The Scottish Fisheries Museum in Anstruther, Fife, holds an important collection of more than 66,000 objects that tell the story of the country's fishing industry, including a varied and significant collection of artworks.

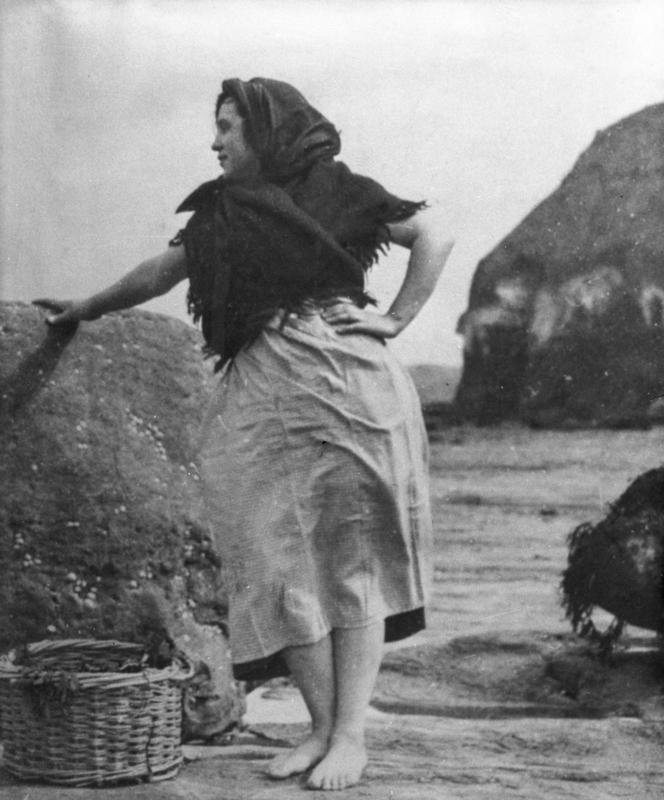

We have recently added some of our photography to Art UK, allowing us to highlight the important and sometimes unacknowledged role women played in the fishing community.

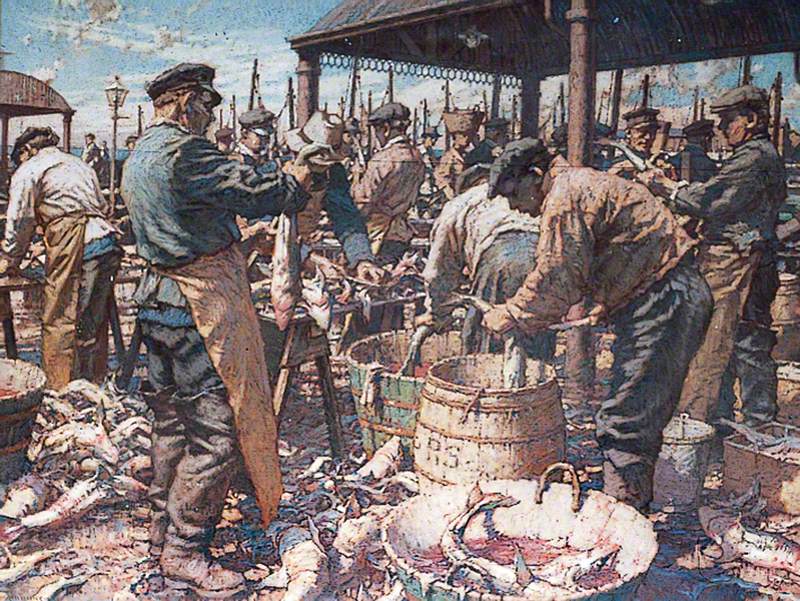

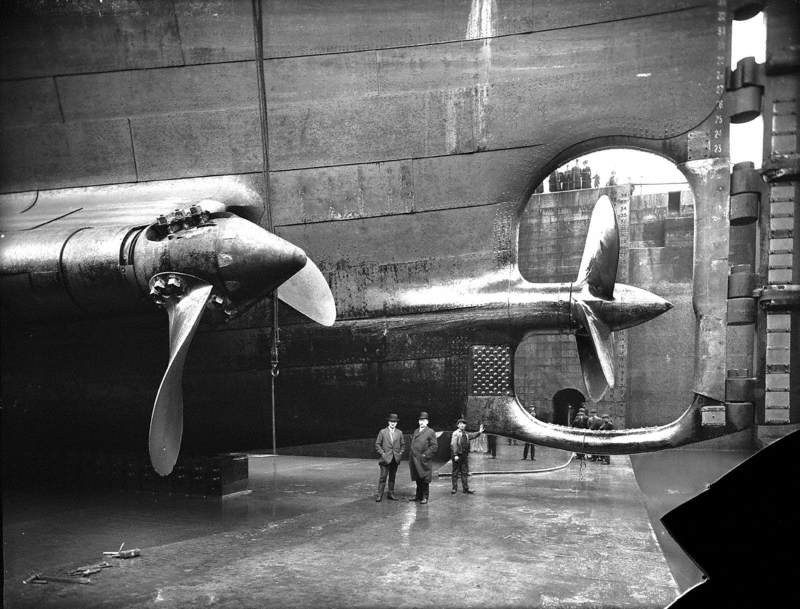

By the mid-nineteenth century, many fishing towns and villages were established around the coast of Scotland. At the peak of what is called the 'herring boom' in 1907, 2.5 million barrels of fish (250,000 tons) were caught, cured, gutted and packed, before finally being exported by thousands of Scottish workers from all over the country.

