If art is part-representation, then portraiture is representation writ large.

Many nations tell their origin stories in these forms, from cave paintings of animals and hunting scenes, to skilfully wrought depictions of momentous battles and the personalities that shaped the national destiny.

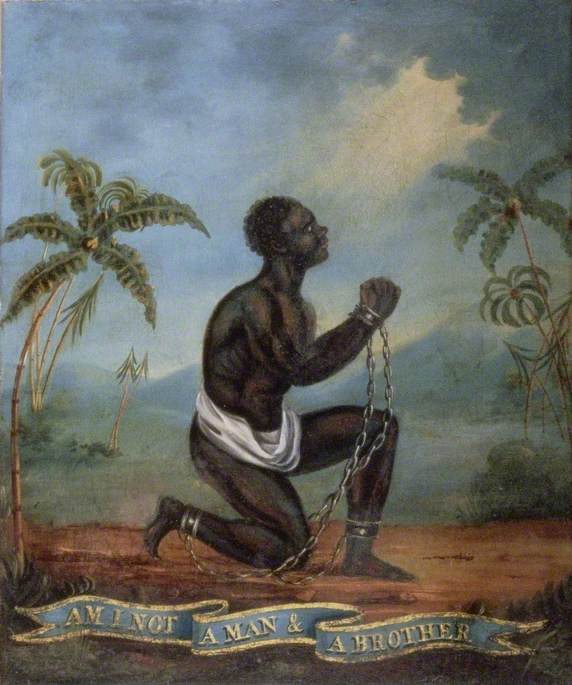

In the case of European art, there's a vital colour that's missing from many of these depictions of our national stories. An example from the UK is the outrageous neglect in the identification of the ordinary African-Britons who have been an integral part of this nation's history since Roman Britain days.

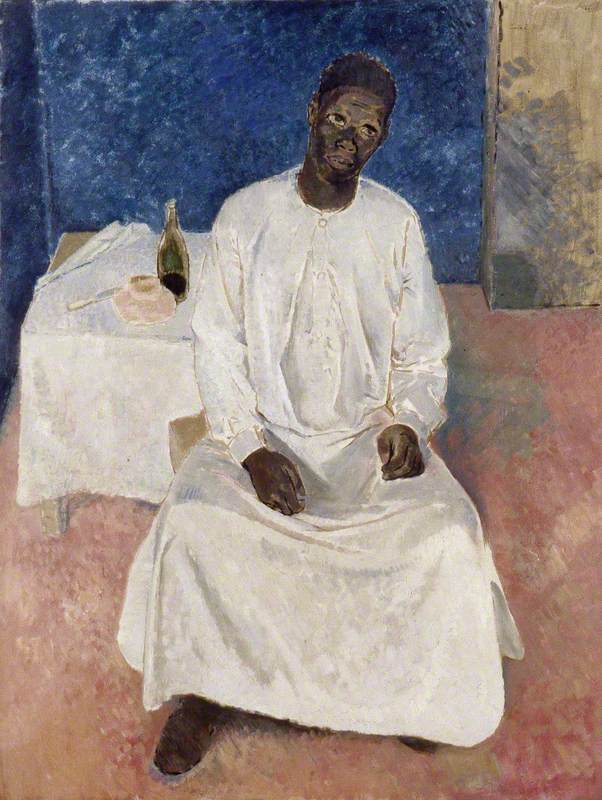

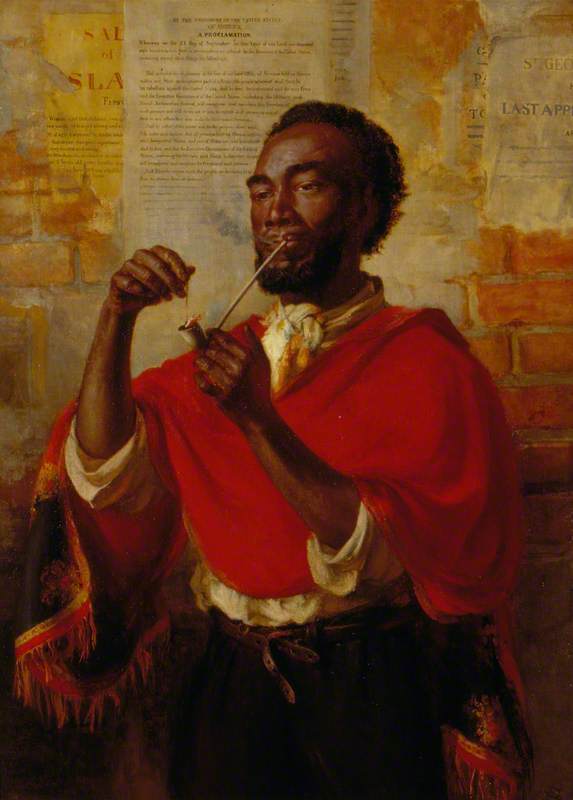

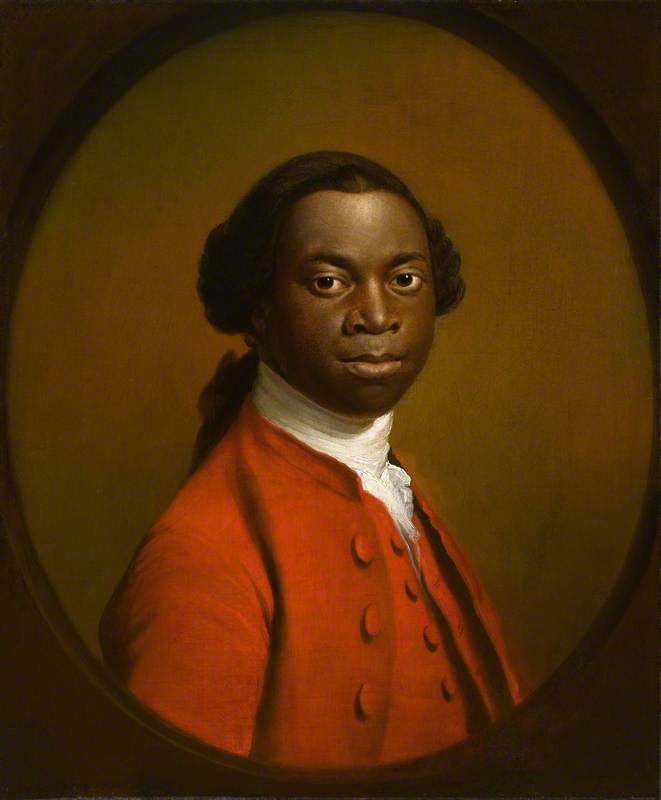

Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit

(formerly 'Portrait of an African') c.1740–1780

unknown artist

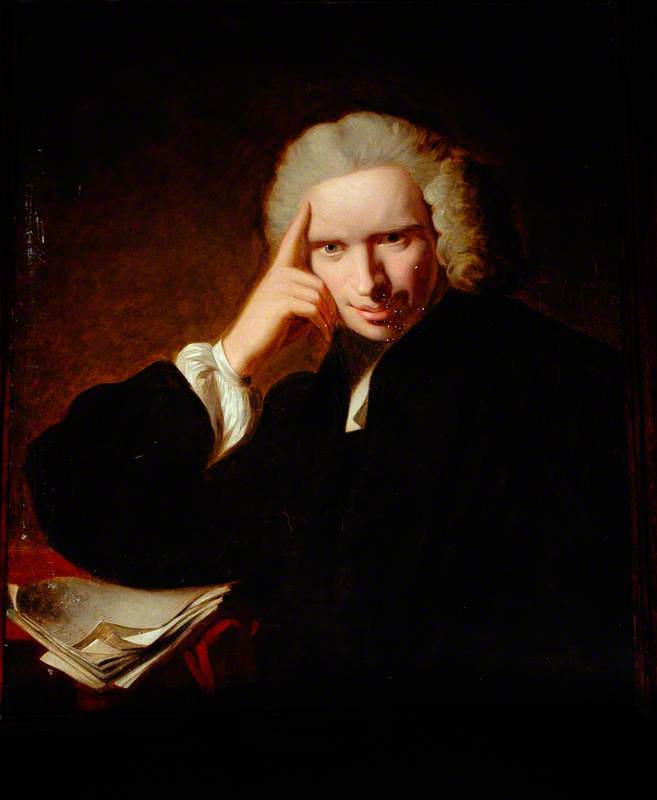

It is an act of snow-blindness that continues to this day. This month, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) have kindly ceded to my request, made through Art UK, to re-examine former curator John Madin's suggestion that Allan Ramsay's Portrait of An African no longer be bracketed with 'probably Ignatius Sancho'.

Having lived with Charles Ignatius Sancho's story for the last 20 years (and authoring the play Sancho: An Act of Remembrance), my outrage on seeing this attribution in the August 2006 edition of Apollo magazine being treated as factual, was fierce. My rage was defused somewhat by Art UK's swift response and promise that the bracketed comments, an opinion, would be removed from the portrait on their website, and the collection informed.

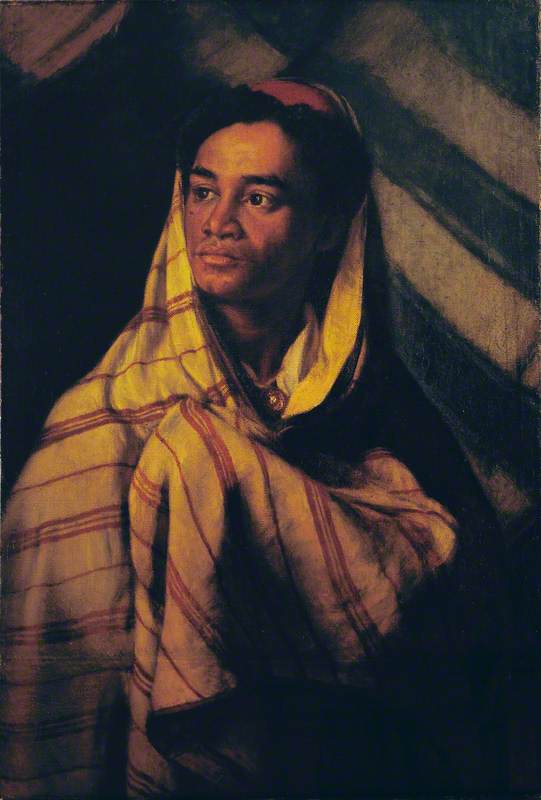

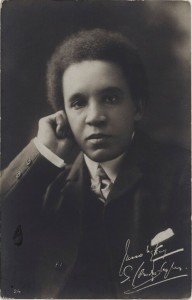

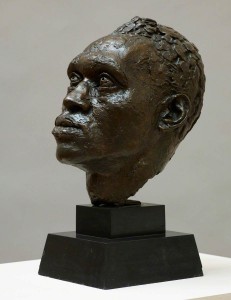

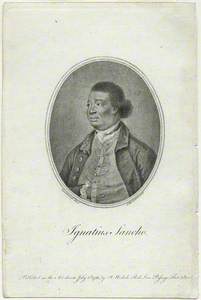

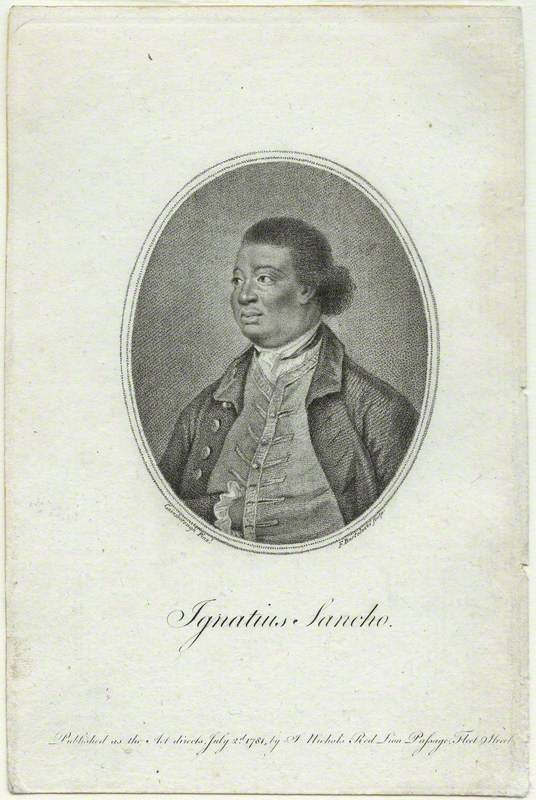

Ignatius Sancho

1768, oil on canvas by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

But this has thrown up yet more questions for me, in many ways.

