'My business is to paint what I see, not what I know is there' – J. M. W. Turner

In December 2018, the Turner Prize was awarded to the Glasgow-based artist Charlotte Prodger, whose work highlights queer identity through the medium of video shot on an iPhone. In light of the announcement, Art UK looks back to seven previous winners, considering whether the ethos of the prestigious award (now in its 34th year) has changed since its inception.

First established by the Patrons of New Art in 1984, the Turner Prize was named after the great painter J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), who had an unfulfilled desire to set up a young artist’s prize. From its origins, the Turner Prize has aimed to celebrate contemporary – and sometimes controversial – artists working in the same visionary spirit as Turner. Originally intended for British nominees under the age of 50, the award has since opened its doors to all ages and diversified its selection.

But how far has it come since the 1980s? We can explore the work of previous winners through Art UK.

Let’s go back in time.

Malcolm Morley, 1984

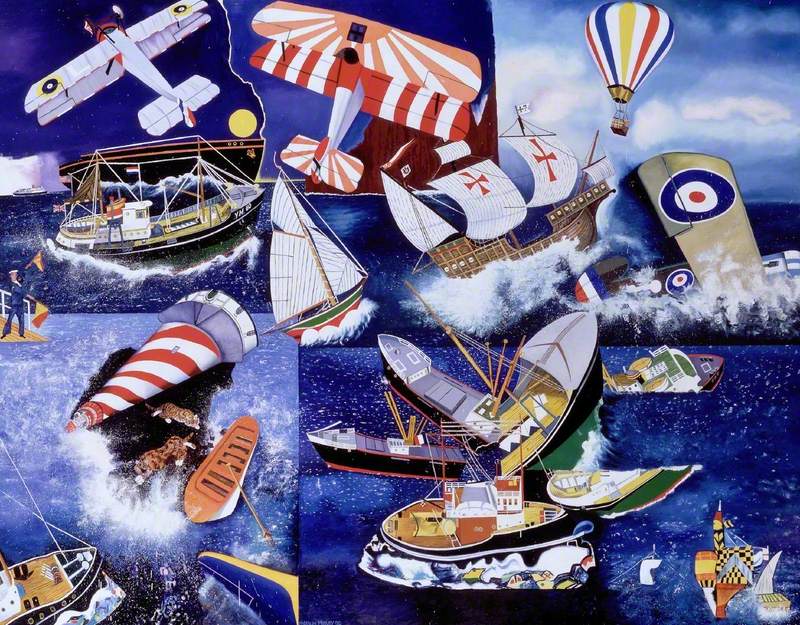

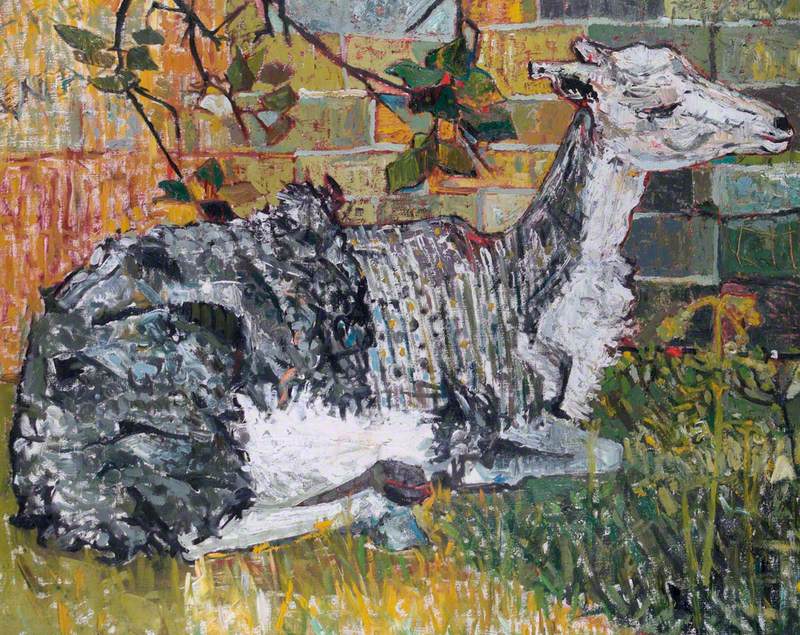

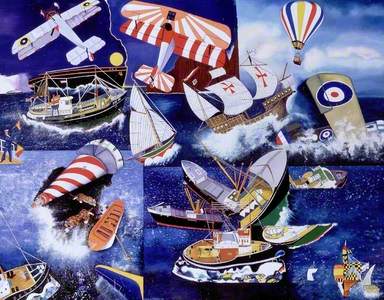

On 10th November 1984, the London-born artist Malcolm Morley, known for his Photorealist style, was announced as the first winner of the Turner Prize, exhibiting an installation of two oil-on-canvas paintings inspired by the artist’s trip to Greece.

Morley’s win sparked controversy. The artist had been living in New York for the past 20 years, and members of the British art world questioned why he should receive the £10,000 prize. Other nominees that year included Richard Long, Richard Deacon

Interestingly, Morley started painting while serving a prison sentence for burglary. He later attended the Royal College of Art, before moving to New York, where he remained until his death in June 2018. He is now, ironically, less well known than his shortlisted rivals for the prize.

Above you can see Morley’s Mariner (1998) on Art UK, another nautical-themed oil on canvas, created a few years after his Turner Prize win.

Howard Hodgkin, 1985

In 1985, painter and printmaker Howard Hodgkin was the second artist to receive the Turner Prize for his print For Bernard Jacobsen (1979). At first glance, the print appears to be abstract, though in

Hodgkin had a lifelong fascination with India and its art – in particular, sixteenth-century Mughal and Rajput miniatures, which he collected avidly. First visiting India in 1964, at the age of 32, the artist returned to the country each year, visiting the studios of modern Indian artists such as Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003) and Jamini Roy (1887–1972), who inspired Hodgkin’s use of

Damien Hirst, 1995

Jumping ahead in time, provocateur Damien Hirst won the Turner Prize in 1995 at the age of 30, receiving £20,000 for his piece Mother and Child Divided (1993), a floor-based sculpture consisting of a dissected cow and calf preserved in formaldehyde.

Part of the ‘Young British Artists’ movement – a collection of artists who graduated from Goldsmiths in the 1980s and received the patronage of collector Charles Saatchi – Hirst had become one of the movement’s figureheads, along with Angus Fairhurst, Sarah Lucas, Gavin Turk and Gillian Wearing (who was herself to win the Turner Prize in 1997).

That year was a controversial one for Hirst. His formaldehyde work, Away From The Flock (1994), had been

Although installations such as Mother and Child Divided are not on Art UK yet, spot works such as his Monument to the Living and the Dead (2006) continued Hirst's obsession with the theme of life and death.

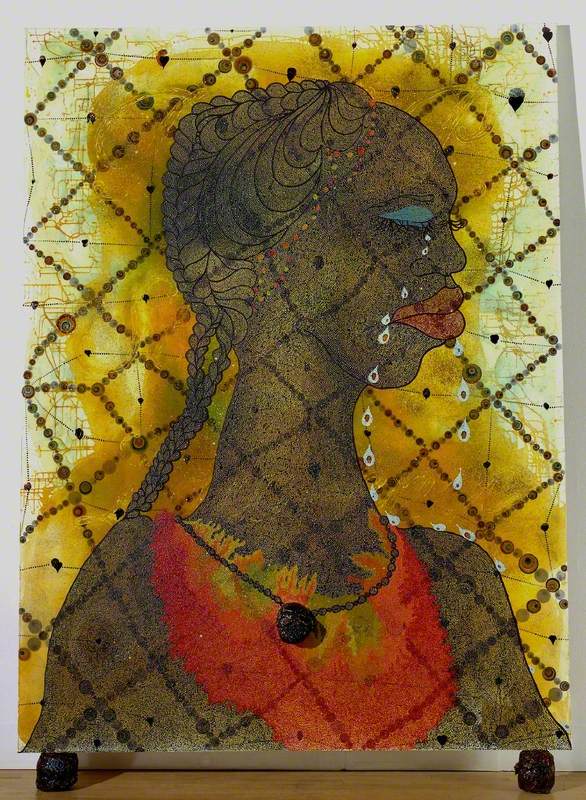

Chris Ofili, 1998

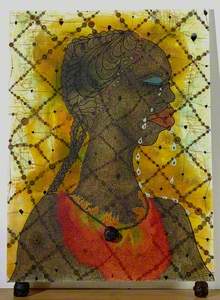

Chris Ofili was awarded the Turner Prize in 1998 for his iconic painting No Woman, No Cry (1998), surprisingly making him the first painter to receive the award since Hodgkin. But like Hirst’s controversial work, Ofili’s painting sent shockwaves through the art world.

Named after the famous Bob Marley song, the acrylic

Most importantly, the work sparked debate for its reference to Stephen Lawrence, a young boy who had been murdered in a racially motivated attack in 1993. The highly

Keith Tyson, 2002

In 2002, Keith Tyson beat other nominees Fiona Banner, Liam Gillick

The year 2002 was possibly the most controversial for the Turner Prize. The award received critical backlash, not just from art critics, but from politicians, even members of the Royal Family. Culture Minister Kim Howells described the award as ‘cold, mechanical, conceptual bullsh*t.’ His comment quickly received praise from Prince Charles, who in turn claimed that the prize had ‘contaminated the art establishment.’ Graffiti-artist Banksy also joined in on the conversation, creating his work Mind the Crap, which he

Despite the increasing uproar around that year’s selection, Tyson was praised by the judging panel for his work’s ‘strong visual energy’ across a diverse range of media that included drawing, painting, sculpture

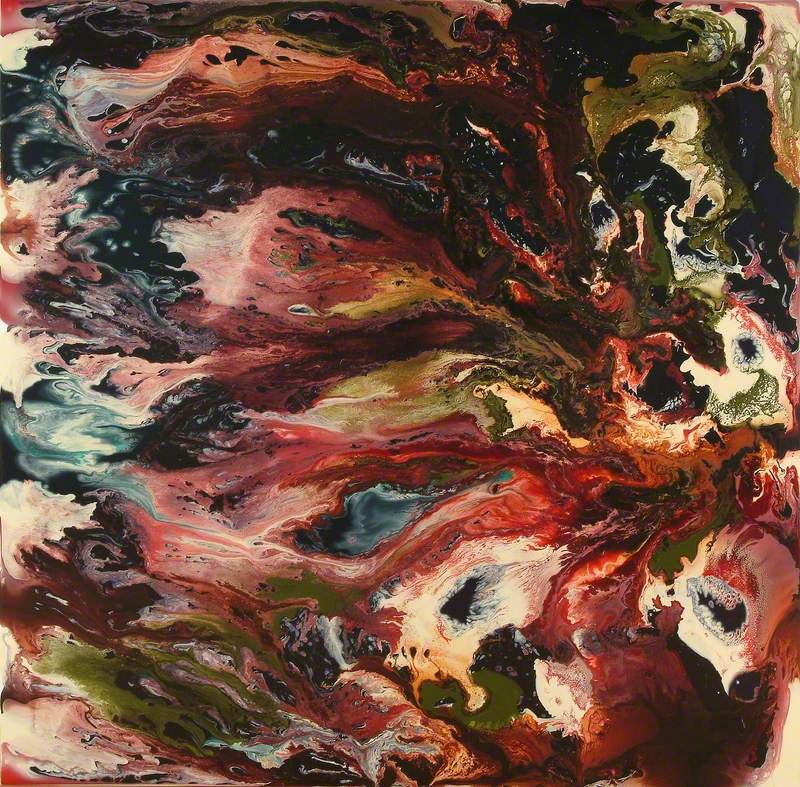

Tomma Abts, 2006

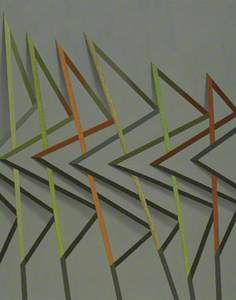

In 2006, the German-born abstract painter Tomma Abts won the Turner Prize, beating nominees Phil Collins, Mark Titchner and Rebecca Warren. Notably, she was awarded the £25,000 prize by the legendary Yoko Ono, whose speech proclaimed that London had overtaken New York as the

Nominated for her solo exhibition at

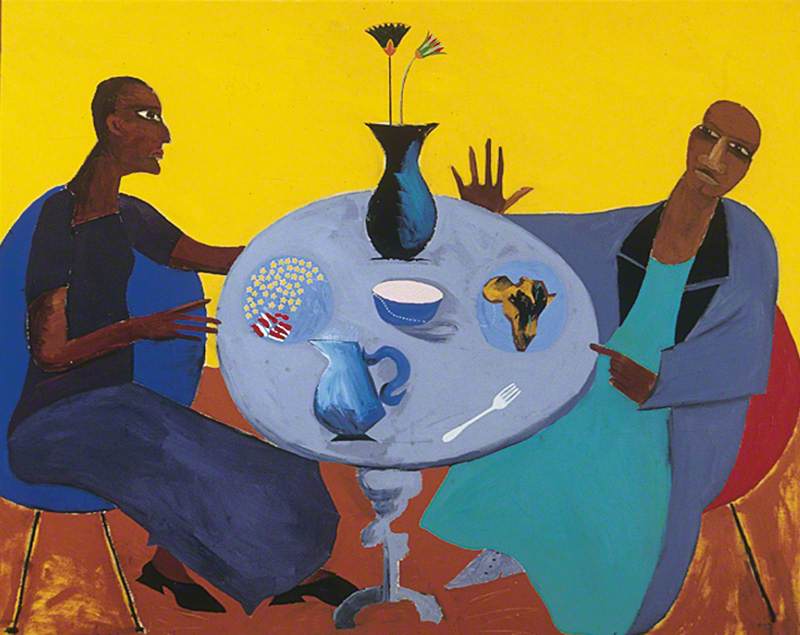

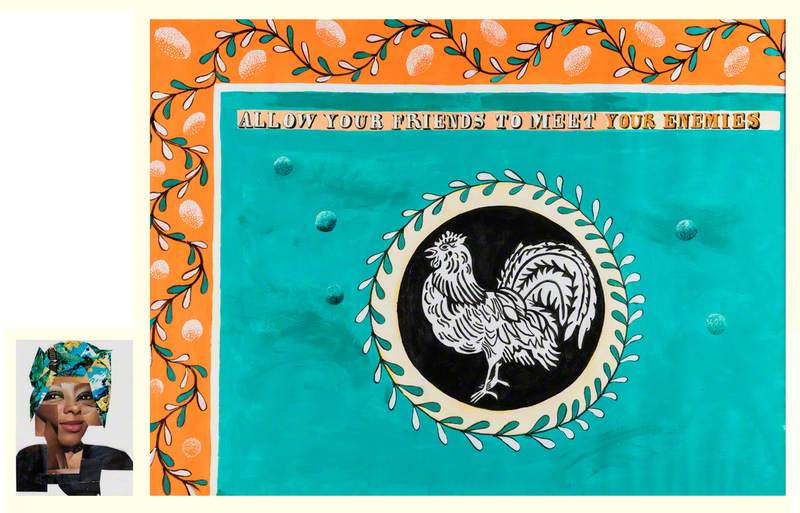

Lubaina Himid, 2017

In 2017, artist and curator Lubaina Himid received the Turner Prize, beating Hurvin Anderson, Andrea Büttner and Rosalind Nashashibi. A member of the UK’s black arts movement in the 1980s,

Allow Your Friends to Meet Your Enemies

(diptych, right and left panel) 2011

Lubaina Himid (b.1954)

We’re now at the end our brief Turner Prize history. Like J. M. W. Turner himself, the prize has attracted scorn and praise. Since its beginning, it has reflected contemporary culture, but has also unapologetically searched for fresh perspectives, new ways of making, and celebrates art that is challenging. What will the next thirty-something years of the Turner Prize look like? We'll just have to wait and see...

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK