For many, it would top a chart of romantic paintings even though The Death of Chatterton by Henry Wallis (1830–1916) was almost a 'one-hit wonder'.

His depiction of the boy poet Thomas Chatterton (1752–1770) in a garret beside an empty phial of arsenic and a pile of destroyed jottings caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856.

The brilliantly composed image of the lifeless young genius driven by neglect and despair to suicide was, in John Ruskin's view, 'faultless and wonderful' and remains a popular attraction at the Tate with two smaller versions at Birmingham Museums Trust and the Yale Center for British Art.

Like many a pop star, though, Wallis' career had peaked almost before it had begun. Produced at the age of just 26, his defining work was the catalyst for a second tragedy which culminated in another premature death.

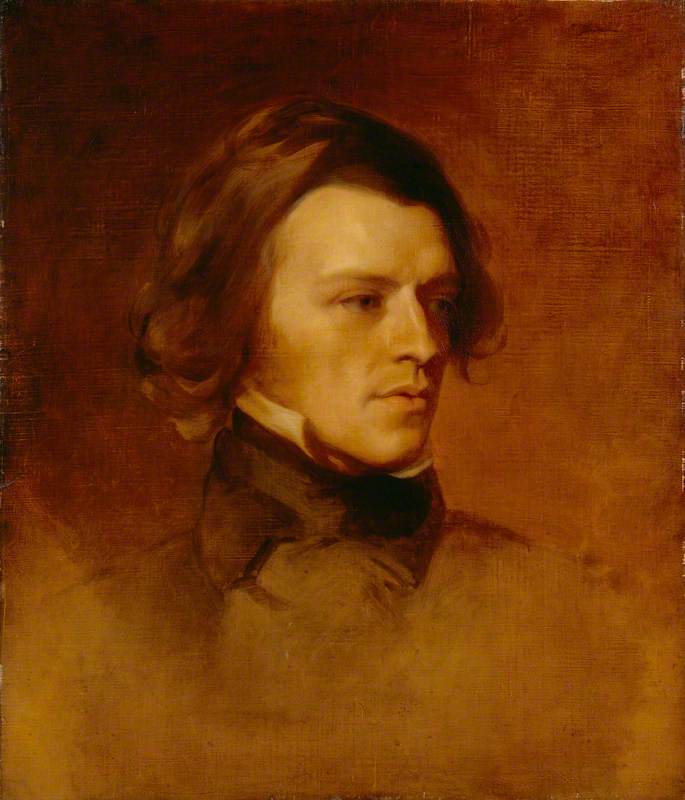

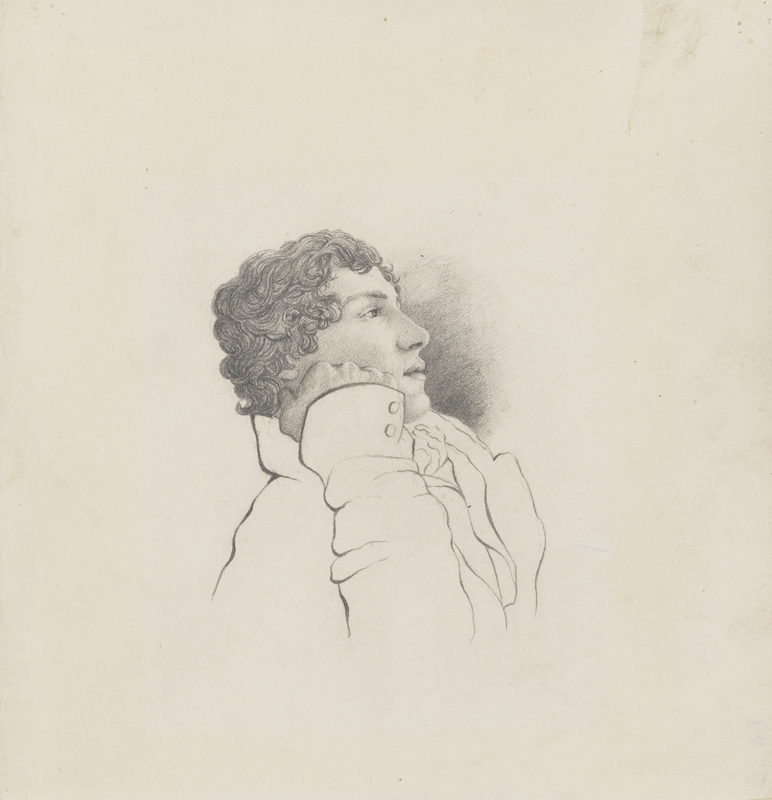

Wallis used a writer friend, George Meredith (1828–1909), as a model for Thomas Chatterton – although, at 27, Meredith was a decade older than the precocious poet.