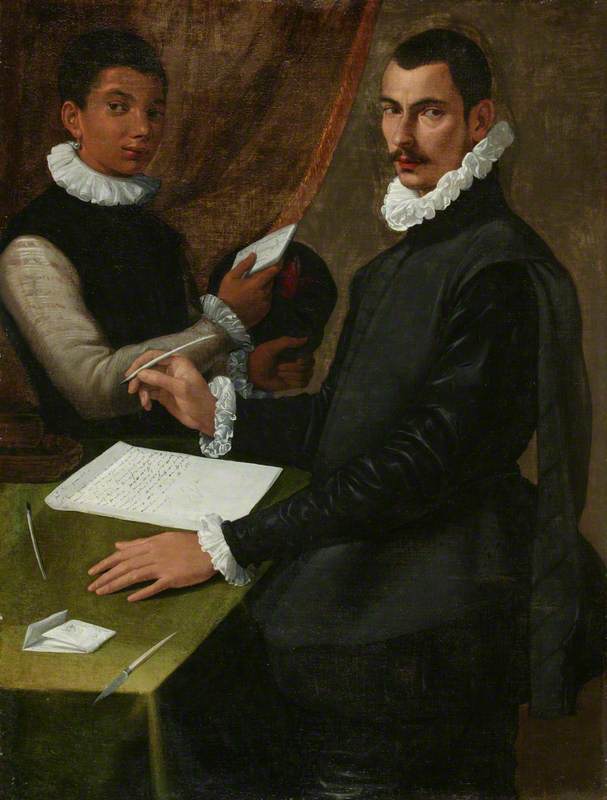

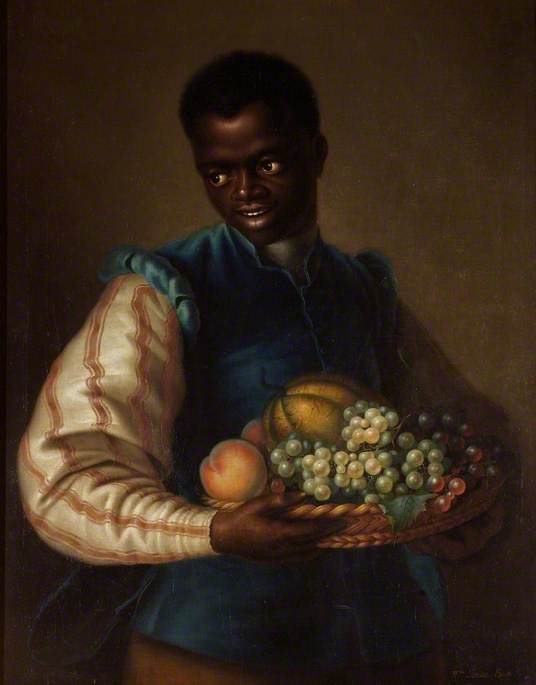

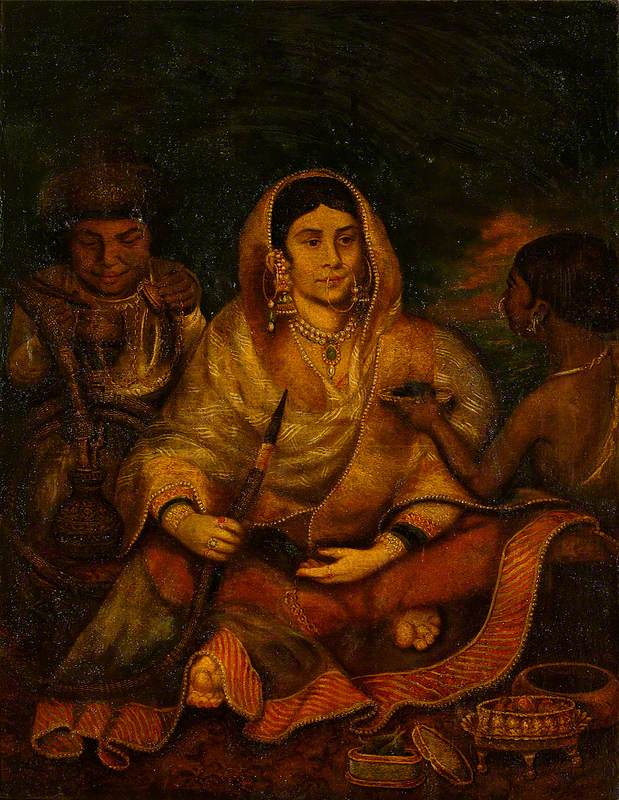

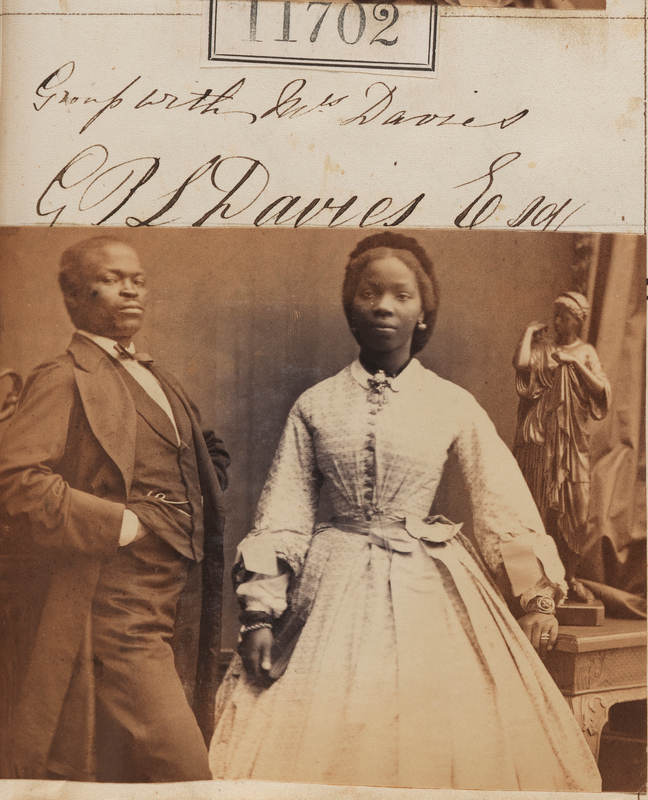

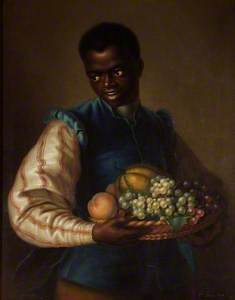

Why, for example, do we have hundreds of portraits from the seventeenth century onwards that depict European subjects who are named fully – as well at times as their pet dog or horse – and the black child next to them in these portraits, merely called 'A Negro' or 'and Servant'?

If this is not racism and an objectifying, dehumanising of an entire ethnicity, I cannot define it at all. I call on the international art community to cease this practice of lazily continuing to objectify children who were not named – for painfully obvious reasons – in the past.

