Readers who know their Greek mythology may recognise the damsel in distress shown in this oil painting by the Venetian Renaissance artist Titian. It is Andromeda, the beautiful princess of classical legend, who was offered up in human sacrifice to appease the gods made angry by her mother's vanity.

Her plight has already triggered the epic battle between the hero Perseus and the ferocious sea monster sent to devour her. Their fight rages over the water, while the immobilised princess's vulnerable body cuts across the composition, a poignant reminder of the fragile human life at stake. Love wins out: Perseus rescues Andromeda and carries her off to Greece to reign as his queen.

But should we really associate the figure of Andromeda with the pale body Titian gave her? After all, she was the daughter of Ethiopian rulers. In his Heroides, the Roman mythographer Ovid specifically evoked the 'dark Andromeda', a description more in line with her parentage.

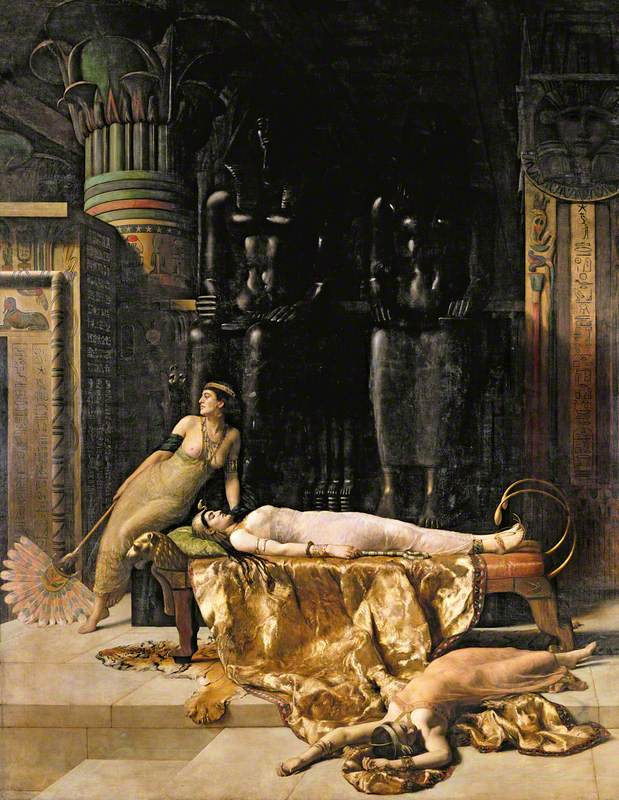

As scholars such as Elizabeth McGrath have shown, the phenomenon of 'whitewashing' – making black female figures white – is all too common throughout the history of western art and literature. Heroines such as the Queen of Sheba, Cleopatra, and, of course, Andromeda have been fundamentally altered, their cultural ties and lineage denied in an effort to adhere to standards conflating whiteness and beauty.

In the Old Testament, the Queen of Sheba, in the original Hebrew, declares proudly: 'I am black and beautiful.' But by the fourth-century Latin Vulgate translation of the bible, her statement had been diminished to: 'I am black but beautiful.'

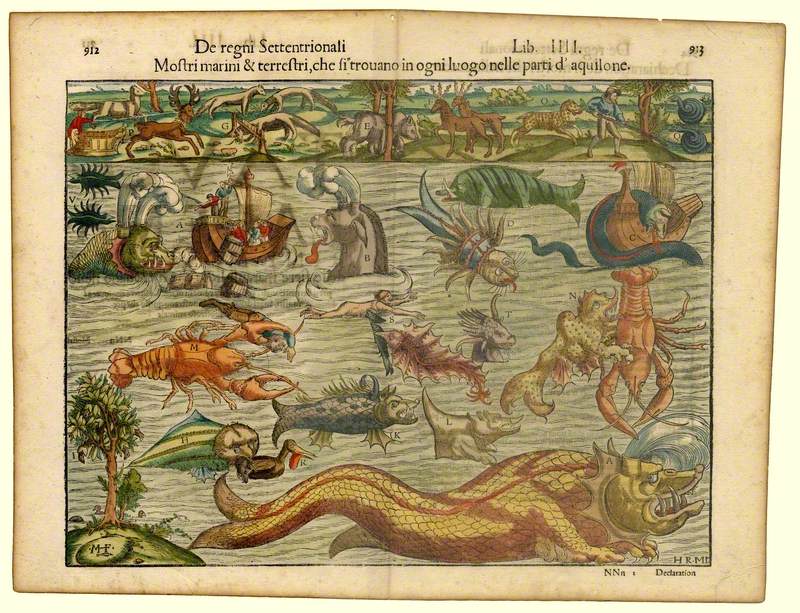

If this same erasure of identity is visible in François Lemoyne's Perseus and Andromeda of 1723, also at the Wallace Collection, viewers may at least meet the true 'dark Andromeda' of Ovidian lore in Bernard Picart's etching of 1731, housed at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. With her skin colour in contrast to the whiteness of the rock and the gulls around her, this Andromeda is clearly a black woman. With her flowing hair and sensuous pose, she is also unmistakably the beautiful princess of legend.

Bernard Picart (printmaker), after Van Diepenbeeck

— medievalpoc (@medievalpoc) June 3, 2016

Perseus and Andromeda

Netherlands (1731), after original (1655) pic.twitter.com/v2BE56Izyt

Dr Yuriko Jackall, Head of Curatorial & Curator of French Paintings, The Wallace Collection