While Harold Gilman is best known as one of the founders of the Camden Town Group of twentieth-century English painters, it is one of his earlier paintings at York Art Gallery that has caught my eye.

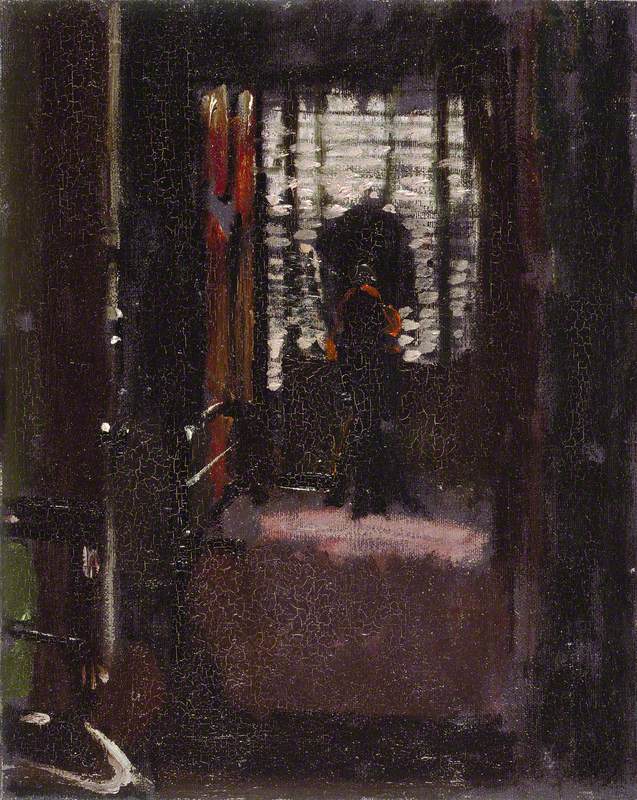

In it, two little girls sit together in an armchair by a window. They have flushed cheeks and tight rosebud mouths, and both wear big floppy ribbons in their hair in the style common to Edwardian girls. One holds a doll; the other has on red mittens. Their legs dangle high above the floor; they look marooned in the chair, unable to get down. They are painted with loose impressionistic brushstrokes, but the shapes of their faces are clear, and they look like sisters – the younger (Hannah) on our left, the older (Elizabeth) on our right. They are not looking at us, but to the side, as if listening to something or someone in another room.

It is their eyes that most draw me in. Hannah looks both solemn and quizzical; Elizabeth has pinched, dark, sad eyes, almost dog-like in their melancholy.

The painting includes potential points of light – literally – to counteract the sense of wistful anxiety. Sunshine is flooding through the window, lighting up the wall, the doll's dress and the length of the chair's arm. Tellingly, the girls are not playing with the doll; it is waiting for attention, just as they are.

When children wait like this, it is usually for adults – to finish what they are doing, to take notice, to take charge. Likely their mother is somewhere nearby, going about her business while the girls wait for her and their father paints them. They are being incredibly patient, and I suspect no one will thank them for it.

When I look at paintings I try not to dwell too much on the biography of the painter (with one notable exception – that is exactly what I did with Johannes Vermeer in my novel Girl with a Pearl Earring). However, with these

He painted it in 1906–1907, and in

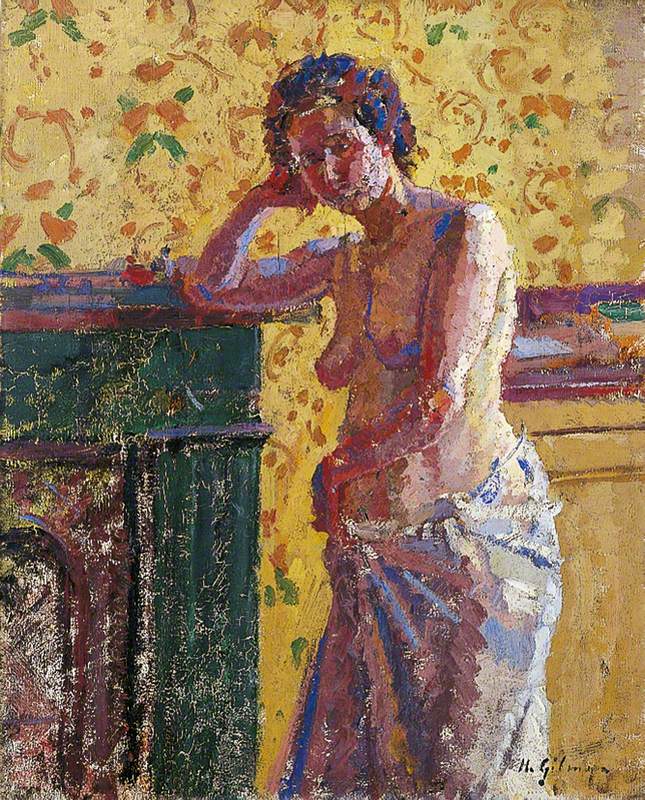

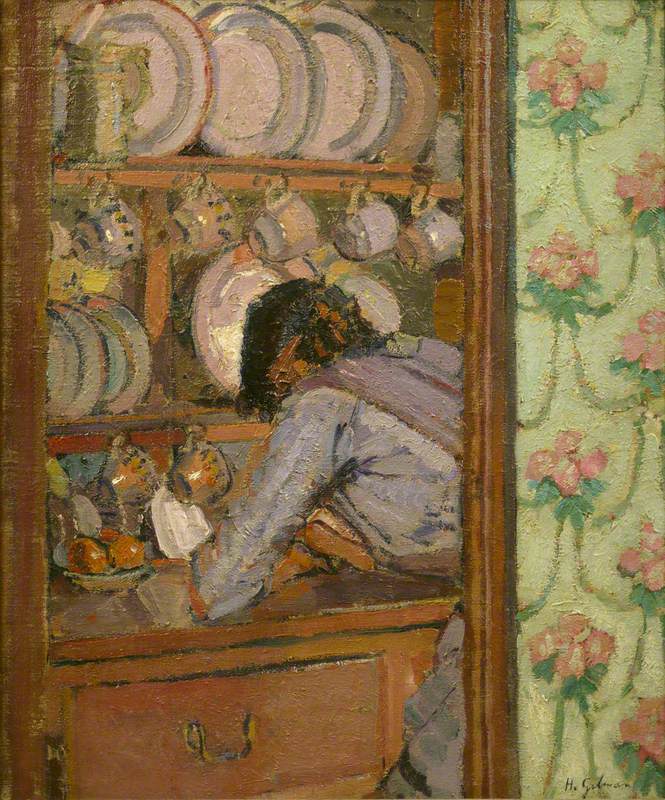

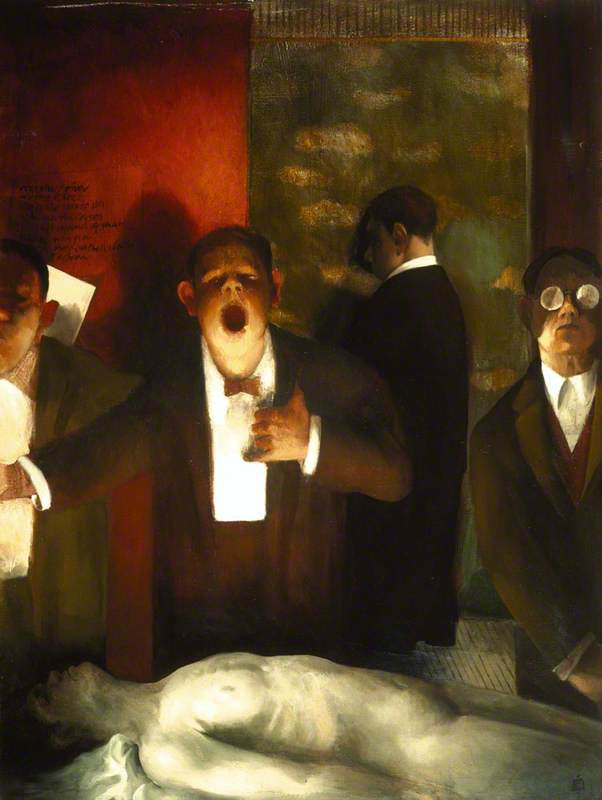

Something important happened around the time Gilman was making this painting: he met Walter Sickert and his style began to change. Until then he was most influenced by James McNeill Whistler, with his subdued palette and smooth surfaces. Under the influence of Sickert, as well as fellow Camden Town Group artists Spencer Gore and Charles Ginner, Gilman began to move towards the brighter tones of Cézanne, Gauguin, and especially Van Gogh. You can see in paintings like Interior with Nude (1911–1912, Leeds Art Gallery) that he was experimenting much more with colour and with Van Gogh-like daubed brushstrokes.

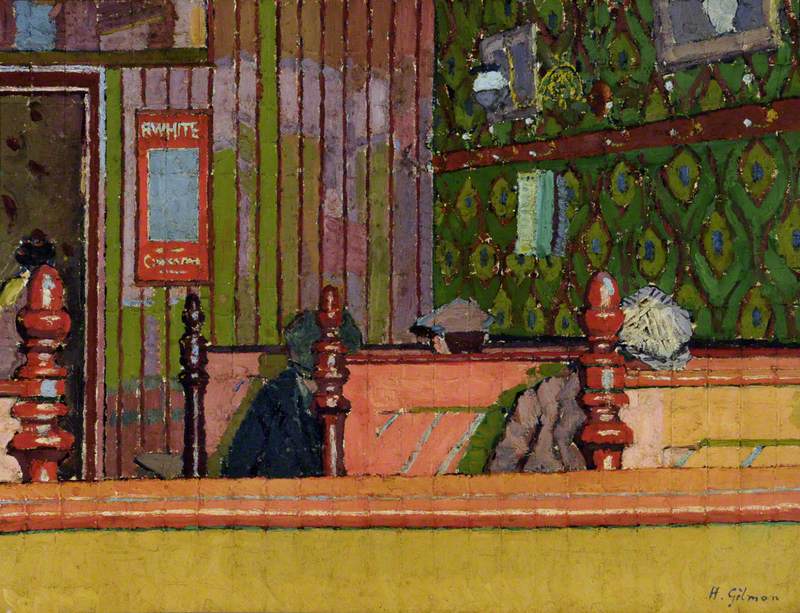

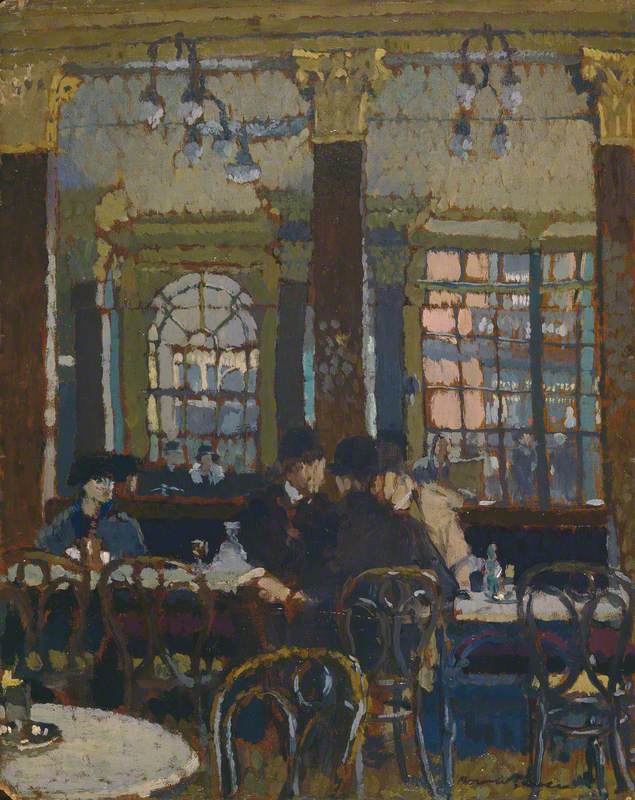

The Camden Town Group focused on everyday life and interiors, exemplified by Eating House (1914, Museums Sheffield), with its greens, browns and yellows both drab yet bright.

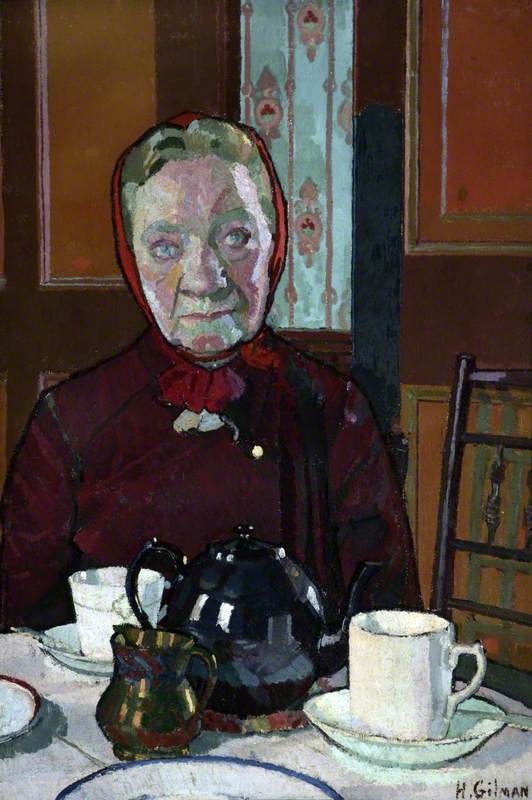

A year or two later Gilman began regularly painting Mrs Mounter, perhaps one of the most famous landladies in art. Of the many versions of this frank older woman, I prefer the portrait at the Walker Art Gallery (1916), with her world-weary stare, the red scarf tightly framing her face, and the dark teapot gleaming on the table in front of her. This is Gilman at his most confident.

The Artist's Daughters is poised between Gilman's early and later styles, and I can see in it hints of where he would end up. Compare the painting with his flat, sober portrait of his wife, Grace Canedy (1904, Aberdeen Art Gallery), and you'll notice that three years later, Gilman's brushwork when rendering his daughters is much looser, as in that glorious swoosh of yellowy-white paint to indicate the sunlit arm of the chair, for instance. The white dots around the younger girl's eyes like something you would see in a Van Gogh, and they work.

Grace Canedy

(the artist's first wife) c.1904

Harold Gilman (1876–1919)

What strikes me about this painting is its transitory feel. Gilman is moving between styles, just as the girls are about to change their lives, moving from England to the United States and a life without their father. None of them exactly knew this while the painting was being made, but the calm before the storm is palpable.

Tracy Chevalier, author