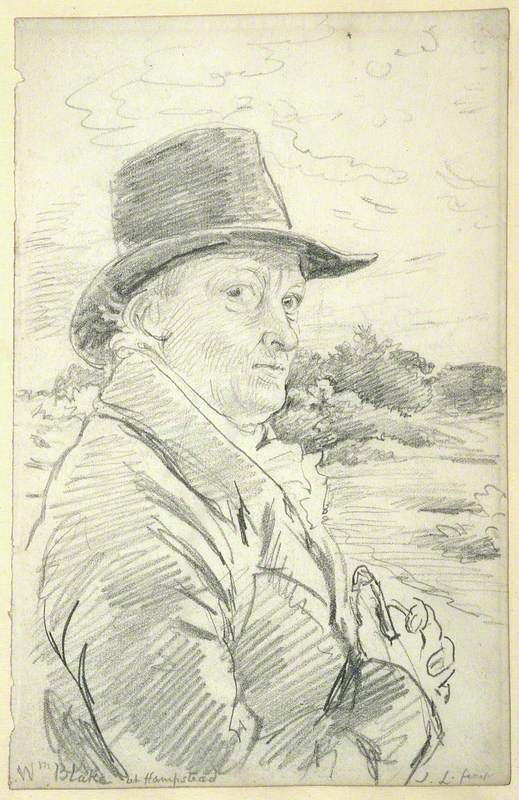

Although William Blake was barely recognised for his creative skills during his lifetime, today, he is revered for both his artistic talent and profound poetry.

Born on 28th November 1757 in Soho, London, Blake is remembered as an influential and pivotal figure of the Romantic Age. Both his poetry and art are filled with symbolism and allegory, utilised and demonstrated through his own interests and points of study – the classical figure, mythology and religion. Each of these features recur continuously throughout Blake's artistic practice and were used as tools to expose and criticise society and the world surrounding him.

Blake began to write and paint during his early years, skills which his family encouraged. Experimenting with various mediums such as engraving, prints, illustrations and paints, his open and adventurous attitude toward both his content and tools demonstrated his exciting and unique approach to the arts.

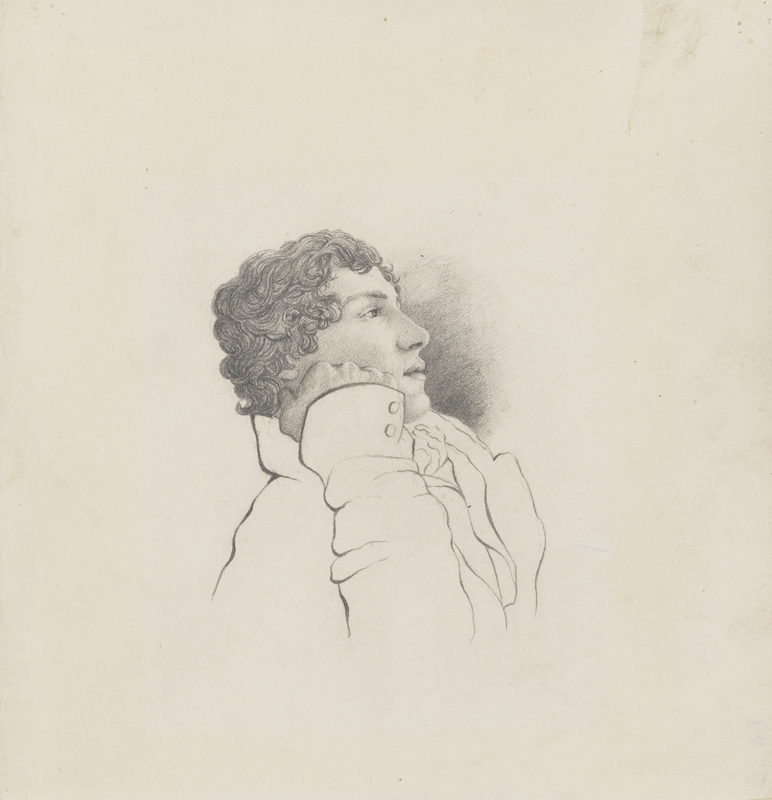

At 21, Blake completed a seven-year apprenticeship at Basire, becoming a journeyman copy engraver – allowing him to work for various London book and print publishers. Later, in 1779, he was accepted into the Royal Academy of Arts' School of Design, in order to further his prospects as a painter. It was here that Blake immersed himself in the work of artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo, making use of the school's antique sculptures and refining his interpretation of figures and the body.

