10 Downing Street: one of the most famous addresses, with one of the most famous front doors, in the world. Official residence of the British Prime Minister since 1735, it has been lived in by Disraeli and David Lloyd George, Churchill, Thatcher, Blair, and Larry the cat; it has hosted everyone from Barack Obama to Noel Gallagher.

President Barack Obama is welcomed to 10 Downing Street in London by British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, April 1, 2009.

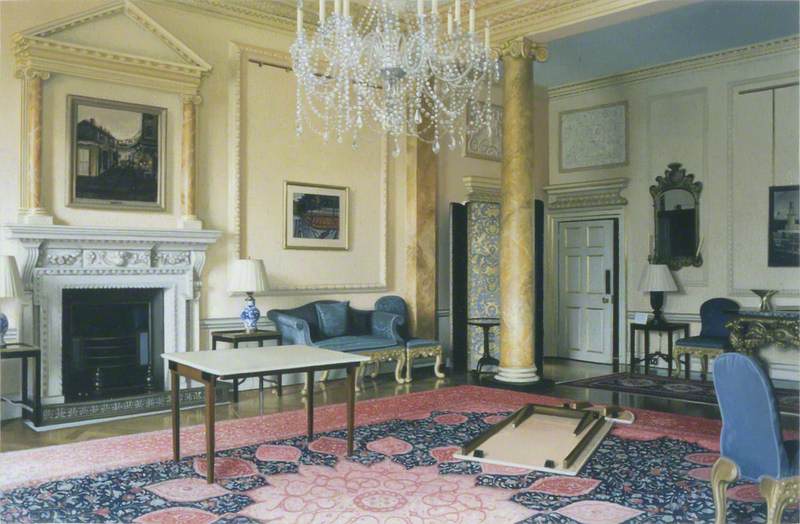

One of the lesser-talked about features of Downing Street is the art that adorns its walls; yet those who work in the building come and go every day under the watchful eye of some of Britain’s finest artworks.

This is largely thanks to over a hundred years of curation by the Government Art Collection (GAC), established at the end of the nineteenth century. Few people have regular access to see its art in person – hanging as it does in government buildings and ambassadorial residences across the globe – but it's not kept secret, either. You can see all of its paintings on Art UK, and search the wider collection on the GAC website.

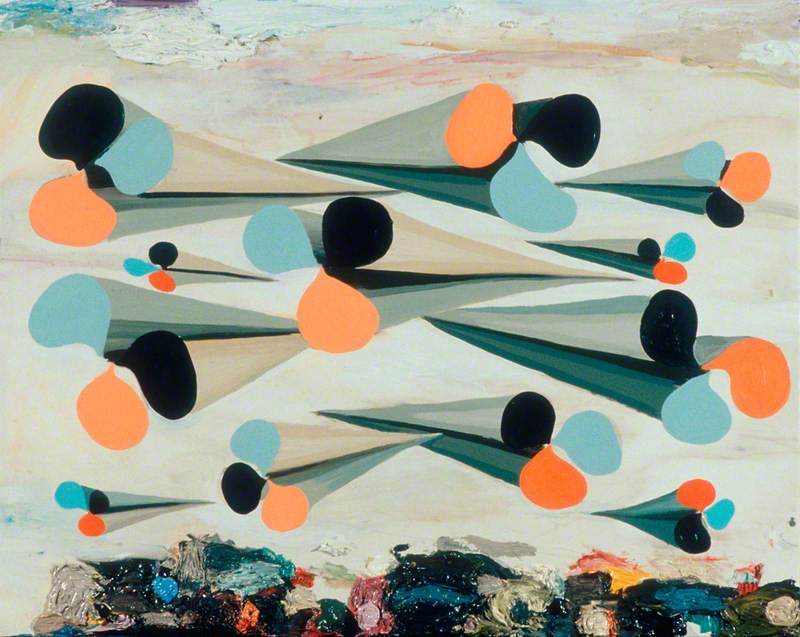

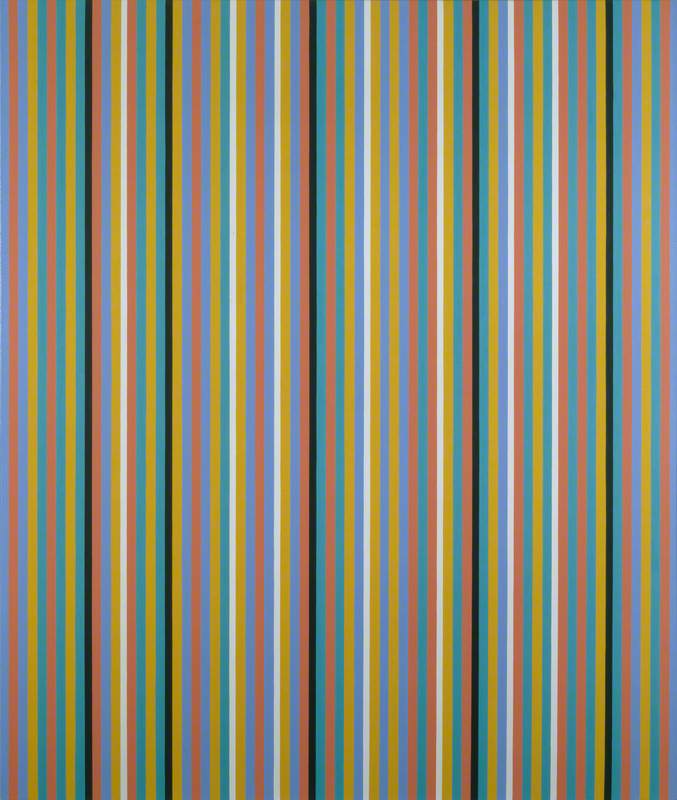

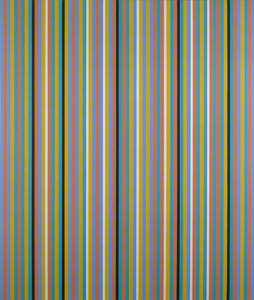

The GAC’s works date from the sixteenth century to the present day, designed to show off the best of British art across the years. Around half of the works on display in Downing Street come from the GAC and the other half are loans from British galleries: so if you were to visit you’d be just as likely to stumble across this abstract Phillip Allen piece (currently on display) as you are a portrait by Godfrey Kneller.

Art can be a refuge, and take the mind to different places: or at the very least provide a temporary distraction from the machinations of diplomacy.

With this carefully curated mix of the traditional, the contemporary and selected portraits, Downing Street represents a kind of conflation of the National Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Modern.

Through the keyhole: discovering a Prime Minister’s tastes

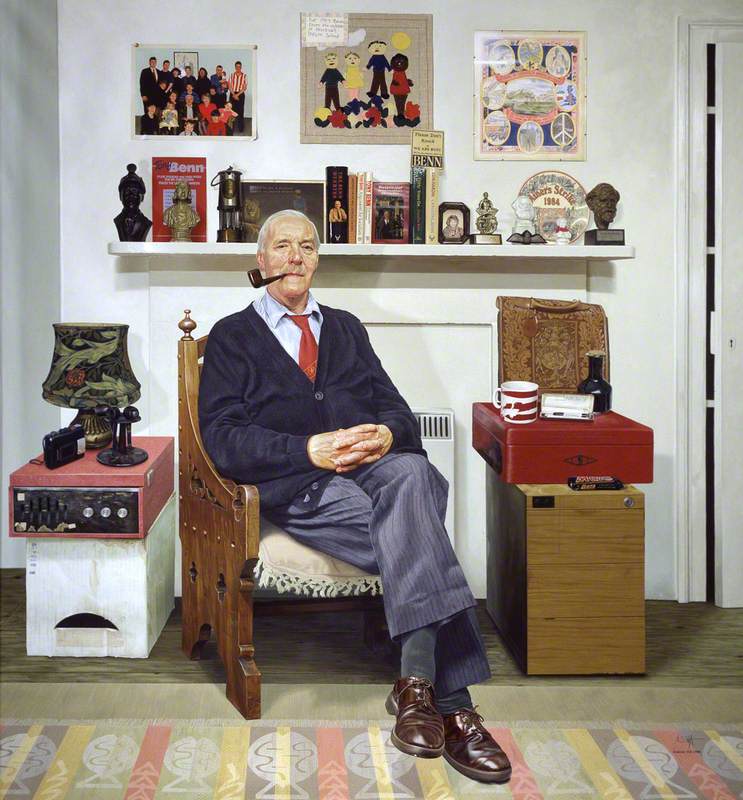

When a new Prime Minister moves into Number 10, they’re able to choose some of the art to adorn their walls – and their choices are often revealing.

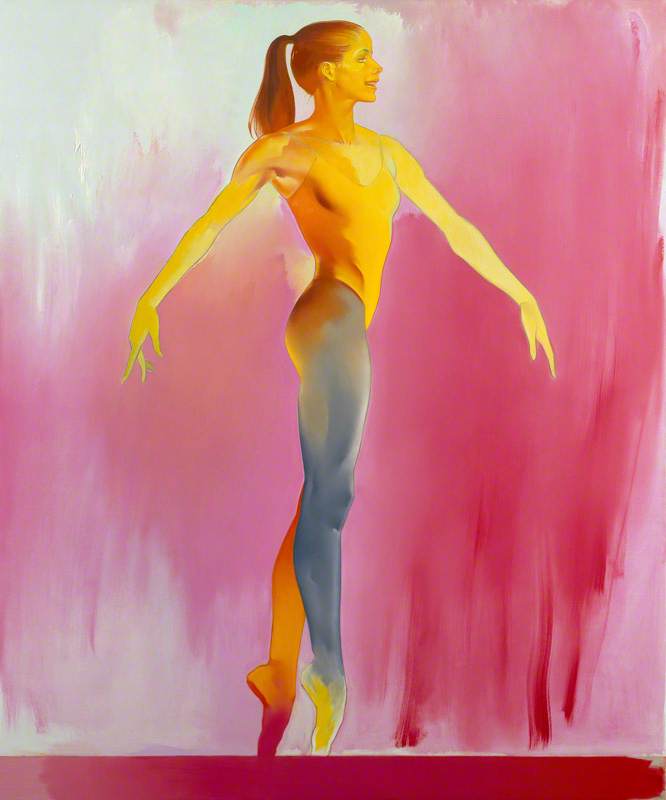

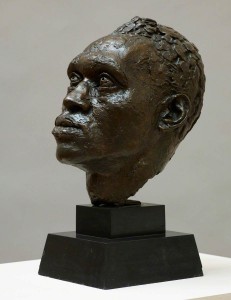

When the Blairs first took up residence, Tony and Cherie accepted the offer of a number of loans from the National Portrait Gallery. And so, in the Pillared Room, they traded Edward Pellew for Darcey Bussell, and Sir William Fawcett for Sir Dirk Bogarde; William Pitt the Younger had to (temporarily) make way for Kazuo Ishiguro. The contemporary portraits went hand-in-hand with the image the Blairs were cultivating: fresh-faced and forward looking. Guests could mill around the room enjoying one of their drinks receptions, looked down on not by musty, long-dead figures but by contemporary dancers and Booker prize-winning authors.

The Blairs are not the only ones to show a taste for the modern. David Cameron invited Tracey Emin to design a piece specifically to hang in Downing Street: More Passion was the result, a short, simple rendering of her famous neon signs. On the GAC’s website, it describes that the work was intended to be a juxtaposition to the ‘functional’ aspect of many of Downing Street’s rooms: that Emin wanted the contrast to make those passing through stop and reflect.

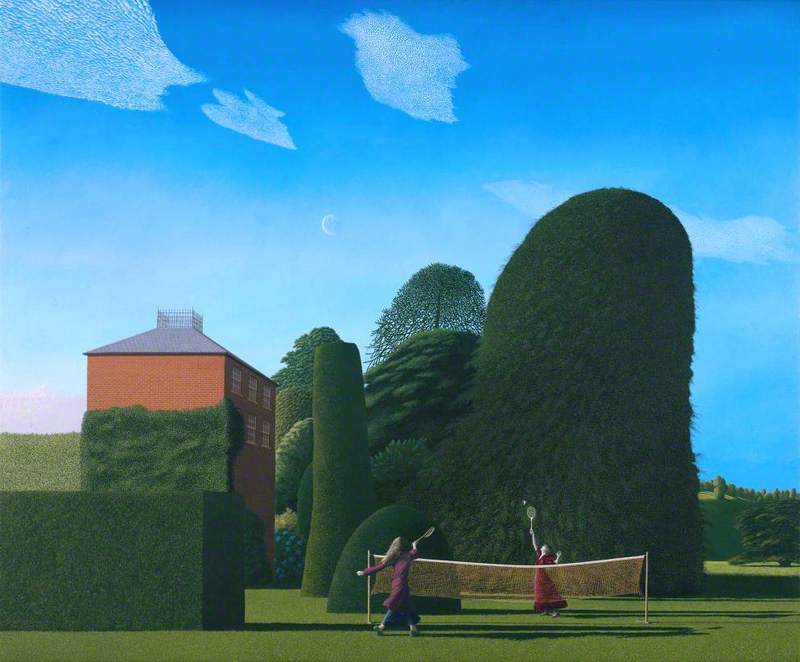

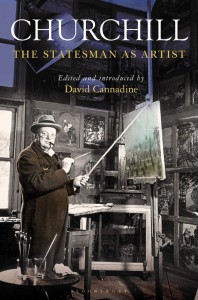

At the more traditional end of the scale, Margaret Thatcher reportedly enjoyed landscapes by Constable and Turner. On modern art in Downing Street, she said ‘I think if you have what I call the geometric ones – just pure different squares, triangles and heaven knows what put together – I don't think they go with the general background’. While her successor John Major apparently liked the works of David Hockney, he also brought his idealised vision of England to life with paintings like a portrait of the cricketer W. G. Grace and David Inshaw's The Badminton Game (both removed by the Blairs).

Gordon Brown also showed himself to be something of a traditionalist, choosing a series of landscapes to adorn the walls for his tenure: a decision scathingly referred to as 'the bland leading the blind'.

Art is political, and paintings are diplomats

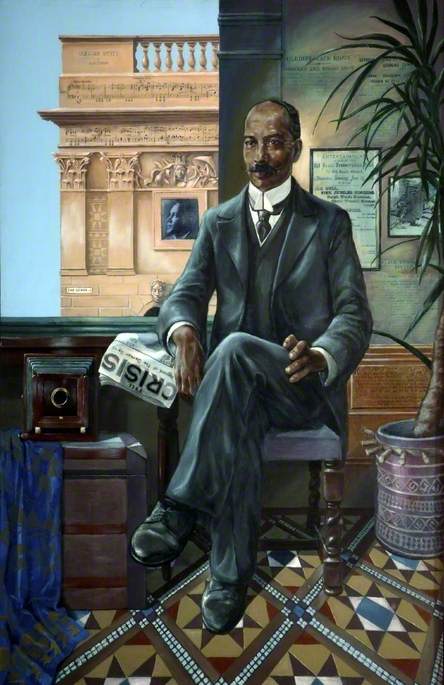

The art on the walls in Downing Street is partly a tool of soft power: a showcase of British history, creativity and ingenuity to the world leaders who arrive in London. However, through the GAC, art also travels and represents the UK abroad, living in embassies, ambassadorial residences and the offices of diplomats.

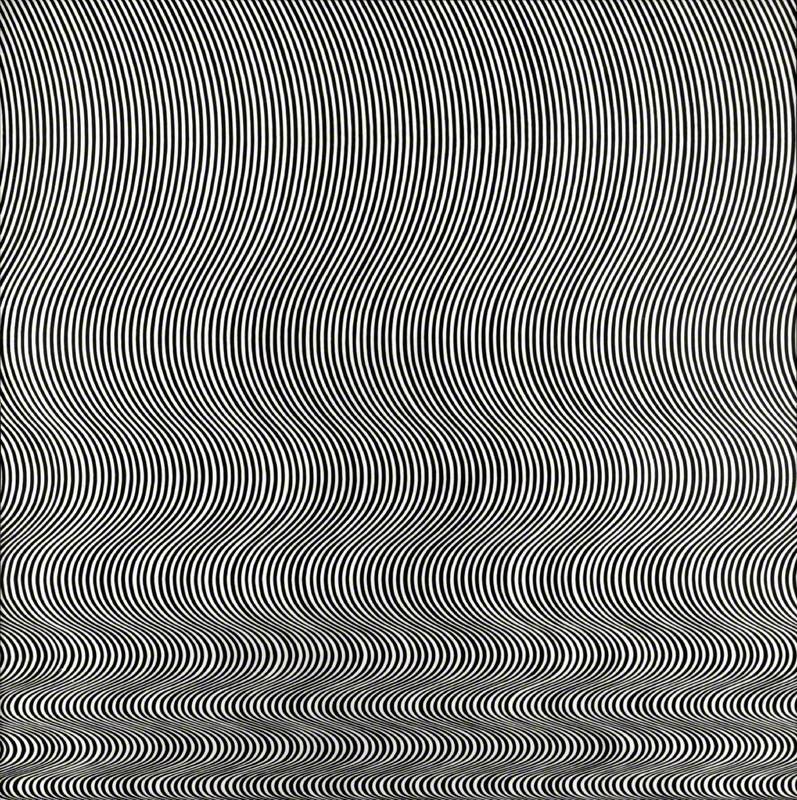

The art is carefully matched to its home, taking into account both practical considerations – the art must be robust enough to withstand foreign climates – and more aesthetic ones. If you were to stroll into the Ambassador’s Residence in Cairo, you would come across Bridget Riley’s Reflection. The piece was inspired by the colours Riley saw in the wall paintings of the tombs in Upper Egypt, so the GAC saw it fitting to send the painting to Cairo.

While abroad, these artworks play a diplomatic role. They help to project a certain image of Britain: Karen Pierce, a former UK Deputy Representative to the UN, believed that the art on display in the residence in New York helped to sweep away presumptions about Britain as a stuffy, colonial country: ‘... they (other countries) would see this fantastic modern art, in all its colour and all its glory, and it would lend credence to the image that we were trying to project… when you saw this art, which ranged from Andy Warhol to Peter Blake to Joe Tilson, you really got a sense that it was a different sort of country from the one you expected, and that would help us work together’.

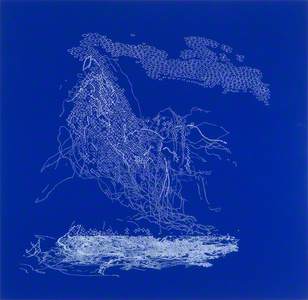

Art can also be a refuge, and take the mind to different places: or at the very least provide a temporary distraction from the machinations of diplomacy. Sir John Sawers, a former British diplomat, chose Claude Heath’s bold piece Ben Nevis on Blue to hang within his office, and recalls a negotiation in Iran that he chaired while sitting under the painting:

‘When the going got tough between Americans, Europeans, Russians and Chinese, we took a break for tea and reflected on the artwork’, he said. ‘Agreement was reached an hour later’.

Of course, displaying works of art in almost every capital city in the world comes with risks. A 2006 Freedom of Information request revealed that 42 artworks had vanished over the previous decade, and in 2011, when the British embassy in Libya suffered an attack, 13 works of art were taken. Now, only digital records exist of those lost paintings, which include an 1840 portrait of William Stratton and Philip Reinagle’s Harrier Killing a Bittern.

As with all of the art on Art UK, these works, while used by government, belong to us all: so go on and explore the works in the Government Art Collection, and imagine what you’d pick if you inherited the office, and home, of Downing Street. For most of its history, this is art that would once have been truly inaccessible: the digital age has given us the opportunity to take a closer look at it.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer