When Sir Edwin Landseer painted The Monarch of the Glen, around 1851, he thought he was summoning the essence of Scotland.

In his studio in London, the artist worked from sketches and studies made during travels to the Highlands. He combined and composed. The mist-wreathed mountains that loom behind the noble stag may well have been inspired by Glen Affric, as is often claimed, or they may not. Specificity, in this case, is unimportant.

The Monarch of the Glen is a painting of an idea – the idea of 'Scotland the Remote'. It is perhaps the most famous example of what could be labelled the faraway gaze – the artistic vision of a place viewed from a great distance, through a lens that belongs elsewhere. That stag looks so close you could spot the slightest twitch on its flank. But it is a fantasy, a creature cooked up from hundreds of miles away.

Taking the Deer: The Duke of Atholl with Foresters

1824–1829

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873)

To be clear – the location of Landseer's studio is not the issue. That he lived far from what he painted is not the issue. What matters is that, even when he was there, in Scotland, he saw it from somewhere else. He brought the distance with him. His was a gaze distorted by class allegiance, and by colonial attitudes towards the land and its people.

What he saw and what he did not see were determined by that distortion. The Highlands, to his eyes, were a place for the English aristocracy to play. The Highlanders, when he saw them at all, showed grateful subservience. The remoteness that Landseer summoned in his work was not an innate characteristic of the places he painted. It was a matter of perspective.

But the faraway gaze does not belong exclusively to those who reside at a distance from their subject matter. Its appeal, in fact, may be most keenly felt by artists who live and work in the very places that are likely to be labelled 'remote'. For such artists, the surest way to earn a living from one's work is to pander to some version of that gaze, to flatter and indulge it.

Every tourist town has them – the painters of jolly sailboats in the harbour, of stormy seas in tasteful blues and purples, of quaintness and prettiness and pastoral charm. These images allow visitors to take home with them the very visions of place with which they arrived. They allow visitors to have those visions unchallenged.

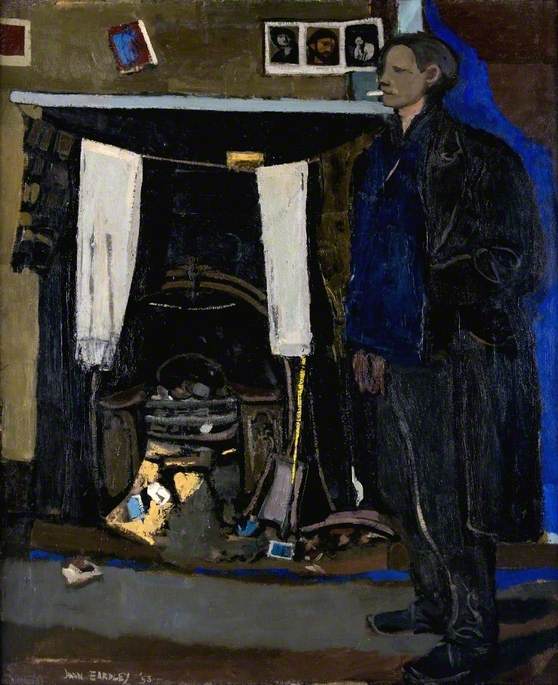

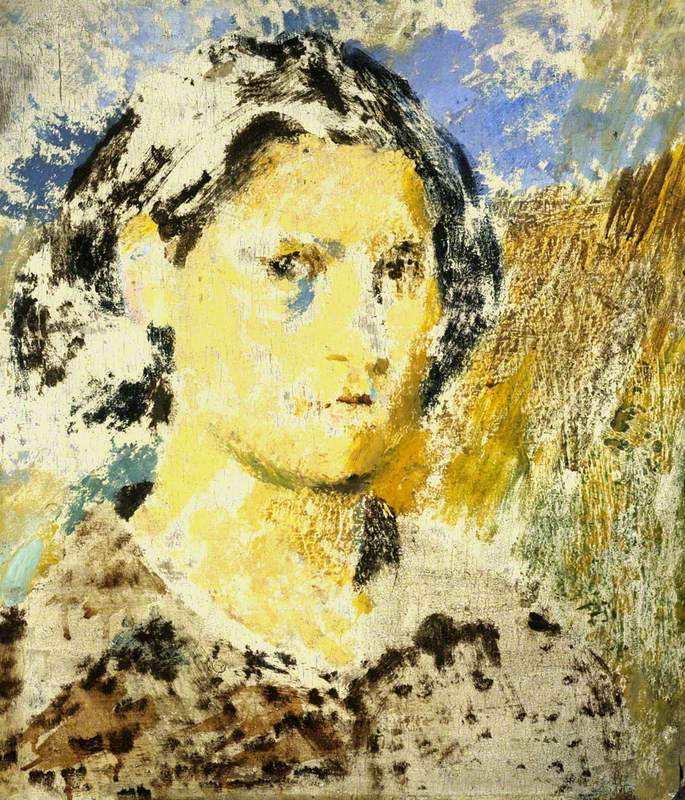

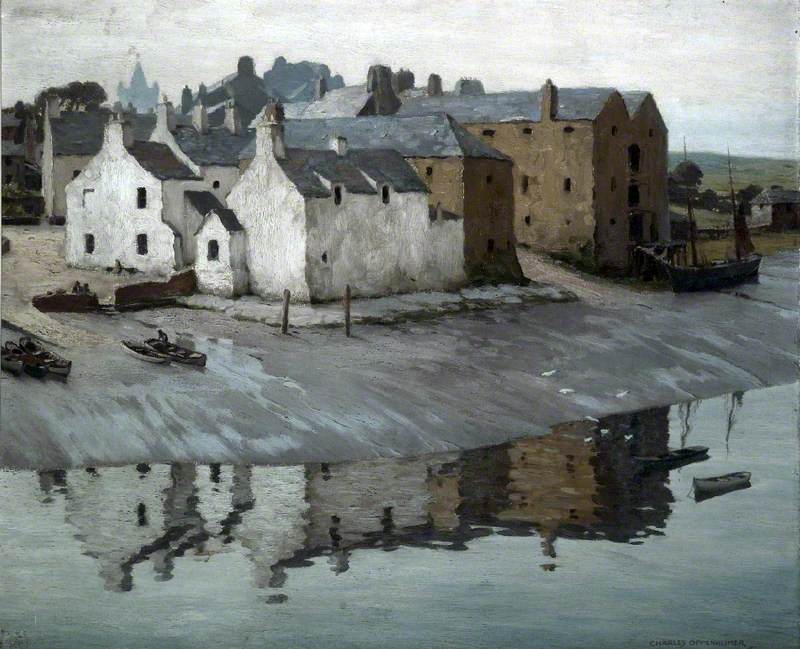

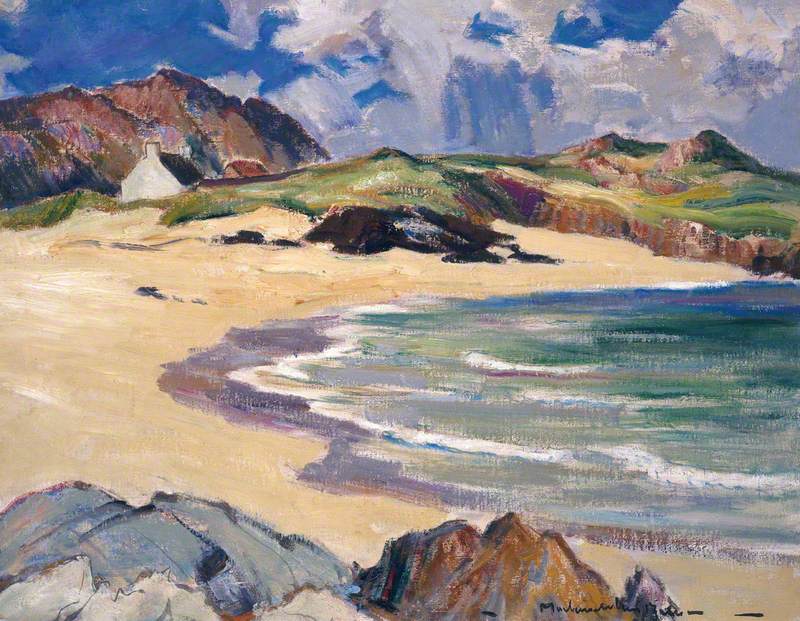

The task, then, for artists eager to resist such a gaze, is to seek its opposite: immersion and intimacy. Think of Joan Eardley, a painter who, like Landseer, was brought up in the south of England and felt the lure of northern places. She lived most of her adult life in Glasgow, and worked between there and Catterline, a village in Aberdeenshire, just south of Stonehaven.

But while those who write about her work invariably describe Catterline as a 'remote coastal community' (the language is remarkably consistent), that label does not sit comfortably with the paintings she produced there, which are characterised by a sense of closeness and immediacy, of inhabiting the landscape.

Eardley spoke of standing in one spot, day after day, week after week, allowing the weather and the seasons to provide all the change she needed. Catterline seems never to have felt small or limited to her. The more she looked, the more she saw. And though most often it is the sea or the fields around the village that dominate these paintings, the human is rarely erased completely, as it is so often beneath the faraway gaze.

A fence, a stile, a row of cottages, nets drying by the shore. Eardley immersed herself in this landscape, and in doing so portrayed the community's own immersion: people and place enmeshed. Within these paintings, it is not Catterline that is remote. It is Glasgow. It is London.

For artists who have chosen to live or work away from the cities in which the art world is centralised – no less now than it was in Landseer's or Eardley's time – a sense of peripherality, of existing at the edge of an urban understanding, is part of the context within which they have created. It imposes logistical as well as artistic challenges, this choice.

In many cases, it reduces contact with peers, for one thing, and limits access to exhibition space and other opportunities. But at the same time, it offers something to work against. Places that are imagined from afar – places that, too often, are defined by their perceived 'remoteness' – provide an opportunity to reimagine, to subvert expectations, to expand on, to complicate.

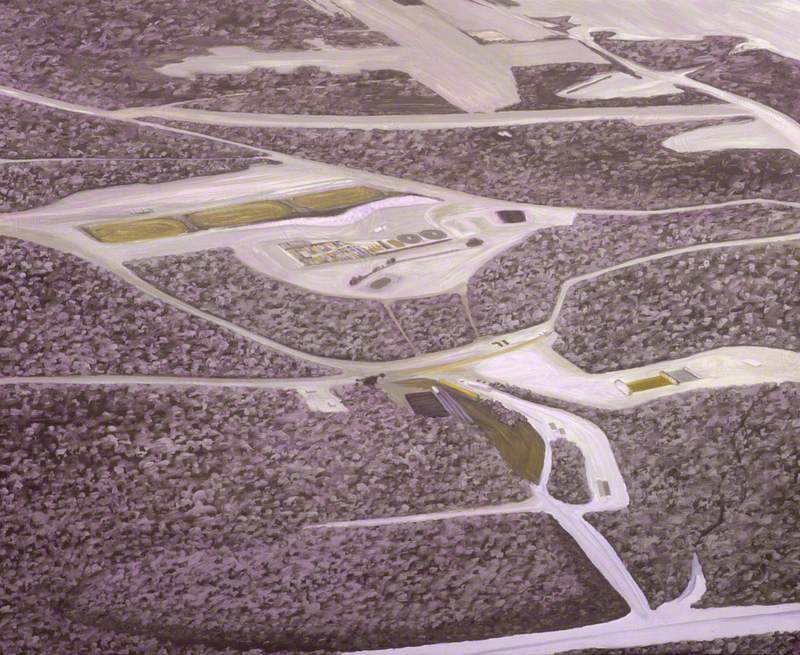

In the 1980s, Kate Downie produced paintings that focused not on the picturesque seascapes of northeast Scotland, but on its industry.

Oil rigs spewing fire above the ocean; men in hard hats, surrounded by steel; immense human structures. These images depict a space that is neither urban nor, in any meaningful sense, rural.

The rigs are remote, literally, from just about anywhere. But that word does not feel appropriate when faced with this subject matter. In the triptych Safe Harbour, monumental vessels seem to loom outward towards the viewer, the perspective emphasising what is already daunting in its scale. Everything but that harbour shrinks away towards the edges.

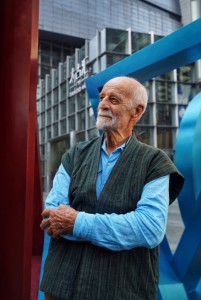

Will Maclean, born in Inverness, is also fascinated by the place of industry in the north. But it is fishing, not oil, that has primarily shaped his work. In his box constructions, found items – flotsam, bones, hooks, scraps of metal – are brought together to create objects that are tied, by provenance, to place.

In pieces such as Fladday Reliquary and Red Ley Marker, otherwise ordinary items are imbued with a poetic and mythical resonance.

These constructions attest to the artist's careful attention to both the materials and the narratives of place. They deny, implicitly, the faraway gaze.

In the regions farthest from large urban centres – the Highlands and Islands in particular – a younger generation of artists today is finding ways to connect and collaborate, to engage with their local communities and to create communities of their own.

These groups and collectives can serve to mitigate some of the practical difficulties these artists experience, living where they do. They can also offset, to a certain degree, the gravitational pull of the cities. They can generate alternative gravities.

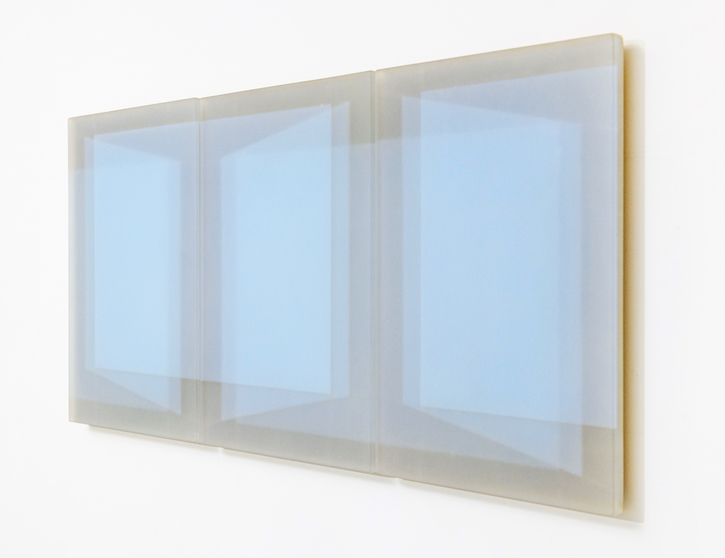

Tracing Light (Byre, Latheron House, Latheron)

2016, fused sheet glass & glass powder by Karlyn Sutherland

For many of these younger artists, an interrogation of place – of landscape, of connection, of estrangement – is, naturally, a preoccupation. Karlyn Sutherland, in Caithness, for instance, uses glass structures and architectural forms to explore the ways in which a place can be seen and mis-seen.

Pilchuck, Autumn 2019 (2)

2020, fused sheet glass & glass powder by Karlyn Sutherland

Optical illusions, light and shadow: her work plays with perspective, evoking the distortions imposed by memory, and the strange distance one can feel from something (or somewhere), even when it is right in front of you.

In Orkney, Louise Barrington also creates evocative structures – in her case, using textiles – which echo shapes within the landscape.

Poetics of Space

mixed media installation by Louise Barrington

Space, or absence, is a fundamental element of her work, making these pieces feel expansive, and impossible to define. In this, too, they reflect the islands in which she lives.

Farther north, in Shetland, Amy Gear is fascinated by the bonds between land and language, between people and the places around them.

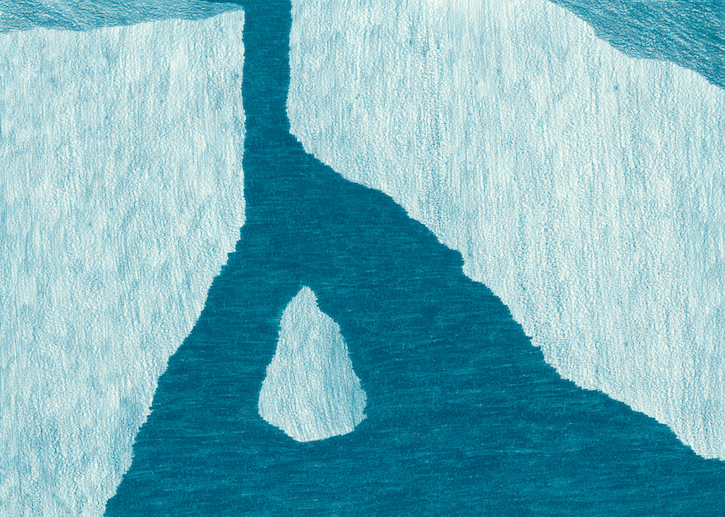

Sheltered Baby Stone

2017, pencil on paper by Amy Gear

In a series of bold, sharply delineated drawings, Landparts and Bodyscapes, Gear erodes the distinction between human and non-human forms. Tongues of ocean, limbs of land: these images express a relationship with place that is intimate, sensual, inextricable.

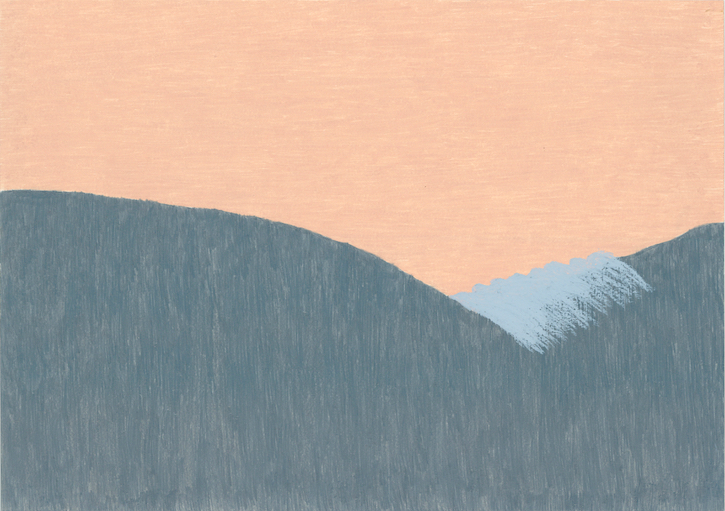

I Feel You

2017, pencil & wax pastel on paper by Amy Gear

Artists such as these could very easily pander. The regions in which they live are imbued from afar with a certain exoticism: the enduring glamour of the remote. To exploit that, to produce work that depicts their places in reductive, simplistic ways, would no doubt go down well.

But as Amy Gear makes plain, resistance to the faraway gaze is more than just an artistic choice. When self and surroundings are entwined, representation is political; it is personal.

Malachy Tallack, writer and author

This content was supported by Creative Scotland