Artists have aimed to capture the mysterious beauty of the night sky for many different reasons: scientific advancement, to wonder at the heavens and how they came into being, or just for the pure joy of it.

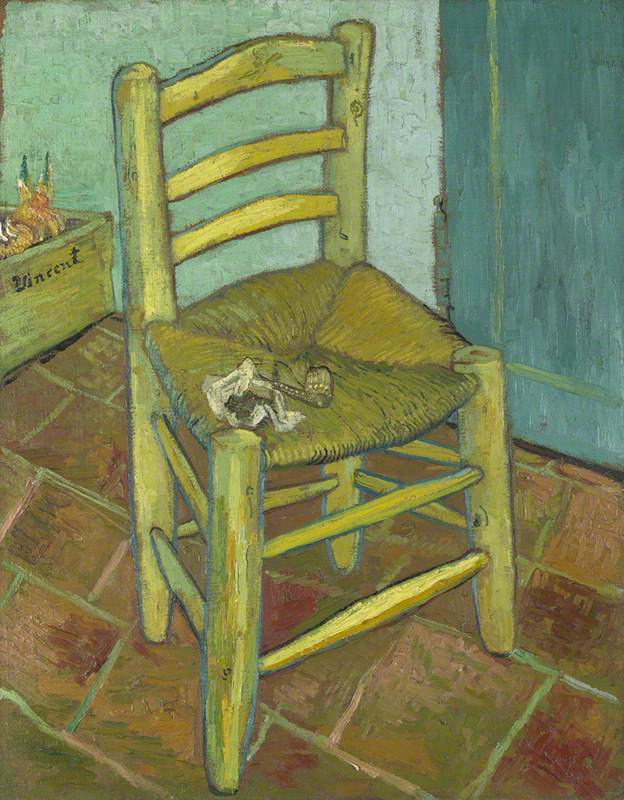

The most famous example is likely the psychedelic swirls of Vincent van Gogh's The Starry Night, housed in New York's MoMA.

The Starry Night

1889, oil on canvas by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

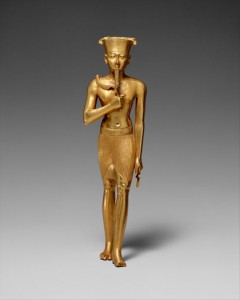

From recording cataclysmic events like comet strikes to plotting out patterns, people have always used art to interpret the celestial bodies' movements. The earliest known depiction of the cosmos, the 3,600-year-old Nebra sky disc, shows instantly recognisable golden moon and star shapes on a shimmering blue-green copper background.

Nebra sky disc

c.1800–1600 BC, copper & gold, Early Bronze Age Unetice culture

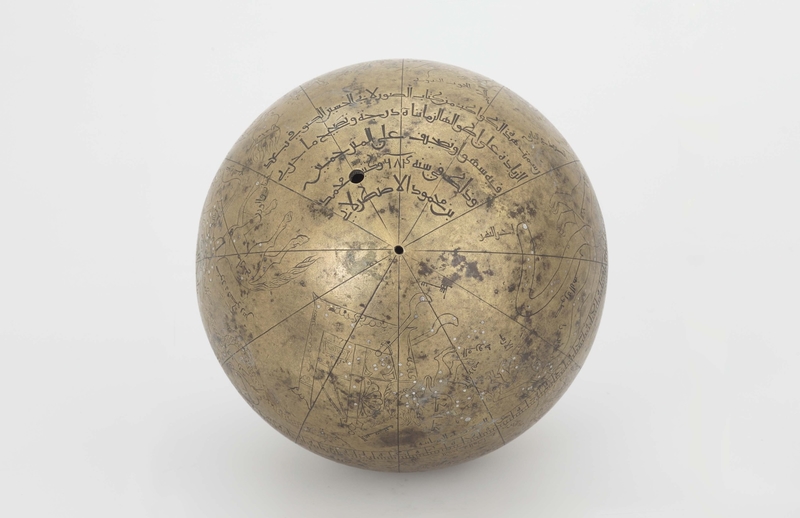

Instruments like the Khalili Collection's 700-year-old celestial globe were crucial to early exploration – the world would look very different now if we had been unable to use the starry signposts in the sky to guide ships and open trade routes.

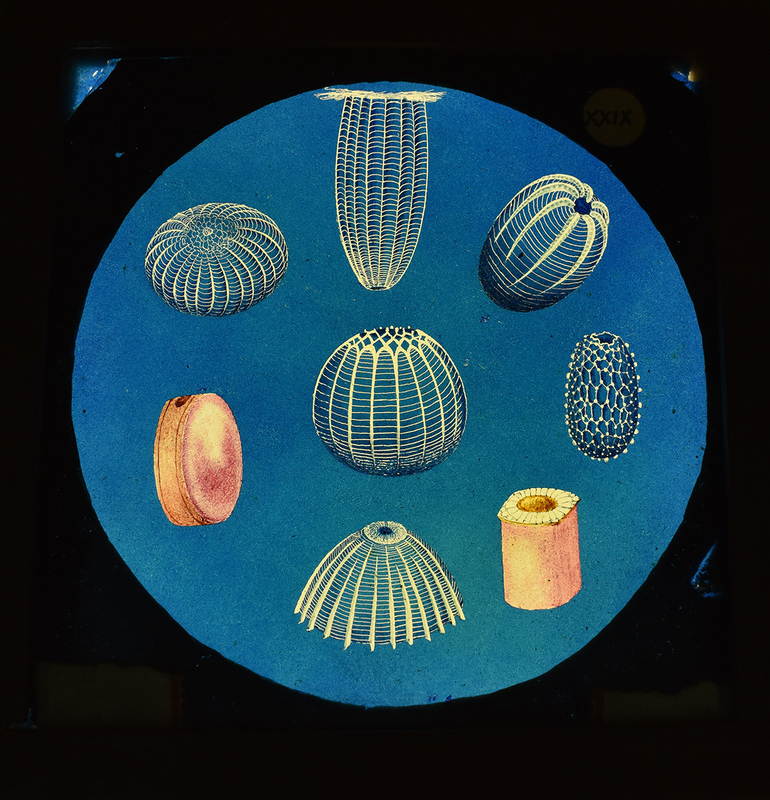

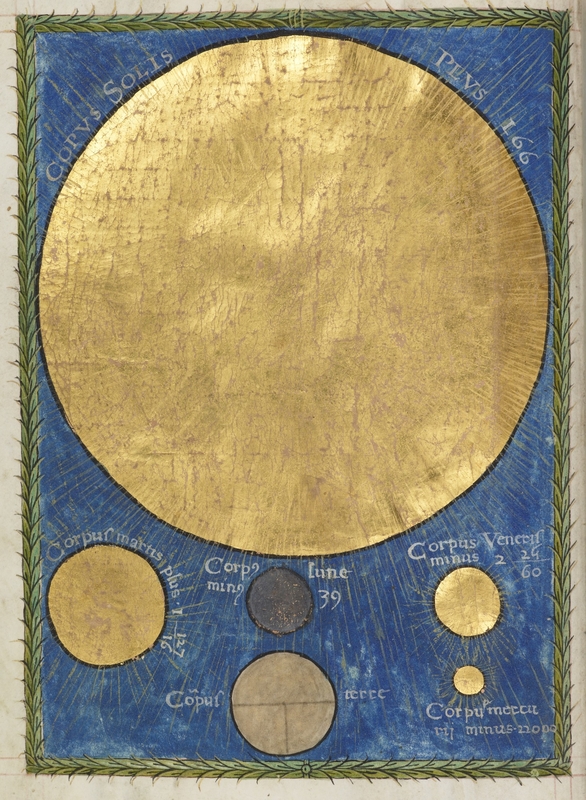

These beautifully crafted tools often blur the borders of art and science, such as the pages of Christianus Prolianus' scientific treatise, Astronomia, produced in Naples around 1478. Covering astronomy, the elements and geometry, the manuscript is richly decorated.

Sun, Moon and Planets

(shelfmark 'Latin MS 53', from 'Astronomia') 1470–1480

Joachinus de Gigantibus (active 1470–1480)

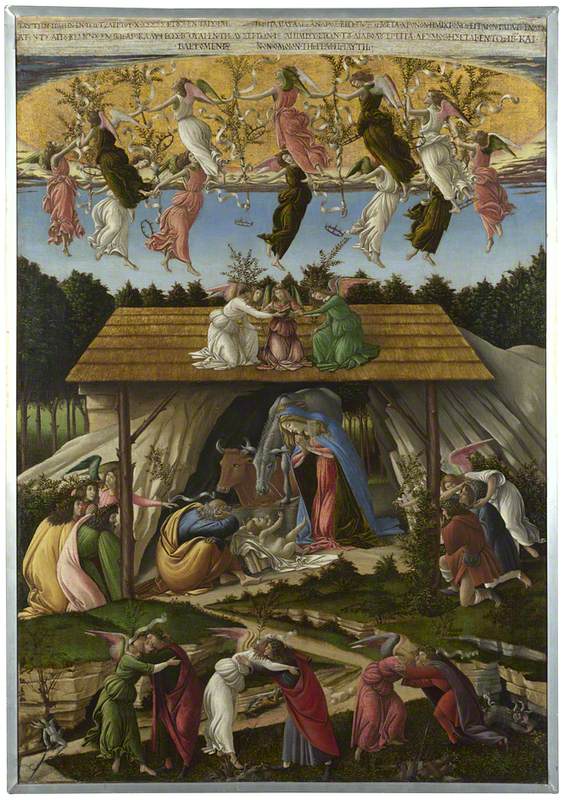

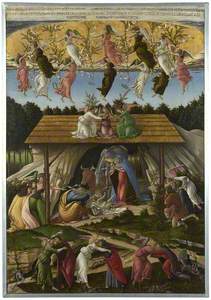

Since God dwelling 'in heaven above' is a central tenet of Christianity, it's unsurprising that early paintings often use the sky as a backdrop to religious events.

The historically lustrous connotations of blue pigment mean the colour is often juxtaposed against gold leaf in Renaissance art, meaning skies are often painted as a swathe of vibrant cerulean (maybe with a golden angel or two) – but night skies are not so common.

We need to look for specific biblical tales set at night – like 'The Agony in the Garden' – to find darker skies in Middle Ages art or find astrological iconography, astrology being an important part of medieval life.

The Agony in the Garden

probably about 1520-39

Benvenuto Tisi da Garofalo (c.1481–1559)

It is not until image-making becomes more accessible that we see the earliest naturalistic depictions of the night.

Credited with being the first artist to represent the night sky accurately, Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610) painted The Flight into Egypt in 1609 – the painting is in the collection of Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

The Flight into Egypt

1609, oil on copper by Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610)

What is unusual about this biblical interpretation is Elsheimer's treatment of the sky as a spectacle rather than a background: the reflection of the glowing moon gives sombre depth to the scene, and the sparkling Milky Way is painted realistically. The artist worked on copper to allow such details.

In art, the Milky Way is usually depicted in the context of the myth – Zeus let infant Heracles (his half-mortal son) feed at the breast of the goddess Hera who, on waking, pushed the infant aside: the resulting milk sprayed out to make the stars.

In the UK, we have another of Elsheimer's night scenes – possibly painted just before his Flight into Egypt. Though this time the night sky is overcast, we can see him start to hone his craft in the details of light peeping through clouds and the distant, glowing fires.

Following on from Elsheimer, in Amsterdam, Aert van der Neer (1603–1677) was known as a master of moonlight and winter ice-skating scenes.

His night landscapes show the moon lighting up the skies so intensely, with intricate cloud cover, that people living in light-polluted cities today might struggle to see such skies as realistic – the small figures going about their nightly business even have shadows in the rich moonlight.

Throughout art history, there have been others known for their treatment of conjuring the night on canvas.

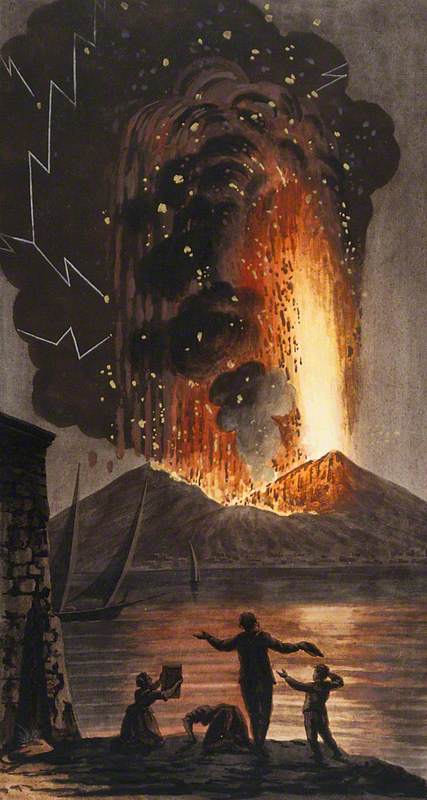

The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius on the Night of 8 August 1779

1779

Pietro Fabris (active c.1740–1804)

Pietro Fabris (active c.1740–1804) was known primarily for his paintings of volcanic activity, the resulting rocks and minerals and the plumes of smoke they emit, having worked closely with the British diplomat and volcano-enthusiast Sir William Hamilton.

Lava Emerging from Mount Vesuvius at Night and Running towards Resina, 11 May 1771

1776

Pietro Fabris (active c.1740–1804)

Mount Vesuvius in Eruption in 1767, from the Mole at Naples

1776

Pietro Fabris (active c.1740–1804)

Firey volcanic activity is best offset against a night sky. Fabris was mainly a scientific observer: his scenes are rather focussed on the contrast of the hot glow of lava or electrical disturbances than what is happening in the sky above. He recorded the eruption of Vesuvius first hand, a view also famously painted by Wright of Derby.

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples

c.1776–80

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) had a brilliant career, especially considering he usually worked outside of the capital. He became a master of tenebrism – the dramatic technique of using a heavy, dark background to contrast light. Wright visited Italy during 1773 and 1775, just missing the eruption of Vesuvius in 1777, yet it's likely he saw some volcanic activity as Vesuius had sputtered out lava for years prior.

Italy's night skies must have been quite a sight to keep Wright interested in painting them for the rest of his life: back in his native Derby, Wright conjured lustrous views of Tuscany or unusual coastal rocks silhouetted against the moonlight.

Grotto in the Gulf of Salerno, Italy, Moonlight

1780–1790

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

Born later than Joseph Wright of Derby, J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) also looked to the sky.

With hundreds of works in UK collections, it's hard to find a version of the sky that has not been painted by Turner, from twilight to dawn, or all around the clock – though where Wright used pitch black for dramatic emphasis in his night scenes, Turner is well known for his riotous, Romantic blends of colour, blending accuracy with an impressionistic style. He was fascinated with clouds and haze, his focus more on earthly horizons than celestial skies.

Turner worked throughout a strange, devastating event that impacted the world's skies. The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 led to 'The Year without Summer' – the ashy haze in the atmosphere impacted temperatures and food production. It must have felt like a miserable, eternal twilight, albeit with spooky blood-red sunsets. Compare Turner's clear view of Lake Avernus to his apocalyptic Decline of the Carthaginian Empire, with broken detritus and anguished figures.

The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire ...

exhibited 1817

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Landscape paintings in the early seventeenth century show an amazing record of the eruption's impact, not just limited to Turner: the darkening of the skies appears to shift many artists' focus from carefree breeziness to dark and foreboding atmospheres, with people at the mercy of nature.

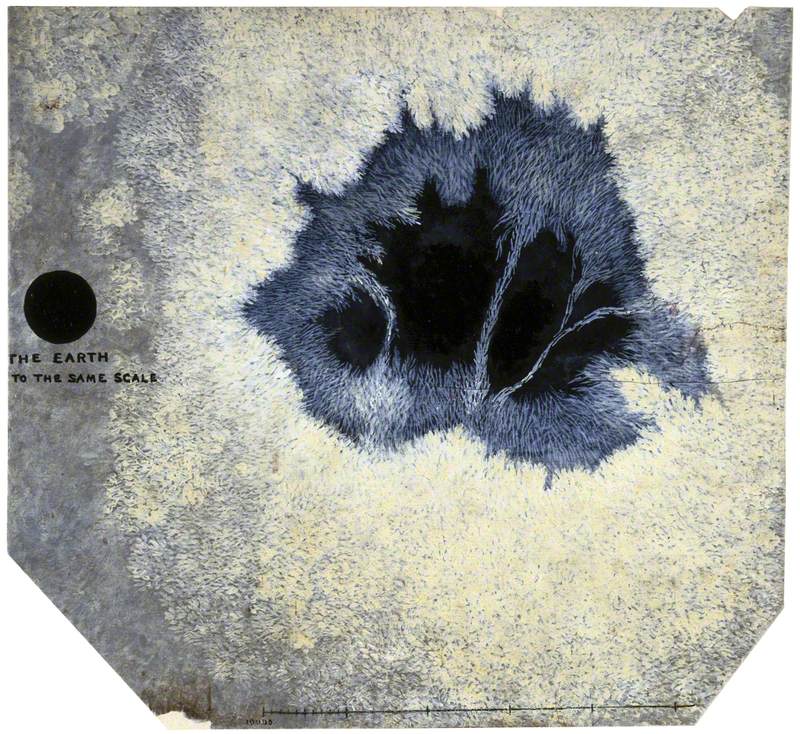

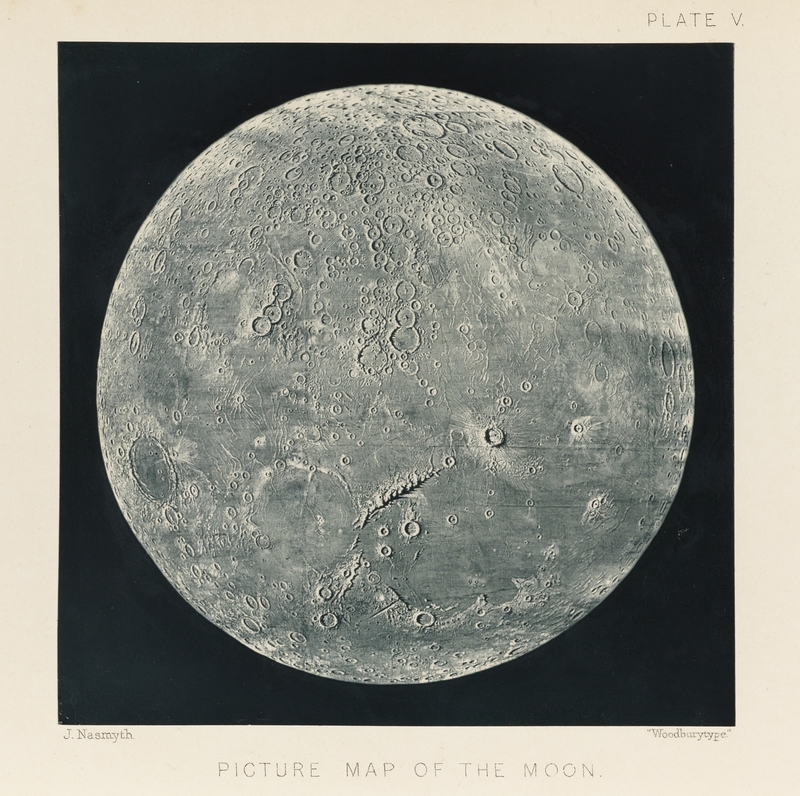

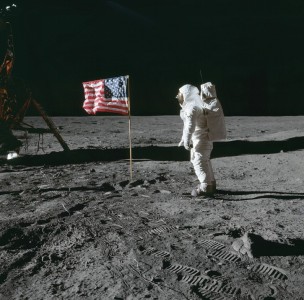

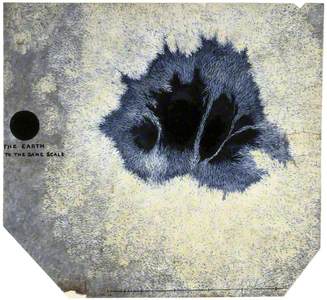

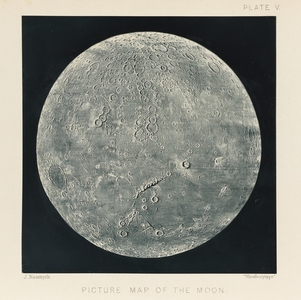

After the volcanic haze had cleared away, people could peer uncluttered into space once more, at comets and meteors, planets and stars. Along with painting details of solar flares, engineer and astronomer James Nasmyth (1808–1890) made a wonderfully detailed Woodburytype – a light-sensitive gelatin process – of the moon.

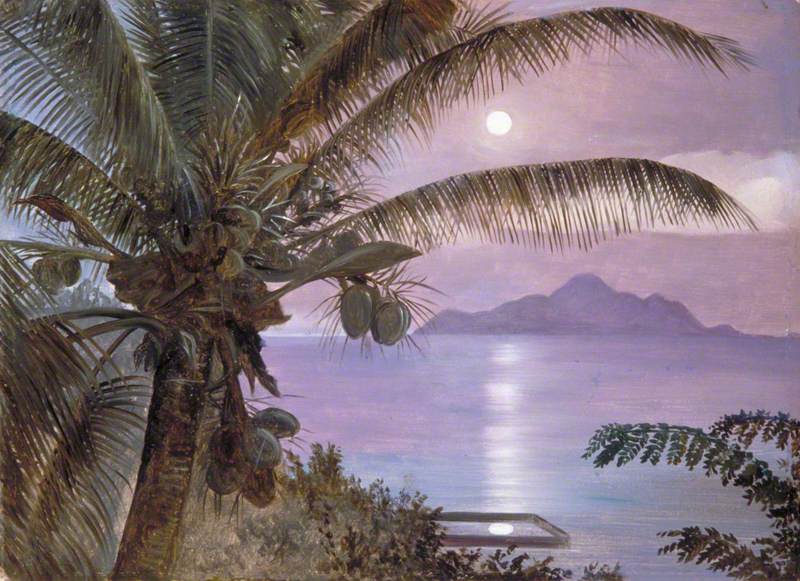

The moon is represented in many hundreds of artworks on Art UK, and a great many of these are made by members of the Pether family.

Though father Abraham (1756–1812) was a prolific worker and polymath, the large family often struggled to get by. Son Sebastian (1790–1844) painted gothic night landscapes, while Henry (1800–1880) focussed on moonlit cityscapes.

A Ruined Gothic Church beside a River by Moonlight

1841

Sebastian Pether (1790–1844)

It can be argued that no one painted moonlight with as much luminosity as self-taught, Leeds-born John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893), who quit his job as a railway clerk to become a painter.

His distinctive, acid-green night skies act as the perfect backdrop to intricate silhouettes of gaslit buildings, ships and bare winter branches. A fan of photography, Grimshaw used a camera obscura to aid his lines of perspective.

Grimshaw's contemporary, the more famous James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), said, 'I considered myself the inventor of nocturnes until I saw Grimmy's moonlit pictures.'

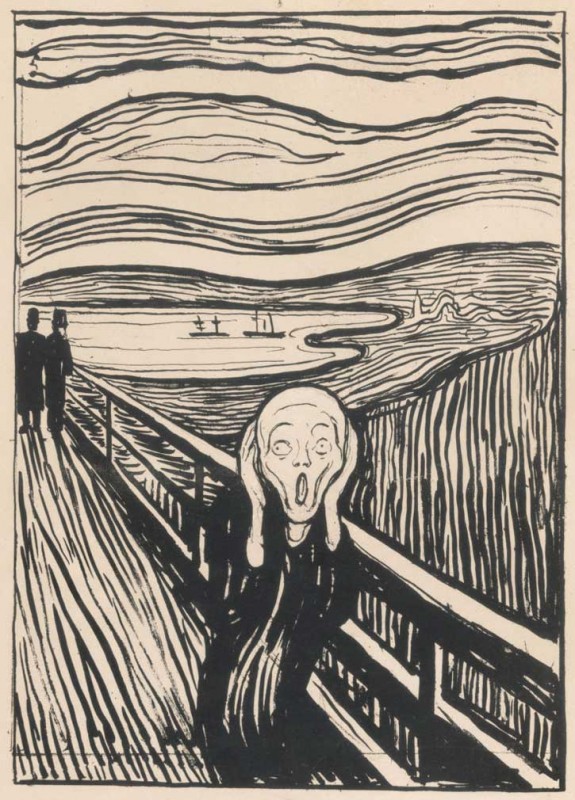

Softer and more impressionistic than Grimshaw's, Whistler's views are shrouded in mist. They imply a night sky that harbours secrets, their stillness lending an air of mystery or melancholy. While the above 1871 work was the first of his 'nocturnes', his 1875 painting of a firework display caused a commotion: John Ruskin accused the piece of being lazy, akin to 'flinging a pot of paint in the public's face' (his comments became central to a libel case that financially devastated Whistler).

From a twenty-first-century perspective, Whistler's moody and atmospheric nocturnes seem almost contemporary and we can see their influence throughout later centuries.

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge

c.1872–5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

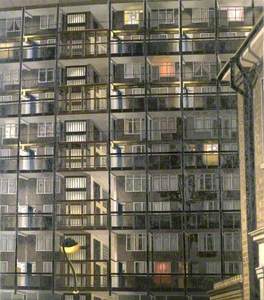

With the ubiquitousness of electric lighting in the modern era, more recent night scenes tend to adopt the twinkling lights of cities as their bright focal points over the moon and stars. Even the French Impressionist Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), who often looked to nature, set his rare nocturnal painting in an urban area.

While electric lighting can promise warm shelter or the liveliness of a city, industrialisation can also be interpreted to alienate us from nature. The dramatic, backlit plumes of smoke in The Steelworks, Cardiff at Night demonstrate typical nineteenth-century concern – and fascination – with urban sprawl.

The Steelworks, Cardiff at Night

1893–1897

Lionel Walden (1861–1933)

Urban populations had another reason to look into the sky with trepidation during wartime – perversely beautiful paintings of the Blitz show searchlights and artillery fire lighting up the sky like a firework display.

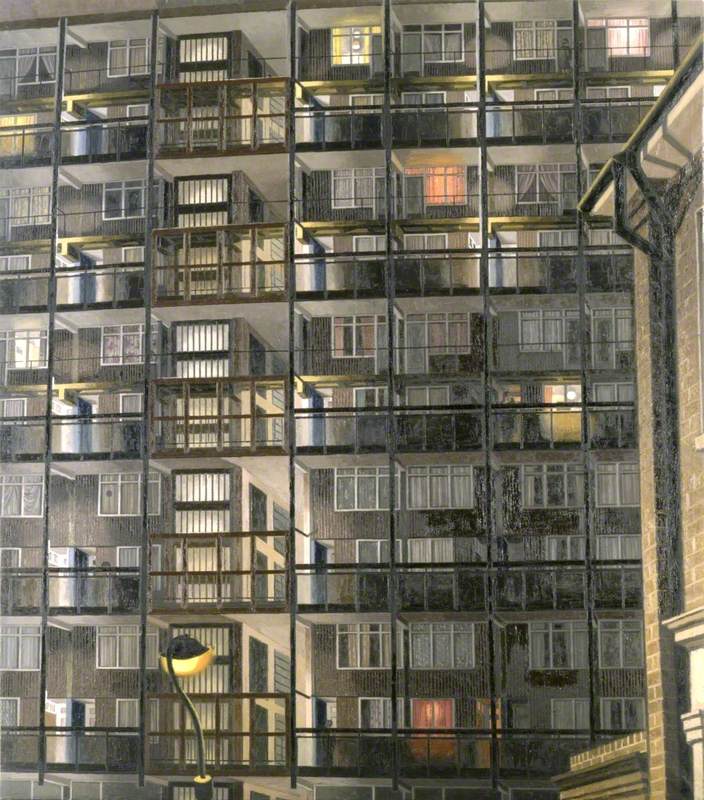

Today, many city-dwellers find it difficult to get a clear view of the night sky: it is either blocked by buildings or haze lit by streetlights below.

However, we are arguably allowed more nocturnal freedom than our ancestors – we travel about at night as we do in the day, for many different reasons. Aptly, modern scenes of the night are diverse, in their colours, themes or interpretive possibilities.

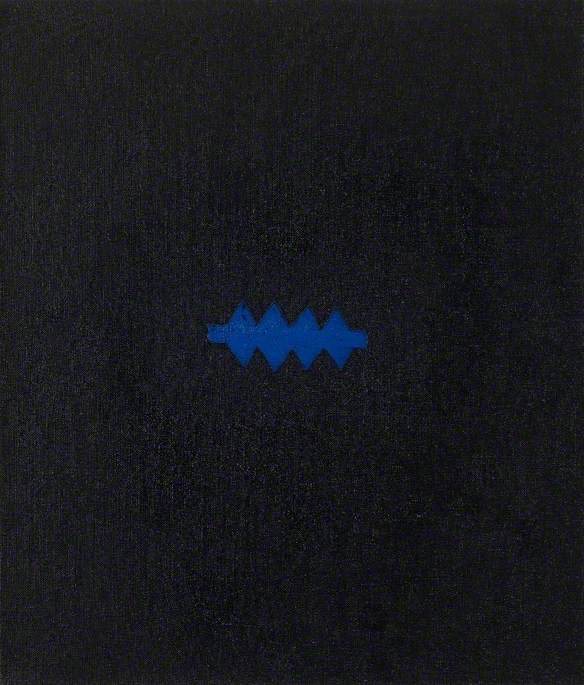

From the harsh lights of motorway vehicles cutting into the dark to abstract experiments with colour inspired by night views, art represents our varied attitudes to the night. The moon is a symbol with myriad meanings: feminine power, melancholy, madness – or as something that connects us with ancient traditions.

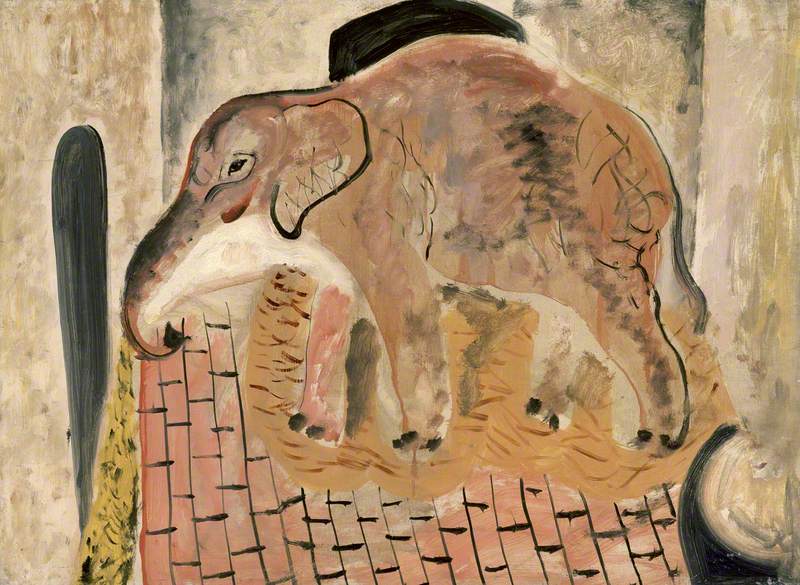

Animal with Moon in a Moonlit Landscape

2001–2006

Lorna Graves (1947–2006)

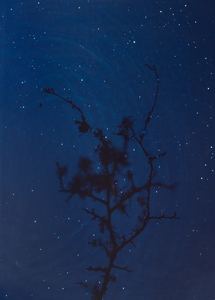

Among these diversified contemporary takes is still a common thread: of awed wonder at the beauty of the night sky. Susan Derges (b.1955) is a specialist in camera-less photography – her experiments tap into alchemical magic. In Starfield – Blackthorn, the ambient light of the moon is captured by exposing images directly onto light-sensitive paper.

Situated within Northumberland's International Dark Sky Park is Kielder, home to Kielder Observatory and one of the largest sculpture parks in the UK.

Unique to Kielder Water & Forest Park is its blend of art and nature – architectural constructions such as The Warm Room provide a shelter specifically designed to foster a mindful connection with nature through the medium of stargazing.

While art can simulate the beauty of the night sky, these contemporary works imply there is nothing like the real thing: gazing up at an uninterrupted view of the cosmos soothes the soul and inspires a deep connection to nature.

Jade King, Lead Editor at Art UK

Explore the Art UK Shop's 'night sky' theme for prints of moonlit landscapes and starry skies