The first half of the nineteenth century saw a transformation of Welsh society. Industrialisation in the coal-mining districts of the south and north-east, and the development of the slate quarrying districts of the north-west are familiar features of that transformation, and have been closely studied.

Less familiar, although related to the general increase in economic activity represented by these developments, was the rise of the middle class, and the rapid expansion of small towns all over the country. For the first time in Wales a substantial class of professional people with disposable income, alongside successful traders and craftspeople, provided patronage for the arts on a large scale. In the visual arts, that patronage was directed mainly towards portrait painting, and William Roos (1808–1878) was perhaps the most characteristic of a group of painters who were the beneficiaries.

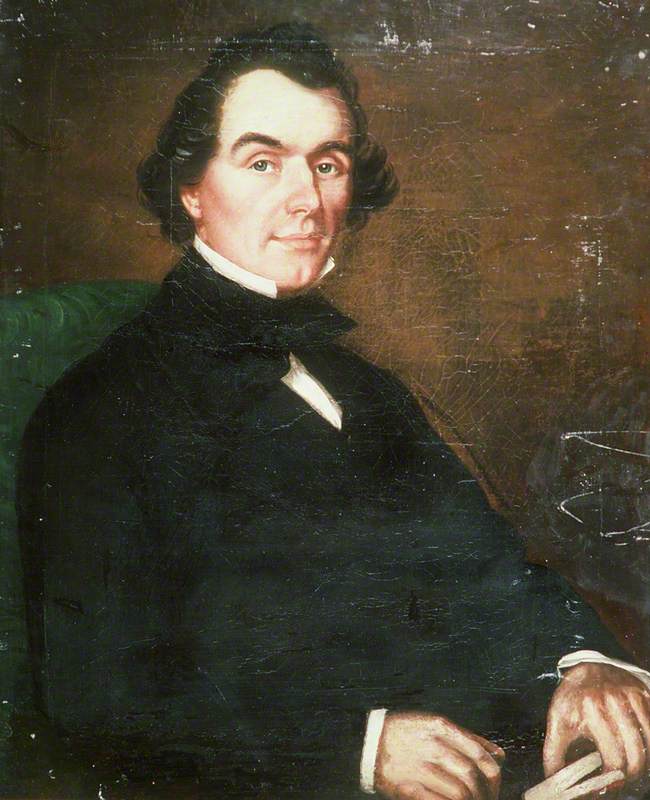

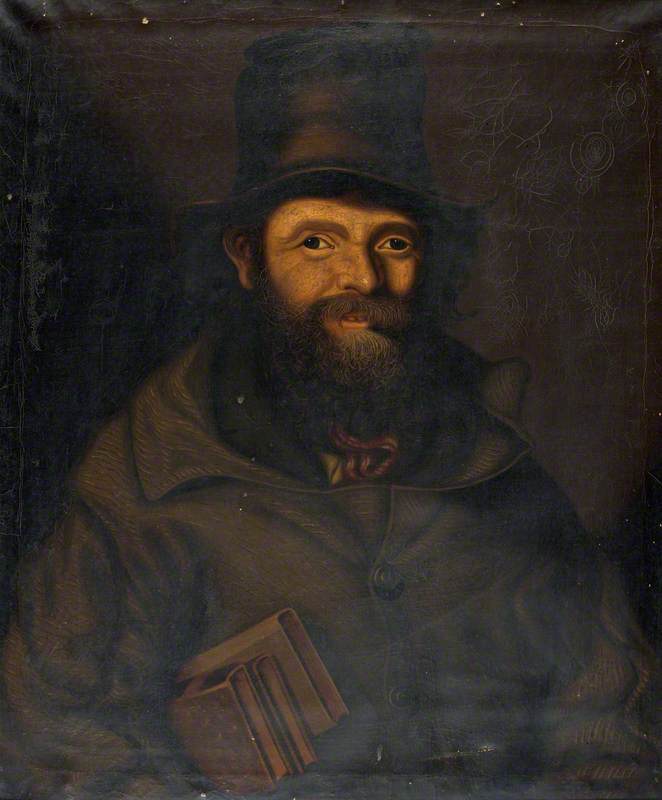

Thomas Charles of Bala (1755–1814)

c.1840

William Roos (1808–1878)

The evolution of artistic practice in Wales in the period followed a different course to that in England. In the absence of political self-determination, the increasing prosperity of the Welsh nation did not result in the development of a metropolis. Patronage in the first half of the nineteenth century remained dispersed widely over the country and among expatriate communities of Welsh people. As a consequence, the leading portrait-painting practitioners, including Roos, were, of necessity, itinerant.

A few regional centres within the country, notably Caernarfon, might sustain a practice for an extended period, as also the expatriate communities in London and Liverpool, but in the main, specialist portrait practitioners remained only for short periods in one place, exhausted the patronage available, and then moved on. The most productive itinerants, Roos himself and Hugh Hughes (1790–1863), were truly national figures, working throughout the country and among the diaspora, and depending almost exclusively (even when in London and Liverpool) on Welsh patrons.

Again, in the absence of a metropolitan hub, no centralised system of art education emerged in Wales itself. Few of those aspiring artists who left Wales to train academically in London or in Rome would return. The itinerant painters who sustained practice in Wales itself were either self-taught or trained in a craft tradition. Hughes, the main competitor to Roos in the portrait market, had trained as a wood engraver. Roos himself seems to have been self-taught.

A further feature of the evolution of Welsh society in this period uniquely marked the nation's painting practice. In the absence of a metropolis, intellectual leadership, emerging mainly from the professionalised religious denominations and from the arts themselves (and in particular literature), was also dispersed throughout the country and the diaspora. Nevertheless, discourse was intense, facilitated through a flourishing printing and publishing industry, and conducted primarily through the Welsh language. The faces of this dispersed aristocracy of public intellectuals were recorded by the same itinerant artisan painters as the broader middle class. They were not, as in more centralised European countries such as England, recorded by a sedentary elite of academically trained artists.

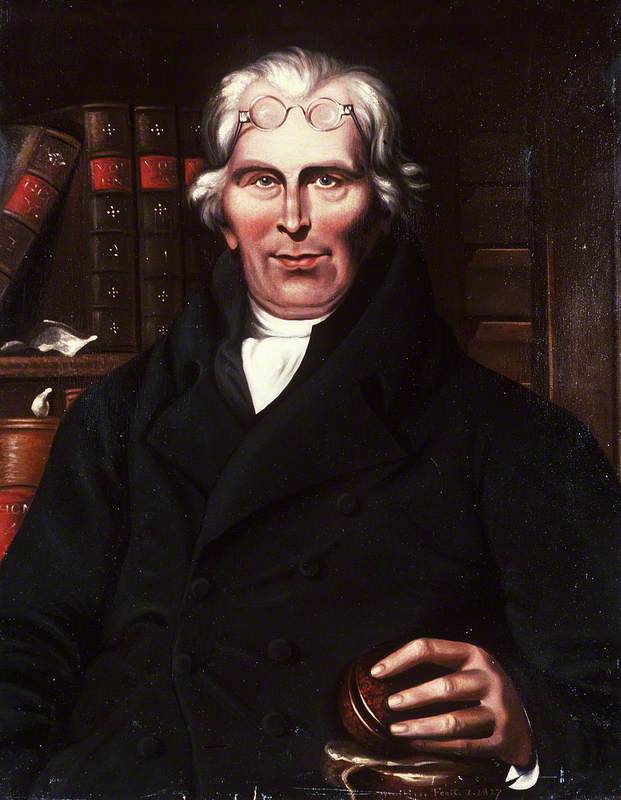

William Roos was born in 1808 on a smallholding called Bodgadfa, at Amlwch, in Anglesey. The town was the centre for the export of copper from the flourishing Parys Mountain mines. His grandfather, who was of Dutch extraction, had been closely involved both with the mines themselves and with shipping. Roos received some education at a Navigation School in Amlwch, and although there is no reason to suppose that he was taught drawing there, at the age of 19 he was able to develop from an engraving a competent portrait of a celebrated schoolteacher, John Williams of Ystrad Meurig (National Library of Wales).

Reverend John Williams 'Yr Hen Syr' (1745–1818)

1827

William Roos (1808–1878)

Six years later, in 1833, Roos married Ellen Jones of Trewalchmai in Anglesey, and the following year he advertised his presence in Caernarfon, offering to paint miniatures at a guinea, 'Half Size Portraits' at two guineas, and 'Three Quarters Lengths' at four guineas.

