If you've never discovered Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast trilogy before, this might be the perfect season for it. As the nights are drawing in, the year moving to a close with the announcement of a second lockdown, and the weight of traditions gathering pace towards Christmas, where better to spend your time than in the world of his Gothic literature?

Mervyn Peake (1911–1968) is best known for his writing, but he was also a prolific artist and illustrator (13 of his artworks can be viewed on Art UK).

Born in Kuling, China into a medical missionary family, Peake grew up in close proximity to fantastic castles that formed some inspiration for the monolithic enormity of Gormenghast. The young family returned to Britain over the winter of 1922–1923 on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and Peake was sent away to school. He left young, before taking his final exams, to study briefly at Croydon College of Art, then went on to the Royal Academy Schools.

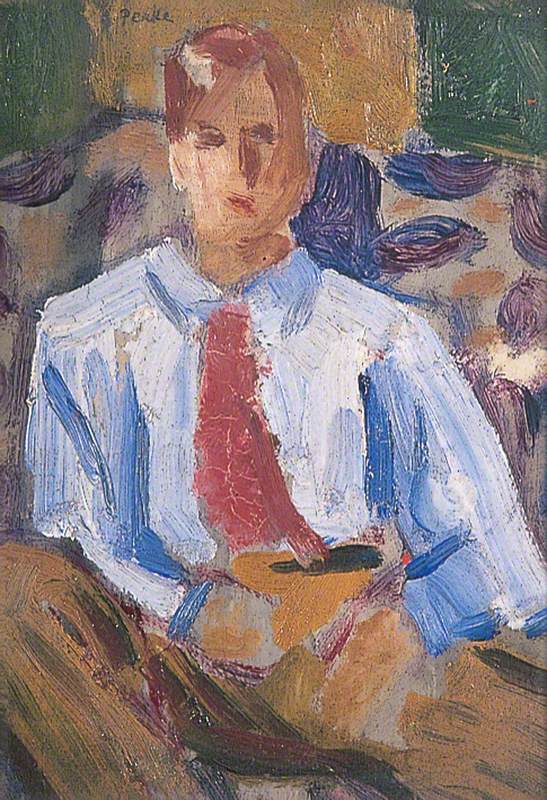

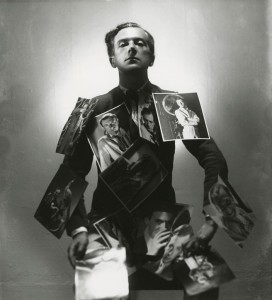

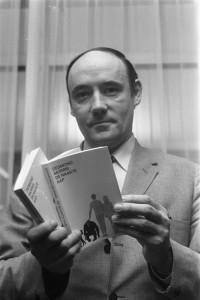

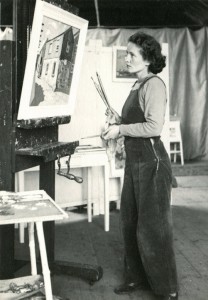

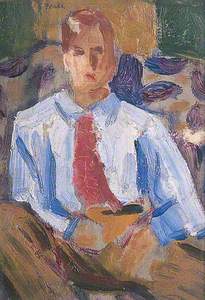

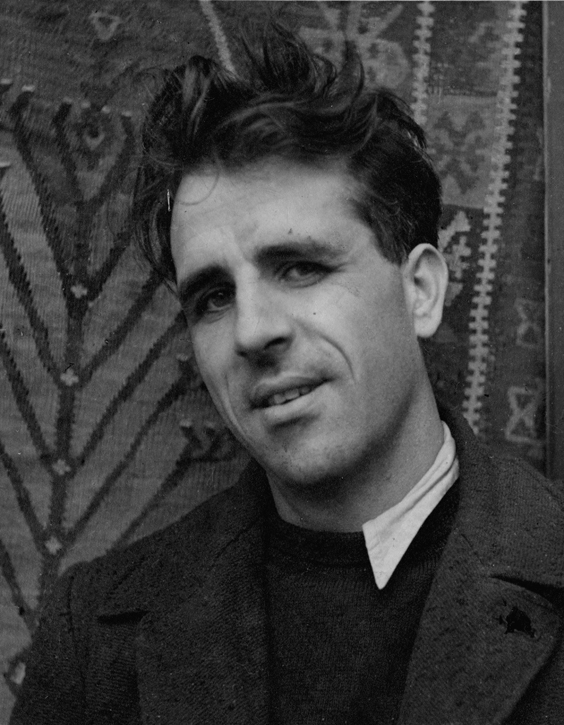

Mervyn Peake

1930s, photograph by unknown artist

By this time he had already published various stories, his first at the age of ten. He carried on writing throughout his studies, including a long poem in the style of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (which Peake later illustrated).

In the middle of his five-year diploma at the Royal Academy, he travelled with his friend 'Goatie' to the channel island of Sark, a significant introduction to a tiny world that he loved and later came to inhabit.

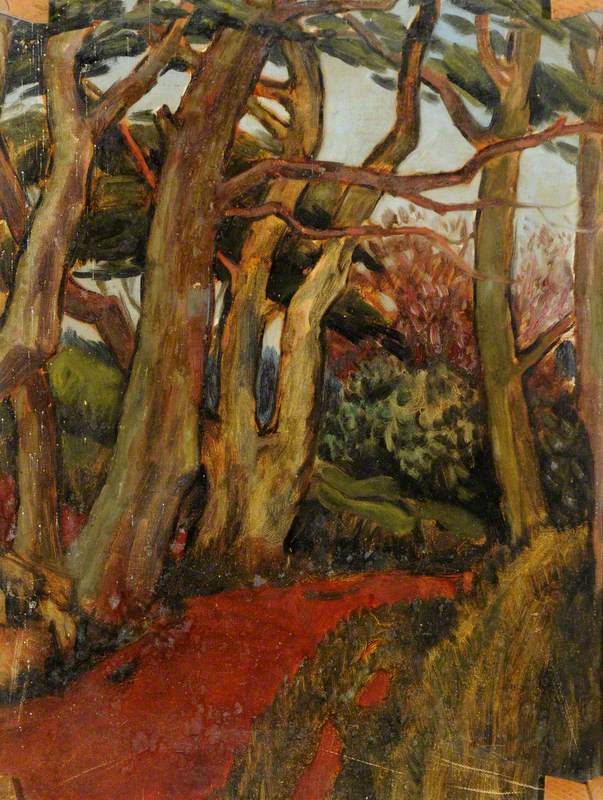

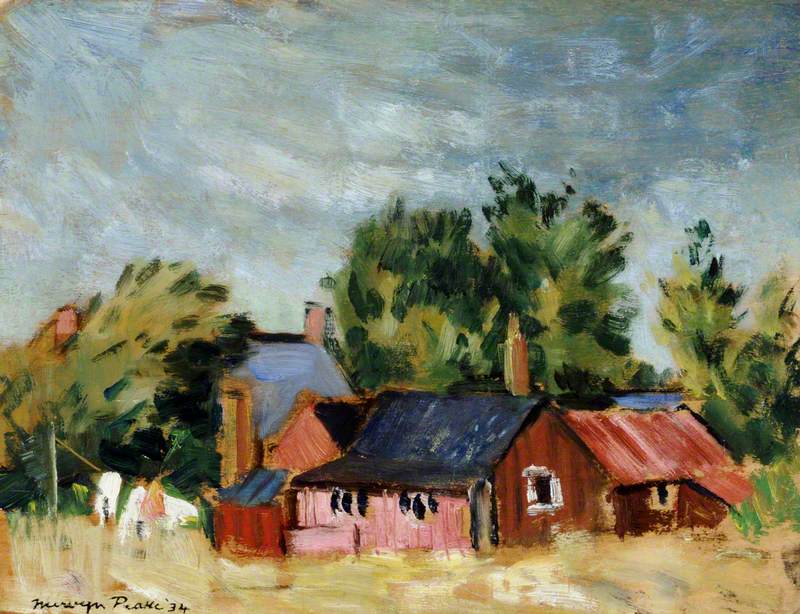

On the remote island, Peake found artistic inspiration, creating two landscape paintings in 1934, which are now housed in the collection of Guernsey Museums and Galleries.

Another of Peake's friends, his former teacher, Eric Drake, had dreams of forming an artists' community and establishing a gallery on the island. Peake's fascination with the island of Sark was so great that his frequent visits caused him to miss most of his classes and subsequently fail his exams in 1933, forcing him to leave the Royal Academy. In a piratical mood (he even had an earring for a while), Peake wrote and illustrated stories for his ferocious picture book Mr (later Captain) Slaughterboard Drops Anchor (c.1936–1938).

The fabulous Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor by #MervynPeake published in 1945 #illustration #pirates pic.twitter.com/QzDqSwQ65G

— Stephen Foster (@fostersbookshop) August 2, 2016

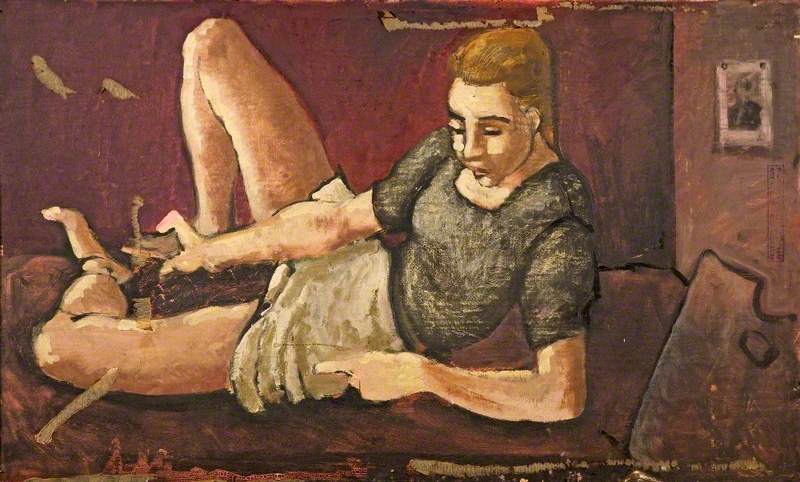

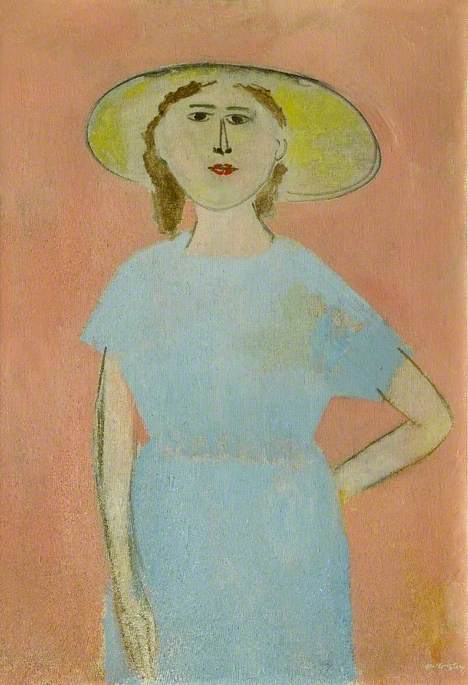

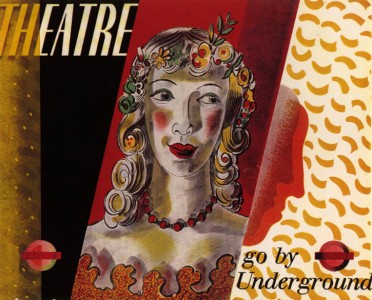

Returning to London, Peake became the set and costume designer for a production of The Insect Play. In 1936, his life changed forever as he met the woman who would later become his wife and the subject of so much of his art, Maeve Gilmore (1918–1983).

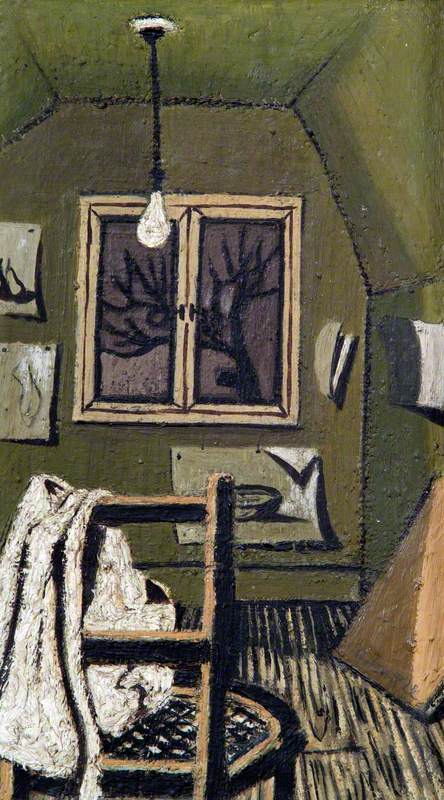

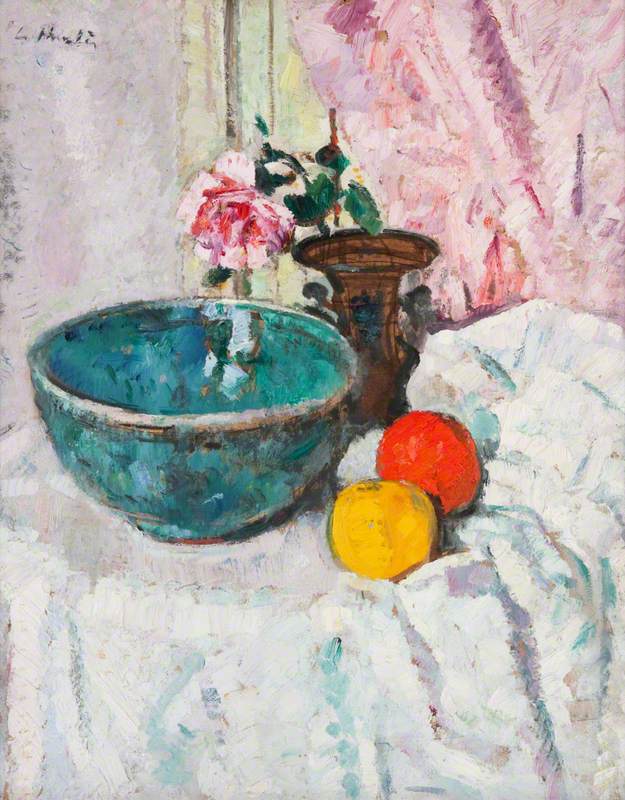

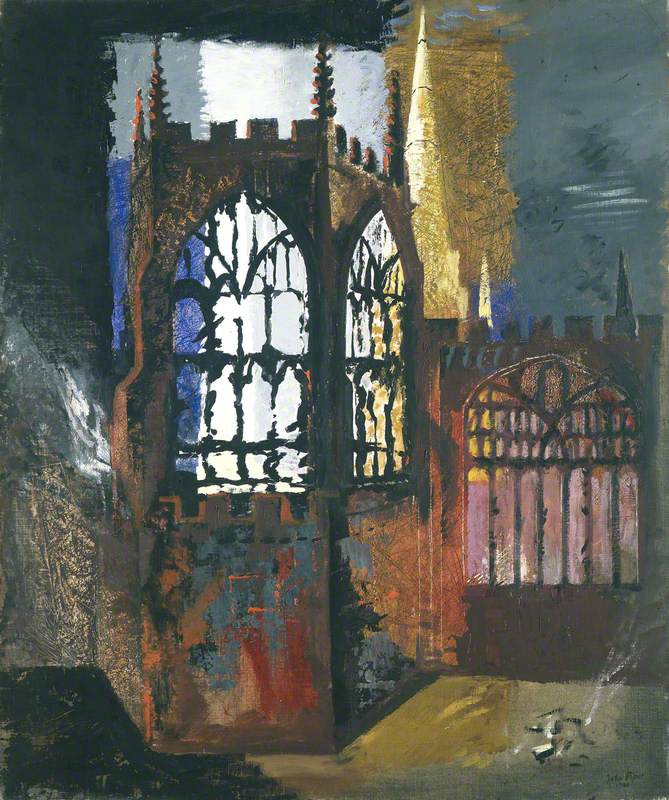

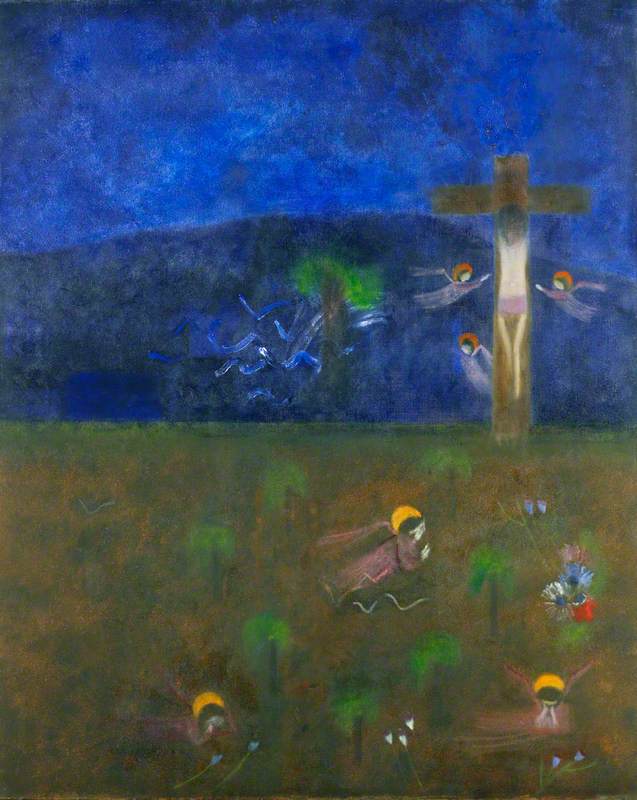

Gilmore was a talented artist in her own right. Two of her paintings are held in the UCLH Arts Store, and much of her works contrast vibrant colour with rich, dark greys, greens, and blacks. This painting that she completed of the attic may be the room in which she painted in the 1950s in suburban Wallington. The married couple moved around before settling in Lower Warningcamp, Sussex, in 1940 and having their first child, Sebastian.

However, Nazism was advancing steadily across Europe, and soon the Peake family was touched by its evil. Peake had tried without success to be commissioned as a war artist, writing the beginnings of his Gormenghast series as he waited to be called up. Finally, in July 1940, he was called into service, marking the commencement of many weary years of shuttling between various training camps. In 1941 he began a commission to illustrate Lewis Carroll's 1876 poem, The Hunting of the Snark.

Mervyn Peake's illustrations for The Hunting of the Snark 1940 pic.twitter.com/5RHQVoT5no

— BookshopOnTheHeath (@BookshoponHeath) February 4, 2018

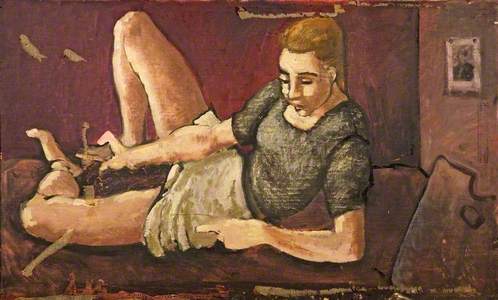

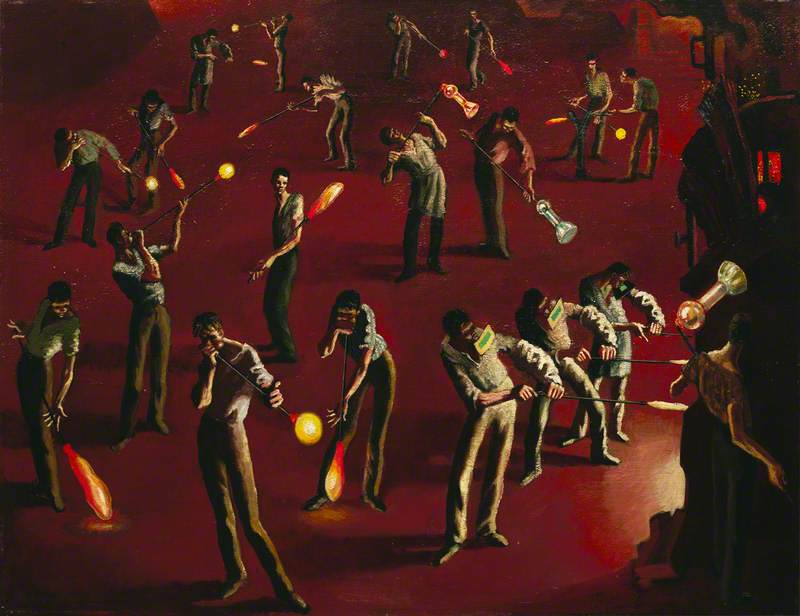

In 1942, Maeve and Mervyn had their second son, Fabian, a joyous event that was soon followed by a calamitous one – the first of the nervous breakdowns that were in some ways a foreshadowing of Peake's later illness. He was released from the army due to his ill health, and instead took on a series of paintings showing industrial war work at the request of the Ministry of Information.

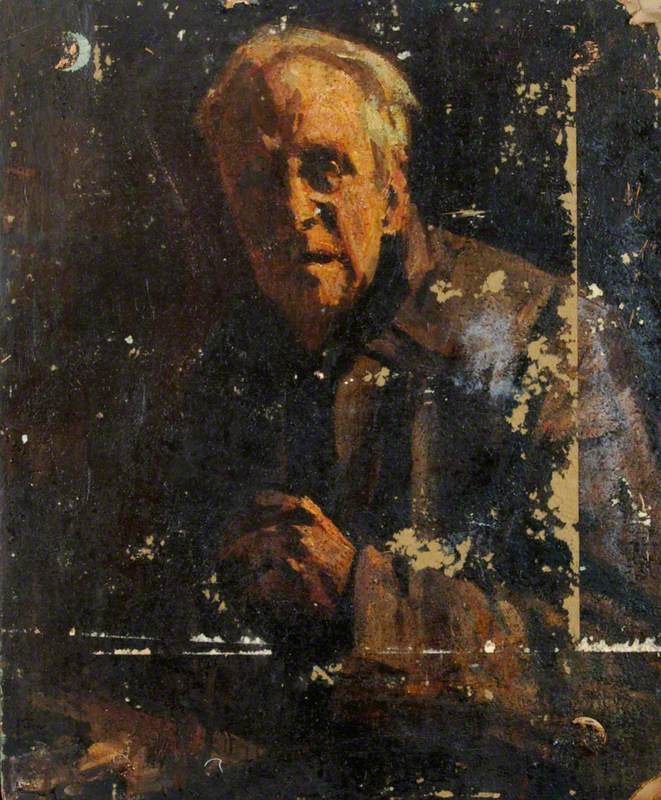

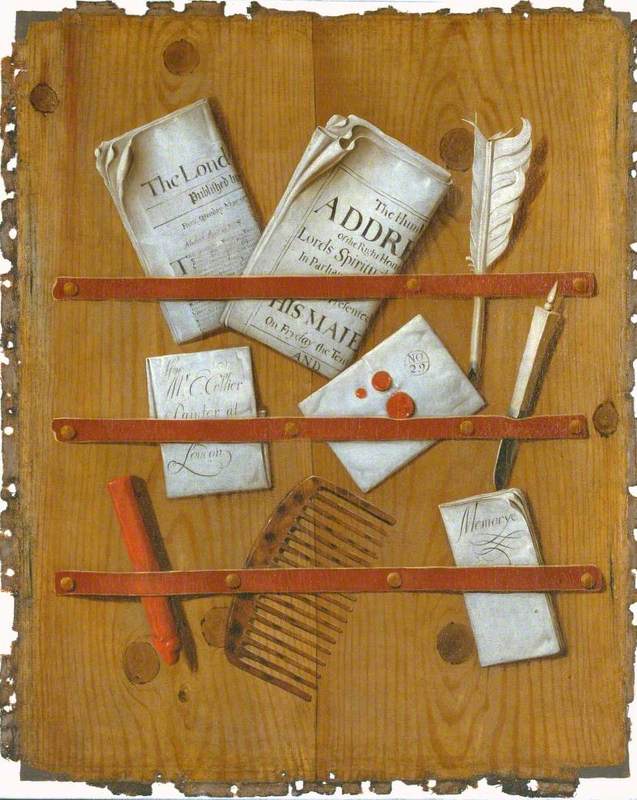

The Evolution of the Cathode Ray (Radiolocation) Tube

1943

Mervyn Peake (1911–1968)

In 1945, Peake undertook his most terrible commission, for the Picture Post, travelling to the newly liberated Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where 10,000 of its victims remained unburied, its living inhabitants often too sick to move or to survive. He wrote about and drew the horrors that he saw there, perhaps most movingly depicting a girl dying of consumption, for whom he wrote The Consumptive, Belsen 1945:

'If seeing her an hour before her last

Weak cough into all blackness I could yet

Be held by chalk-white walls, and by the great

Ash coloured bed,

And the pillows hardly creased

By the tapping of her little cough-jerked head–

If such can be a painter's ecstasy,

(Her limbs like pipes, her head a china skull)

Then where is mercy?'

View this post on Instagram

In 1945, Titus Groan was published, the first of the incomplete Gormenghast series. A year later, he and his family moved to Sark. There, Peake commenced work in earnest, turning out his Letters from a Lost Uncle, illustrations for Treasure Island and working on Gormenghast, the second in that series. Gilmore also gave birth to another child, Clare. Returning to the mainland, this time to Kent, then Surrey, Peake started Mr Pye, his novel about a plump little missionary heavily influenced by life on Sark.

In 1946, Peake also began his illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), his troubled imagination in the aftermath of war culminating in a series of surreal drawings.

However, Peake's relative triumphs were undermined by both his dire finances and the illness whose terrible hand had already been laid over his own trembling and nervously energetic fingers. At this point he was not particularly faithful to Gilmore, using his position as a teacher at the Central School of Art to seduce his students. He concentrated on writing plays during this period, with varying success. These efforts precipitated his second nervous breakdown, when his The Wit to Woo was critically panned in 1957.

View this post on Instagram

In 1958, Peake was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, for which he received electro-convulsive therapy, which can cause some memory loss. It is perhaps interesting to compare this loss of agency and memory to the endless rains and subsequent flood that drowns Gormenghast castle in the eponymous book, backgrounding the death of two of its most important inhabitants. Titus Alone was published at that time, but he was already too ill to oversee the edits, and the book was re-edited into its current form ten years later. He also began to write the next book (apart from a novella), Titus Awakes, which Maeve Gilmore wrote all but three pages of in order to give the series an almost-ending.

Then worse news came – Peake was diagnosed with 'premature senility', early-onset dementia that was almost certainly connected to his Parkinson's. He was 47, and would die ten years later, on 17th November 1968, his combined diseases rendering him unable to recognise Maeve.

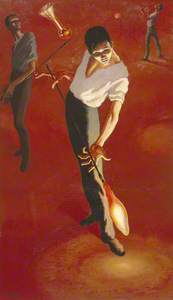

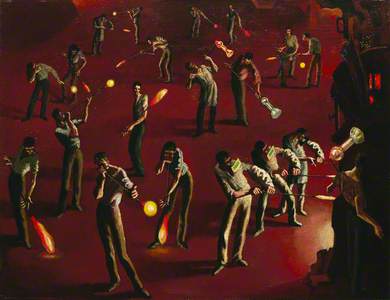

Peake died prematurely, but his indelible impact on literature has endured – though readers of the Gormenghast trilogy will never know how Titus Awakes was meant to end. Besides his writings, his legacy lives on through his fantastical drawings, illustrations and paintings.

India Lewis, writer and co-founder of @radicalwomenshistory