For some very peculiar reason, the Scottish artist Dame Elizabeth Violet Blackadder (1931–2021) is not a household name, although she is widely respected and appreciated for her lyrical watercolours, prints and oil paintings. She was remarkably the first woman to be made a member of both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy.

Her delicate and exquisite flower paintings came to prominence in the 1960s, though fewer people realise how truly versatile her practice is. Now in her eighties, Blackadder arguably deserves the same acclaim as any other great British modernist painter. To celebrate her life and work, here is a selection of some of her finest creations on Art UK.

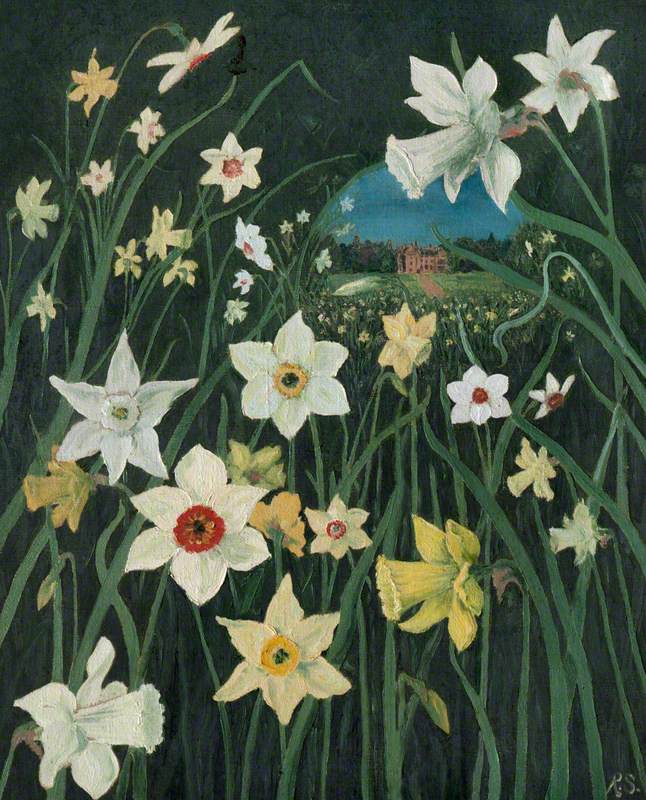

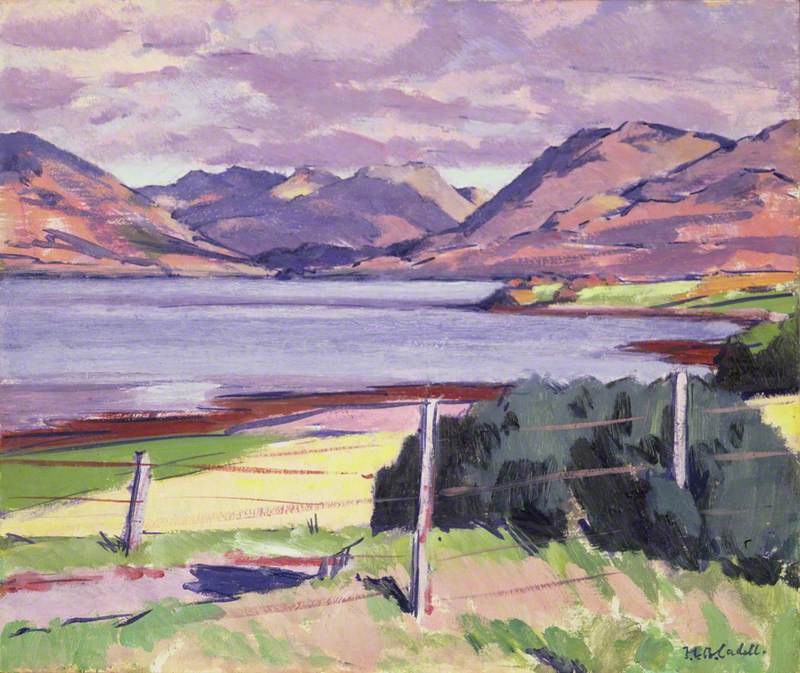

Blackadder was born in Falkirk, Scotland in 1931. The daughter of parents who encouraged her learning and education, she apparently spent a large part of her childhood alone, during which time she would collect plants and flowers, meticulously labelling them with Latin names to create a botanical typology. This interest in nature would reappear consistently in her much-loved work, and she has been an avid gardener for most of her life.