I urge them to make every effort to properly conduct investigations to identify and name these people, at the very least acknowledging their ignorance and willingness to discover their identities. Thus, in some small way, affording them a little dignity in their obscured lives and deaths. If they do not do this, they perpetuate the idea that black people may have contributed to the riches of Europe and America but are in no way worthy of being acknowledged as the human beings they were.

Here, African-Britons have largely been whitewashed from the record of British art history, simply because those charged with recording this history were not minded to include them, with notable exceptions.

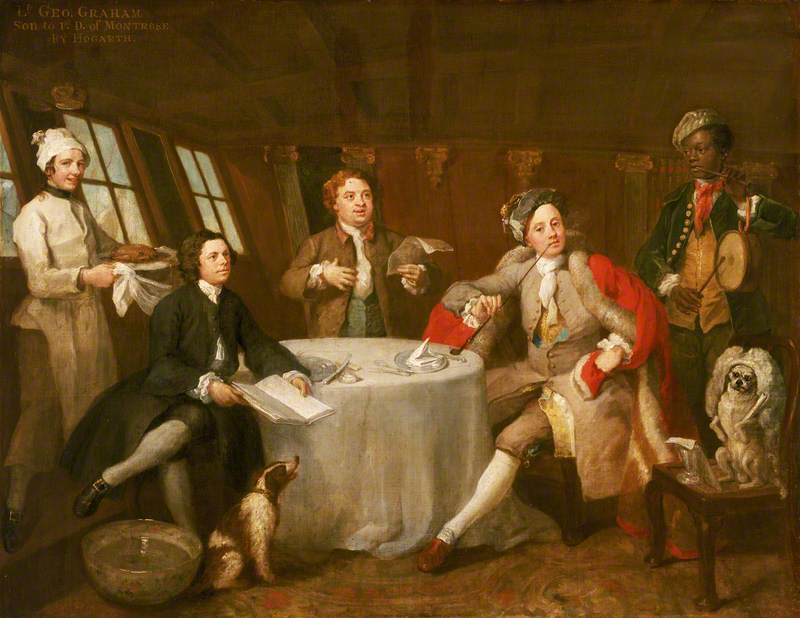

David Martin's Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Elizabeth; Thomas Gainsborough's dazzling Sancho portrait of 1768 (seen above); and political satirist and artist William Hogarth's anonymous but very present black witnesses to name a few.

Marriage A-la-Mode: 4, The Toilette

about 1743

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Sancho's remarkable story, that he was the first published African-Briton; worked around the Georgian court; became the first black man to receive an obituary in the press; participated in a parliamentary election in 1774 and then, finally, in 1780 – becoming the first, known, African-British voter to do so – makes him an exciting subject in any age.

Ignatius Sancho

(after Thomas Gainsborough) published 1781

Francesco Bartolozzi (1727/1728–1815)

Sancho's correspondence with the writer Laurence Sterne was held up as an example to the burgeoning anti-slavery movement of the potential for articulate protest from educated African-Britons. This coverage of a black, British hero makes Charles Ignatius Sancho an exception in history.

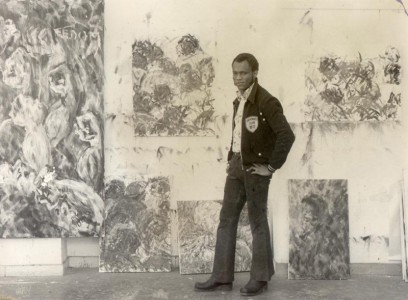

However, as we know, exceptions do not make history alone. Wherever I meet art historians, invariably white, handling the long eighteenth century they – near-universally – ignore the less 'notable' black people who were very present in that century and beyond. Why is this?

Racism is not the easy answer, though it clearly plays its part. The main issue is one of interest. If one is not taught that a people matter, then it is left up to that individual to discover this themselves. A rather ad hoc approach to any study in my opinion and subject to falling into negatively-biased ethnic thinking. 'They' are not us; 'they' are not important to 'our' story; 'they' do not matter.

George IV (1762–1830), when Prince of Wales

(after Joshua Reynolds) 1780

John Hoppner (1758–1810)

As Hammad Nasar noted in his excellent Art UK article The bureaucracy of artistic Britishness: 'As we steel ourselves to navigate a new path through our global relationships in a post-Brexit Britain, it may be worth our while to invest in recognising our expansive histories, and addressing the paucity of cultural stories and collections that allow us to fully imagine an idea of Britain that is capacious enough to embrace all who think of it as home.'

The pitfall of snow-blindness, clearly, lies in our teaching of art history too. If our scholars are being given a skewed, mono-chromed vision/version of the European art story and, in my opinion, therefore, of European history, then, perhaps inevitably, they are subsequently – from their university days – loudly and confidently in danger of rehashing the same snow-blind view that their own teachers grew up with; forming a vicious, if unintentional, very definitely racially-biased circle.

An Unknown Man, Perhaps Charles Goring of Wiston (1744–1829), Out Shooting with His Servant

c.1765

unknown artist

Black people in portraits of the great and the good do not matter, because they are 'nobodies'. This Euro-biased view of the nation's pictorial story is so prevalent, that it becomes embarrassingly clear that racism is institutionalised in our most prestigious art establishments. How else can this snow-blindness be explained?

I hope that incidences like the recent outrage over the lazy misidentification of Ignatius Sancho will be less prevalent in the future and, more importantly, that these young subjects in European portraiture will become an urgent study of identification by the new generation of art historians.

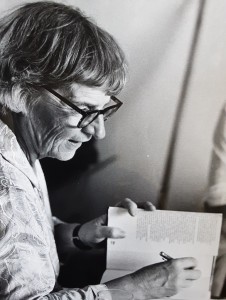

Paterson Joseph, writer and performer

You can find out more about the portrait in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in this Art Detective discussion

John Madin has responded to the points raised in this article

Further reading

Jenny Cooper and Miranda Kauffman's 'Black Tudors Bibliography'

Michael Ohajuru 'Black British History'

Jeff Green www.jeffreygreen.co.uk

Jan Marsh's blog 'The Black Subject: Tate Britain'

Leslie Primo's website

Caroline Bressey and The Equiano Centre's 'Black Londoners 1800–1900'