It was a fateful choice for soon after finishing his masterpiece Wallis and Meredith's wife, Mary Ellen began an affair.

The daughter of the writer Thomas Love Peacock (1786–1866), Mary Ellen was a lively, independent spirit who kicked against the gender inequalities of the Victorian age. She was a talented writer and, as sketches of her by Wallis show, strikingly good looking.

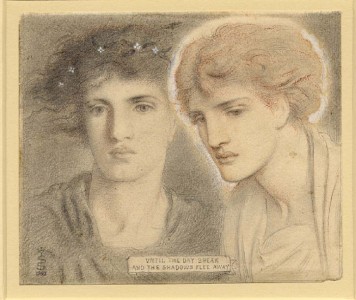

Portrait of Mary Ellen Meredith (1821–1861)

c.1857, pencil on paper by Henry Wallis (1830–1916)

Mary Ellen's first husband, Lieutenant Edward Nicolls, a marine, had drowned in 1844 before the birth of their daughter Edith. Five years later she married George Meredith with whom she had a son called Arthur.

By most accounts the couple's first few years were happy but by the time of Chatterton the relationship had soured. Wallis had painted Mary Ellen in a lost work called Fireside Reverie in 1854. It was probably a few years later at Seaford on the Sussex coast that their affair began.

George Meredith had mixed feelings about the seaside town. Writing to a friend he lists the attractions of 'fishing, bathing, rowing, sailing, lounging running and pic-nicing', but later describes their lodgings as 'a straggling row of villas facing a muddy beach.' In contrast, Wallis, ever the Romantic, painted Seaford under a glorious sunset.

In 1857, a year after Chatterton, Wallis, returned from a continental trip and is thought to have taken the ferry from Dieppe to neighbouring Newhaven. George was away and Mary Ellen invited Henry to stay.

The details of the affair can only be guessed at but we know Henry and Mary Ellen later spent time together in Wales and Capri.

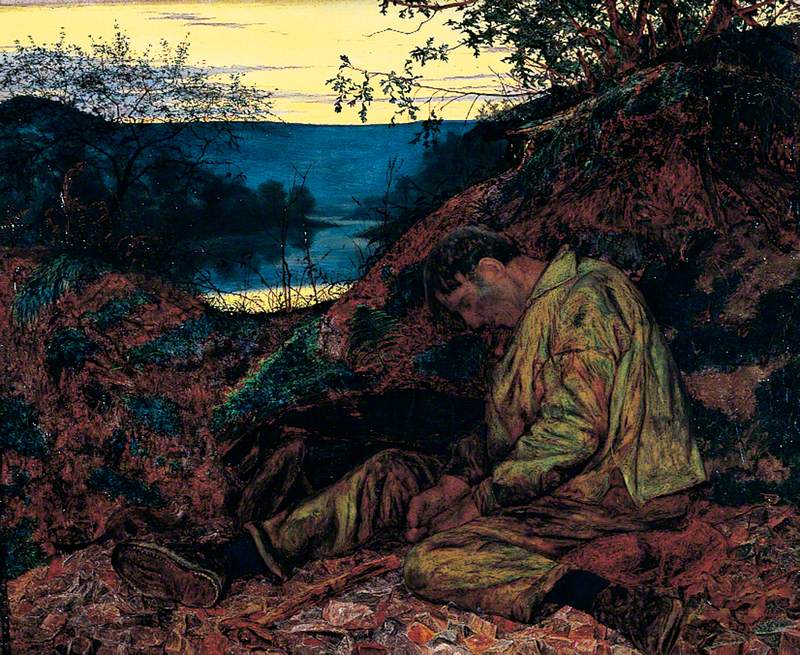

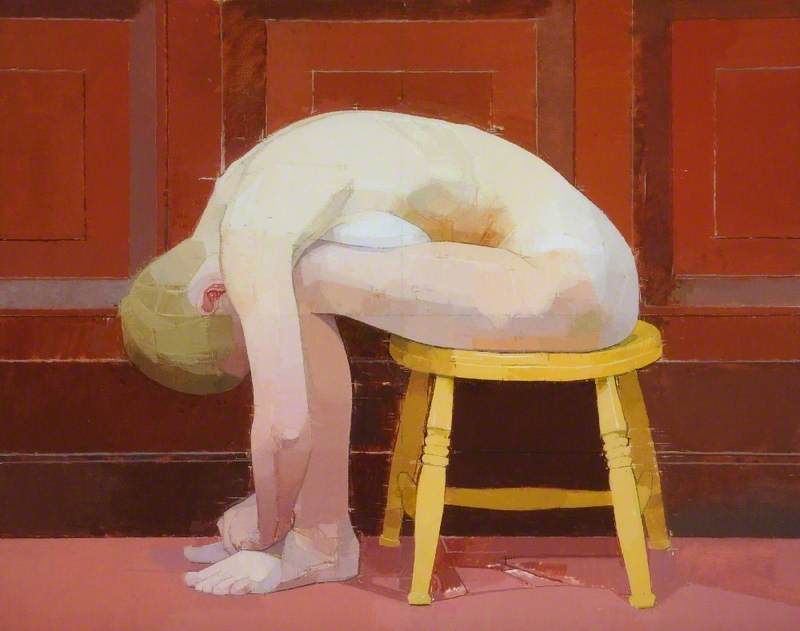

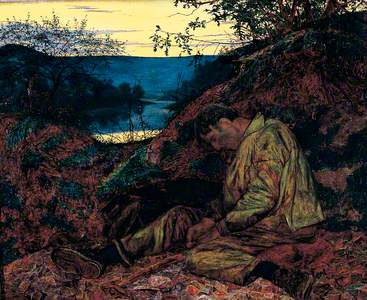

Henry's second, and last, notable success was another tragic tableau called The Stone Breaker which may have been painted while he was with Mary Ellen in Wales.

It shows a young man worn out by manual work. A hammer has slipped from his grasp, a stoat, barely visible, has climbed on to his right leg. He looks, and probably is, dead. There are few more powerful works of social realism in the Pre-Raphaelite era.

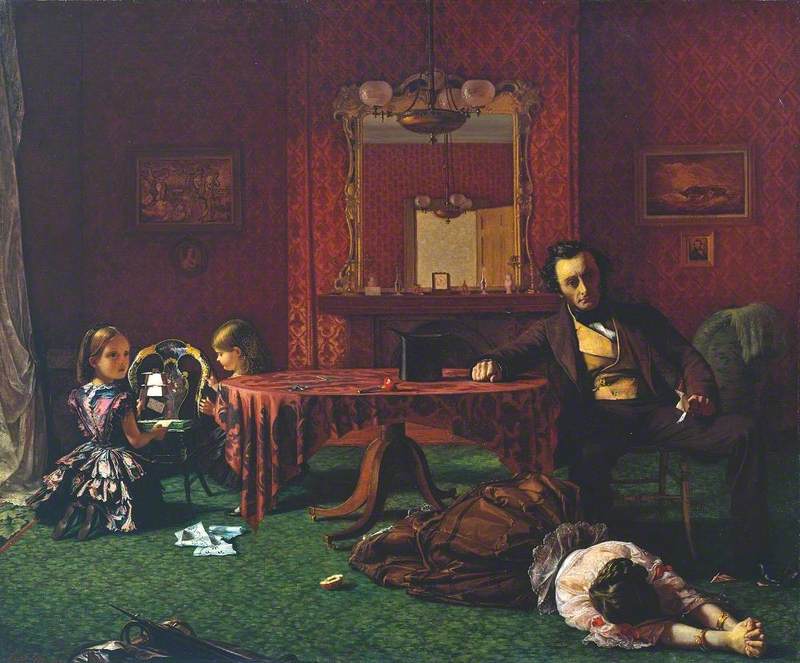

Much to the humiliation of Meredith, news of Henry and Mary Ellen's affair soon spread among artistic circles. By 1858 she had given birth to a boy called Harold. Although Meredith's name was on the birth certificate, Wallis was the biological father. In an act which some have interpreted as revenge Meredith removed the older boy Arthur from his mother's care and he barely saw her again.

Wallis, a genial and independently wealthy man, seems to have been welcomed by Mary Ellen's family. He produced a portrait of her father Thomas Love Peacock who was said to have much preferred him to Meredith.

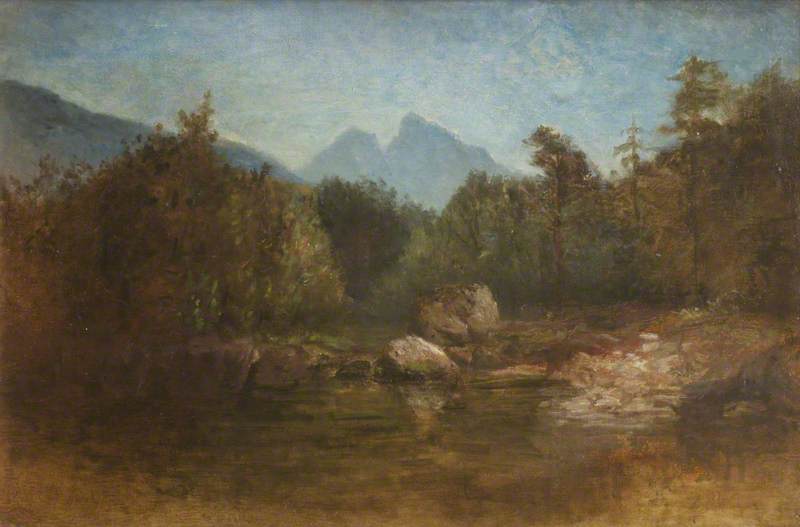

Unfortunately, Mary Ellen's health declined and, in the hope of a recovery, in 1858 Wallis took her to Capri, then a popular resort for writers and artists. Wallis' friend and exact contemporary Frederic Leighton (1830–1896) painted this image of the island around that time.

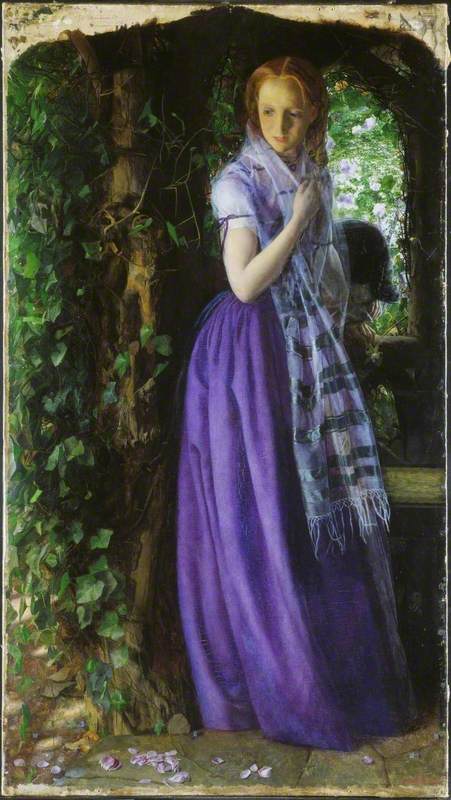

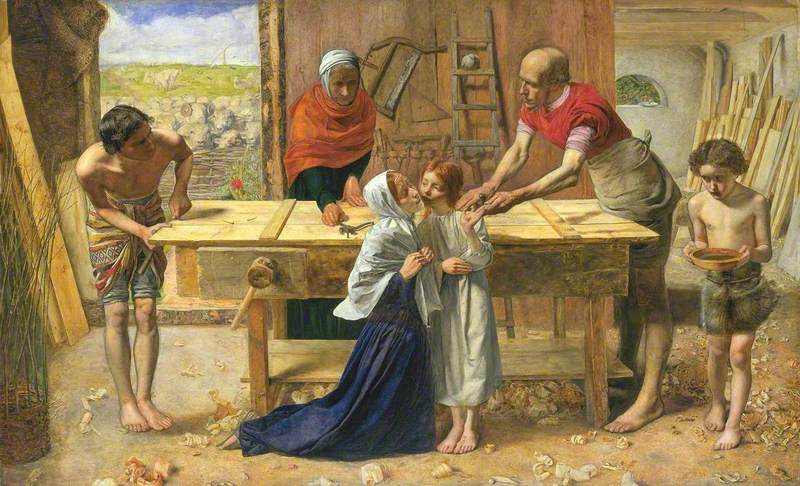

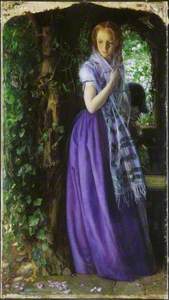

Both Leighton and Wallis were members of the Hogarth Club, an exhibiting society (1858–1861) founded by former members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood including Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882). Another member was Wallis' lifelong friend Arthur Hughes (1832–1915) whose most famous painting April Love was shown at the Royal Academy in the same year as The Death of Chatterton.

Both painters favouring purple for their subjects' principal garments.

Sadly the trip to Capri failed to improve Mary Ellen's health and she died from kidney disease aged 40 in 1861. Neither Wallis, Meredith nor her father attended the funeral. During her lifetime, and for many years after, Mary Ellen was condemned for bringing shame on Meredith but later accounts, notably the recently reissued The True History of the First Mrs Meredith by Diane Johnson, have been more balanced and sympathetic.

Meredith remarried and became one of the country's most celebrated men of letters winning the literary fame that poor Thomas Chatterton had craved. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature no fewer than seven times. His failed relationship with Mary Ellen inspired a poem called Modern Love and several of his novels, including The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, mined the theme of faithless wives.

His poem The Lark Ascending inspired Ralph Vaughan Williams' violin composition of the same name which in 2021 topped the Classic FM Hall of Fame poll of the nation's favourite classical music for the eleventh time.

While never fulfilling his early promise, Wallis raised Harold, kept in touch with Edith and outlived Meredith. After the painter's death, a green gown worn by Mary Ellen was found among his possessions.

James Trollope, writer and columnist