There will be many who are familiar with the Grade II, 1886 statue of Queen Anne (1665–1714) with four allegories, at the foot of St Paul's Cathedral steps. What many will not realise, unless they take the time to read the inscription, is the fact that this monument is an almost identical copy of the original group created in the year 1712.

Like some strange instance of mystical bilocation, the original group, sadly now in a very neglected condition, emerges from undergrowth on wasteland at The Ridge in Hastings. This original monument, ironically with a Grade II* designation, is also on the Heritage at Risk Register.

Queen Anne (1665–1714) with Allegorical Group

1712

Francis Bird (1667–1731)

The story of how the monument arrived in Hastings is both convoluted and fascinating, and many aspects of its story have resonance with debates around public sculpture today.

The original statue was unveiled on 7th July 1713, and created by the sculptor Francis Bird, who had been responsible for several other works adorning St Paul's Cathedral. He had also been responsible for the 1706 statue of Queen Anne in Kingston upon Thames.

Plans for the monument were already in place as early as 1709, and it was eventually completed in 1712. The context of the site outside the cathedral was important, emphatically proclaiming not only Queen Anne's dominion over the Empire, but, as Head of State and of the Church of England, also over the contested location that was an important secular, commercial, and religious site.

At that time, there were still widespread challenges to the Anglican Church and, throughout her reign, Anne was passionate about combatting the influence of dissenters. In fact, this statue is the only portrait of her erected with her complete support. Plans were also put in place in 1713 to erect 50 new churches, each to feature a statue of Anne in a prominent position, although this initiative never actually came to fruition.

Commissioned by Sir Christopher Wren as an integral part of the design of St Paul's Cathedral, its unveiling was planned for 7th July 1713. This was to be an important part of the great Thanksgiving Service for the Peace of Utrecht (as part of those treaties, as well as Britain gaining other territories, Gibraltar was ceded by Spain). Queen Anne was unable to attend the unveiling however due to ill health and she died only one year after it was unveiled.

The figures on the monument were sculpted in Sicilian marble, and the entire monument has approximate overall dimensions of 6.5 metres high and 5 metres in diameter. Queen Anne, in a triumphal pose with crown, sceptre and orb, surmounted the central plinth with the allegorical statues of Britannia, France, America, and Ireland, arranged around the stepped base (originally the base was black marble). A cartouche with the Royal Arms sat upright at the front of the plinth, supported by Britannia's left hand.

As is frequently the case with public monuments today, even as it was unveiled, the monument was not particularly well received by everyone, being variously mocked and criticised by elements of the press and other writers. Some criticised the style for being 'old fashioned', some the vestments and the 'affected' pose. Others complained that it was actually a poor likeness of Queen Anne, and of course, the contested location was a point of annoyance and frustration for many. The Queen's own doctor, John Arbuthnot, is attributed with the often quoted, 'Brandy-faced Nan, who was left in the lurch, with her face to the gin-shop, her back to the church'.

The monument did not fare well over the next 150 or so years and criticism of the work continued; in 1803 for example, James Malcolm wrote in his Londinium Redivivum that, 'the wits of the day were very severe upon it', and refers to it as an 'ill contrived and tasteless group'. It also seemed to attract repeated acts of vandalism, at least twice by people who were termed of 'unsound mind' at their trials. One such attacker, armed with a 'chopper' and a hammer, severely damaged the statue in 1882, asserting that he had done it because Queen Anne was his mother, and the Duke of Wellington was his father!

As early as the 1870s, there were already concerns about the deteriorating condition of the statuary, resulting in suggestions that it should be renovated or actually removed. A letter to the London Reader in 1874 complained: '"Clear it away! Clear it away!" This seems to be the cry of the day. Everything that does not quite meet our views, that is not exactly in the style we happen just now to approve of... is to be demolished and done away with... If every succeeding generation is to sweep away the memorials raised by that which preceded it, history will have no landmarks.' Sound familiar?

There was general agreement however that something needed to be done about a deteriorating monument in such a prominent position. Not unlike the situation with many works of public sculpture today, the actual ownership of the statue, and therefore who was responsible for it, and the costs of repairing it, was very difficult to ascertain. Eventually in 1884, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London, and the Lord Mayor approved the commissioning of a replacement and in 1885, the sculptor Richard Claude Belt was employed to recreate the original statuary.

Richard Claude Belt

1882, albumen carte-de-visite by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company

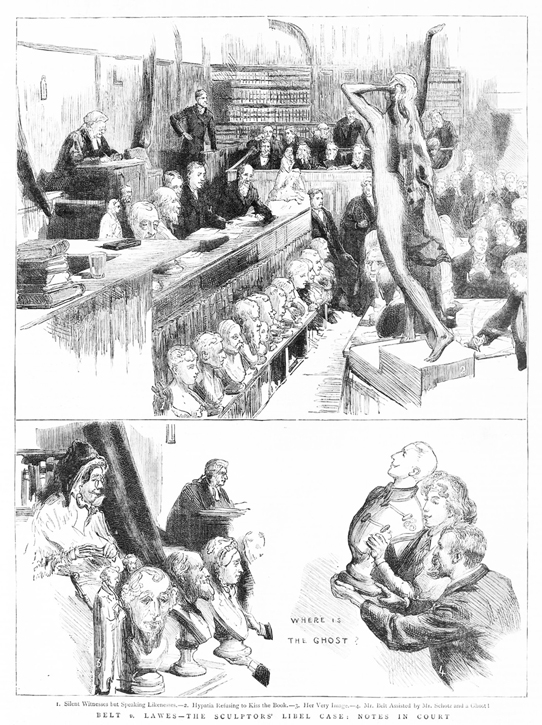

The choice of Belt was extraordinarily controversial as in 1882 he had been involved in a fascinating and famous libel case, against the sculptor Charles Lawes (later Sir Charles Lawes-Wittewronge, whose The Death of Dirce stands outside Tate Britain). The case was brought because of accusations by Lawes, in Vanity Fair, of Belt undertaking 'very scandalous deception' in using a 'sculptor's ghost' in the creation of a monument to Lord Byron on Park Lane.