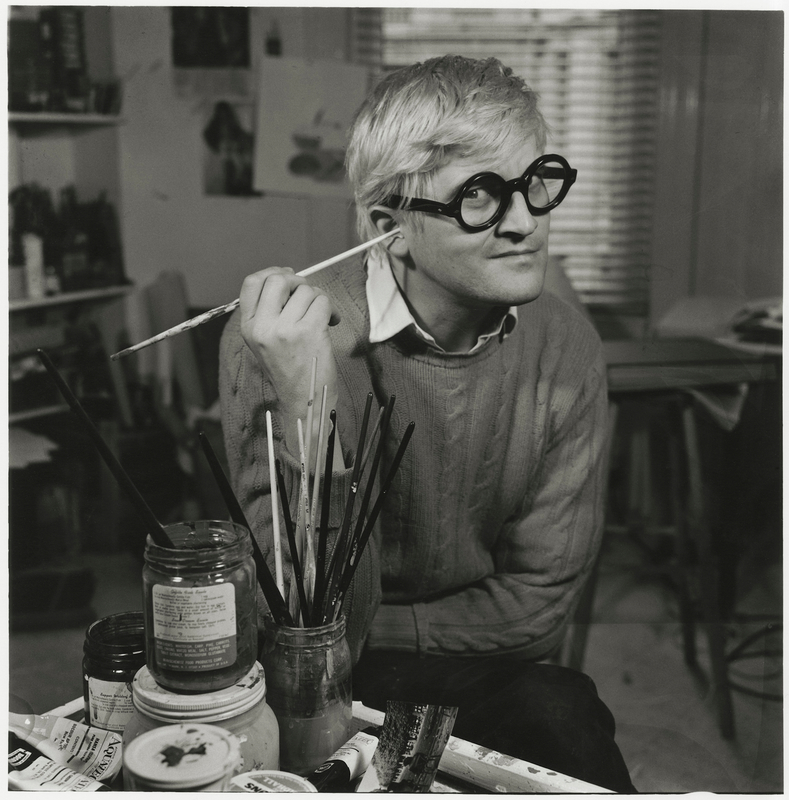

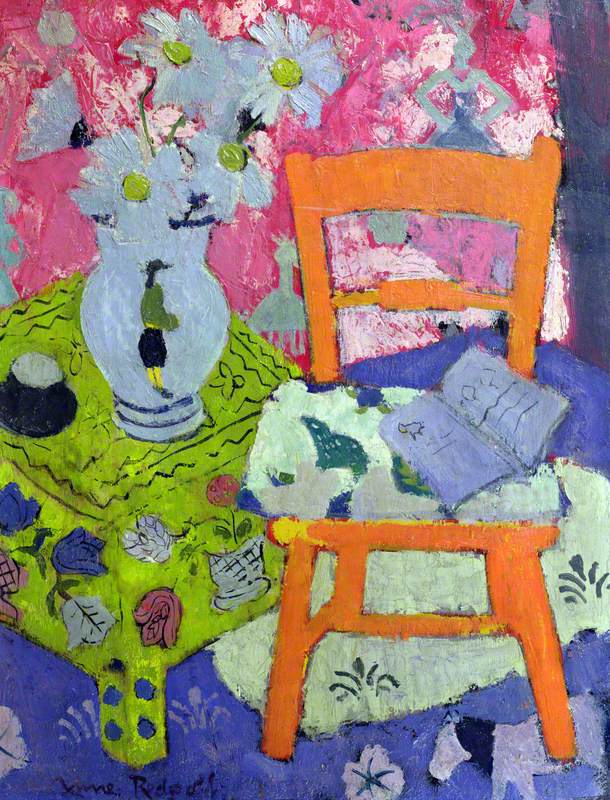

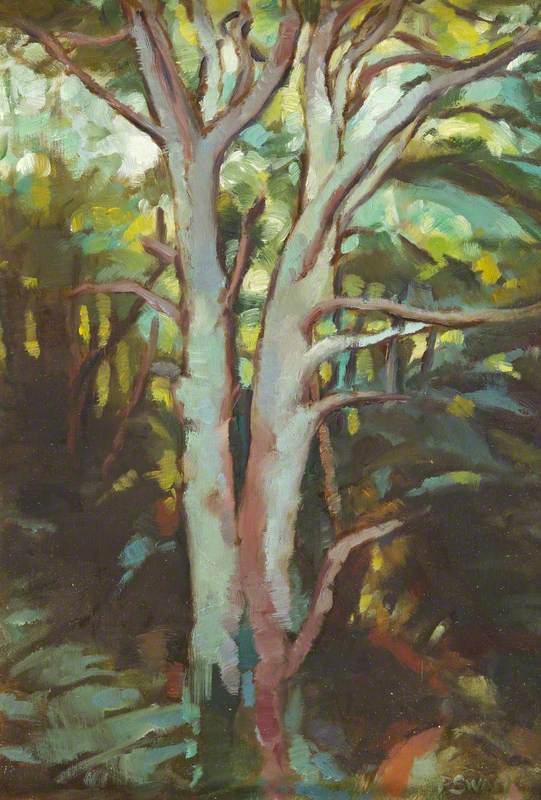

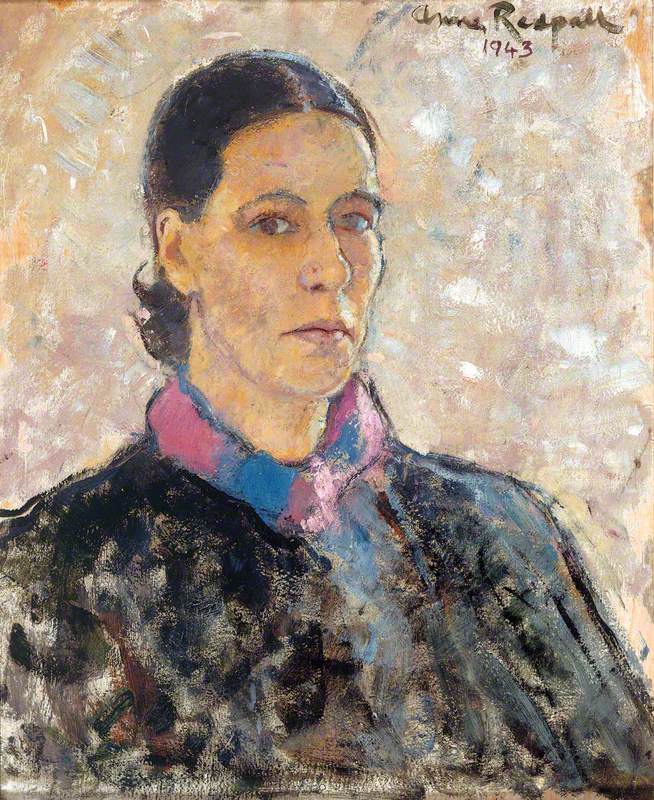

Studying at both Edinburgh University and Edinburgh College of Art, she was taught by some of Scotland's most notable painters of the time like William Gillies, who had a particular impact on her work. Whilst in Edinburgh she also mixed with other notable female artists like Anne Redpath, and also met the artist John Houston (1930–2008), who would later become her husband in 1956.

