulance driver in London and a driver for the Women's Legion in the Second World War. This may be how she came into contact with her subject for this painting. This officer sits proudly on her desk, coat laid over the chair. Behind her is an illustration of different aircraft types, as well as a Morse key and what appears to be a lamp or box on the desk.

Upright, with a glove set down on her lap, the sitter is convincingly portrayed by Gledstanes as an elegant woman with the assertiveness and power of an officer.

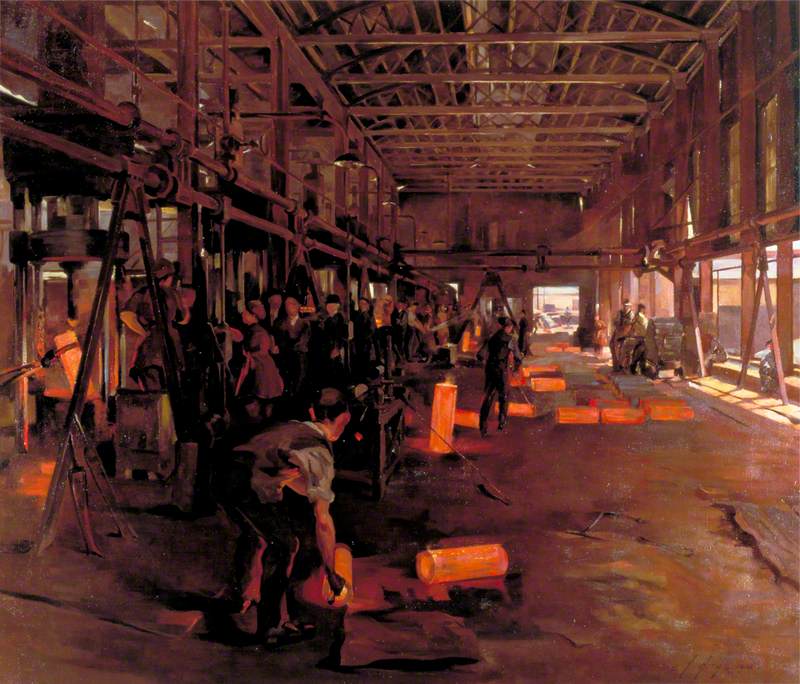

Laura Knight (1877–1970) was one of a handful of women artists to be officially commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee. In becoming a member of the Royal Academy in 1936, the first female member in 168 years, she was an outstanding and unprecedented exception to the history of male academicians.

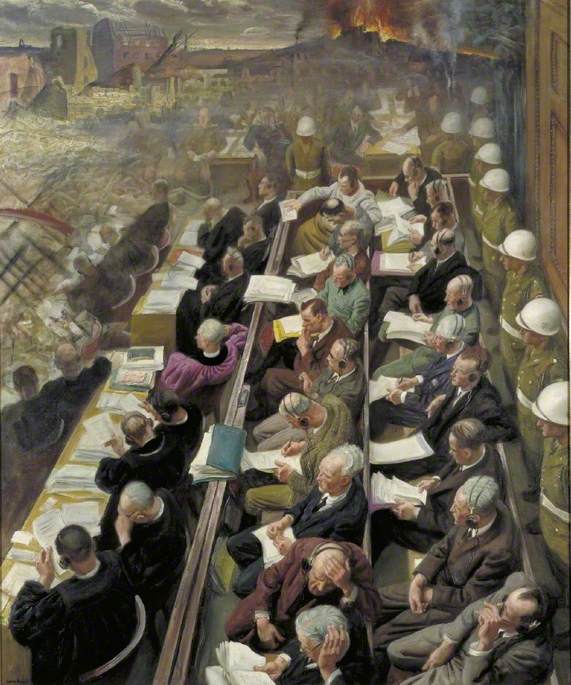

In for Repairs portrays a team of women fixing a barrage balloon as part of the war effort. These devices were used to defend cities from enemy planes. Knight blends an impressionistic painterly treatment of the vast fabric with a rendering of the women in functional masculine clothing. This scene is one of the more tranquil depictions of war that Knight painted; her work saw her also produce paintings of the Nuremberg trials in 1945–1946.

The Burning Down of Huts in Camp 1, Belsen Concentration Camp

1945

Doris Clare Zinkeisen (1898–1991)

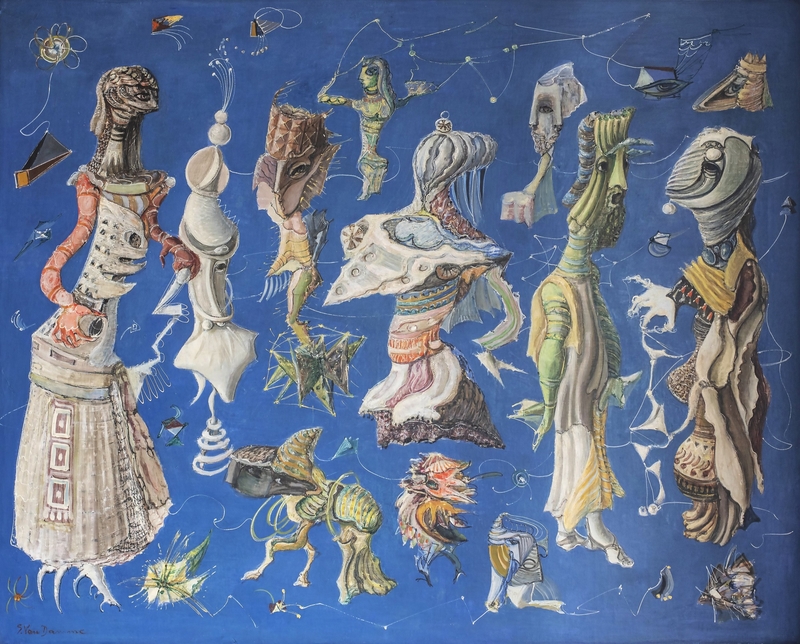

A war artist's greatest and most difficult task is to somehow communicate the horrors of war. This painting was made by Doris Zinkeisen (1898–1991) after she visited Belsen concentration camp shortly after its liberation in 1945. Its restless, hasty brushwork gives some indication of what people who discovered the camps might have been feeling. The forms deconstruct as they approach the focal point of the image and oppressive grey clouds loom thickly overhead.

Zinkeisen volunteered her services as an artist to the North-West Europe Commission, working with the British Red Cross as they moved through a decimated Europe. Zinkeisen was a well-regarded artist. She trained at the Royal Academy and went on to exhibit work in London, Paris and the United States. Before making artworks during the war she worked as a nurse in London helping Blitz victims.

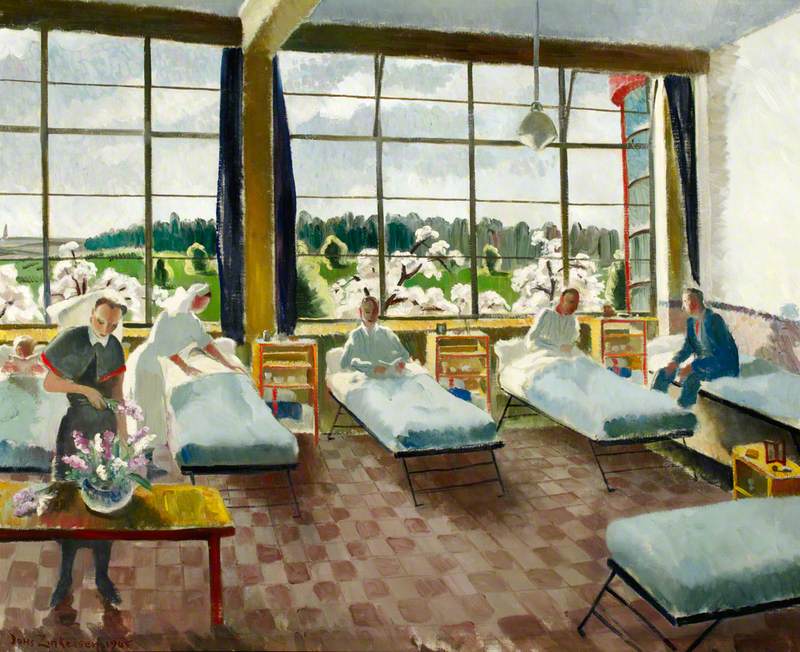

C Ward, 101 British General Hospital, Louvain

1945

Doris Clare Zinkeisen (1898–1991)

Each of these artists shows us a unique perspective on the varied experiences of wartime, both in Britain and Europe. They champion both the female artist and female subject as integral parts of the war effort beyond the home front. Collections, curators and historians are increasingly seeking to address the imbalance of female representation in art history and these women demonstrate a shining example of the compelling contributions made to wartime art.

Jack Lazenby, freelancer writer