Sisterhood is powerful, goes that famous Second Wave adage, a rallying cry grown stale in the intervening years, a metaphor that has ossified into something closer to cliché than any real accuracy. What does sisterhood even mean in this age of commodification, when it's used to sell anything from apps to pop music?

But in its most literal interpretation, there's some truth to this slogan: there is a power, a creative fecundity that exists between siblings, between sisters, a kind of 'musedom' that is more often overshadowed by the kinds found between friends or lovers. For no one is this more true than for Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf, those Bloomsbury stalwarts who painted and wrote and collaborated with each other out of a rich sense of both rivalry and love.

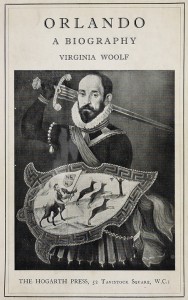

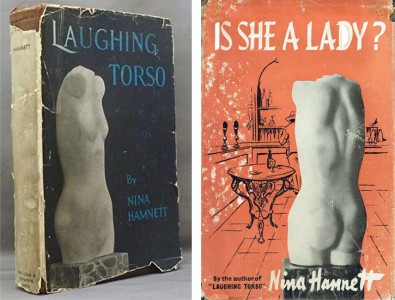

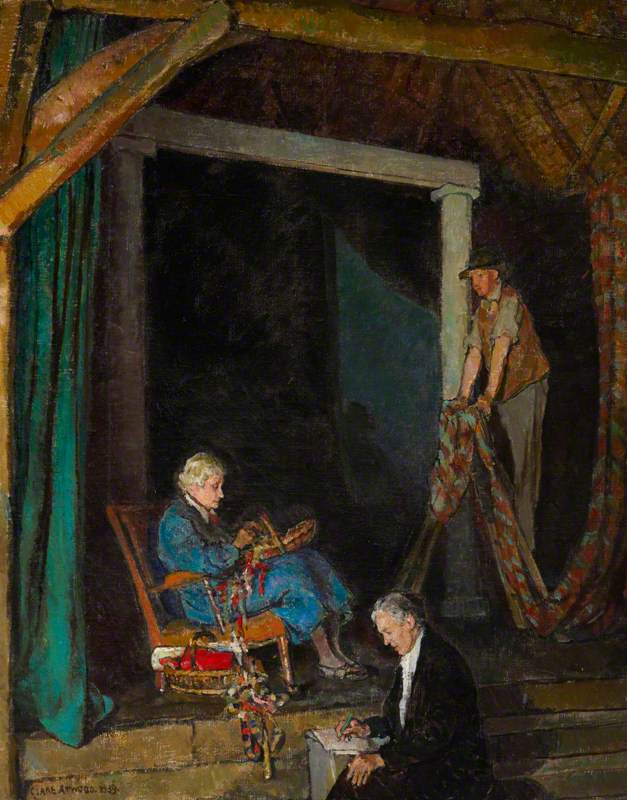

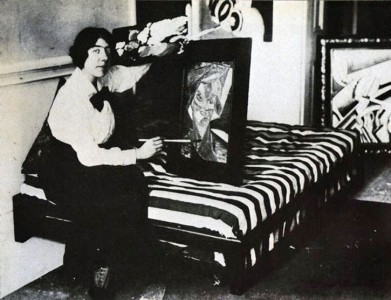

Vanessa was the elder, and as children, the two had idly constructed some kind of pact between themselves that she would be the painter, and Virginia the writer. And so it unfolded: Vanessa created covers for nearly all of Virginia's books, while Virginia sat as a model for some of Vanessa's paintings.

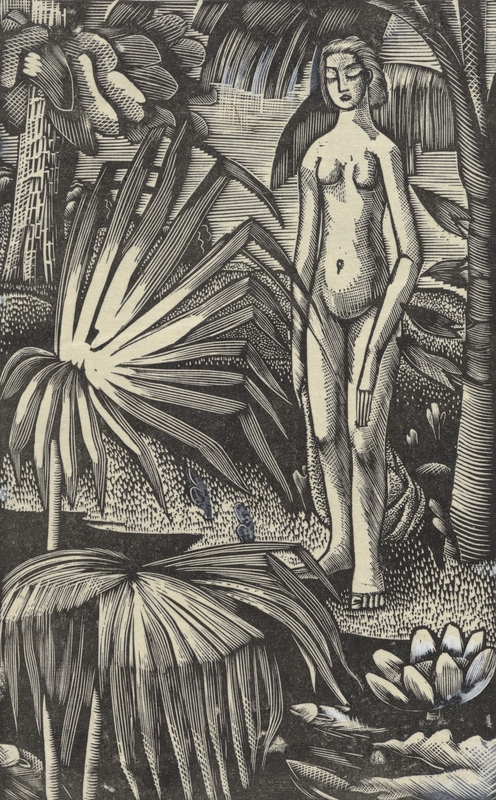

Occasionally, they collaborated: limited editions of Virginia's 1919 short story Kew Gardens, for instance, are replete with loopy, elegant illustrations from Vanessa, as though the manuscript itself was a series of letters, of secrets, passed back and forth between the two.

Virginia Woolf

— Beinecke Library (@BeineckeLibrary) July 17, 2021

Kew gardens. With woodcuts by Vanessa Bell. Hogarth Press, 1919.

More images: https://t.co/NkWUhwLvHe pic.twitter.com/1uDmWZyUtR

Their actual letters to and from one another are lively: sometimes joking, sometimes heated, sometimes mean, sometimes loving, sometimes doleful. They are infused with the kind of implicit love, the thrum of annoyance, which colors the relationships of those who have known each other for all, or nearly all, of their lives. Nicknames pepper the pages. Virginia, writes Virginia's famed biographer, Hermione Lee, was Billy (as in goat) or Ape, while 'Vanessa was Tawny or Maria or Marmot, or, more lastingly, Dolphin.'

'Virginia's lifelong courtship of Vanessa,' observes Lee, 'was licensed by the invention of the pleading, greedy creatures she kept in play all through their correspondence.' A classic younger sister's attitude!

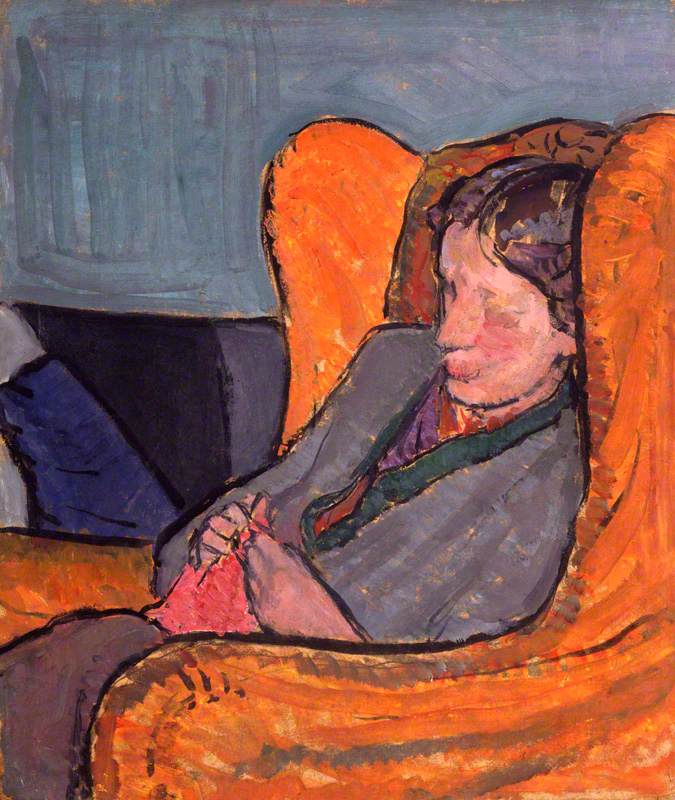

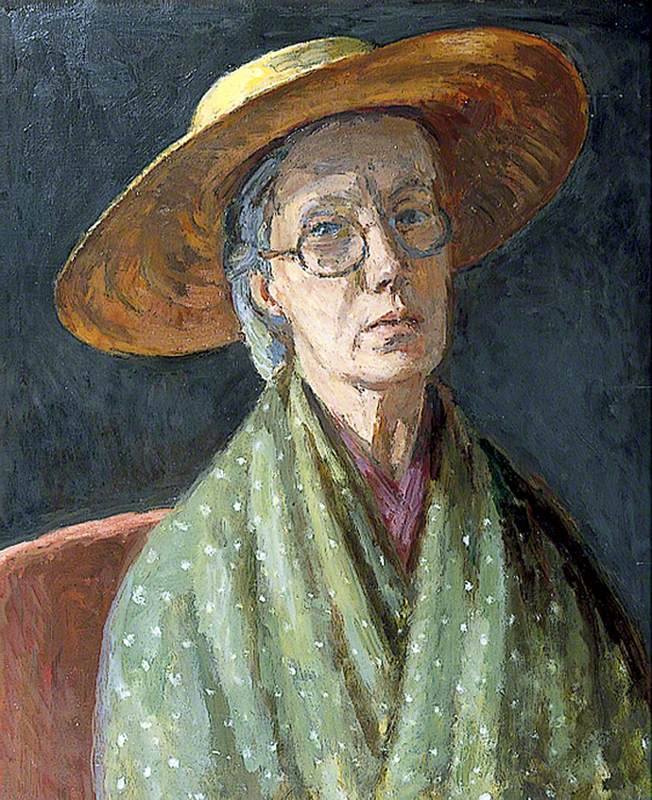

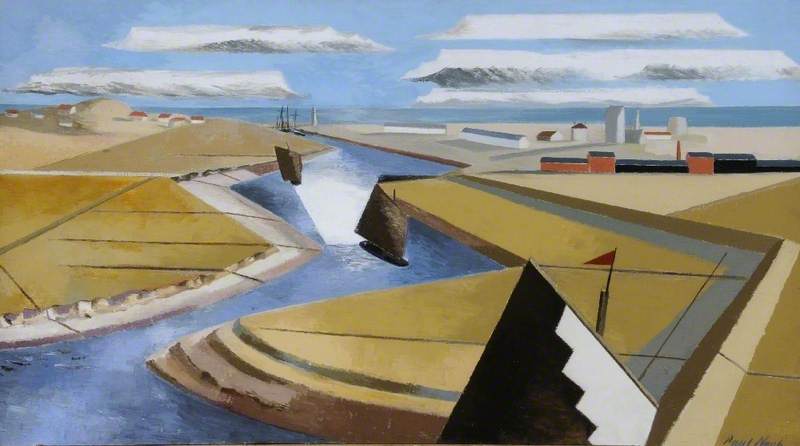

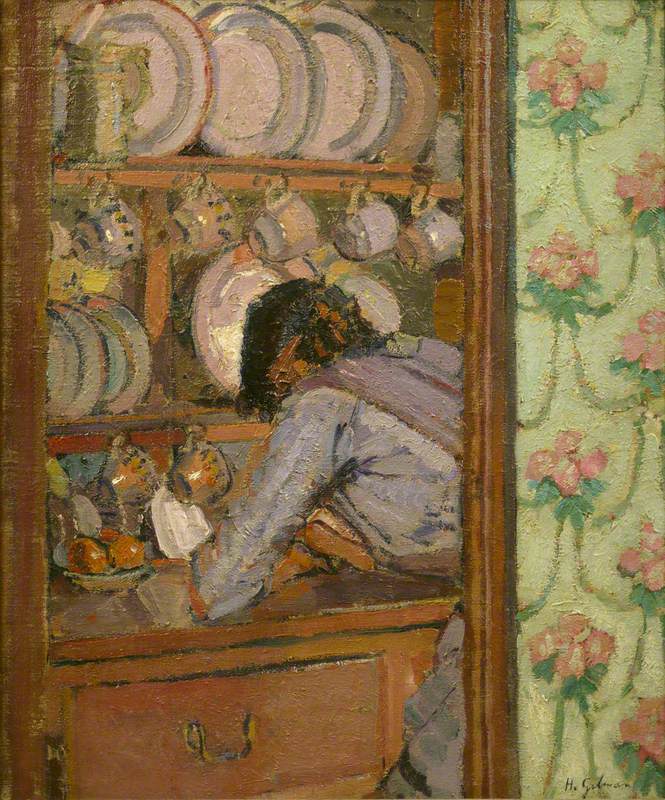

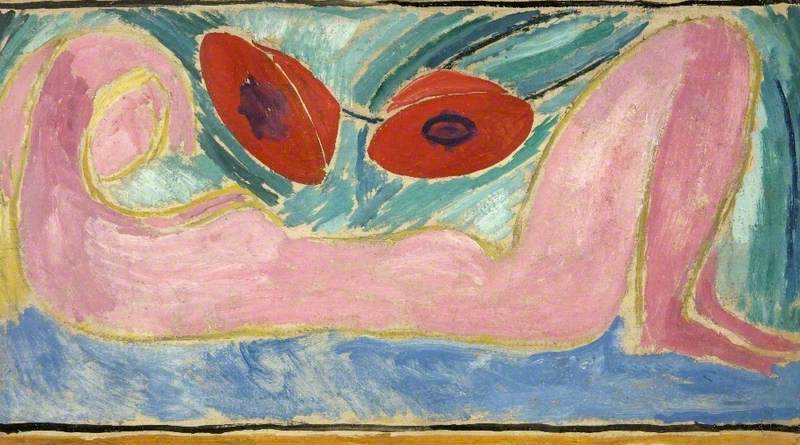

Vanessa was the wife, the mother, of the two, and in the intervening years since her death this has somewhat overshadowed her artistic legacy. But her paintings are winsome, sly, French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism as filtered through an English gaze. In 1912, she would paint the famous portrait of her sister that now hangs in London's National Portrait Gallery.

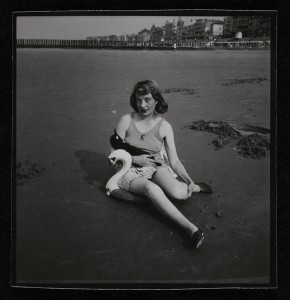

It's a study in human character, the kind her sister would declare changed 'on or about December, 1910.' In the portrait, it is two years later: the heavy fabrics and dark shadows of their Victorian childhoods have given way to Modernist light and color. The subject herself is faceless, the features blurred, more a suggestion of a face than any real likeness. The effect is one more of subjectivity than the relentless Victorian need to categorise.

'How little we know even about brothers and sisters,' Virginia wrote in A Sketch of the Past, her 1939 autobiographical essay written about herself and the early Bloomsbury Group. In Vanessa's portrait of her sister, we do not know this woman sitting there, we cannot see her face. She is intimately rendered, and yet remains a mystery: this is the experience of sisterhood as translated into paint.

Lily Briscoe in To the Lighthouse was loosely based around Vanessa. How did Vanessa feel when she read her, how did Virginia feel when she saw Vanessa's painting? The last line of the novel: 'Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.' In Vanessa's paintings of her sister, we see her vision at its most fully realised.

Rhian Sasseen, writer