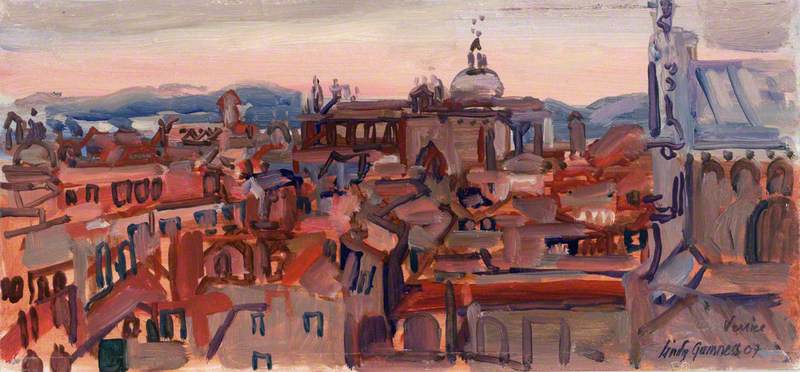

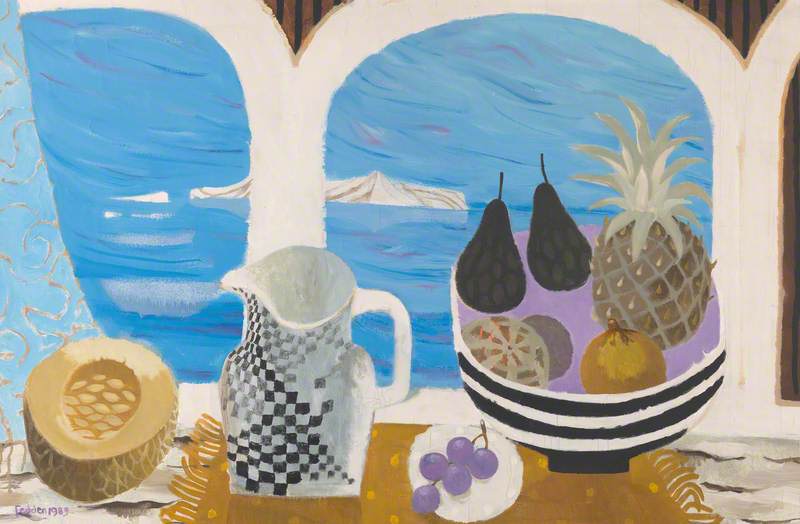

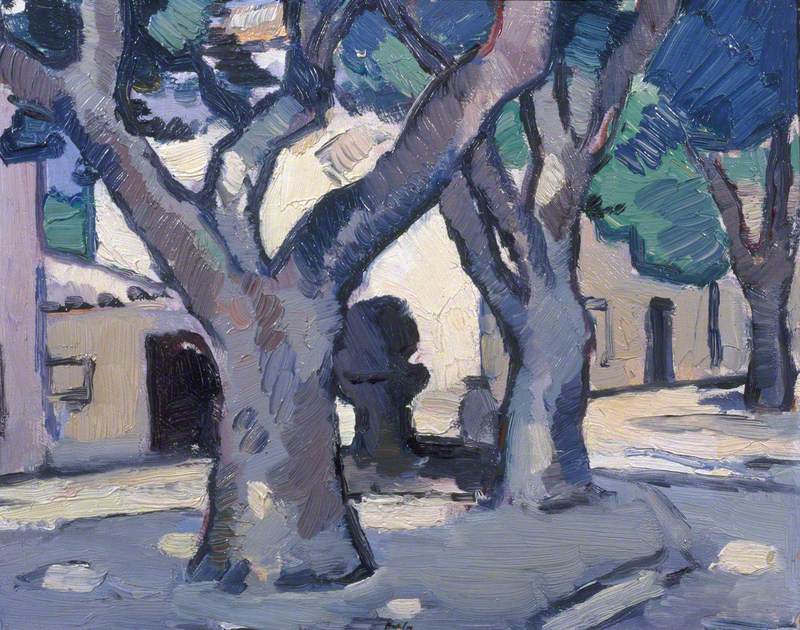

She received travel scholarships after graduating, allowing her to travel around Europe.

In France, she became acquainted with the colourful fauvist paintings of Henri Matisse, and while in Italy she observed the modernist and sombre paintings of Giorgio Morandi. She also travelled to Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia.

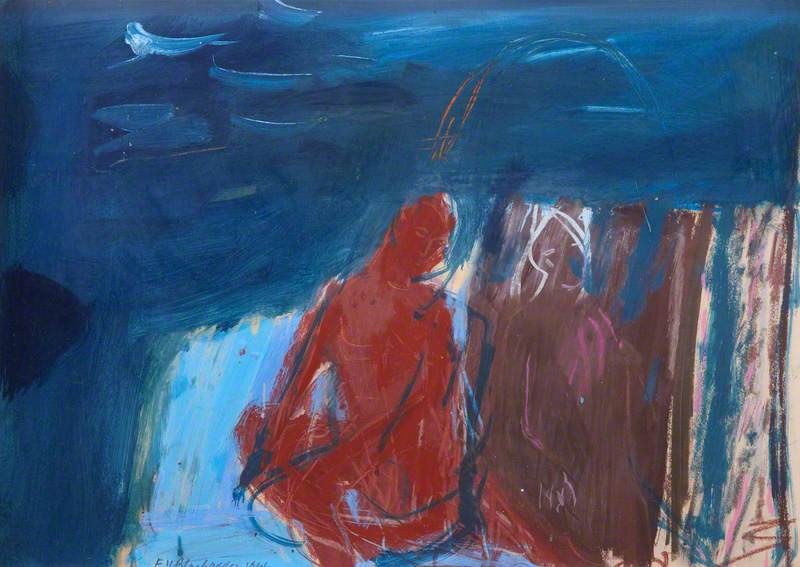

In her early career, she appears to have been experimenting with different forms of subject matter, ranging from still lifes to nude portraits to landscapes and abstract compositions.

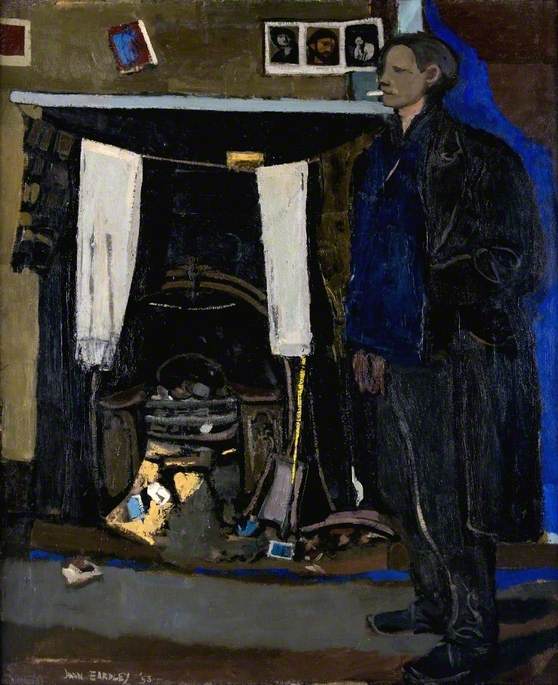

Reclining Male Nude

(verso) 1953

Elizabeth V. Blackadder (1931–2021)

Around this time, she was increasingly turning towards the American post-war Abstract Expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

Her first solo exhibition was in 1959 at 57 Gallery in Edinburgh.

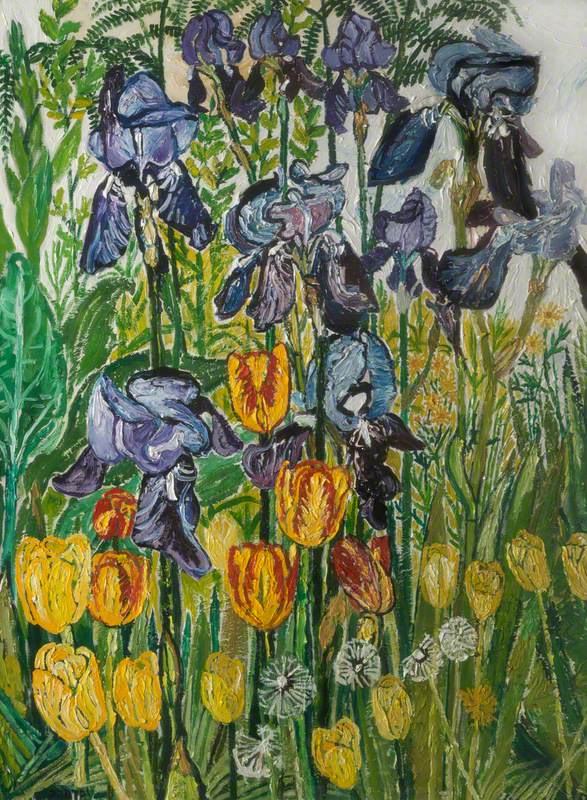

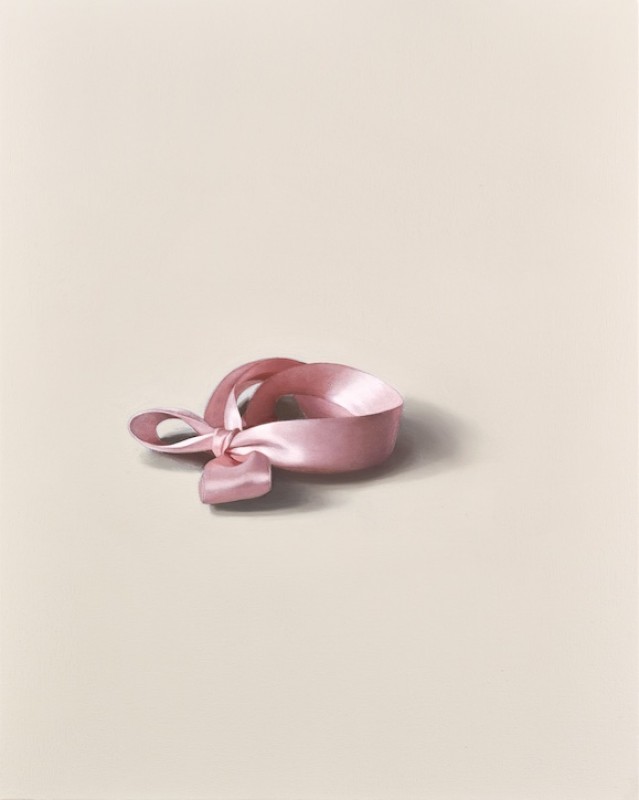

By the 1960s, Blackadder had gained a reputation for her elegant flower colour lithographs and watercolours, setting her apart from her contemporaries. According to writer Deborah Kellaway, Blackadder's favourite flowers have always been irises, poppies, tulips, lilies and orchids, though she has frequently also painted hellebores and anemones.

Blackadder would remain in Edinburgh lecturing at the Edinburgh College of Art from 1962 until her retirement in 1986.

The Scottish art historian Duncan Macmillan once remarked that Blackadder's floral paintings are 'based on a description that is so fastidious it becomes poetic', a habit most likely originating from her childhood obsession with collating and classifying different forms of flora. Her artistic approach is virtually scientific – precise, analytical and objective – although the overall outcome is lyrical, soft and clearly imbued with the artist's subjective love for flowers.

The simple white background allows the viewer to focus on the harmonious colours while paying close attention to the exquisite detail. Such a composition perhaps pays homage to the many historical forms of botanical studies of flora and fauna.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1700–1758) was another Scottish artist and author who created extensive research into flora in the eighteenth century, which ultimately became an invaluable resource for physicians and apothecaries. Her studies and illustrations of herbs and exotic plants from the 'New World' formed the critically-acclaimed book A Curious Herbal (written with her husband Alexander Blackwell). Today, her intricate illustrations can be viewed at the British Library and the Wellcome Collection.

In the twentieth century, botanical artist Lilian Snelling (1879–1972) was widely praised for her beautiful illustrations of plants and flowers that featured in Curtis's Botanical Magazine and illustrated books for Kew Gardens.

In 1972, Blackadder became a member of the Royal Scottish Academy and in 1976 a member of the Royal Academy of Art, making her the first woman to be elected into both, a prestigious badge of honour that further legitimised her artistic significance and influence.

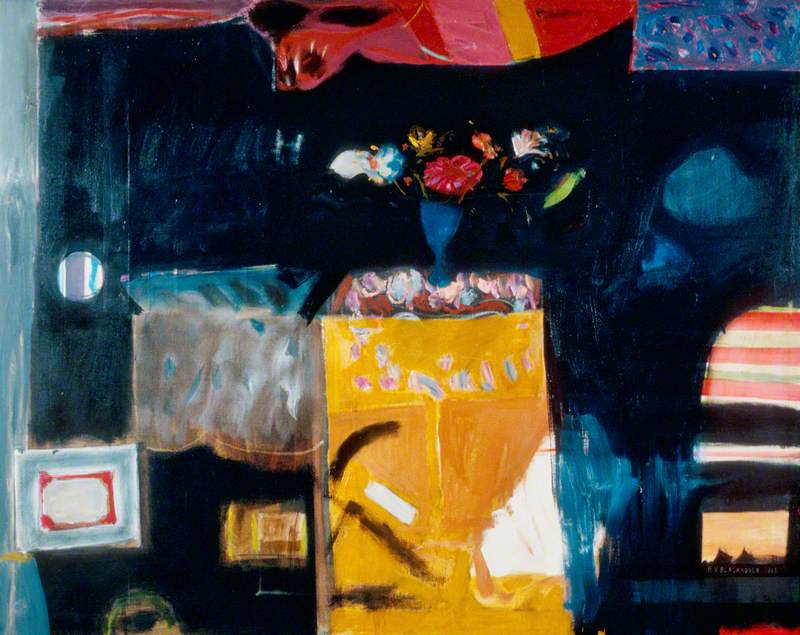

By the 1970s, Blackadder’s subject matters had become increasingly inspired by her many travels abroad, in Europe and Asia.

In Tulips and Indian Painting completed in 1977, the viewer looks into a room in which a mirror hangs on a wall. The mirror's reflection reveals a Mughal miniature painting, accentuated by the bright orange and blue colours of the cloth resting on the chair. The work is not dissimilar to one of Blackadder's most famous paintings Flowers on an Indian Cloth (1965), particularly for the repeated decorative patterns on the walls.

In the 1980s, Blackadder's work became increasingly inspired by Japan's art and cultural traditions, an interest which, according to the artist, was first ignited after seeing an exhibition about Japanese art in London. She travelled to Japan regularly, a country which she seems to have been fascinated by. Her studio is filled with objects and clothing from Japan, including kimonos, fans and figurines.

Around this time, Blackadder also started to use Japanese paper for her watercolours, imitating the rich cultural tradition of watercolour painting in Japan.

Four Flowering Plants, One Possibly a Toad Lily (Tricyrtis Species)

c.1870

unknown artist

In 1982 Blackadder was appointed an Order of the British Empire.

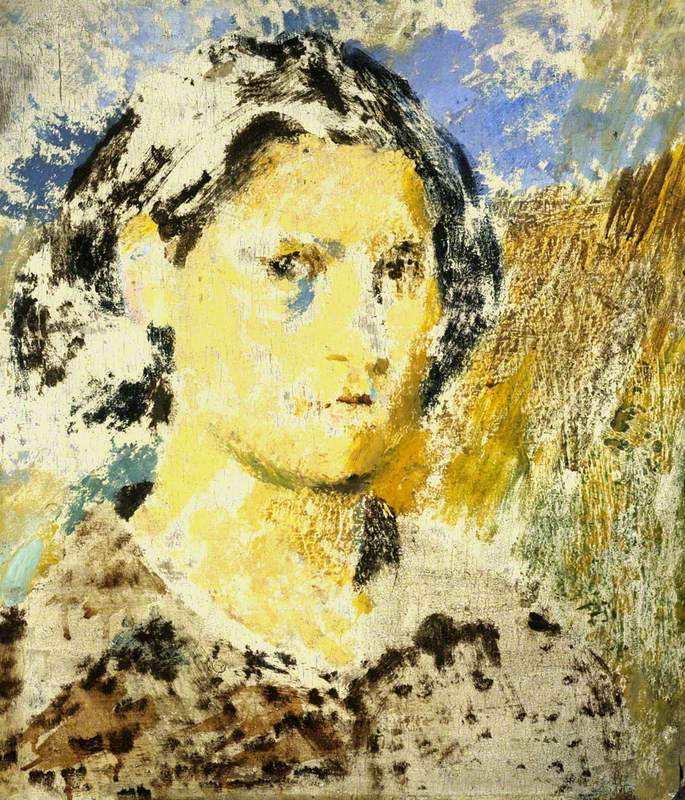

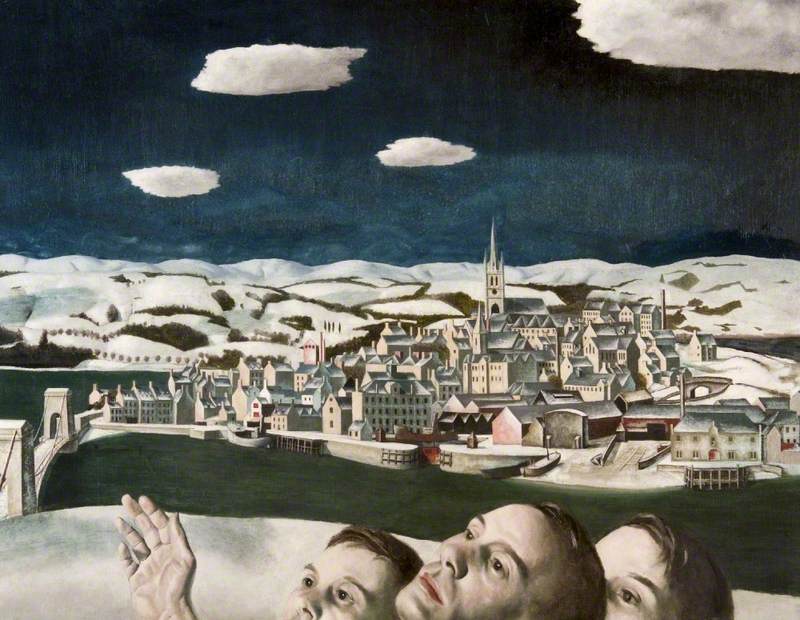

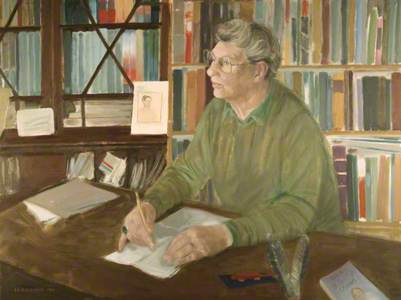

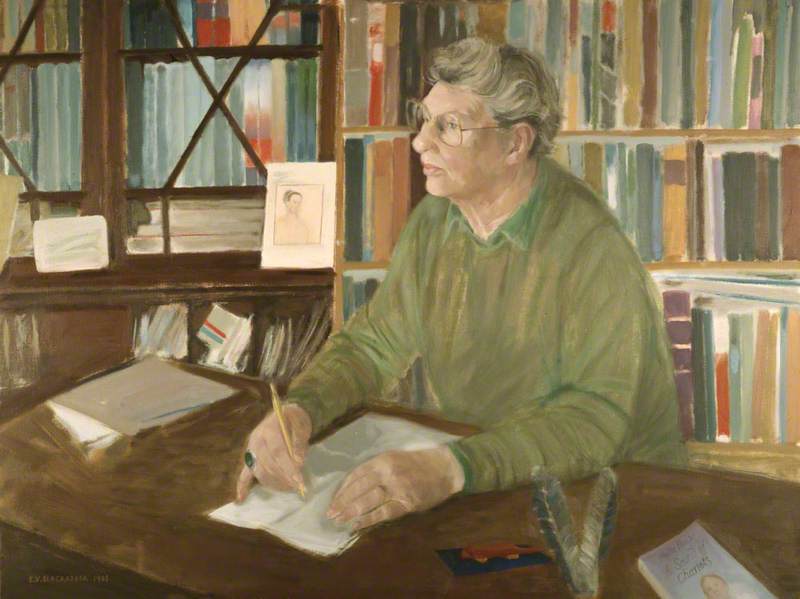

In 1988, Blackadder completed this oil on canvas portrait of Scottish fantasy writer Mollie Hunter, which is housed in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

In 2001, she was made the first female Artist Limner by the Queen, a position within the Royal Household unique to Scotland. One decade later, in 2011 (the same year she turned 80) a major retrospective of her work opened at the Scottish National Gallery, curated by Philip Long.

Mollie Hunter (1922–2012), Writer

1988

Elizabeth V. Blackadder (1931–2021)

Blackadder has been a much-loved Scottish artist for over half a century. However, her talents deserve further praise, examination and critical attention.

In the artist's own words: 'I don't really talk about my art.' Instead, she always allowed her practice to speak for itself.

As much a collector as an artist, Blackadder's artistic vision was inspired and stimulated by a sheer curiosity for the world around her, which she beautifully documented and illustrated for over six decades.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK