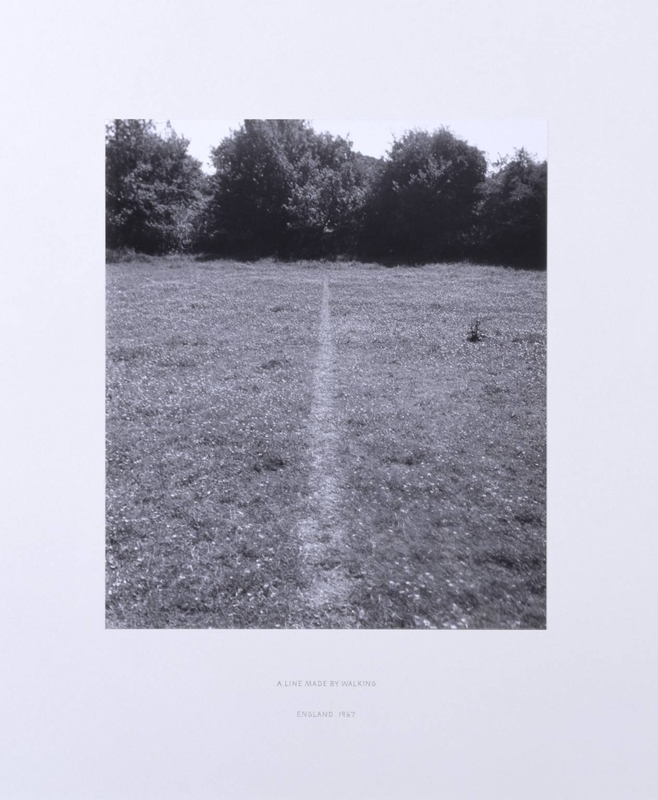

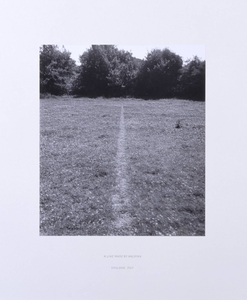

In 1967, Richard Long took himself off to a remote but unremarkable field in southern England, trampled out a line in the grass and photographed the result.

A Line Made by Walking was created while Long was still a student at Saint Martin's School of Art in London. It is the first of his many works made by walking – works in which he takes temporary custody of a place through the soles of his shoes – and it has come to occupy an iconic position in the overlapping histories of land art, conceptual art, minimalism and performance.

Interviewed in his studio near Bristol on BBC Radio 4 a few years ago, the artist reflected on the discovery at the heart of his deceptively simple action: 'It was a path that was a sculpture, it was a sculpture that was a path, and it led to the idea that a journey could be a work of art.'

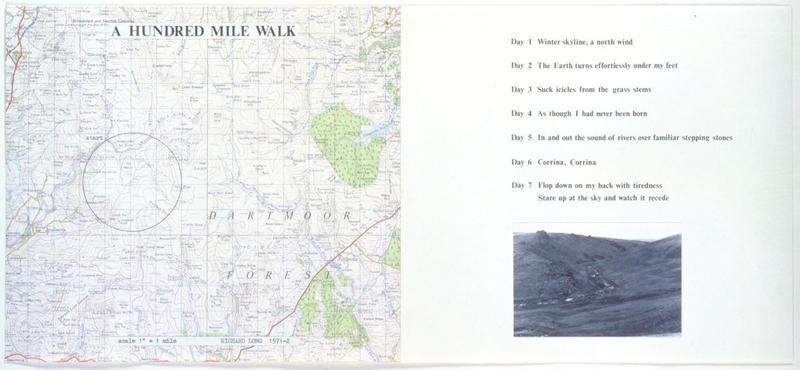

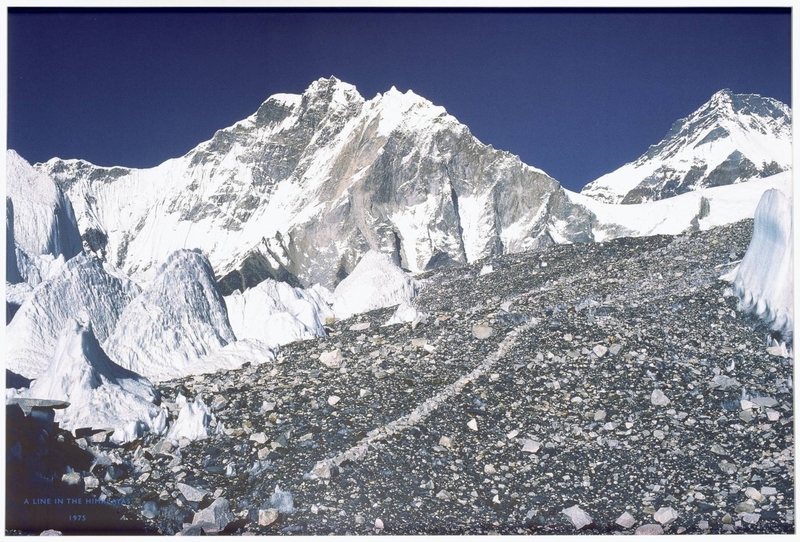

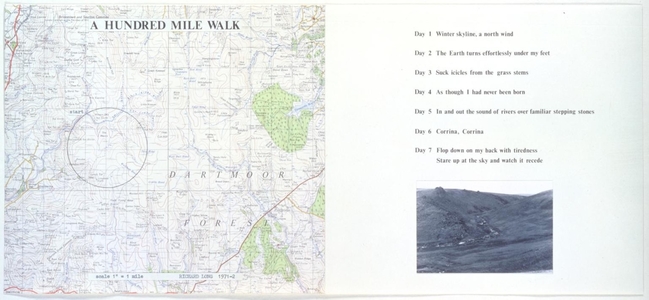

Long has gone on to spend more than half a century interacting physically with the landscape. Documentation of this interaction – its visible manifestation – takes a variety of forms. Some are sculptural, some are drawn; the walking works are variously identified using titles, texts, photographs and maps.

Scratching his presence on the earth is how Zarina Hashmi has described the artist's practice of generating lines and circles by walking – a practice born of a lifelong obsession with movement, space and time. 'My footsteps make the mark,' says Long. 'My legs carry me across the country. It's like a way of measuring the world. I love that connection to my own body. It's me to the world.'

Long's walking works – part pilgrimage, part ritual – draw our attention to the beauty of the world and the power of landscape to nurture the soul. Unsurprisingly, paying attention to that beauty and accessing that power is what a lot of us have been doing on our regular walks during the course of the coronavirus pandemic.

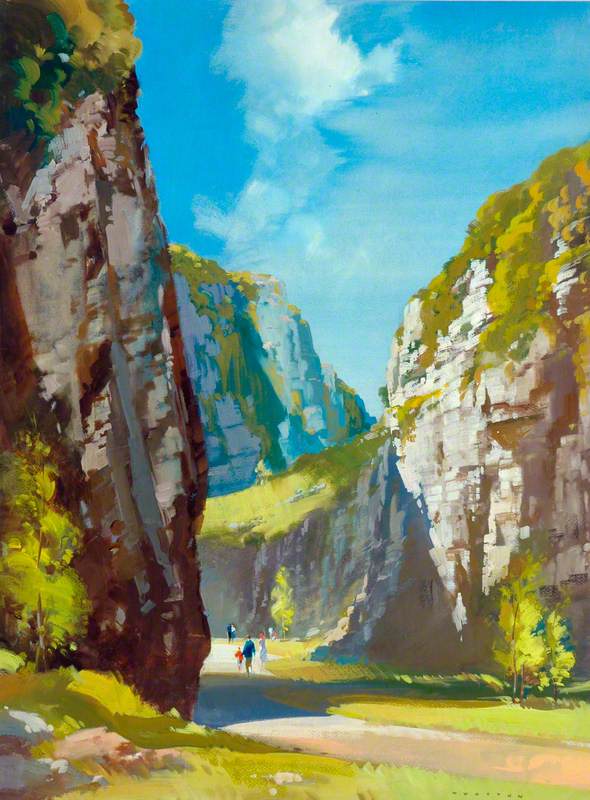

Somerset: Cheddar Gorge

(British Railways poster artwork) 1954

Frank Wootton (1911–1998)

Research undertaken by Sport England shows that walking has become the primary mode of exercise since the start of lockdown. In a recent issue of the Harvard Business Review, Deborah G. Riegel offers up a precise and personal explanation as to why this is so: 'When I think about the simplest and most strategic thing I am able to do for myself that's Covid-safe, it's walking. When I weigh what activity I can do almost every day, with little preparation, minimal effort, no special equipment, and that can contract or expand to fit the exact amount of time I have available, it's walking. When I consider what I can do for myself even when my back pain is flaring up, it's walking. When I want to do something that's good for my mind, body and soul, it's walking. When I want someone's company (physically distanced, of course) – or just want to be alone, walking works.'

Self-evidently we carry our own body weight when we walk so walking constitutes a form of weight-bearing exercise. Walking increases heart and lung fitness, strengthens bones, increases muscular strength and endurance, and reduces body fat. It also enhances our happiness levels. To walk is not just to live, but also to live well.

Of course, the very act of walking has altered dramatically over the last twelve months. As Alan Franks has observed, this was most marked when the first lockdown eased and we ventured out of the front door, hoping to find the old normality.

'It was instantly clear,' says Franks, 'that all had changed, changed utterly. There was a grim comedy to it... The air looked clear enough, and yet everyone had a wariness in their stride and their stare. The confidence had gone from their shoulders. It was as if they could see, a hundred yards away, that fearsome thing, another pedestrian, bearing a dark swarm of contagion around his head, like an evil halo. Pleasant neighbours mutated to lethal units. People – rational-looking people – made extravagant slaloms, right off the pavement and out beyond the parked cars into the centre of the empty roads.'

As any toddler would tell you if only they had the words, walking – especially walking in extravagant slaloms – is a highly developed skill that requires a coordinated effort on behalf of the whole body, with a focus on the feet, ankles, knees, and hips. The cycle of how we walk is called the gait and the gait is divided into two distinct phases. The time a foot is on the ground is called the stance. The motion of the foot away from the ground is called the swing. The stance phase comprises four separate motions from heel strike through big toe push-off, and the swing phase has two characteristics: one being the acceleration into the swing, the other being the deceleration into positioning the heel for the next step.

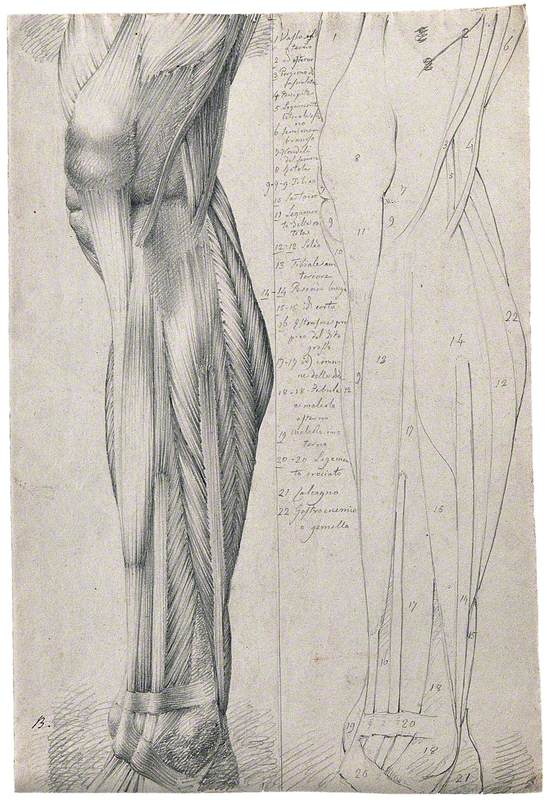

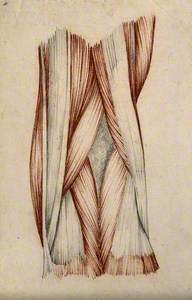

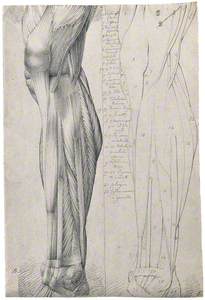

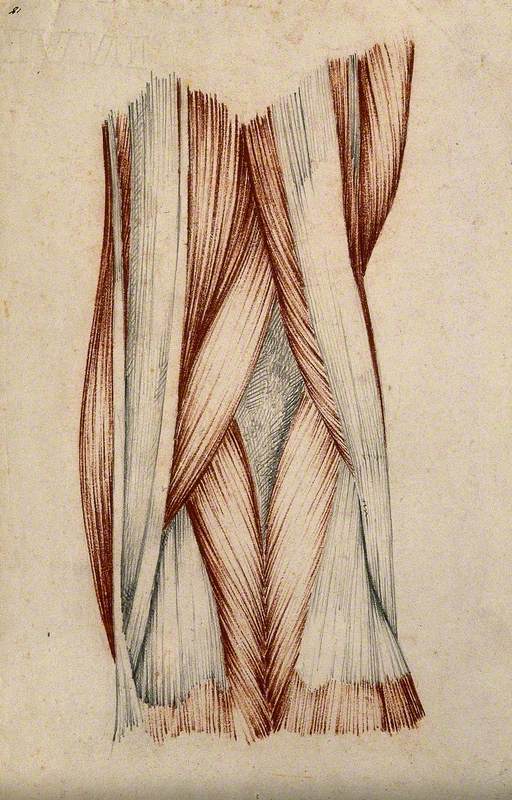

Muscles and Tendons of the Knee Joint

c.1837

Antonio Durelli (active c.1837) (associated with)

Around 200 individual muscles are used in taking a single step forward and we can see a wealth of these in a series of vibrant and detailed drawings by Antonio Durelli at Wellcome Collection in London.

Durelli ran a figure study course at the Milan Academy of Fine Arts in the first half of the nineteenth century and his teaching was predicated on a close reading of human anatomy. Understanding anatomy is key to drawing the human body successfully; of the 28 drawings in the Wellcome portfolio, 16 are devoted to dissections of the feet and legs, and two of these feature hand-written annotations to the underlying structures of the lower leg and foot.

In her fascinating book Anatomy for the Artist, Sarah Simblet confirms that the bones of the lower leg and foot are clothed in numerous muscles, which have evolved to enable us to stand and walk: 'These are bound into layers, groups and compartments to give mass, form and refined movement to the toes, sole, ankle, calf and shin. They assist in maintaining our balance, and give strength, grace and poise to our movement through space.'

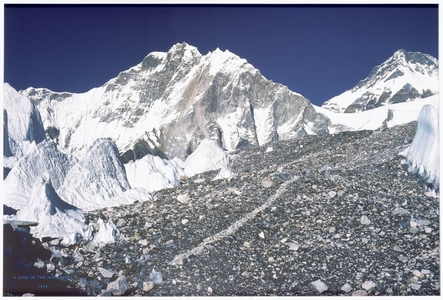

Depicting the movement of bodies through space has preoccupied artists for millennia but, as we have seen, it is only since the 1960s that artists have begun making art out of walking. Richard Long's pioneering discovery that a journey could be a work of art paved the way for any number of walking artists: Hamish Fulton, Vito Acconci, Sophie Calle, Ulay and Abramović, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, Donald Urquhart and Thomas A. Clark, Francis Alÿs, Simon Pope – the list goes on and on.

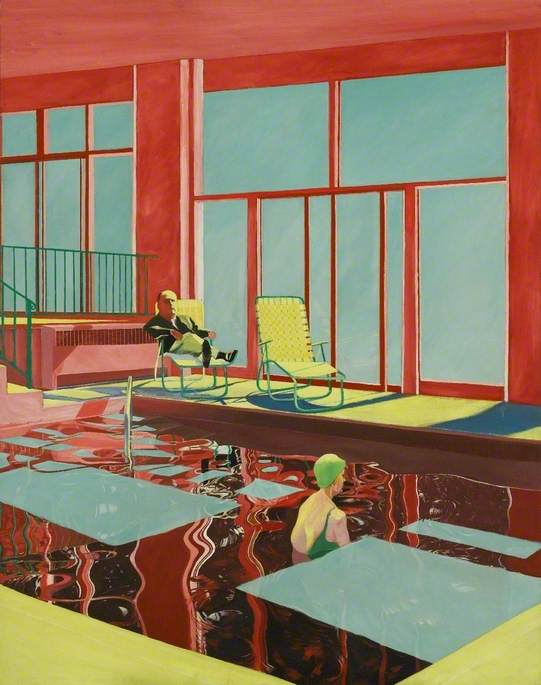

Six Landscapes (Blue)

(right section) 2009

Donald Urquhart (b.1959) and Thomas A. Clark (b.1944)

Of particular note is the Walking Artists Network. The network was inaugurated in 2008 at a meeting of like-minded practitioners at London Metropolitan University, and it is directed at anyone who identifies as a walking artist and everyone who is interested in walking as a mode of art practice. Conferences, symposia and other events have brought walking artists and researchers together to highlight the diverse forms and methodologies that might be defined as 'walking art'.

Walking Artists Network was awarded funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council in 2011 to support its further development, and over the subsequent decade it has organised meetings to coincide with the Sideways festival of walking in Belgium and Footwork conventions in England and Wales.

How the pandemic will play itself out in the work of the Walking Artists Network and artist-walkers more widely remains to be seen, but spare a thought for those people for whom walking during lockdown has been less of a pleasure and more of an ordeal.

In a wickedly funny essay in The Guardian, Monica Heisey skewered the unalloyed drudgery of going for a coronavirus-restricted walk, whatever the benefits: 'What I understand, after almost a full year of rotating lockdowns, during which I have gone on a little mental health stroll almost daily, is that I actually just like having somewhere to be... Touring a new city on foot? A joy. Walking to the bus in the mornings? A lovely private moment before the day's work begins. Strolling to dinner with a friend on a summer evening? I can think of nothing better. But joylessly trudging around the same bit of my neighbourhood, for the fourth day in a row, in the interests of scavenging a crumb of mental health? Thanks, but no.'

Paul Bonaventura, independent producer and curator