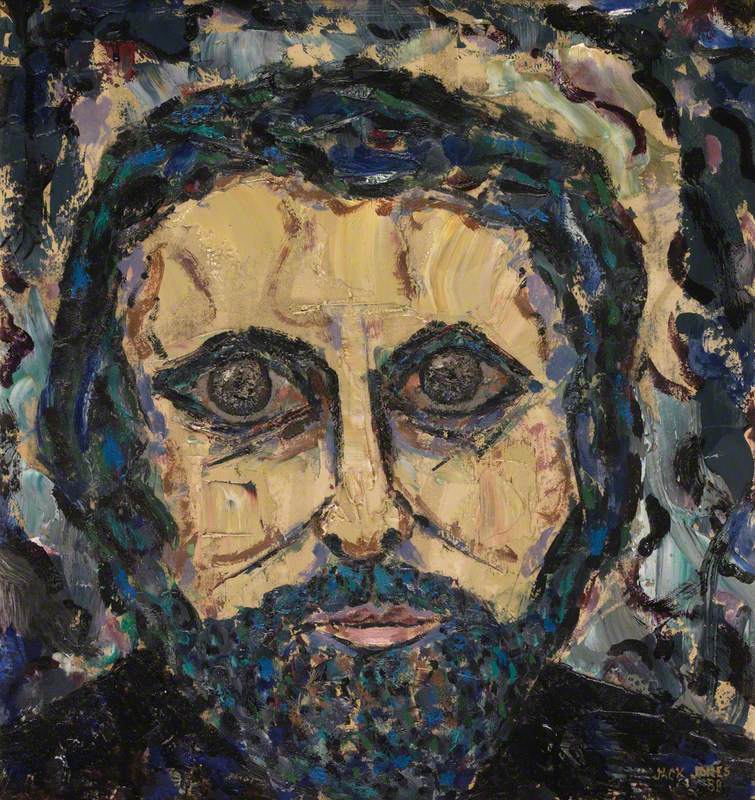

Taking advantage of the fact that he lodged next door to him, in 1835 Roos painted a small portrait of Revd. Christmas Evans, the most celebrated Baptist minister and preacher of the period in Wales.

Christmas Evans (1766–1838)

1835

William Roos (1808–1878)

Although in style the picture would prove to be untypical of his overall output, this portrait, disseminated in the form of a mezzotint engraved by Roos himself would help to fix the striking image of the man in the public imagination. He produced for sale at least two subsequent copy versions in oil (National Museum of Wales; National Library of Wales).

Reverend Christmas Evans (1766–1838)

1835

William Roos (1808–1878)

Roos would repeat this strategy of copying and of dissemination of his portraits through engravings with other public figures who sat to him, such as the poet Robert Williams, 'Robert ap Gwilym Ddu' (National Library of Wales).

Robert Williams (Robert ap Gwylim Ddu)

1851, lithograph by William Roos (1808–1878)

Four oil versions and a drawing survive of his original portrait of the celebrated Richard Robert Jones, 'Dic Aberdaron' (National Library of Wales).

Dic Aberdaron (Richard Robert Jones) (1780–1843)

c.1850

William Roos (1808–1878)

Characteristic of his work for less celebrated individuals were his portraits of the Aberystwyth printer, John Cox, and the four portraits of the Anglesey farming family of Hugh and Margaret Thomas of Hendregadog, Llangaffo, in Anglesey (National Library of Wales).

Margaret Mary Thomas (d.1872)

1847

William Roos (1808–1878)

The decade of the 1840s was the high point of Roos's career, but in fact, by 1847, when he painted the Thomas family portraits, the negative impact of photography on the market for oil-painted portraits was beginning to be felt.

William Thomas (1825–1862)

1847

William Roos (1808–1878)

The response of Roos and other artisans was to diversify their practice. Because of long exposure times, portraits of prize farm animals and equestrian portraits for the hunting fraternity remained the prerogative of painters. Among his finest equestrian works was a portrait of Robert Luther of Acton, Shropshire, taken in 1849 (Ludlow Library & Museum Resource Centre).

It was primarily in the border counties that Welsh artisans found the small amount of English patronage that they attracted.

In 1846 Roos had married for a second time. His wife, Mary Jones, was from Merionethshire, and the couple settled in Tywyn, on the west coast. Roos's daughter by his first wife died the following year, but Mary bore him four further children. Despite his limited formal education, Roos was familiar with European art history as understood in the period, and with aspects of Welsh art tradition.

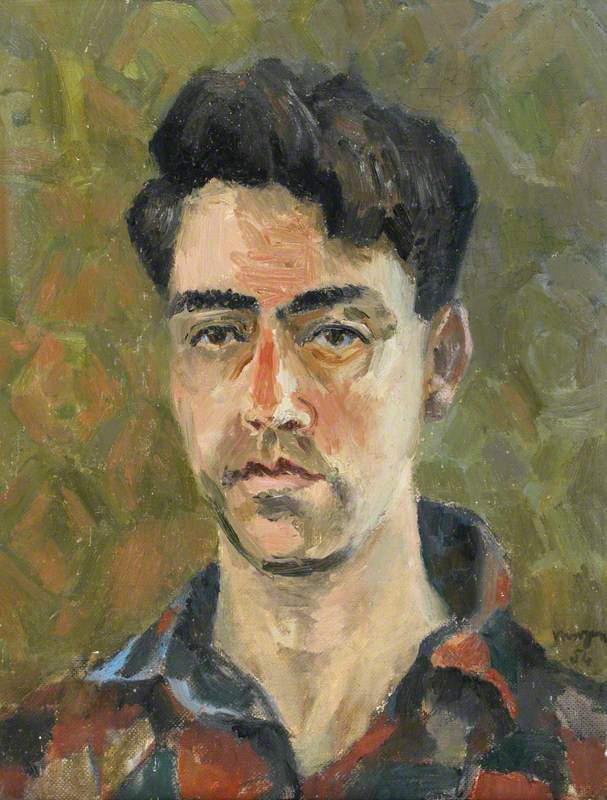

Hugh Derfel Hughes (1816–1890)