Blake's involvement in both the literary and art world is shown throughout his creative practice. Blake depicted various poets and writers of influence, such as William Shakespeare, Geoffrey Chaucer and Alexander Pope.

Scenes influenced by such writers are also seen throughout his oeuvre and further highlight his dual interest in both the visual arts and literature. During the late 1780s and 1790s, Blake began to work on illuminated books.

Perhaps one of his most revered and recognised productions was Songs of Innocence, a compilation of short lyric poems alongside his own illustrations and drawings. These drew on familiar children's stories but provided a much darker and scathing critique on the society at the time. This use of innocent childlike prose – which, in truth, disguised a much more sinister message – is a method that is still utilised today.

William Blake was born #onthisday in 1757. Here are the title pages for Songs of Innocence and of Experience pic.twitter.com/LWnLxTwAzF

— British Museum (@britishmuseum) November 28, 2013

Later, in 1794, Blake also produced a parallel illuminated book of poems titled, Songs of Experience. The two collections were intended as a depiction of the two contrasting states of the human soul, and included Blake's famous poem The Tyger.

The year of 1809 saw Blake curate his first and only solo exhibition at his brother's shop on Broad Street. Blake's continued disappointment with the art world was highlighted within the exhibition's manifesto or Descriptive Catalogue. Here, he discussed the issues with aesthetics and the art world of the time and through his exhibition attempted to showcase the style and creative ethos that he wished to push forward.

Blake also explained and defended his depiction of Chaucer's characters and discussed his views and opposition to Venetian and Flemish painting.

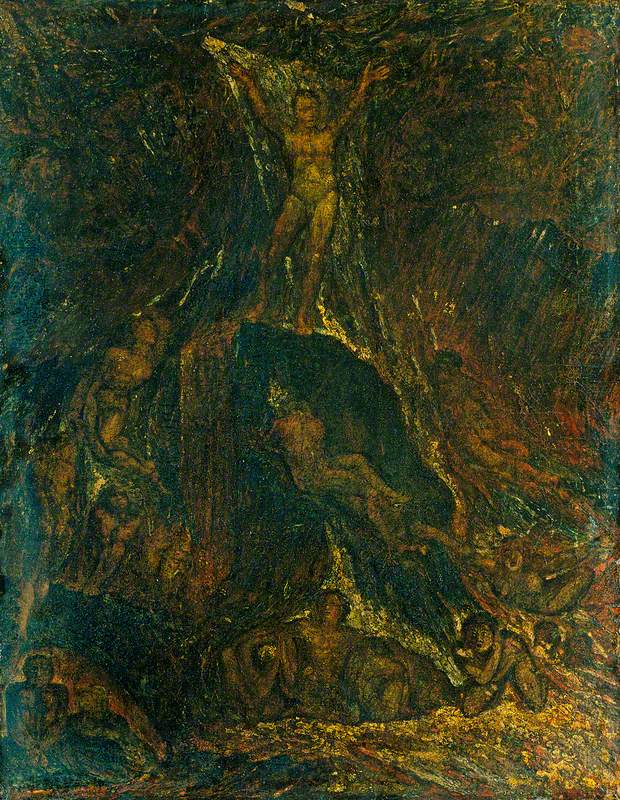

The exhibition itself presented Blake's depictions of Chaucer's The Canterbury Pilgrims and another 15 experimental paintings, including The Bard, from Gray and Satan Calling Up His Legions. Unfortunately, Blake's exhibition was not a success and this marked a period of time which was particularly slow within Blake's career.

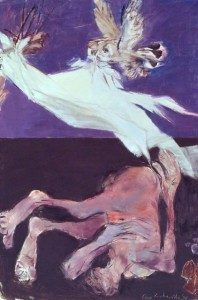

The works featured at the exhibition were predominantly experimental and varied in technique. Satan Calling Upon His Legions, is a gloomy and moody image.

Composed of blacks, blues, and greens – the landscape surrounding the figures seems two-dimensional and non-descript. Out of the darkness you can just make out the shape of a mountain, and slight depth. On further examination, figures can be seen strewn across a rock, while Satan stands with arms spread at the pinnacle. Here, Blake was attempting a new technique of applying paint without any 'oily vehicle', hence its final, darker, outcome. This was not an uncommon side effect.

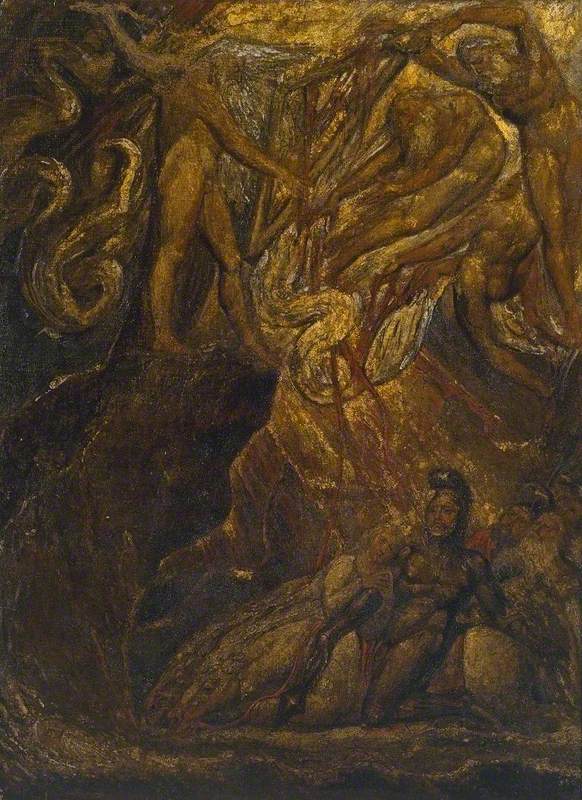

Other works such as The Bard, from Gray, has also suffered discolouration due to Blake's experimentation with various materials and methods – in this case, he used an initial preliminary layer of chalk and glue. However, the overall aura and effect of the paintings, thankfully, is not lost.

A second version of John Milton's scene from Paradise Lost was also depicted by Blake, now held at National Trust, Petworth House.

Satan Calling Up His Legions

(from John Milton's 'Paradise Lost') c.1805–1809

William Blake (1757–1827)

This depiction of Satan Calling Upon His Legions has survived the tests of time somewhat better than the one held in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, due to the different method Blake used. Once again, this was an experiment of tempera on canvas, but this time Blake used a variety of glazes which were painted on top of gold leaf. The layout is the same, Satan stands atop a rock while the twisting figures of the damned lie around the base but, rather than the blues and greens of the previous, this is bathed with reddish hues and the depth of perspective is far greater. The intricate detailing of the bodies is clearly apparent and further adds to the power of this image.

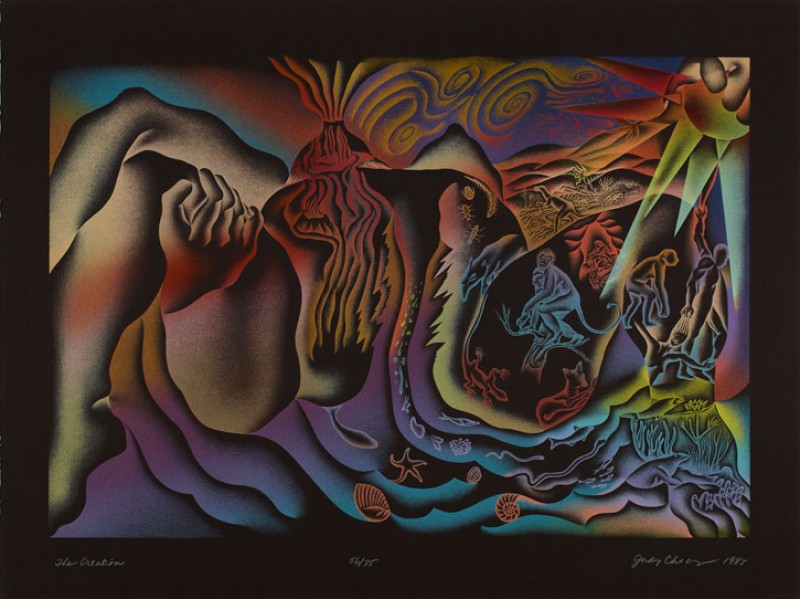

Blake's use of recognised content, whether it be inspiration from mythology, religion or even children's books, allowed him to create works which were simultaneously accessible and shocking – due to their unrelenting critical outlook on society and the issues facing people at the time. These dark, apocalyptic images presented the world with Blake's personal perception of society and the chaos of war surrounding him. Blake's opposition to society's hold over man and its rigid structure – and rules for how people should think and be presented, was something which Blake fought against throughout his career.

Both Blake's art and poetry took on an aesthetic, critical and simultaneously political stance. In addition to drawing on mythological stories and characters of religion, Blake also used to present his own mythological depictions. From a young age, Blake claimed to have visions – seeing angels and spirits amongst nature and the day-to-day. This heavily influenced his artistic practice and was a recurrent theme within his work. Like Blake's subverted portrayals of recognised myths, Blake's personal mythological depictions portrayed the world and humanity as a place filled with sadness and oppression. He had an interest with the seemingly divided characters of man and it was this divided self that Blake regularly focused upon within his oeuvre, using it as a topic of criticism which he felt reflected society.

The Ghost of a Flea was one of Blake's final pieces and perhaps one of his most well-known.

Blake's visions continued throughout his life and his friend John Varley encouraged him to continue drawing them. This particular work depicts a spirit that Blake saw of a flea. According to records, the spirit told Blake that 'all fleas were inhabited by the souls of men'. This perhaps explains the human form that the flea takes on, his muscular body topped with the creepy face of a flea.

This portrayal presents, as with a large proportion of Blake's work, the animalistic, bloodthirsty and sinister characters of humanity, that the artist felt he bore witness to throughout his lifetime. The Ghost of a Flea has even inspired well-known artists today, such as Damien Hirst and Hassan Khan.

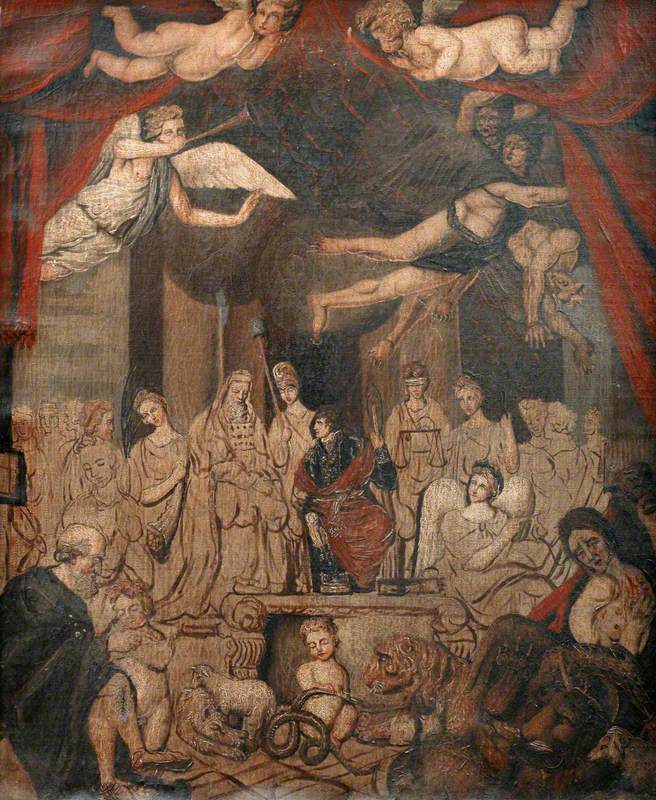

Before his death, Blake had begun a project which he worked on until he passed away. He was commissioned to depict Dante's Divine Comedy. Unfortunately, the few paintings he did complete never made their way to engravings, but the subject matter continues to highlight Blake's own interests and beliefs through their content. An Allegory of Peace is one of the possible surviving templates for this project.

Although it has never been confirmed as Blake's own work, it has been attributed to him, due to the image following Blake's usual style – dark tones and colours surrounding the classically depicted figures.

William Blake died on 12th August 1827, from an unknown disease. The symptoms which Blake described during this period have since been linked to the illness known as biliary cirrhosis – which can be caused by exposure to fumes created when applying acid to copper plates, a method he used for printmaking.

Unfortunately, after his wife's death, the work she had not managed to sell was passed on to Lord Tatham who destroyed numerous pieces due to their political and controversial content.

Thankfully, however, since his death Blake has gathered a prominent and impressive following, influencing numerous artists and writers and finally gaining the recognition he deserves.

Florence Bell, Director of Floga, an independently run organisation which promotes Art History and Yoga in schools and communities