The world that emerged in the decade following the First World War – wrecked and traumatised on one hand, hungry for pleasure and freedom on the other – was one in which women, and women artists, engaged in complex ways.

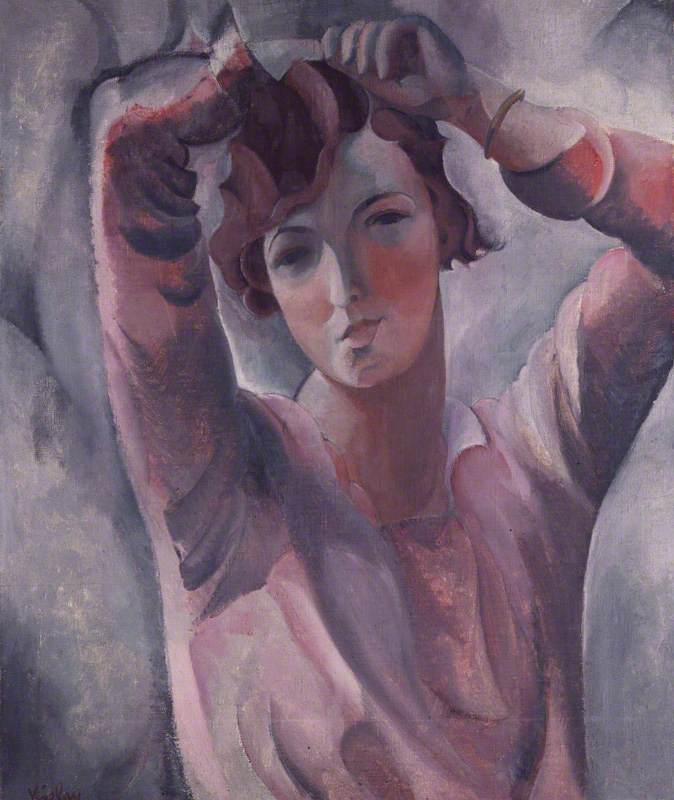

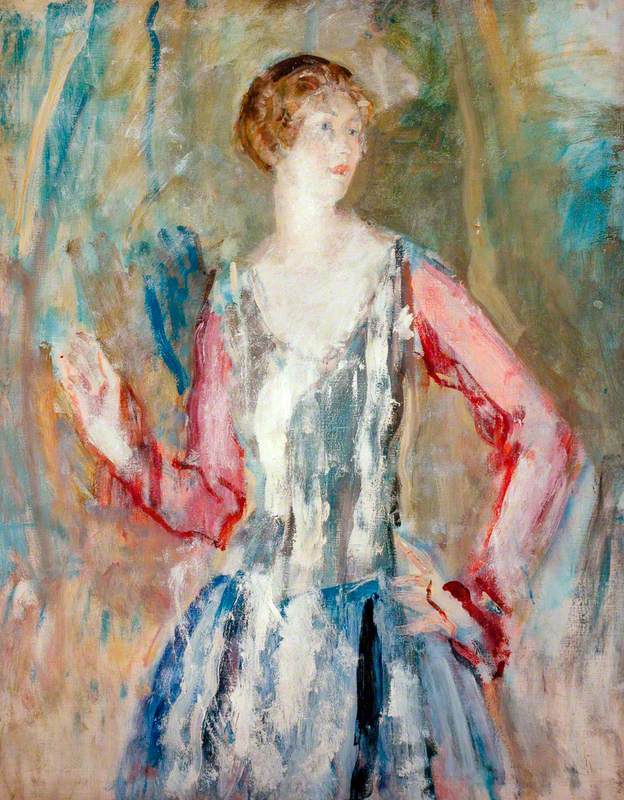

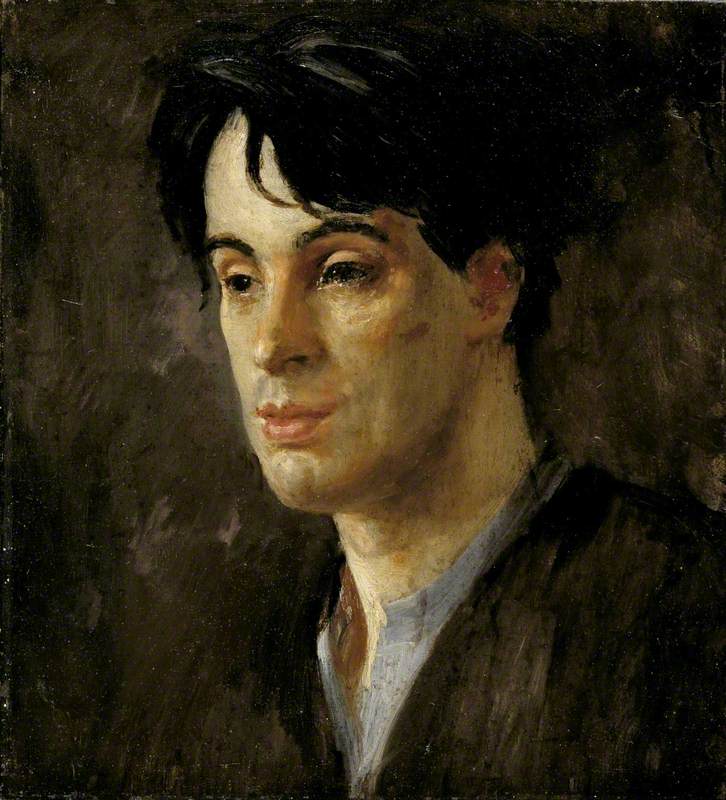

Portraits such as the one below of the heiress Nancy Cunard, with her chic short hair and evening gown, seem to epitomise the 'Bright Young Things' of the 1920s: hedonistic youth intent on forgetting the old order that had ended in such bloodshed. But the sitter in Ambrose McEvoy's portrait was a more interesting woman than this portrait suggests. A poet and publisher, Cunard was also a committed anti-racist and anti-fascist activist, her radicalism far more than just a pose.

As the backdrop to Cunard's youth, the 1920s are often simplistically described as the 'roaring twenties'. But this decade was a more complicated time, a period of fraught division and increasing financial instability, leading to the General Strike in the UK in 1926, and the Wall Street Crash in the US in 1929.

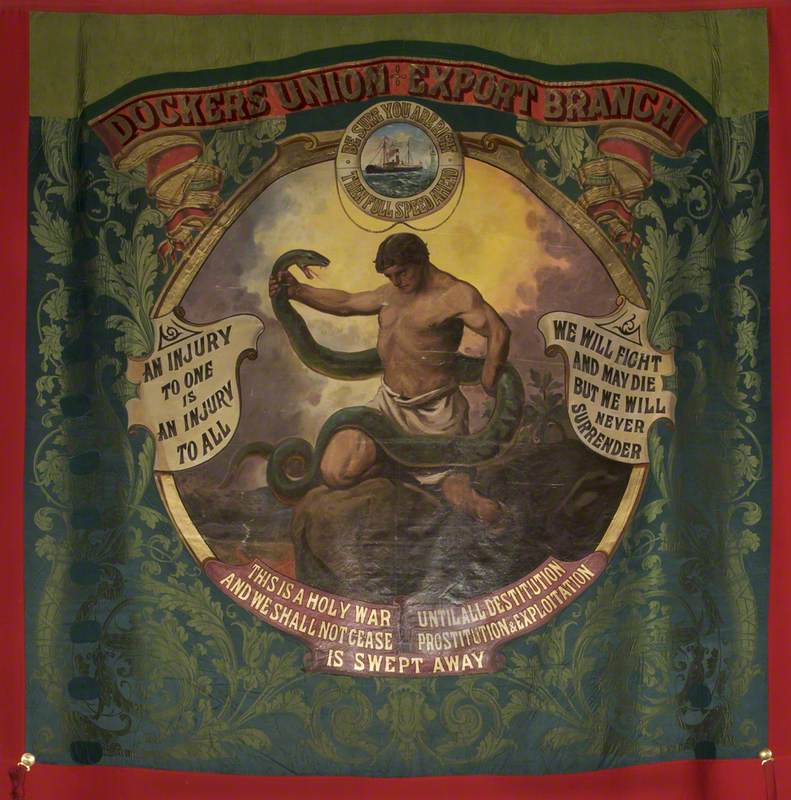

The General Strike

1926, photograph by unknown artist

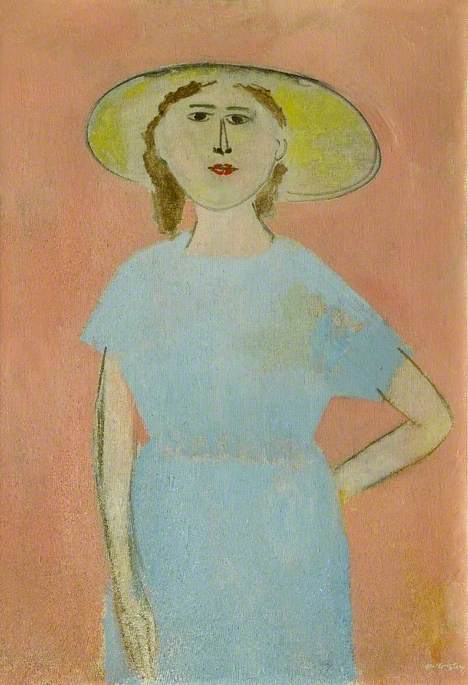

For women artists, many of whose careers had come to a halt during the conflict, a renewed commitment to their work played out against this divided world, in which progress clashed with reactionary retrenchment. By the end of the decade, the rise of fascism in Europe encouraged and expected the return of women to the domestic sphere.

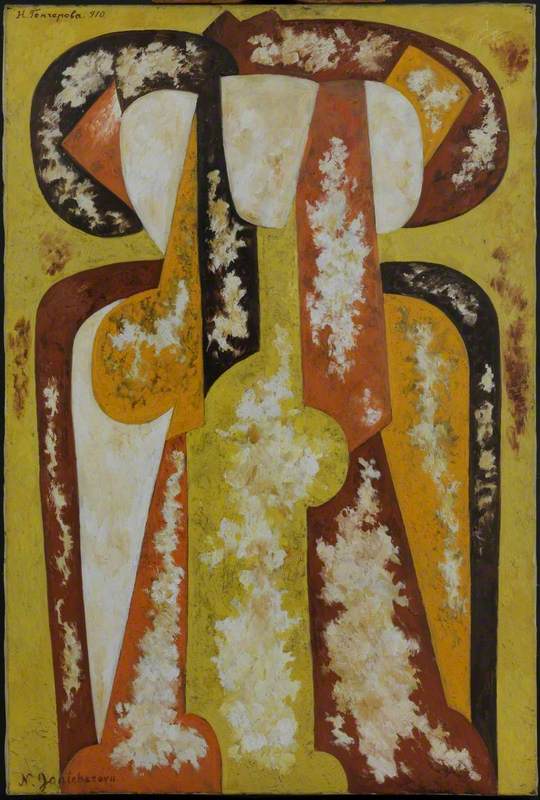

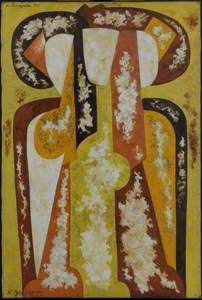

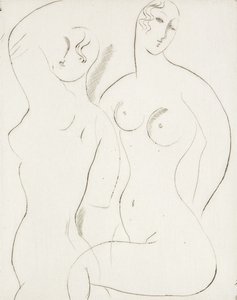

Yet at the start of the 1920s, international travel had opened up, meaning that artists from across the world flocked to Paris. The Russian-born artist, Natalia Goncharova's Three Young Women, with its bold reduction of form and re-interpretation of the classical subject matter of the Three Graces as abstracted youth, evokes the spirit of a new age.

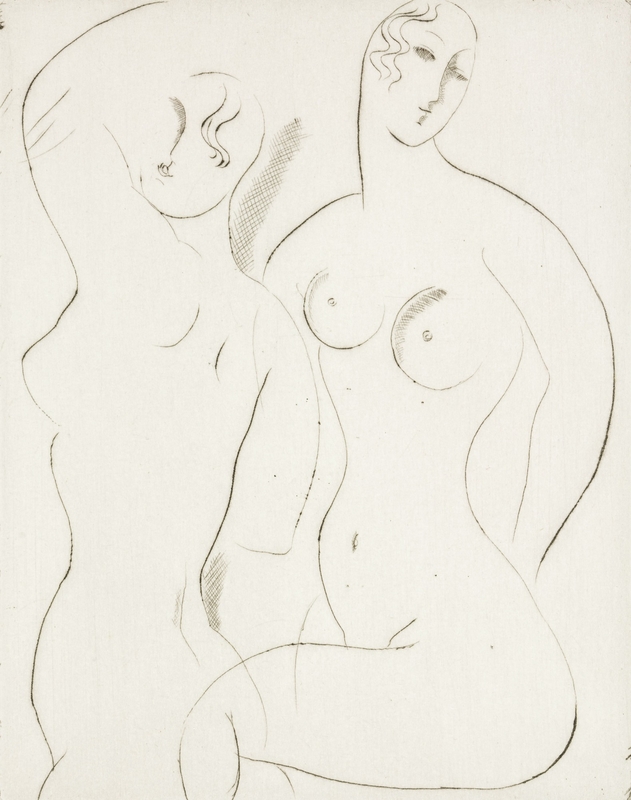

Other women artists who gravitated towards Paris included the Irish painter Mainie Jellett and Polish-born painter Tamara de Lempicka, both of whom became heavily influenced by Cubism in the early 1920s, while artists such as Marie Laurencin and Sonia Delaunay also became central figures of the Parisian avant-garde.

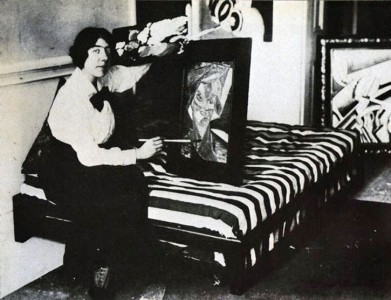

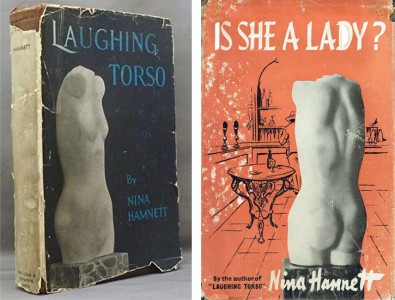

The Welsh artist Nina Hamnett, who had spent the war years unhappily marooned in London, also returned to the French capital to live. She painted a fellow refugee from the UK – the ballet dancer Rupert Doone – and made a series of watercolours of Parisian café life, which she sold in London in the 1920s, serving the appetite for travel to France.

Within the art world, there was some (if rather slow) increase in the presence of women. For the first time, at the Venice Biennale in 1924, women were involved in selecting works for the British Pavilion. Lady Cunard, the patron, society figure, and mother of Nancy, served on the committee that year, alongside the painter Laura Knight.

In Weimar Germany, women artists were permitted to join the Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919. Artists and designers, such as Anni Albers and Margarete Marks (née Heymann) specialised and excelled in mediums such as textiles, design and photography.

In Britain, the London Group – in which women had not been well-represented – took an ex-suffragette, Diana Brinton, as its secretary during the 1920s and she worked hard to increase the representation of women at its shows. Thus, artists affiliated with such circles, Jessica Dismorr and Paule Vézelay, exhibited regularly during the 1920s.

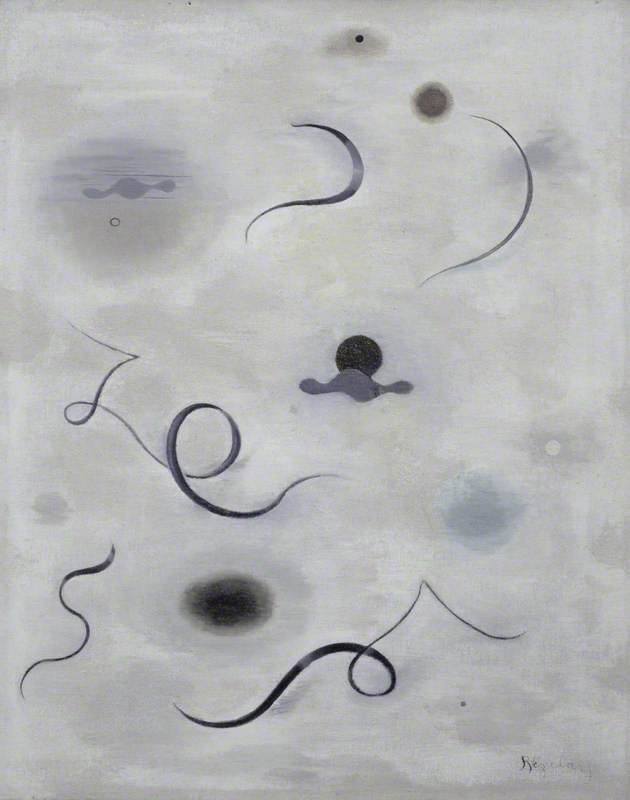

Vézelay, whose birth name was the quintessentially English 'Marjorie Watson Williams', left her home city of Bristol and settled in France. Her new identity (adopted in 1926) signalled a profound break away from her roots and alliance with France and its art. Within only a few years she had become a pioneer of abstraction.

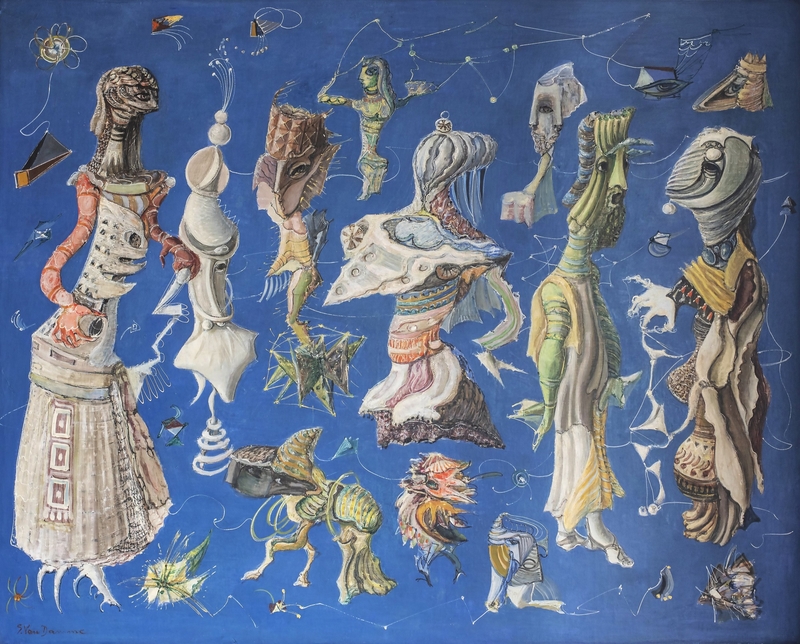

It was in France, too, that one of the most influential movements of modern art was formed in the 1920s: Surrealism. The poet André Breton instigated this new avant-garde movement, publishing the first Surrealist Manifesto in Paris in 1924. Surrealism, which he described as, 'pure psychic automatism' was intended as a revolutionary movement across art forms, a critical response, in part, to the fantasy of man's rationality which had plunged the world into war.

The Surrealists took as their touchstone Sigmund Freud's new theory of psychoanalysis, the belief that irrational and unconscious fears and desires govern human beings, and that the work of the artist was to release and represent them.

For women artists, Surrealism was a paradox. On the one hand, the idea of art as a critique of society and designed to overthrow conventions seemed to offer an escape from hidebound ideas of femininity. Yet, on the other hand, it emphasised the notion that women serve as beautiful objects of desire, as muses for the art of their male Surrealist colleagues. Despite this balancing act, women inspired by the movement, such as Claude Cahun, Dora Maar, Lee Miller and later many others such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and Meret Oppenheim made astonishing work.

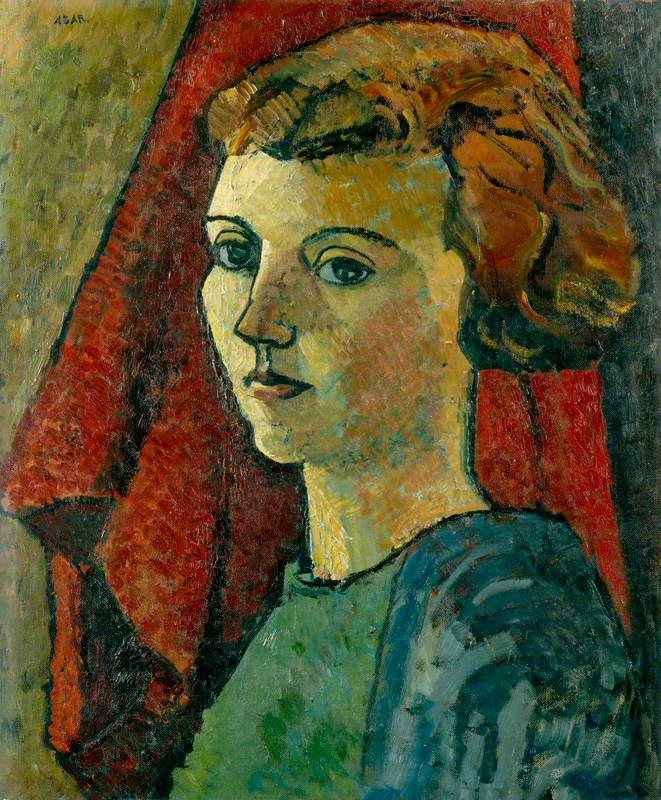

The Buenos Aries-born artist Eileen Agar's strong yet conventionally realist painting of 1927 would evolve into pioneering work, including abstract paintings and sculptures made of found objects in the 1930s. While the now lesser-known Birmingham artist, Emmy Bridgwater, also worked across disciplines and media, making collages, paintings, drawings and poems out of her dark fantasies.

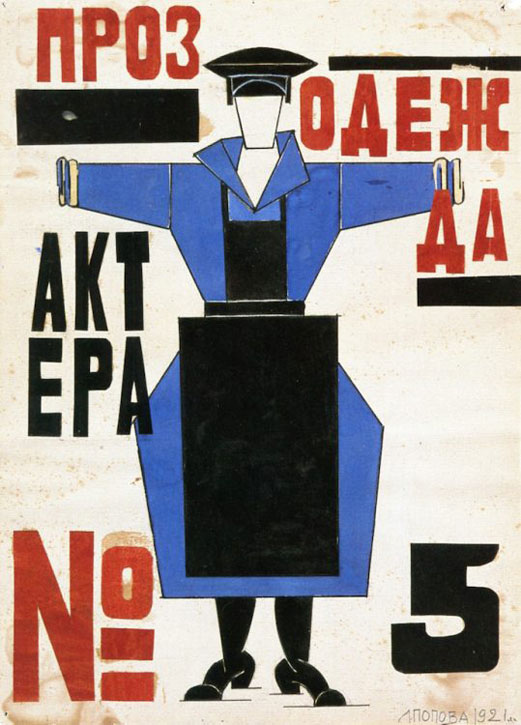

As politics polarised over the decade, art was shaped by new extremes. Revolution in Russia had seemed at first to herald an outpouring of radical inventiveness and experiment, epitomised in the work of the Constructivists, among them women such as Varvara Stepanova and Lyubov Popova.

Working Clothes for Actor No.5

1921, pencil & coloured wax on paper by Lyubov Popova (1889–1924)

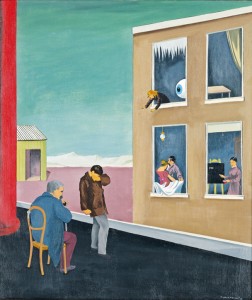

But as the regimes of Communism and fascism established themselves, artistic independence and innovation were viewed with suspicion, and then repressed outright, in favour of safe realism on both left and the right. In Russia, the artist Maria Bri-Bein, who had begun her career as a modernist, reverted to a kind of academic figuration to serve the regime as the 1930s began.

Telegraph/Radio Operators (1933) by Soviet poster artist Maria Bri-Bein #womensart pic.twitter.com/h2V1ZlV99g

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) May 11, 2019

We should end, though, on two moments of hope and breakthrough. In 1928 women in Britain were granted voting rights on the same terms as men: aged 21 rather than 30, and with no requirement to be a householder.

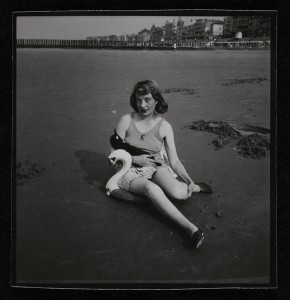

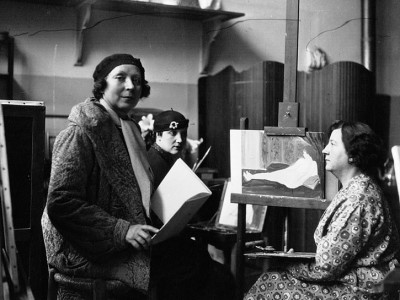

In the US, the Black artist, designer and teacher, Loïs Mailou Jones set out on her long and distinguished career. In 1922, at the age of 17, she had her first solo exhibition at Martha's Vineyard and spent the following few years training at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She would make her name in Paris over the following two decades, though Jones was greatly influenced by the cultural movement in New York known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Loïs Mailou Jones

1937–1938, photograph by unknown artist

Progress, though never a straight unchallenged line of continuing enlightenment, nevertheless is difficult to defeat entirely and forever once substantial gains have been made. These moments of advance for women meant that resistance was to come in the 1930s, as fascism rose to prominence. Although devastating, the extreme political climate could not completely thwart the rise of women artists and their increasing presence and visibility.

Alicia Foster, curator