1844

William Roos (1808–1878)

In 1844 he had written a letter to a fellow itinerant, the poet Hugh Derfel Hughes (National Library of Wales), outlining the tradition from the Egyptians to the present, and drawing particular attention to the Roos family of painters who had flourished in the Low Countries from the seventeenth century.

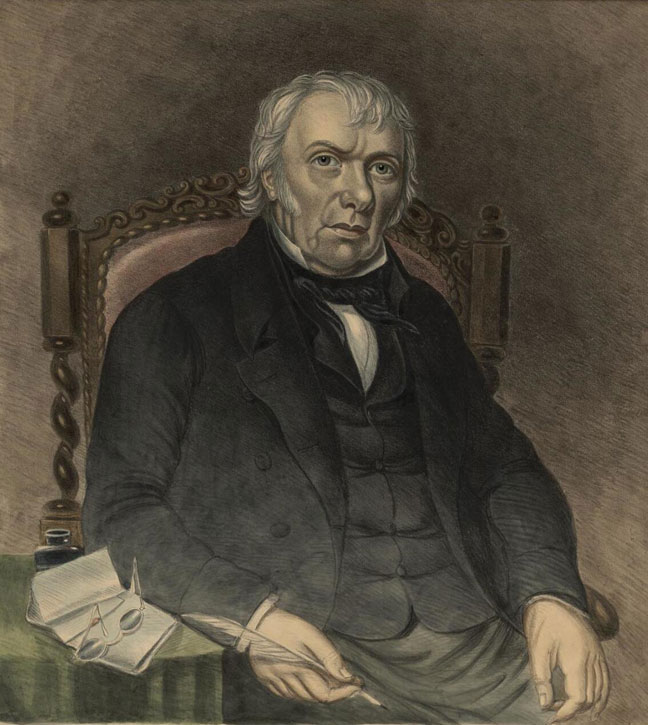

John Jones, Talhaiarn (1810–1869)

1864

William Roos (1808–1878)

Among Roos's informants was a leading Welsh intellectual of the period, the poet John Jones, Talhaiarn, who worked in London as an engineer. Roos painted Talhaiarn as The Bard in Meditation (National Museum of Wales), drawing on a long tradition of Welsh bardic iconography. In 1851 he painted the same sitter, who at the time was working as assistant to Paxton on the construction of the Crystal Palace, in sober dignity as the successful Welshman in London (National Library of Wales).

John Jones (Talhaiarn) (1810–1869)

1851

William Roos (1808–1878)

The popularity of photography forced Roos's career into steep decline in the 1860s. In 1871 he made a brief attempt to establish himself as an engraver in London, moving his whole family to an address in Soho, but they returned to Wales and Roos himself to the itinerant life after a year or so. In 1873 he wrote to a well-placed friend asking for his recommendation to potential patrons who owned prize cattle or hunters, observing that 'I have taken to Animal & Landscape painting for the last few years, this is the only thing in art Photography can't do.'

He seems to have had little success with landscape, as only a few signed works survive. Attempts at history painting, submitted to national competitions at Eisteddfod festivals met with equally limited success. His last years were marked by some undignified appearances in the police courts, in dispute with clients over payments. The last eye-witness account reported that he was at work in Oswestry churchyard, tinting photographs of the church 'which enhanced their sale value by a few shillings.'

In the final year of his life, Roos made his way back to Anglesey, where on 4th July 1878 he died of a stroke at Amlwch, in the presence of one of his sons.

Peter Lord, art historian

The free exhibition 'William Roos: Portrait of an Artist', curated by Peter Lord, is on display at Oriel Môn in Anglesey from 1st February to 5th July 2020

Further reading

Peter Lord, William Roos and the Itinerant Life, Oriel Môn, 2020

Peter Lord, The Tradition: a New History of Welsh Art, Parthian, 2016, pp. 163–167; 194–195

Peter Lord, The Visual Culture of Wales: Imaging the Nation, University of Wales, 2000, pp. 186–200; 214–219; 236–239