Each year, fishermen travelled down the coast, following the herring shoals all the way from the Hebrides on the West Coast of Scotland in May, to Northumberland and Yorkshire, which they reached by mid-September.

From October to December they were in Yarmouth and Lowestoft, and some boats even partook in a winter fishing season in the Forth near Edinburgh, in the Minch between the Hebrides and the Scottish mainland, in the Irish Sea and off Northern Ireland from January to March.

'O for Yarmouth bustle and hurry,

Time for nothing but making money,

But still it has its little joys,

Hippodrome, theatre, Gem and Boys'

– Elizabeth Bain, Nairn herring lass

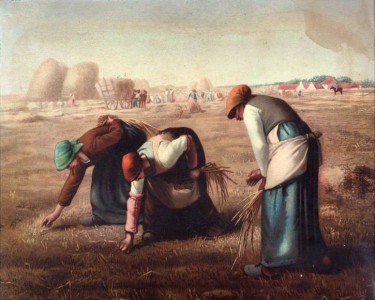

Although it was the men who did the fishing, women played an equally crucial part: each year, 6,000 Scottish herring lasses travelled from port to port to gut and pack the herring, or 'silver darlings' as they were also called. Being away from home months at a time, they packed with them a kist – a wooden chest containing all their belongings for the season.

These would have included both working and Sunday clothes, sheets and towels, knitting equipment, and a gutting knife (or futtle), and bandages, also known as cloots, to tie around their fingers to protect them from cuts.

These bandages, often made from flour bags, did not always provide the cuts sufficient protection from the salt and the brine which would make the work extremely painful.

In her article on the topic, Margaret H. King called this distribution of labour a 'partnership of equals'. Due to the efforts women put in, they were considered equal to men in the fishing community.

In addition to the gutting and the packing, herring lasses also contributed in many other ways to the work of the fishing industry by cooking and cleaning for the men, mending nets and, in some instances, cleaning the boats.

Herring lasses also enjoyed more financial freedom than some of their contemporary counterparts by earning their own wages, and, by travelling for work for months at a time, they also experienced some social freedoms as well.

Herring is an oily fish, and for this reason, needs to be cured within 24 hours of being caught to prevent it from rotting. This often meant the lasses working at least twelve-hour days from six in the morning to six in the evening, or even as late as nine, or sometimes up to midnight. This was done to earn the coveted 'Crown Brand', the highest quality branding for Scotch-cured herring.

Due to the dirty nature of the work, dressing appropriately was key. The lasses wore oilskin aprons that overlapped at the back, a blouse and a cardigan or sweater to keep warm, and leather boots up to knees to protect them from fish guts.

As their work clothing got particularly mucky and potent after a hard day's work, the women would often change their clothing at the harbour, which caused outsider onlookers to question their morals.

Herring gutting and packing was hard, physical work that was balanced by an active social life and gatherings. The boats' crews were often men from the same towns as the women, and many herring lasses met their future husbands during the fishing season.

One Shetland herring lass described the life as follows:

'We never worked on Saturday nichts because dat wis da nicht we gied ta da dance ... we wid geng oot an we wid be picking da scales aff wir arms as we gied alang, an wi da heat a da ballroom da chaps smelt da herring in wir hair. It didna matter how much time we washed wir hair, it alwyes smelt ...'

– Christina Jackman

The booming herring fishing industry began to wane after the First World War. A comparison of the numbers of migrant herring lasses in 1920 and 1938 show a drastic decline from about 9,000 workers to 4,500. In 1962, only ten women worked the Yarmouth season.

Over-fishing in the 1940s and 1950s led to a nationwide ban on herring fishing in 1977, which lasted until 1983.

How then are the women in this industry remembered? Since its establishment over 50 years ago, the Scottish Fisheries Museum has housed a collection of over 66,000 objects relating to the country's fishing industry.

Consisting of boats, tools, domestic items and photographs to list a few categories, the stories of the herring lasses are perhaps most beautifully told and appreciated through works of art.

Due to the dirty nature of their work, these women and their fisherfolk families were sometimes considered lesser people by their more urban counterparts – whether this was more a class issue than specifically related to the fishing industry can be debated.

To counter this view, to some extent, there are also romanticised contemporary depictions of 'bonnie' fisherlasses with their colourful petticoats and rosy cheeks.

Due to these contradicting historical perceptions, we wanted to share these oil paintings showing both the women and work and some eloquent portraits.

Minna Kajaste-McCormack, Assistant Curator (Collections), Scottish Fisheries Museum