Should you visit the offices of Skipton Town Council, above the Barclays Bank in Skipton High Street, you’ll find a sheep.

Several sheep in fact, looking as relaxed as sheep can, in a painting by Alfred Morris. Judging from the Art UK website, Morris was quite a big name in sheep painting in the nineteenth century (which was itself very big on sheep painting). There’s also a John Charles Morris (active 1851 to 1889) and a John W. Morris (active 1865 to 1924), both of whom appear to

Mrs Mary Cobbold and Miss Cobbold, with a Lamb and a Ewe

c.1752

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

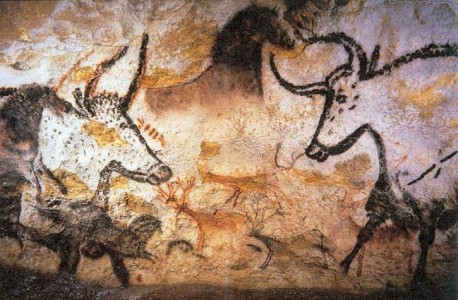

There are a lot of things they aren’t doing, first of all. Because these pictures counter a long artistic tradition in which a sheep is never just a sheep. In a Claude or a Poussin painting they might be elements in an Arcadian landscape, essential to fill out the idyll of the pastoral life (and very useful for giving scale and depth to a landscape). Or they might be emotional set-dressing, as they are in Gainsborough’s Mrs Mary Cobbold with Her Daughter Anne.

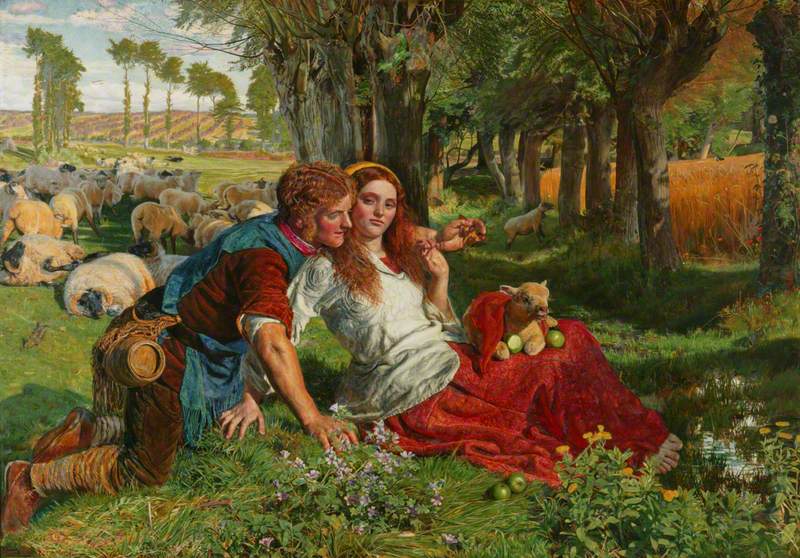

Or they might serve as metaphors: for Christian innocence, for unthinking vulnerability or for the consequences of human distraction, as they do in Holman Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd, in which a shepherd dallies with a maiden (as shepherds tend to do in paintings) while his flock wanders astray in the background. But not here. These are not metaphorical sheep.

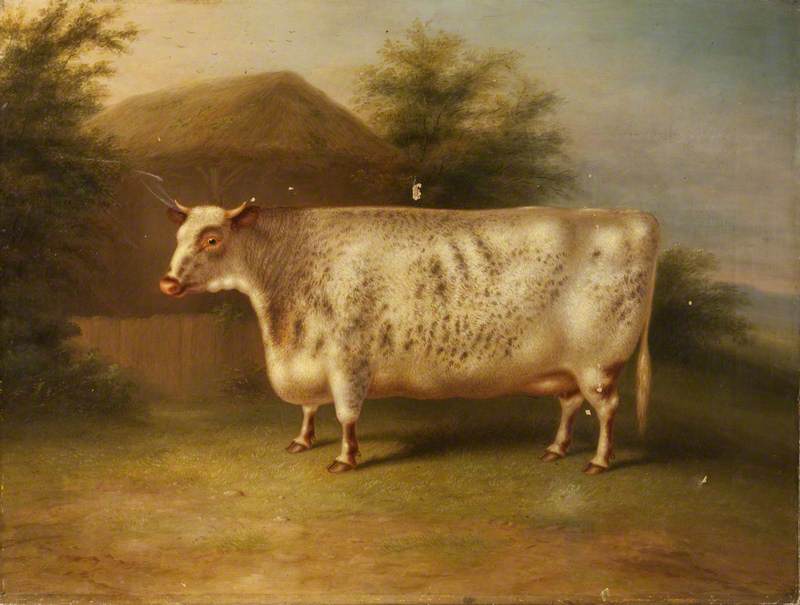

They don’t appear to be exemplary sheep either. Skipton’s Morris painting is quite different from the prolific 'Improvement' paintings of the nineteenth century, which record particularly magnificent breed specimens, often exaggerating the desirable features of the animal to the point of absurdity. In this kind of painting — there are hundreds on the Art UK site — pigs inflate towards the Platonic ideal of a giant sausage on legs, cattle achieve a boxy immensity and sheep turn into giant wooly rhomboids, propped on tiny Q-tip legs (see William Henry Davis’s Prize Sheep in the Museum of Lincolnshire for a particularly ripe example). The livestock in 'Improvement' paintings are often A-list celebrities in their own right (many earned small fortunes for their owners by going on tour). But Alfred Morris’s sheep are crowd-scene sheep.

They are, of course, owned; and you would be able to tell who by from the smear of dye on their heads and fleeces. And they have a job, which is to monetise otherwise unfarmable land by turning it into meat and wool. But if they are representative of anything it is of their own local, familiar sheepiness. Which is, I think, the most winning thing about this particular genre of paintings. They exist for viewers who just can’t get enough of sheep, viewers who can probably see sheep at any time they want just by looking out of a window, but hanker after a practical way of getting sheep indoors so they don’t have to. This kind of viewer doesn't want to think about Virgilian eclogues, or reflect on human waywardness, or brag about their prize-winning New Leicester. And these pictures are here for them. What are these sheep doing? They’re being sheep and that’s it.

Tom Sutcliffe, Arts Broadcaster, BBC Radio 4