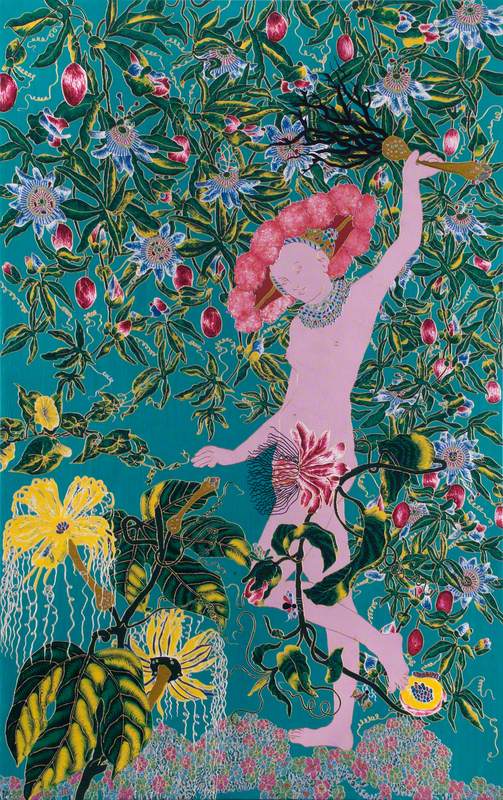

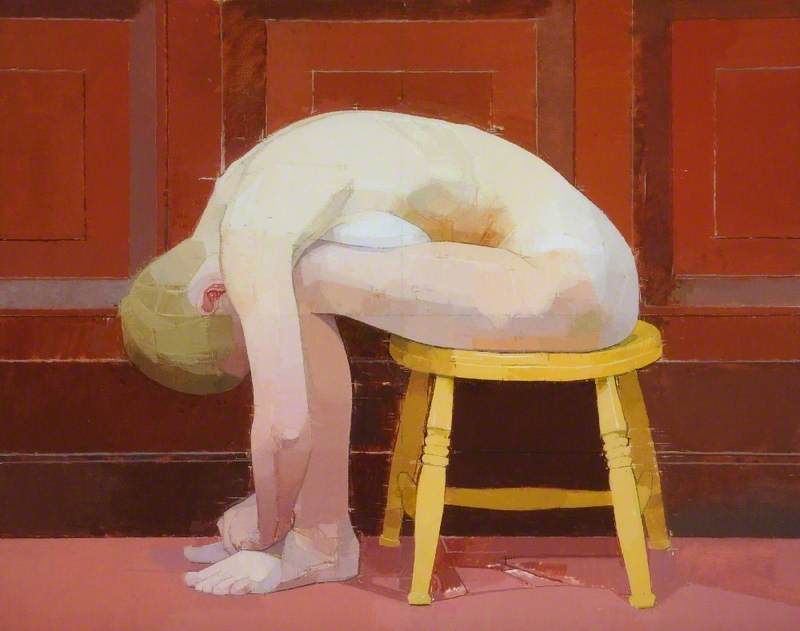

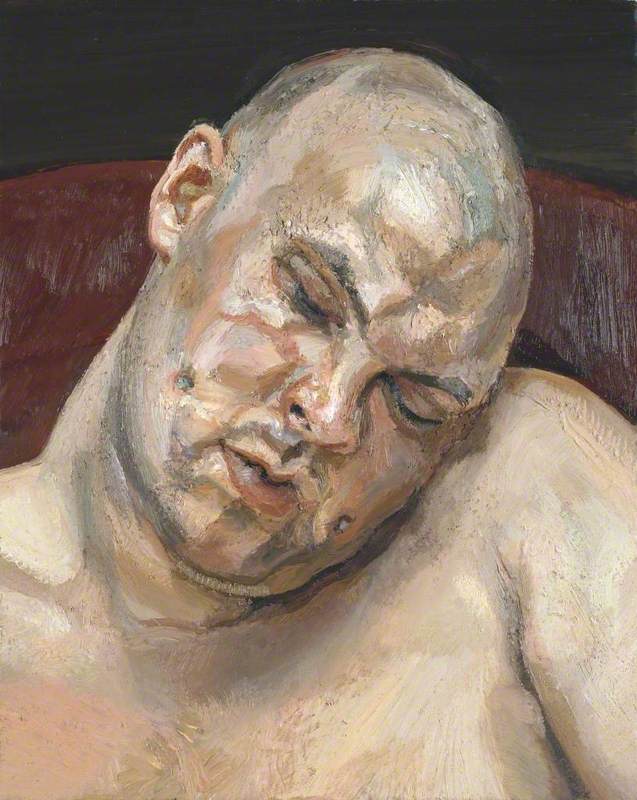

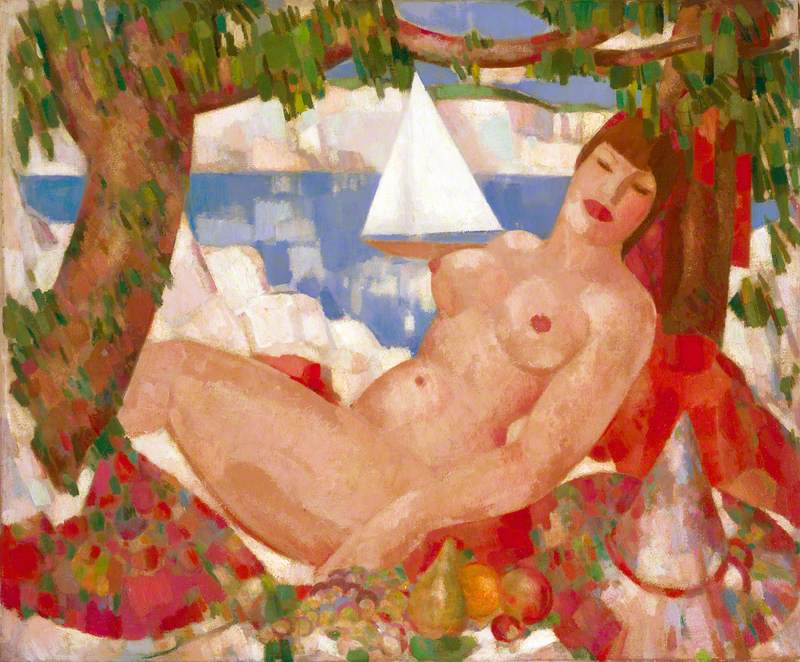

A Venus, in painting and sculpture, may be one of the most popular subjects in art. A nude, reclining woman as the subject of painting was often titled 'Venus', such as Titian's Venus of Urbino (here seen in a copy by William Etty).

Venus of Urbino

(after Titian) 1823

William Etty (1787–1849)

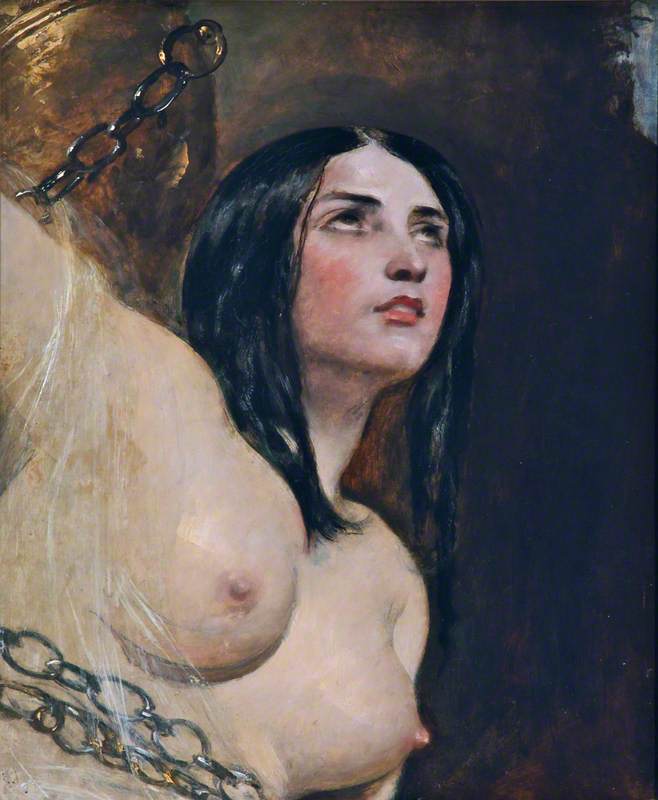

In his seminal 1956 work The Nude, art historian Kenneth Clark identified a significant thematic divide between the innocent Venus, blithely naked and unaware of an audience, and the coquettish Venus, who covers herself because she knows she has something to hide.

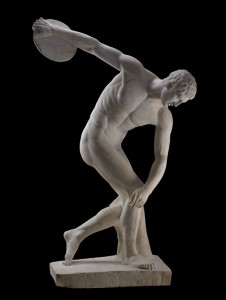

The concept of the Venus extends back to her counterpart in Greek myth, Aphrodite. The Knidian Aphrodite, argues Clark, steps into her bath, unconcernedly exposed, whereas the Capitoline Aphrodite (here shown in a copy at Knole, known as the Venus de' Medici), half-covered: 'herself self-conscious, is the product of self-conscious art'.

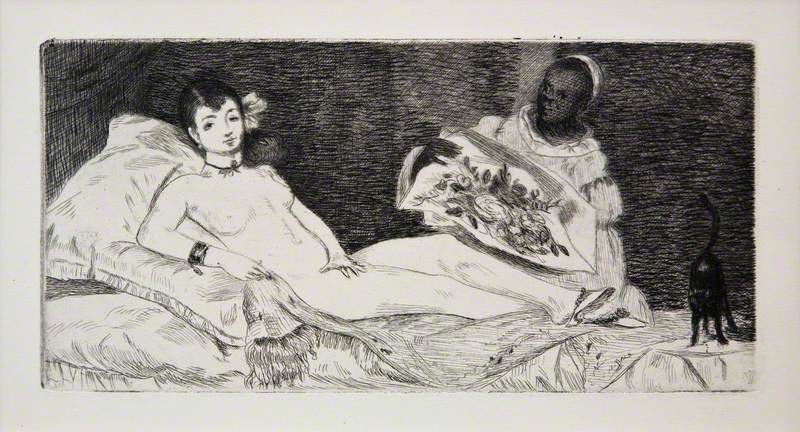

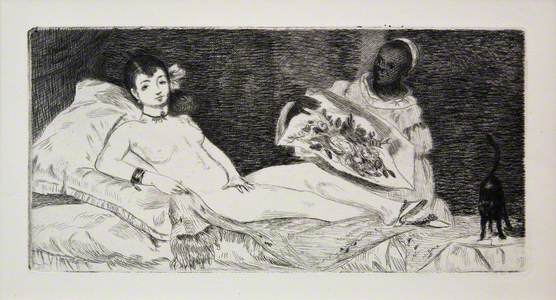

Edouard Manet was a painter whose self-conscious subjects brought him much acclaim. Perhaps his most famous painting is Olympia, staged after the style of the Venus of Urbino. But the model was not an abstract representation of a goddess, or even an 'odalisque' – a woman from a harem, who served a similar purpose in painting as that of a goddess: to be both nude and anonymous. Instead, Olympia was received, and scorned, by critics and public as something like a nude portrait – a recognisable individual, Victorine Meurent, stares out boldly from the canvas.

Clark argues that Manet's Olympia (seen here as a print made by the artist) caused a scandal because, 'to place on a naked body a head with so much individual character is to jeopardise the whole premise of the nude'.

Meurent was a model, music tutor, and painter. As V. R. Main said in a 2008 article in The Guardian: 'By 1875, she had returned to Paris and was attending evening classes at the Académie Julian. Her self portrait was shown at the Salon in 1876, and after that her work appeared there in 1879, 1885 and 1904. In 1903 she was elected a member of the Société des Artistes Français'. Meurent is probably the model Manet depicted in the most diverse range of roles. In a 2013 exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, Meurent is described as the subject of a 'straight portrait' (Victorine Meurent, c.1862), as a bold nude (Dejeuner sur L’herbe, c.1863–1868), as the controversial Olympia (c.1863), and as the beguiling young woman in The Railway (1873).

Déjeuner sur l'herbe

c.1863–1868

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

In Street Singer (c.1862) Meurent poses as woman on the fringes of society, provocatively eating ripe cherries as she holds a guitar. This latter painting, showing a hungry girl with dark shadows around her eyes, could be interpreted as tragically prescient – Meurent was often cited as having fallen into poverty and alcoholism, now a strongly contested point. Meurent did struggle with poverty. She wrote to Manet's widow in 1888, six years after the painter died, when the model would have been 44:

'No doubt you know that I posed for a great many of his paintings, notably for Olympia, his masterpiece. M. Manet took a lot of interest in me and often said that if he sold his paintings he would reserve some reward for me… Certainly I had decided never to bother you and remind you of that promise, but misfortune has befallen me: I can no longer model, I have to take care of my old mother all alone… and on top of all this I had an accident and injured my right hand… it is this desperate situation, Madame, which prompts me to remind you of M. Manet’s kind promise.' (i)

The appeal for funds is often cited in books of art history, but the next sentence always moves on to something else. Did Mme Manet respond? Why don't historians acknowledge whether or not there was a reply? Because, one is tempted to conclude, Victorine only matters in light of Manet, not for herself – turning her into a Venus after all.

Kelley Swain, author of The Naked Muse (Valley Press)

(i) Alan Krell, Manet, Thames & Hudson, pp.49–50