Ah, The National Gallery –

There's plenty of landscapes, still lifes, portraits of men and women – yet not so much art that is actually by women. Oil paintings made by a female artist account for only around ten paintings in The National Gallery's permanent collection of 2,300, which equates to not even half a per cent. This doesn't count a few extra: one pastel, one made jointly with at least one woman, some loans, and also art in the gallery’s intriguing History Collection (by Paula Rego, Vivien Blackett and Maggi Hambling).

Why are the numbers so very low? Overall, the UK's entire public art collection is weighted toward male artists: one of the first public art collections to acquire work by a living female artist was Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery in 1871, with the purchase of a Sophie Anderson painting.

She was also a wife and mother, a status we have seen, from other art histories, that can often slow or kill an art practice.

Historically it has been – and arguably still is – difficult for a woman to be recognised as an artist, especially during the periods collected by The National Gallery. Its acquisitions policy aims to build upon existing strengths: Italian Renaissance, seventeenth-century Dutch and early modern French collections. The few and far between works by long-dead female artists do not come up for auction that often, hence the recent acquisition of Artemisia Gentileschi's Self Portrait... being cause for major celebration and discussion.

Does the purchase of the Gentileschi herald a new direction for The National Gallery's collecting policy? How did other women artists come to grace its walls and storage spaces, and what stories do these artworks tell?

Rosa Bonheur

Incredibly famous during the nineteenth century (there was even a porcelain doll made in her likeness), Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) was the eldest child in a French family of artists. She was unruly at school but had an exceptional talent for drawing animals. Keen to study animal anatomy, Bonheur obtained a permit to wear men's clothing – more suited to slaughterhouses and working undisturbed in public. Her lifestyle wholeheartedly defied gender norms.

Cigar-smoking, trouser-wearing and financially independent, Bonheur lived fairly openly in significant relationships with two other women during her lifetime: American painter Anna Klumpke (who had once owned a Rosa Bonheur doll), and prior to Anna, Nathalie Micas. Rosa met Nathalie when her father painted the younger woman's portrait, and the two became immediately close, soon deciding to spend their lives together. Rosa Bonheur, Nathalie Micas and Anna Klumpke are all buried together in France, under a tombstone that reads 'Friendship is divine affection'.

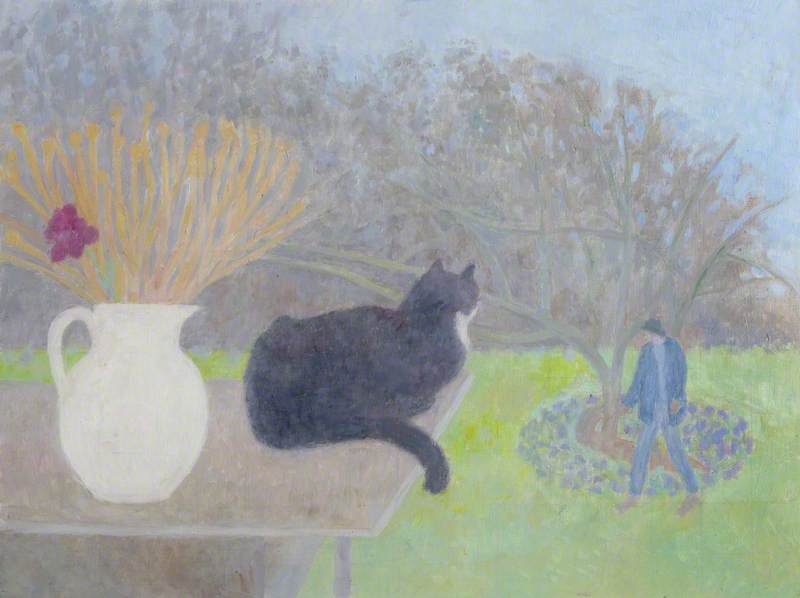

Rosa possibly painted The Horse Fair (a reduced version of a larger piece) with help from Nathalie – who assisted her partner with both artistic and household matters, freeing Rosa's time for her career. The artwork represents both a celebrated female talent as well as an important queer story in art history. It was bequeathed to The National Gallery by Jacob Bell, Founder of the Pharmaceutical Society, in 1859 – the first time art by a woman was added to its permanent collection.

Catharina van Hemessen

Portrait of a Man

possibly 1552

Catharina van Hemessen (1528–after 1587)

Where Portrait of a Man was bought in 1878, a similar, smaller portrait of an unidentified woman was presented by a 'Mrs D. E. Knollys' in 1934. The female sitter in this piece, delicately painted, is likely from Antwerp.

