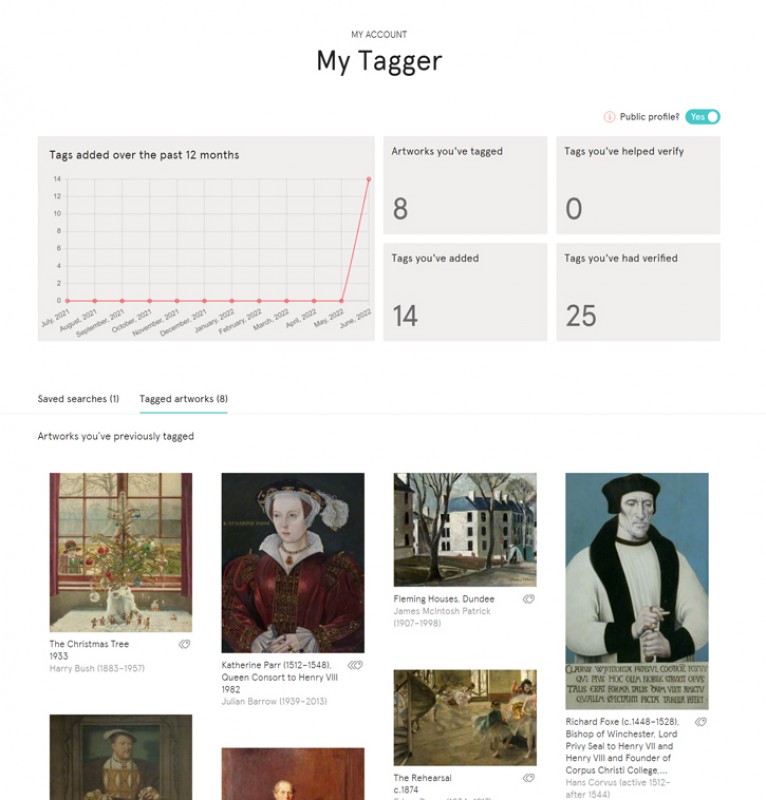

Anyone attempting to have a good look at the Melville Monument in Edinburgh has to crane their head and squint to make out the sharp and exaggerated features of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville (1742–1811), towering 152 feet above the centre of St Andrew Square.

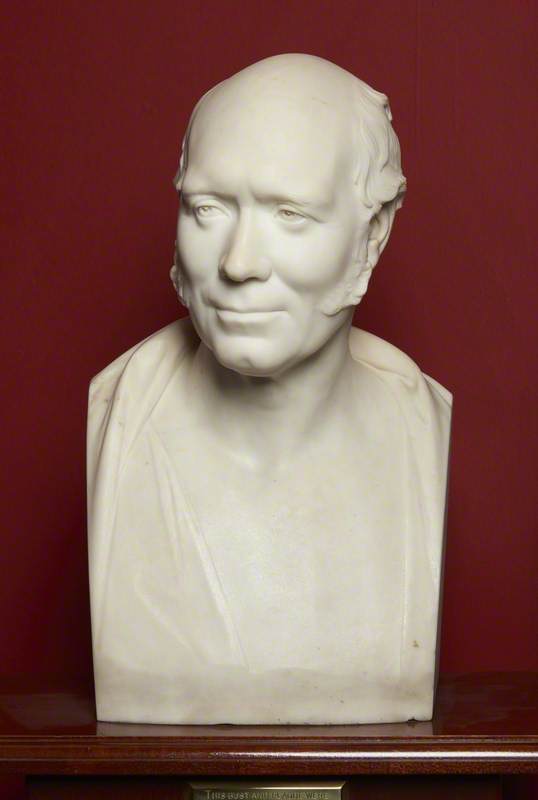

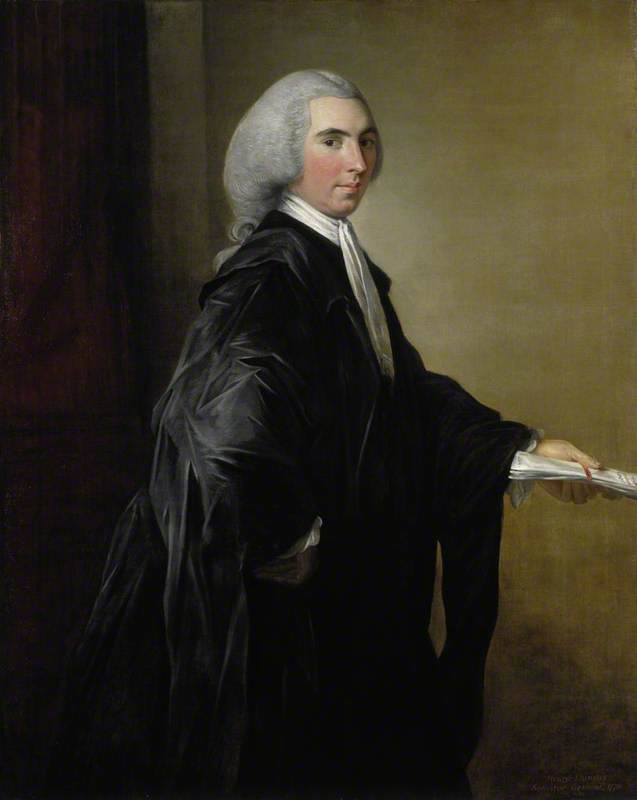

Henry Dundas (1742–1811), 1st Viscount Melville

1817–1827

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841) and Robert Forrest (1791–1852) and William Burn (1789–1870) and William Armstrong (active 1817–1827)

Dundas – the most powerful Scot in the British Government at the end of the eighteenth century – was a man known by many names, including the Uncrowned King of Scotland.

He was the Lord Advocate, an MP for Edinburgh and Midlothian, and the First Lord of the Admiralty. In 1802, he was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Melville and Baron Dunira.

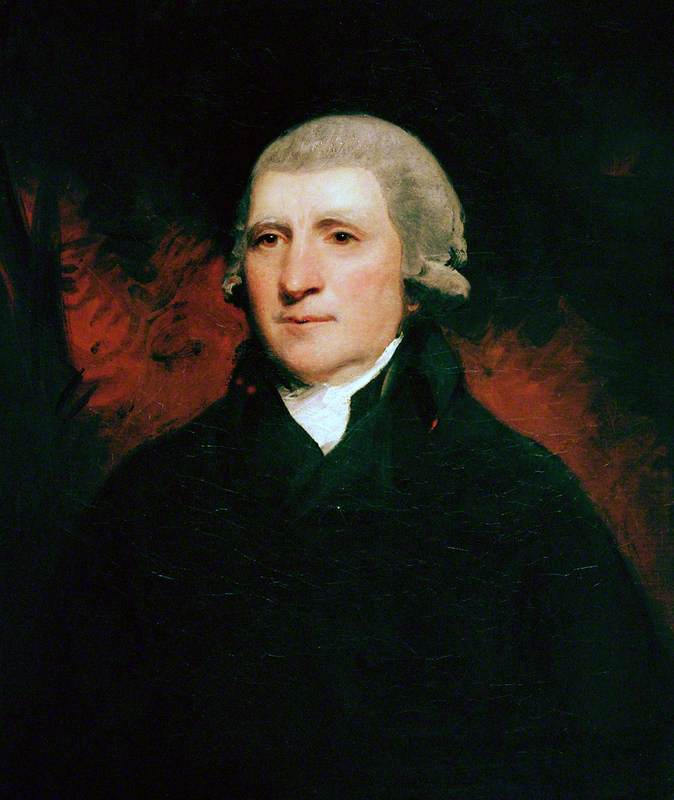

Henry Dundas (1742–1811), 1st Viscount Melville

John Hoppner (1758–1810)

His actions – and the monument to him – have been the subject of well-publicised recent scrutiny and debate. His looming presence in the heart of Edinburgh's Georgian New Town is certainly controversial now, but what is less well known is that this enormous statue was contested even before it was built two centuries ago.

Unusually, the statue began life not as a public monument but paid for by private subscription from family, friends and members of the Royal Navy. With one marble statue by Francis Leggatt Chantrey already taking up significant space in Parliament House in the city, even The Scotsman newspaper at the time deemed a second one superfluous.

Though highly unpopular with the general public, the enduring political influence of the Dundas family helped to push through the project despite years of disputes over locations and finances, and the column was erected in 1821. The Scotsman noted at the time that sailors were threatened with exemption from promotion if they didn't contribute to the cost of the project.

Henry Dundas (1742–1811), 1st Viscount Melville

1817–1827

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841) and Robert Forrest (1791–1852) and William Burn (1789–1870) and William Armstrong (active 1817–1827)

The 15-foot statue, based on a design by Chantrey, was carved by the Scottish sculptor Robert Forrest out of Cullalo sandstone from a quarry in Fife. Coincidentally, this was the same stone used to build the 'handsome gaol' in Port of Spain, Trinidad, that was referred to by Mrs Alison Carmichael, a Scottish writer, in her diaries of her travels around the West Indies. She boasted of the quarry near Aberdour that was owned by her father.

The statue of Dundas was finally placed on top of the fluted Roman column created by William Burn in 1827, a decade after supporters had started raising funds, and 16 years after Dundas's death.

The residents of the square were so alarmed at the possibility of this large and heavy monument falling on one of their homes, that the lighthouse engineer Robert Stevenson was brought in to advise on safety issues.

Just a decade later, in 1837, the monument was badly damaged by a lightning strike. That same year, British former enslavers were compensated to the tune of £20 million after slavery was abolished, while formerly enslaved African people across the British Caribbean were still being forced to work unpaid under a new apprenticeship system.

But just who was the man behind the statue? Dundas began his career as a lawyer – in a landmark case he successfully defended Joseph Knight, a formerly enslaved African man brought from Jamaica, from an attempt by the former enslaver John Wedderburn to keep him in perpetual servitude in Scotland.

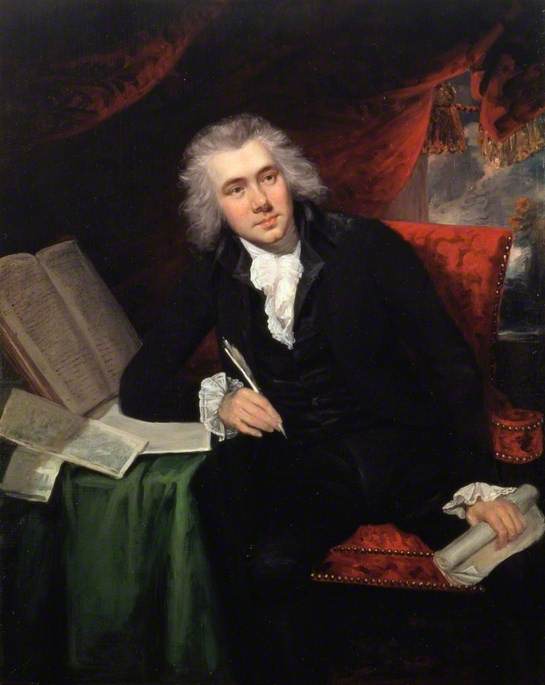

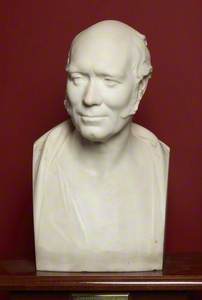

Henry Dundas (1742–1811), 1st Viscount Melville, Statesman

1770

David Martin (1737–1797)

Close friends with William Pitt the Younger, the Tory Prime Minister whose Edinburgh statue stands not far from St Andrew Square, Dundas went on to enjoy an astonishing array of top positions in the Government, as well as powerful influence over Scottish MPs in what was described at the time as his system of 'pillage and patronage'.

William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806)

1831–1833

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841)

In June 1792, during a time of food shortages, Edinburgh was the scene of the 'Dundas riots'. Anger towards a repressive Government shocked the elites as crowds pelted dead cats and other missiles at the army, smashed homes belonging to members of the Dundas family, and burned life-sized effigies of Henry Dundas himself.

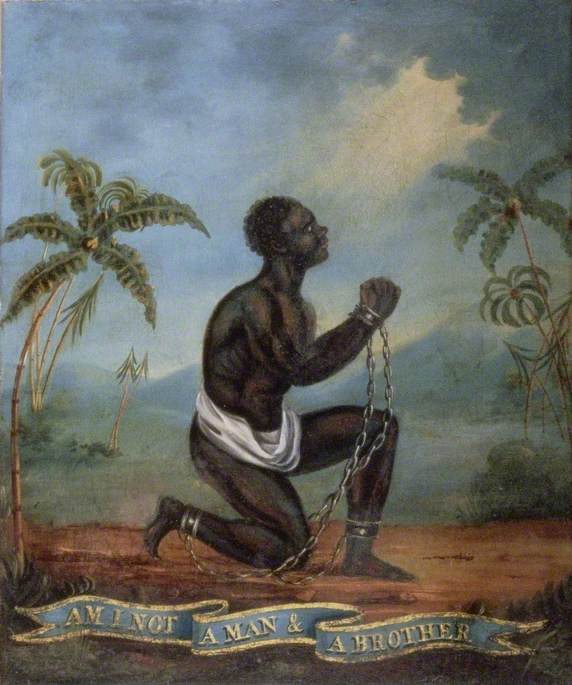

That year, while Dundas was Home Secretary, there were petitions from disenfranchised people flooding the British Parliament demanding the immediate abolition of the slave trade, supporting William Wilberforce's motion on the matter.

The Edinburgh petition was presented by Dundas himself, who notoriously succeeded in inserting the word 'gradually' into the motion, to the great relief of those financially invested in the slave trade. Slave trading by British ships was not abolished until 1807, and, as a result of this delay, more than half a million African people were kidnapped and trafficked across the Atlantic.

Part of Dundas's plan, one that was also regularly mooted by abolitionists, was to traffic African girls and boys under 16 and 20 respectively into a system of forced reproduction in the Caribbean, where barbaric labour conditions and regular torture meant that it was not uncommon for enslaved people to die three to five years after arriving on a plantation.

Dundas and Pitt worked closely together to enact repressive laws at home, oversee vicious reprisals against resistance by the enslaved, and attempt to expand the system of chattel slavery.

When the opportunity arose once more in 1796 to support the immediate abolition of the slave trade, Dundas opposed it again. Britain was in the thick of war with France, and Pitt and Dundas, who was now Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, had committed themselves to a costly and unpopular conflict fighting for the lucrative sugar islands of the West Indies.

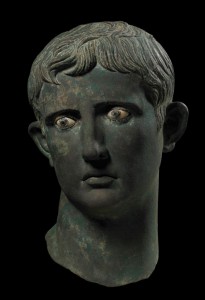

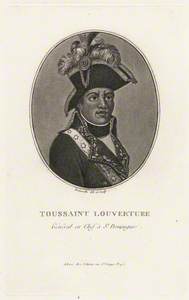

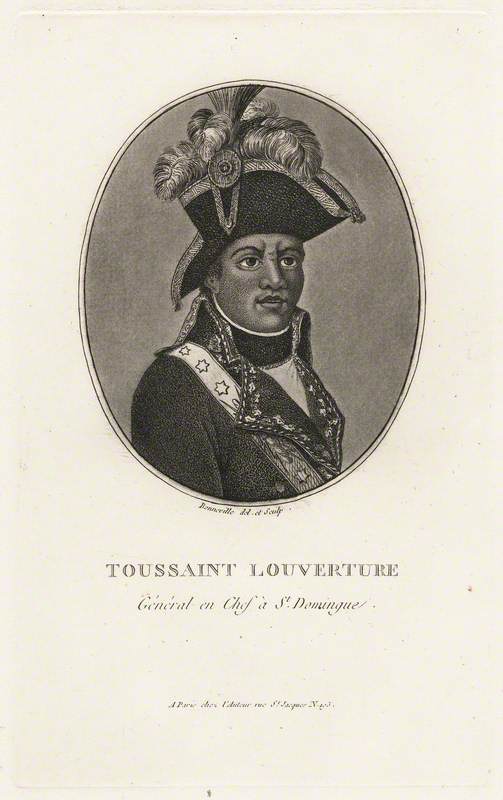

Toussaint L'Ouverture

(after an earlier work by an unknown artist) early 19th C

François Bonneville (active 1787–1802)

The British Government orchestrated the slaughter of resistance leaders to reinforce the slave system in islands such as Jamaica and Grenada, and oversaw the genocide and exile of the indigenous people of St Vincent.

Not content with bolstering their own slave colonies, the British made an ill-judged and desperate attempt to take over Saint-Domingue and reinstate chattel slavery after the successful revolution by the formerly enslaved, led by Toussaint L'Ouverture, which led to the free Black republic of Haiti, with its own advanced constitution of equality for all.

With stories pouring in about the deaths of thousands of British men, and hopeless military failures in Haiti, rebellion against conscription was growing, and a series of mutinies by sailors who had been press-ganged into service was causing alarm for Dundas. He began to use enslaved African people to fill the depleted West India regiments, and enacted a series of Bills to protect white British sailors' families from destitution.

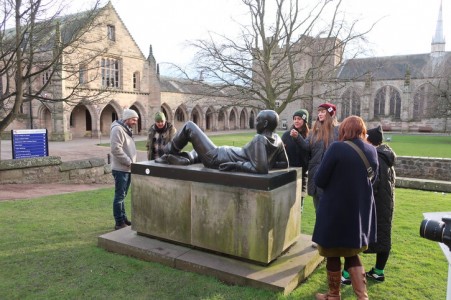

Until recently, most Edinburgh residents probably hadn't given a moment's thought to the life of Henry Dundas, the person memorialised so grandly at the centre of their city. St Andrew Square became open to the public only in 2008, when an inconspicuous plaque was placed several feet away from the foot of the refurbished statue.

NEW: @SirGeoffPalmer renews call to reword history on an #Edinburgh statue memorialising man who prolonged the slave trade https://t.co/gro3EAEOHs

— Edinburgh Evening News (@edinburghpaper) June 6, 2020

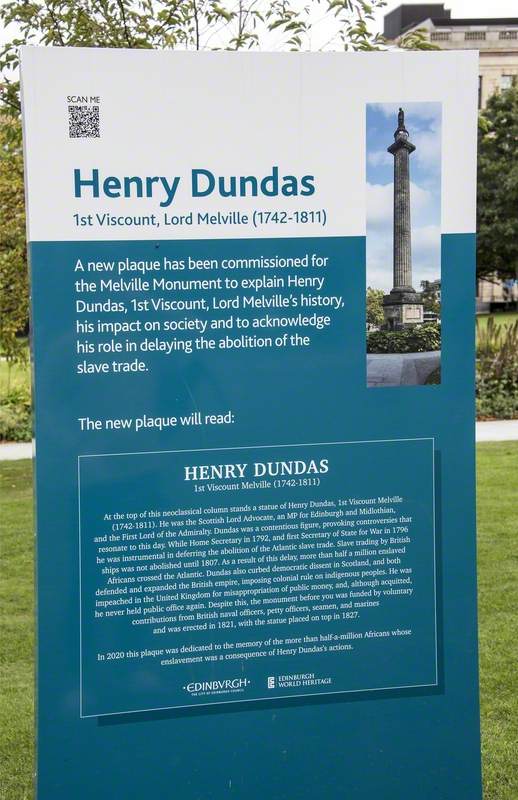

For several years, Sir Geoff Palmer, the Jamaican academic, human rights activist and now Chancellor of Heriot-Watt University, campaigned with Adam Ramsay, an activist in Edinburgh, for a new plaque mentioning Dundas's role in Caribbean slavery.

However, the argument ended in a state of deadlock when faced with two equally determined opponents – Bobby Melville, a descendant of Dundas, and Michael Fry, a historian and biographer of Dundas.

Henry Dundas (1742–1811), 1st Viscount Melville

1817–1827

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841) and Robert Forrest (1791–1852) and William Burn (1789–1870) and William Armstrong (active 1817–1827)

It took the spotlight of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 to force the City of Edinburgh Council to respond with pledged support for a new plaque. A temporary sign, shown above, has been placed by the statue with the agreed wording until the permanent A3 brass plaque is ready to install on the monument.

The BBC documentary Scotland, Slavery and Statues gives a good overview of the debates still swirling around the Melville Monument, with many younger people in the city wanting Dundas gone entirely.

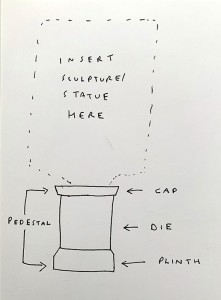

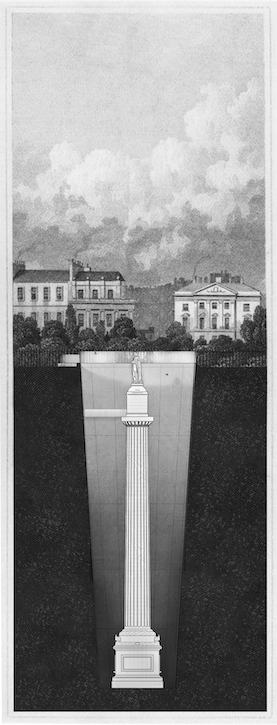

Architect Tom Fairley's reimagining of the monument as sunken into the ground won him the top prize in The John Byrne Award for 2021, and architectural students at the University of Edinburgh recently reimagined St Andrew Square with the Melville Monument completely absent.

Is Our Past Set in Stone?

2021, digital design by Tom Fairley

For now, Henry Dundas remains smugly secure on his giant pedestal, untouchable by those who might want him rolled down one of the hills in the New Town towards the sea, and sunk into the seabed like so many of the people who didn't survive the Middle Passage.

While his imperious stone tribute remains, let's consider if we want to maintain a symbol of the terror inflicted by certain Scots at home and across the globe in the name of upholding the newly entrenched class system and the white supremacy of the British Empire.

However, it's important to remember that all of this can potentially act as a costly distraction from dealing with the actual legacies of the slave trade – the racism, poverty and neo-colonialism that have resulted from decisions made during that period.

Lisa Williams, author and founder of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association

This content was supported by Creative Scotland