George Gordon Byron (1788–1824), 6th Baron Byron

1880

Richard Claude Belt (1851–1920) and Thames Ditton Foundry (active 1874–1920)

Pierre François Verheyden, who had been an assistant in Belt's studio, was named as the primary 'ghost' in question. The accusations questioned the professional skills of Belt as a sculptor and the trial became a cause célèbre, widely covered in the press. A great many sculptures were used as exhibits in order to analyse Belt's self-professed skill, and some of the greatest sculptors of the day were called to give evidence. The notion of studio assistants, or 'ghosts', creating artworks carrying the name of well-known artists, is not something we are strangers to today, of course.

Belt v Lawes: The Sculptors' Libel Case

From 'The Graphic', 18th November 1882

At the end of the trial, the jury found for Belt, and he was awarded £5,000 damages – the highest ever previously awarded in a libel case. The damages were reduced following subsequent appeals, but in another twist of fate, they were reinstated by yet another one! The artistic community had been outraged at the judgment, most of them firmly siding with Lawes. As a result of the initial damages and subsequent appeals, Lawes was bankrupted however, and unable to pay Belt's expenses, which in turn also forced him into bankruptcy. Belt was never subsequently able to quite shake off the infamous moniker, 'the charlatan sculptor'.

The libel trial directly influenced the creation of the Society of British Sculptors in 1905; in a twist of fate, Sir Charles Lawes-Wittewronge was elected its President in 1909 and successfully petitioned George V to add 'Royal' to its title.

The original monument was eventually removed from St Paul's Cathedral on 2nd September 1885 – even in the week of its removal The Morning Post was referring to it as a 'monstrosity', and referencing other 'monstrosities in marble' by Francis Bird.

Richard Belt had made a start on the replica group but, in 1886, he was convicted of 'conspiracy to obtain, and of obtaining money from Sir William Abdy by false representations'. He, and his brother, had sold jewellery at inflated prices to Abdy, purporting to have come from a Sultan. The jewellery had in fact come from a pawnbroker. His brother was acquitted, but Belt was sentenced to a twelve-month prison sentence with hard labour, a result that caused much pleasure among the sculptors who had supported Lawes in the famous libel trial.

As a result of Belt's imprisonment, the sculptor, Louis-Auguste Malempré was employed to complete the work on the replica Queen Anne monument. In some press reports, it was alleged that Belt had continued to work on the sculpture while he was in Holloway Gaol, but this was patently untrue and Malempré was instructed to write to the press demanding an official retraction. Queen Victoria herself also demanded that this assertion was retracted in the press.

The unveiling of the new monument took place on 15th December 1886.

When Belt was released from prison he had demanded that his name be put on the monument as the sculptor, despite the fact that he had never personally carried out any of the work on the monument. This did nothing to quell accusations of him being a 'charlatan'.

It is interesting to note that, even after the original monument was replaced with the replica, there were still frequent calls for it to be removed. As early as 1897, the Diamond Jubilee year of Queen Victoria, she was asked for permission to move it, replying, 'Move Queen Anne? Certainly not! Why it might some day be suggested that my statue should be removed, which I should much dislike.'

For years after the original monument had been quickly removed during the night, the travel writer Augustus Hare searched for its location with no success. Then one of his friends noticed the statues sitting in a stone mason's yard near Vauxhall Bridge Road. The mason had been instructed by the City Council to sell the works for the value of the marble but, Hare discovered that they had no right to give any orders concerning the work as it belonged to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London, and the Lord Mayor. Hare purchased the work himself and made arrangements for it to be taken down to Holmhurst, his home in Hastings.

The monument was laboriously transported, with great spectacle, to Holmhurst by road, using 28 horses, four trucks, four trollies, and 16 men. A circuitous route had to be found for the procession in order to avoid low bridges and tunnels, because it was impossible to lie Queen Anne on her back, both because of her long train, and because it was also deemed unseemly to do so. The statue of Queen Anne, therefore, led the procession, leaning slightly forward to accommodate the train, and each of the other four figures were in separate wagons following behind.

Hare restored the monument beautifully in the extensive gardens at Holmhurst, creating a new stepped base in stone to replace the original black marble one. When Hare died in 1903, Holmhurst was purchased by Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Beaumont, and subsequently by Sir John Gordon Kennedy, but it was later acquired by the Community of the Holy Family, who founded a school dedicated to the teaching of women of all ages, worldwide, and that was founded expressly for scholars and artists. One notable attendee at the school is Joanna Lumley.

The school was closed some years ago and the main house has already been converted into luxury flats. The land on which the monument to Queen Anne stands is currently in the hands of developers who have had to make a commitment to restore the monument and provide public access to it. It is currently covered by a large metal structure although vandals have continued to cause enormous damage to it and it is now in a very sorry state.

What a great pity that a monument with such an extraordinary history is not better looked after by both local authorities, and developers. Its Grade II* listed status and its inclusion on the Heritage at Risk Register has apparently done little to protect it from gross neglect and continued wanton vandalism.

Anthony McIntosh, Public Sculpture Manager, Art UK