Pancake Day: time for some flipping fun. But why?

Possibly you may know that Pancake Day is also known as Shrove Tuesday, or in other parts of the world Mardi Gras (literally 'Fat Tuesday') or Fastnacht. That's because it precedes Ash Wednesday, which in the Western Church is the start of the Christian season of Lent – forty days of fasting leading up to Easter.

Easter itself is the celebration of Jesus's Resurrection and is what is known as a moveable feast, as it does not fall on the same date every year. It's calculated according to the moon and the spring equinox. Counting back forty days (not including Sundays) gives Wednesday as the start of Lent. During the Ash Wednesday church service, the palms used in the previous year's Palm Sunday celebrations (marking the start of Holy Week) are burnt and the ashes are put on believers' foreheads in the sign of a cross.

But what does 'Shrove' mean? It is a version of the archaic English word 'shrive' meaning to do penance and confess your sins, thus leading to absolution (the taking away of that sin). It's about preparing for a time of fasting and contemplation – Lent. And this is where the pancakes come in.

In preparation for the fasting – today rather than fasting it may just be 'giving up something for Lent' – people traditionally used up their stores of fat, butter, milk, flour, etc. It is also probably linked to the last time the food preserved over winter could be eaten before it went bad.

So making pancakes (or similar treats) would be a way of using up the old, but preparing for the lean times to come.

The time of year was sometimes called Shrovetide, and that's the word used in the title of this sculpture.

It depicts three players grappling for the ball during Ashbourne's annual Shrovetide football game, a traditional sporting event that takes place on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday. Like all football games used to be played before it was codified in the nineteenth century, the playing area consists of the Derbyshire town's streets, alleyways and park and river, between 'goals' three miles apart.

Here's another sculpture inspired by a Shrovetide ball game, this time in Atherstone in Warwickshire.

Two characters stand back to back and hold a ball aloft. One of the characters is a child who stands on a pile of books. The child is wearing a hat, reflecting Atherstone's past hat and felting industry.

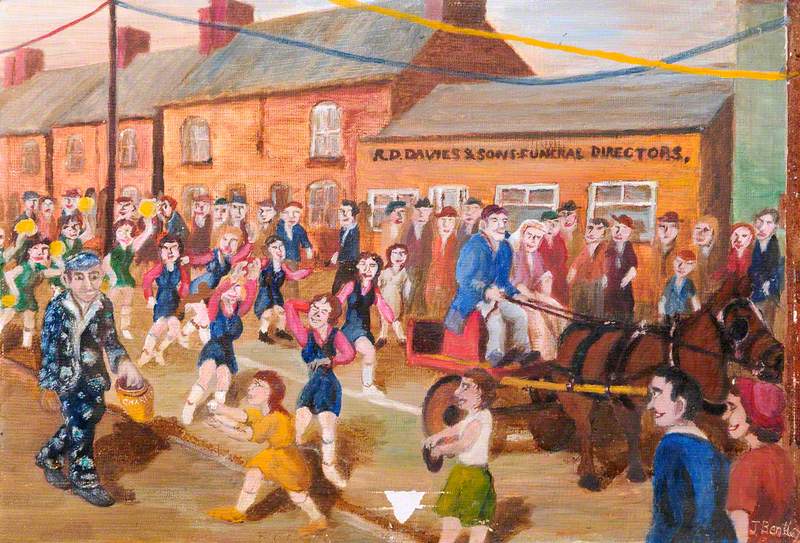

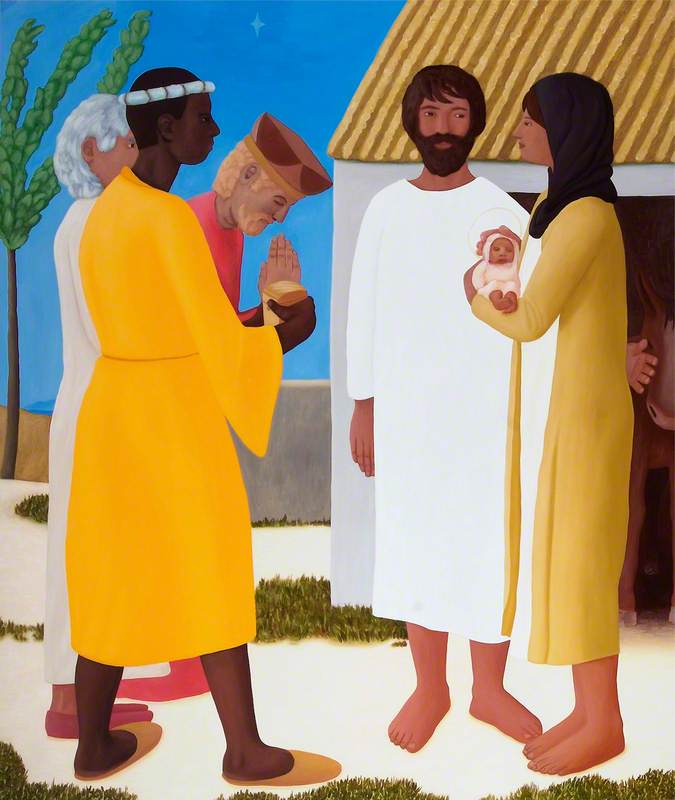

This football 'carnival' picture shows an imagined version of a Shrovetide football game in action.

Football Carnival, Market Place, Kingston, Surrey

Reginald Brill (1902–1974)

This one is in Kingston (now its own London borough) and shows the free-for-all aspect of the game!

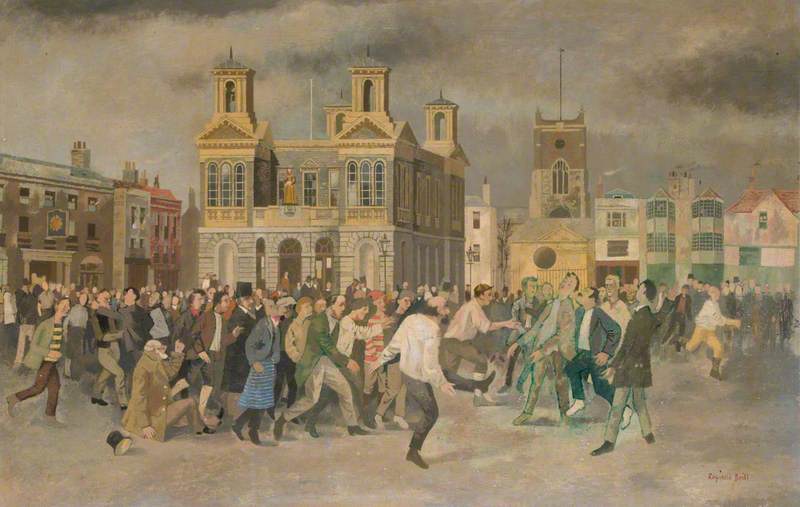

The Shrovetide ball games were traditional in England, but in other parts of the world the time is marked by other festivities.

When you think of the word 'carnival' today, it probably conjures images of bright costumes, a party atmosphere, an outdoor celebration. But what does 'carnival' actually mean?

The word itself is likely derived from 'carne levare' meaning 'remove meat' (or possibly even from 'carne vale' – goodbye to meat!) That's because – like Shrovetide – it was the name of a period of time in the Church's year, leading up to the start of Lent, sometimes beginning weeks or months before, depending on the local tradition.

For centuries carnival (also spelt carnaval or carnevale) was synonymous with the city of Venice. It was celebrated in a number of ways, although like many traditions it is not clear how or when it began. From medieval beginnings, possibly following a Venetian military victory, the festival became an official celebration during the Renaissance. It likely gave the people of Venice a chance to subvert their normal roles, be free of the rigid hierarchy of society and let off steam before the religious piety of Lent.

One of the first events the Venetians held was the Regatta – a series of races along the Grand Canal which had been held annually since 1315 on 2nd February, the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin (also known as Candlemas). This painting by the Venetian artist Canaletto shows the Regatta in the 1730s.

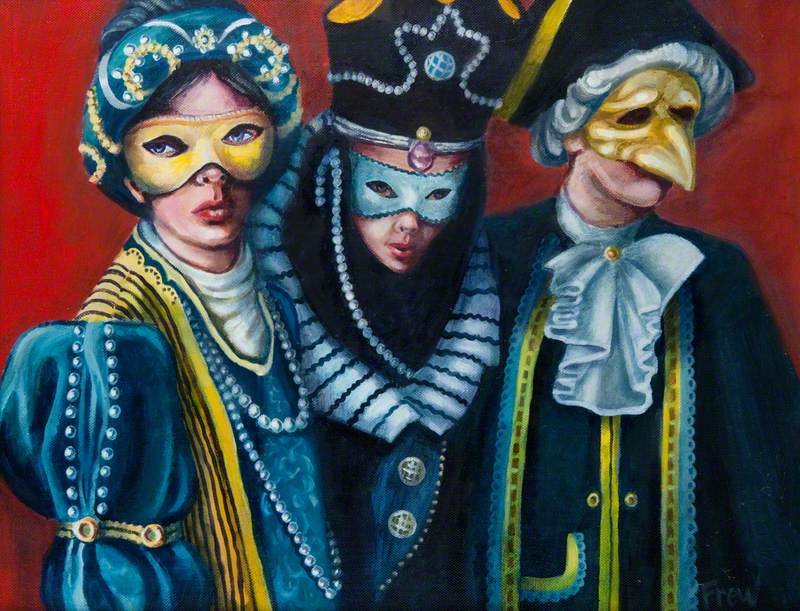

By Canaletto's time, in the eighteenth century, Venetian carnival was famous across Europe and many of the traditions had been cemented. One of the aspects was that many of the carnival participants would wear masks, concealing the identity of the wearer. Some of these became formalised, including the bauta – black capes and white masks, which can just about be seen on some of the figures in the bottom left of Canaletto's regatta picture.

You can get a closer look at the bauta in this striking portrait of Gustavus Hamilton, 2nd Viscount Boyne, drawn by Rosalba Carriera.

Gustavus Hamilton (1710–1746), 2nd Viscount Boyne

1730–1731

Rosalba Giovanna Carriera (1673–1757)

Carriera is often credited with popularising pastels as a medium for finished works, as opposed to just using them for sketches. She was one of the most important portraitists of her time.

Venice also had other celebrations around the end of carnival and the beginning of Lent. Similarly to Shrove Tuesday, they celebrated Giovedi Grasso (Fat Thursday), which took place the week before Ash Wednesday. This painting gives a sense of some of the festivities which took place in the eighteenth century.

Venice: the Giovedi Grasso Festival in the Piazzetta

c.1741–1760

Canaletto (1697–1768) (studio of)

An elaborate stage was built in the square, and you can see acrobats executing a human pyramid. The ropes stretching diagonally across the picture enabled another acrobat to 'fly' from the Campanile (bell tower) to the loggia (box) where the Doge (the ruler of Venice) was watching. The acrobat would recite verses in the Doge's honour and present him with flowers. In the foreground, figures in commedia dell'arte costume (an Italian theatrical tradition) are seen mingling with onlookers and revellers wearing the white masks and black capes of the bauta.

However, despite all the tradition, the Venetian carnival was outlawed in 1797 and although it sporadically reemerged in the nineteenth century, it was revived as a historical tradition only in 1979. Why was it banned? It is likely that the liberties granted to the revellers worried those in charge following the French Revolution and its aftermath, when the French royal family and aristocrats were rounded up and executed...

As well as Venice, carnivals took place in many other cities, and throughout the centuries. For example, this painting shows a Chinese masquerade in Rome in 1735.

The Chinese Masquerade on the Piazza Colonna in Rome during the Giacomo Carnival, 1735

1752

Jacob van Lint (1723–1790)

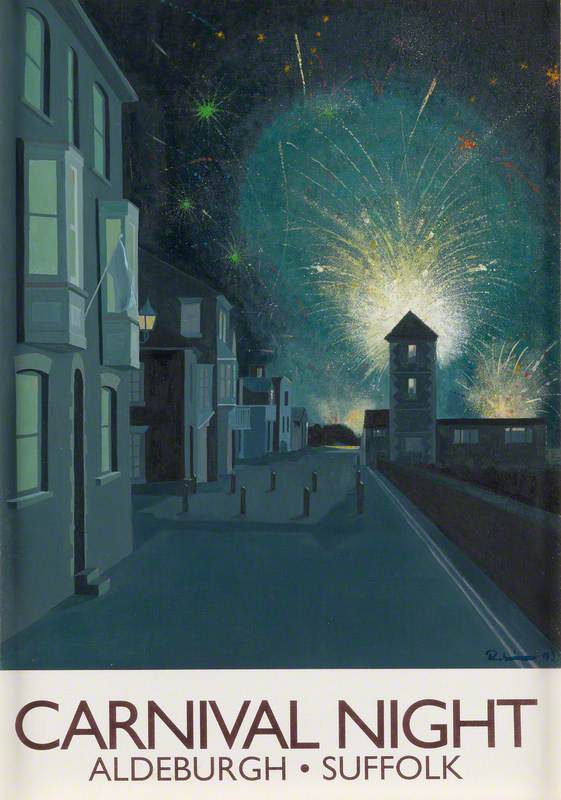

Today, that specific tradition of a carnival before Lent continues across the world – perhaps most famously in Rio de Janeiro and places like New Orleans. However, in the UK, the word has come to mean a festive celebration in a more general sense. This is evident by looking at the titles of some of the 'carnival' works from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Perhaps today the word is most associated with grand street parties and parades like the Notting Hill Carnival, an annual celebration in August. It incorporates some of the Caribbean carnival traditions brought to the UK as part of the Windrush Generation. Although Notting Hill's Carnival may be the most famous, similar events take place in Leeds and Bristol.

Whatever you think about carnival, Shrove Tuesday and Pancake Day, don't forget to enjoy it before the solemn season of Lent begins! The only question left is... what will you have on your pancakes?

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK