Joseph Mallord William Turner is acknowledged as instrumental in establishing a modern school of British art, especially in making landscape painting a worthwhile artistic genre in its own right.

His influence was vast, during his life and after. However, this Curation specifically examines Turner's significance for Norwich School artists of the early-mid 19th century.

In 2019, thanks to grants from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the Art Fund and a private donor, Norfolk Museums acquired our first oil painting by Turner, Walton Bridges. This has given us opportunities to explore how Norwich artists such as John Sell Cotman, John Crome and many others were inspired by Turner's ground-breaking approach to subject and technique.

-

The Norwich Society of Artists

The Norwich Society of Artists was founded in 1803, the earliest of its kind outside London. Coalescing from the thriving artistic activity in the city, it was the first regional society to follow the example of the London-based Royal Academy, raising the status of fine art by offering a forum for support, criticism, discussion and exhibition. Its subject matter focused on landscapes, especially of Norfolk, mainly observed en plein air in the modern manner.

Influenced by the RA, and clearly aware of the work of Turner, but also independent, Norwich School artists included John Crome and John Sell Cotman and also other notable though lesser-known names. Their work comprised both local and national concerns in contemporary art.

-

Walton Bridges

Walton Bridges 1806This was painted during one of Turner's many trips on the Thames. Made from direct observation, it exemplifies Turner's artistic concerns early in his career. It also ties in with the aims of the Norwich School artists: to experience the landscape in depth.

This intense focus on nature reflected contemporary Romanticism, which glorified emotional responses to the natural world, especially its most spectacular aspects, whether these were purely enjoyable like sunsets, or had a frightening, dangerous side, like avalanches or storms.

Turner portrayed nature's timeless beauty, but contrasted this with scenes of everyday life and modern commerce, as seen here. He engaged fully with both the sublime and the mundane, showing them in coexistence.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on canvas

H 92.7 x W 123.8 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

The Thames near Walton Bridges

The Thames near Walton Bridges 1805Wherever possible Turner worked en plein air. This work and its companion Walton Reach were probably painted on board his boat on the Thames. It was typical of Turner’s approach to make several versions of the same scene, from different angles, seasons or times of day, to capture the essence of how the changes in light and shadow altered the atmosphere of a place.

Working so much in the open air was new and inspirational for many artists of the time, including those of the Norwich School, for whom observing local Norfolk landscapes was a central part of their practice.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on mahogany

H 37.1 x W 73.7 cm

Tate

-

Walton Reach

Walton Reach 1805This spontaneous oil sketch, like the previous work, was painted during the same period as the more finished picture Walton Bridges now at Norwich Castle. From 1804 onwards, Turner had houses on the Thames, at Isleworth and Twickenham, not far from Walton, enabling him to paint from the closest possible vantage points.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on mahogany veneer

H 36.8 x W 73.7 cm

Tate

-

Dolbadern Castle

Dolbadern Castle 1800The Napoleonic wars meant that artists were unable to visit Europe, and had to confine their travel to the British isles. Turner went abroad when he was able, but British landscape was his first focus, and he made extensive sketching tours around the UK early in his career.

He first visited Wales in 1792, and enjoyed its mountains, rivers and magnificent ruined castles, which exemplified perfectly the current ideas about Romanticism and the ‘Picturesque’. Welsh scenery inspired many of his most influential early paintings. Several of his Welsh landscapes were shown at the Royal Academy, including castles such as Dolbadern. This picture, shown in 1800, was much admired, and was accepted as his Diploma work for election as an Academician.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on canvas

H 119.4 x W 90.2 cm

Royal Academy of Arts

-

Barmouth Estuary

Barmouth Estuary 1801Cotman went to Wales early on in his career and, like Turner before him, was inspired by what he saw. When he started showing at the Royal Academy in 1800, several of his first exhibited watercolours at the RA were Welsh landscapes and ruins, clearly influenced by Turner.

Here Cotman depicts Barmouth estuary in soft, moody colours, reflecting the changeable Welsh climate. Like Turner, though the place is clearly recognisable, he captured the atmosphere of the location more than its precise topographical details. Turner had drawn a very similar view of this estuary from almost exactly the same point, with Cader Idris behind it, on his own trip to Barmouth in 1798.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Pencil, watercolour & gum arabic

H 17.4 x W 28.8 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

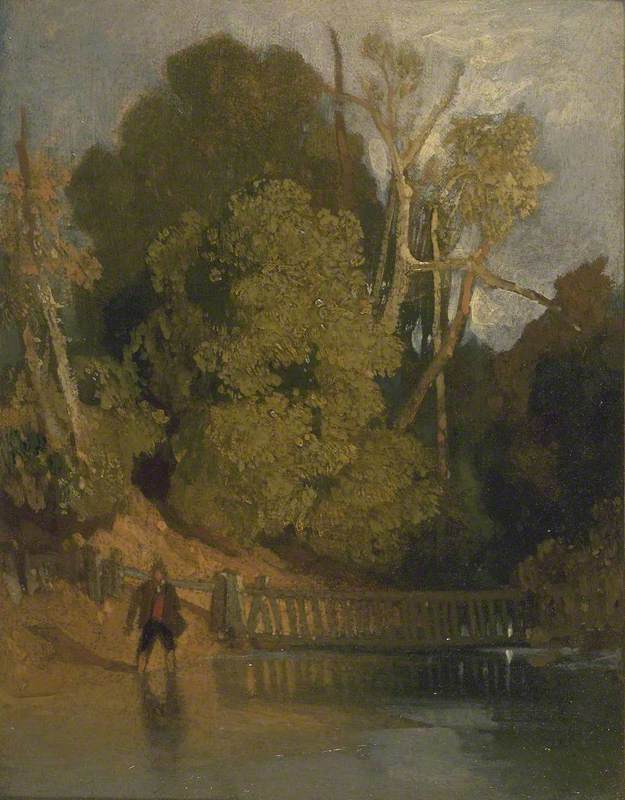

Norwich River: Afternoon

Norwich River: Afternoon c.1812–1819Part of Turner’s artistic make-up from the start was his consistent engagement with modernity. He did not confine himself to imaginary, classical landscapes but portrayed real places and people, and contemporary technology, as we see in Walton Bridges.

Like Turner, John Crome also juxtaposed the ideal with the real. In this view of Norwich’s river, the Wensum, the mellow beauty of a summer afternoon is combined with a portrayal of workers’ cottages in a poor part of the city. Close observation shows unglamorous details: washing on the line, and the houses in disrepair. Many tannery workers lived here, and the louvred gable visible in the background may be a drying loft, possibly for the tannery complex on nearby Heigham Street.

John Crome (1768–1821)

Oil on canvas

H 71 x W 99.5 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

On the River Yare, Norfolk

On the River Yare, NorfolkWalton Bridges was bought by Sir John Leicester in 1807. He was a very forward-looking collector, who led the way in collecting contemporary British art. Unusually, Leicester maintained a gallery of modern British art in his London home, open to the public. Artists like Crome and Cotman probably saw Turner’s work here.

Leicester also bought George Vincent’s work. Vincent, although he trained with John Crome in Norwich, spent most of his career in London, exhibiting at the Royal Academy several times alongside Turner. His portrayal of the Yare, seen here, showed the differences between London and Norwich in the volume of river traffic at the time, although he also includes a mix of serene rural scenery and working life.

George Vincent (1796–1831)

Oil on canvas

H 87 x W 112.7 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

A Small Dutch Ship Riding out a Storm

A Small Dutch Ship Riding out a Storm late 17th C–early 18th CBy Turner’s time, there was already a strong British tradition of sea painting. The navy was prominent in cultural and political life, so there was great interest in maritime art, especially in realistic portrayals of shipping.

Willem van der Velde the Younger had been key to establishing marine painting’s importance in England. Charles II admired the genre, so invited van de Velde, and his father, Willem the Elder, over from Holland in 1672. Turner was strongly influenced by the Younger Willem, whose work was renowned and emulated long after his death. One of Turner’s first major commissions was for a seascape to complement a work by van der Velde in the Duke of Bridgewater’s collection.

Willem van de Velde II (1633–1707)

Oil on canvas

H 76.2 x W 63.5 cm

National Maritime Museum

-

Fishermen at Sea

Fishermen at Sea exhibited 1796Turner had a lifelong love of water, and of boats, and from an early age had been inspired both by the river Thames, and the sea.

The first oil painting he showed at the Royal Academy was this seascape. Though influenced by earlier Dutch art, it emphasises the drama of humans struggling against the elements. This is combined with an accurate rendition of the fishing vessels, an extraordinary ability to convey the sea’s depth and power, and capture the atmospheric glints of its moonlight reflections on the choppy surface. This and comparable early seascapes were very popular and were highly influential on other artists.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on canvas

H 91.4 x W 122.2 cm

Tate

-

After a Storm

After a Storm 1820sCotman first encountered Turner’s art by copying works by him at Thomas Monro’s drawing academy, which, upon moving to London, Cotman attended from 1799.

Cotman both admired and envied Turner’s work and success. He did several pictures along similar lines to Fishermen at Sea. Seascapes offered numerous possibilities to explore movement, texture and colour in sky and water, as well as showing man battling the fierce forces of nature.

This work focuses on the unpredictable nature of the sea, the moment when sun breaks through dark clouds, illuminating the boats and fishermen who have survived the storm. Like Turner, Cotman aimed to capture the essence of the atmosphere during this process of change.

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Oil on canvas

H 63.2 x W 75.6 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

Moonlight, a Study at Millbank

Moonlight, a Study at Millbank exhibited 1797Seventeenth century Dutch artists, such as Aert van der Neer, had first popularised the ‘nocturne’ as an artistic genre, and it was greatly admired in Turner’s time. It harmonised with contemporary aims to engage with nature in all its many forms.

This early work by Turner portrays boats on the Thames, but by setting it at night, he has used this opportunity to transform what would normally be a prosaic scene into something mysterious and magical. He explores the effects of subdued light with a rich, dark colour palette, highlighted with touches of bright white from the moon and star and their reflections.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on wood

H 31.4 x W 90.8 cm

Tate

-

View from Yarmouth Bridge, Norfolk, Looking towards Breydon, Just after Sunset

View from Yarmouth Bridge, Norfolk, Looking towards Breydon, Just after Sunset c.1823–1825Maritime scenes at night gave an artist scope to create a variety of rich chiaroscuro effects of moonlight and shadow. The genre of the night seascape, first popularised by Dutch artists, was later enthusiastically emulated and developed by both Turner and others in Britain.

Here Cotman’s view from Yarmouth Bridge uses the evening half-light to create a scene of soft blurred outlines and shimmering water, its dreamy atmosphere suggesting the approach of night. Contemporary critics noted a clear influence from Turner in this picture, although, since Turner was sometimes seen as excessively ‘modern’ this was not always an expression of approval!

John Sell Cotman (1782–1842)

Oil on millboard

H 44.5 x W 63.4 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

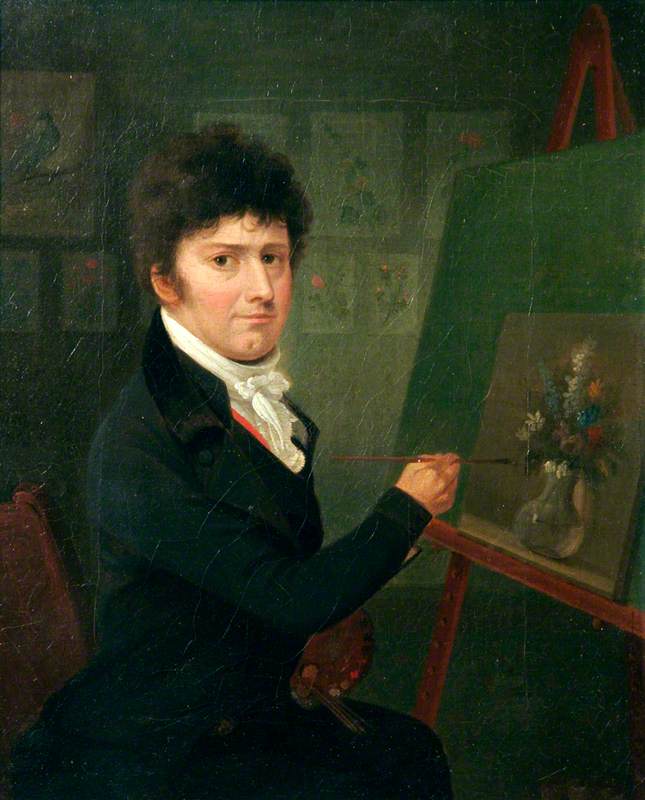

Seascape in Moonlight

Seascape in MoonlightNorwich School artists were, like Turner, very familiar with seventeenth century Dutch painting, particularly because of the long-standing cultural closeness of Norfolk to the Low Countries and the geographical similarities in the landscapes.

Several Norwich artists engaged with the night seascape genre, including James Sillett. He lived in Norfolk and London and exhibited at the Royal Academy throughout his career, beginning in 1796, the same year as Turner. In this painting, the luminous night sky, the vista stretching out to a seemingly infinite distance with moon reflections leading the eye, the ships, some misty and indistinct, some sharply silhouetted, show clear stylistic debts to both Turner and to Dutch antecedents.

James Sillett (1764–1840)

Oil on canvas

H 45.5 x W 68.7 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

Seascape (Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland)

Seascape (Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland)Turner covered the subject of this dramatic Northumbrian castle many times, although only visited the place once, on an early tour of Britain in 1797. Turner exhibited an oil at the RA in 1798 which is now in Victoria, Australia, but it was later also engraved in his Liber Studiorum. Henry Bright was much younger than Turner but became a friend of the older artist and sometimes travelled with him in Europe, painting similar scenery.

Though Bright’s version of Dunstanburgh is not a direct copy, the castle appears in the same aspect, high up on the left, and with a rough sea below. Whether Bright visited this site himself or not, he would have been inspired by this most romantic of landscapes.

Henry Bright (1810–1873)

Oil on canvas

H 61.4 x W 109.7 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

Frosty Morning

Frosty Morning exhibited 1813One of Turner’s techniques which was considered very modern and unusual was to use a light- coloured ground layer, as opposed to the darker grounds customary at the time. This made the backgrounds of his paintings more luminous.

In this work, Frosty Morning, Turner has used this type of ground, where it functions to convey an evocative rendition of the pale light of a winter’s day. The naturalism of this scene was much acclaimed.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on canvas

H 113.7 x W 174.6 cm

Tate

-

Road with Pollards

Road with Pollards c.1815John Crome also adopted Turner’s habit of using pale coloured grounds for his canvases. Here, in Road with Pollards, painted a couple of years after Frosty Morning, he has created a similar effect of cool wintry daylight, and has also employed comparable compositional devices, with bare trees and a path winding off into the distance. Figures and animals inhabit a highly atmospheric if undramatic rural landscape.

John Crome (1768–1821)

Oil on canvas

H 75.8 x W 101.7 cm

Norfolk Museums Service

-

Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba

Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba 1648Claude Lorrain was an enduringly important artist for Turner. His classically-inspired landscapes, often harbour scenes, usually incorporated a central distant point of dazzling sunlight, casting a long reflection in rippling water.

Two major paintings by Claude, including this one, came to England in 1800, and went on public display. Turner saw them and was moved to tears by their beauty. He used Claude's approach to light and shadow many times in his own work. He also absorbed Claude’s ability to create magnificent, sweeping vistas, which lead the eye onward as if the perspective is extending endlessly into the distance, as if the heavens are opening, or the awe-inspiring sublimity of nature is being revealed.

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682)

Oil on canvas

H 149.1 x W 196.7 cm

The National Gallery, London

-

Sun rising through Vapour: Fishermen cleaning and selling fish

Sun rising through Vapour: Fishermen cleaning and selling Fish before 1807Turner would have been working on this painting at the same time as Walton Bridges. It was also bought by John Leicester in 1807. It is clearly inspired by Claude's work, with its sunlight softly sparkling as it reflects up from the sea, and its sense of great distance as the viewer’s eye is led out towards the horizon.

However, while Claude focused on grand classical themes, Turner brings his subject up to date. In the foreground groups of fisherfolk are gathered. There may be a humorous touch intended here: ignoring the sublime beauty of the seascape, they are focusing on mundane but vital daily tasks of cleaning and preparing their catch.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Oil on canvas

H 134 x W 179.5 cm

The National Gallery, London

-

Gorleston Harbour, Norfolk

Gorleston Harbour, Norfolk 1848Here, Alfred Stannard is using stylistic devices borrowed from both Turner and Claude. The soft light suffuses the whole scene with a serene, dreamy glow, the line of the sun reflected in the water leads the viewer’s eye into a seemingly infinite distance towards the horizon. Stannard was 30 years younger than Turner, (born the same year as Walton Bridges was painted) but the influence of both Claude’s and Turner's approaches to light is clear in this work.

Like Turner, he is also combining an emphasis on the sublime beauty of nature, with a much more down-to-earth focus on the local fishermen and their everyday activity.

Alfred Stannard (1806–1889)

Oil on canvas

H 81.2 x W 112.4 cm

Norfolk Museums Service