Catharina van Hemessen (1528–after 1587) is one of the earliest Flemish painters whose work survives today. It was rare in the sixteenth century for a woman to study art, especially as anatomy was studied using male cadavers, and younger artists apprenticed under a (male) teacher. However, Catharina circumvented one of these conformities by studying art under her father, Jan van Hemessen.

Catharina is mainly known for small, quiet and dignified portraits of women, but her career may have slowed down or ended when she married an organist in 1554. She is often cited as being not just the first woman, but the first person to create a

Judith Leyster

A Boy and a Girl with a Cat and an Eel

about 1635

Judith Leyster (1609–1660)

Similarly to Catharina van Hemessen, the career of Judith Leyster (1609–1660) slowed down after marriage. A Dutch Golden Age artist, Leyster was one of only a few female painters who joined a guild in the seventeenth century. She mainly painted genre and portrait works, and her self portrait at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. is a vibrant and energetic example – she portrays herself as a confident, smart professional, ready for work.

It wasn't until 1893 that Leyster's work was discovered, hiding in plain sight: Judith's entire oeuvre was previously attributed to her husband Jan Miense Molenaer, or to Frans

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Over a century later, and in Paris rather than Haarlem, another female artist made a

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat

after 1782

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

Élisabeth Louise Vigée (1755–1842) was first instructed in painting by her father, who died when she was 12. By Élisabeth's early 20s she was established in Paris as a portraitist. Despite having her studio shut down (she was practising without a licence) her career took off – Élisabeth was known for producing flattering portraits while putting her customers at ease with pleasant conversation. She married an art dealer, had a daughter named Julie, and produced a minor scandal when her self portrait, including her child, was revealed: Élisabeth's open-mouthed smile showed her teeth, which defied conventions.

More scandalous portraiture caused a bigger splash when Élisabeth painted Queen Marie Antoinette in loose, draped clothing (rather than her stiff formal attire). The painter became a favourite of the

The National Gallery's holdings of the artist's work include her self portrait (made in free imitation of a Rubens portrait), alongside a portrait of Alexandrine-Emilie, daughter of the architect Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart. The year after the portrait of the child was made, Élisabeth briefly took refuge in the family's home during political turbulence.

Despite navigating these challenges, the artist had a long and successful life, eventually returning to her native France. She consistently rode out controversy to become one of the most famous female portraitists in art history.

Berthe Morisot

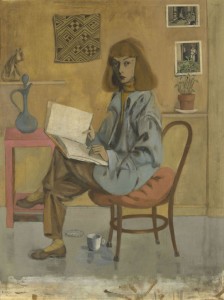

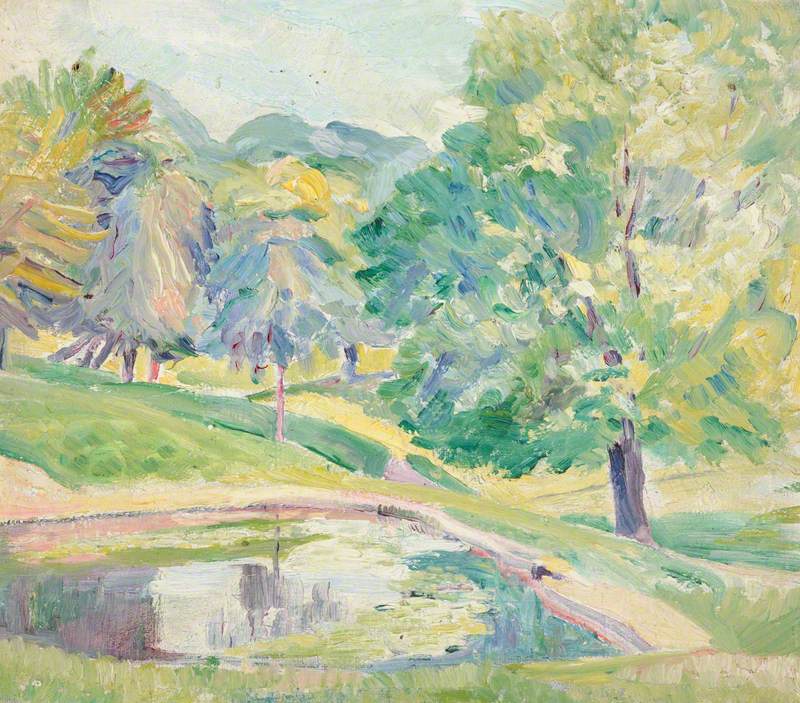

Another French painter, Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), is considered one of the first Impressionists. It is easy to overlook her delicate paintings, quickly captured en

Berthe encouraged her sister Edma to practise art, and the two were accompanied to the Louvre to learn by seeing. There, they also met young male artists such as Manet and Monet. Berthe married Eugène Manet, the brother of Édouard.

While Edma stopped painting after her marriage, Berthe kept working. She had a daughter (called Julie, like Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun), and her painting – of women, flowers, landscapes – celebrated femininity. Her art was well received and her skills were noted to develop throughout her life. Berthe painted up until her death in her mid-50s, having caught pneumonia while tending to her daughter.

Marie

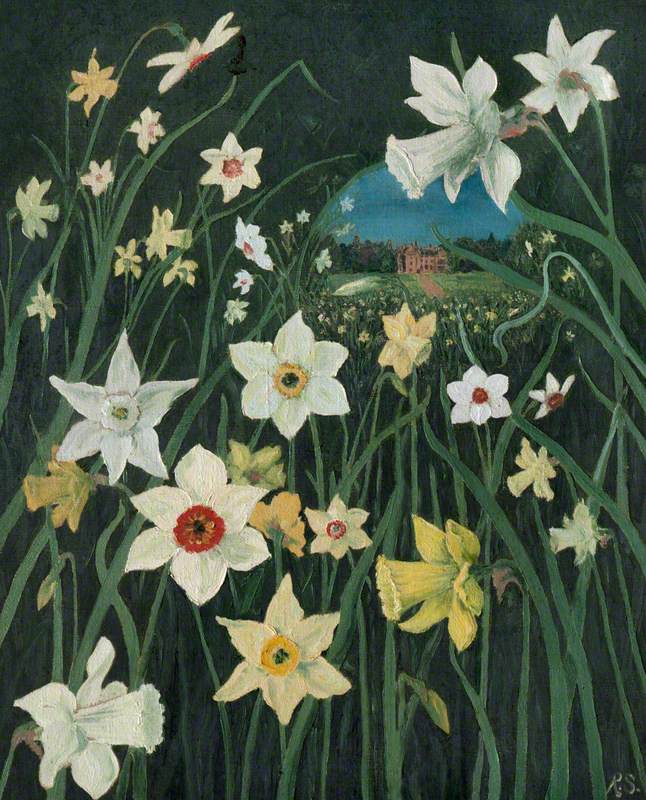

When looking at the history of art made by women, there are recurring demonstrations of what might be considered 'safe' subjects during that era. Up until relatively recently, with access to anatomical study limited at best, female artists may have chosen to follow the route of

The National Gallery holds the only known painting of the French seventeenth-century painter Marie

Rachel Ruysch

Thankfully we know much more about another flower painter, Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), star artist of the Dutch Golden Age. Daughter of anatomist and botanist Frederik Ruysch, she studied the natural specimens that her father collected and preserved. The artist apprenticed to a flower painter in Amsterdam at 15, which wasn't common for a young woman (though it must have helped that Rachel wanted to paint flowers, not nudes).

Rachel's flower paintings were not just still lifes: the artist combined specimens that bloomed at different times of the

Ruysch's success prevailed, despite having ten children and the domestic responsibilities that so often halt a female artist's development – including that of Rachel's sister, Anna. Flowers were associated with luxury and Golden Age 'tulip mania' promised any flower artist a prosperous career. Plus Rachel was hugely talented, called 'Holland's art prodigy' by Dutch writers.

Artemisia Gentileschi

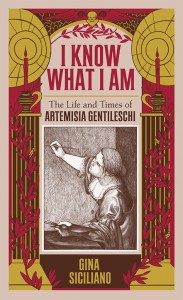

In the #MeToo era, almost 400 years after her lifetime, the story of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after) still resonates. Her rare position as a painter in seventeenth-century Italy was aided by her father Orazio Gentileschi's status as an artist. He hired Agostino Tassi as his daughter's teacher. However, Tassi raped Artemisia, abusing his position. Hoping her dignity would be restored by marrying Tassi, the pupil continued to have relations with her teacher. After realising the marriage was not to take place, Artemisia's father pressed charges. Though her rapist was imprisoned, Artemisia Gentileschi was tortured with thumbscrews during the trial, and afterwards was quickly encouraged to marry and move to Florence.

These horrible events did not halt Artemisia's progression as an artist, and the painter went on to produce extraordinary works, such as Judith Beheading Holofernes, Self Portrait as a Lute Player, and The National Gallery's new acquisition.

Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria

c.1615–1617

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

In this

Could it even be unfair to read her violent scenes, with their strong female protagonists, as autobiographical? It has been lamented that the story of her rape has become the 'axis of interpretation' for her art: the sensationalism of the story overshadowing criticism. Yet the frequent companionship and togetherness shown by her female characters suggest the artist was calling out to other women. The determination and bravery shown in Gentileschi's women defy her rapist and male subjugators. She's inspirational – the woman overcame torment to leave an artistic legacy. She was also a wife and mother, a status we have seen, from other art histories, that could often slow or kill an artist's career.

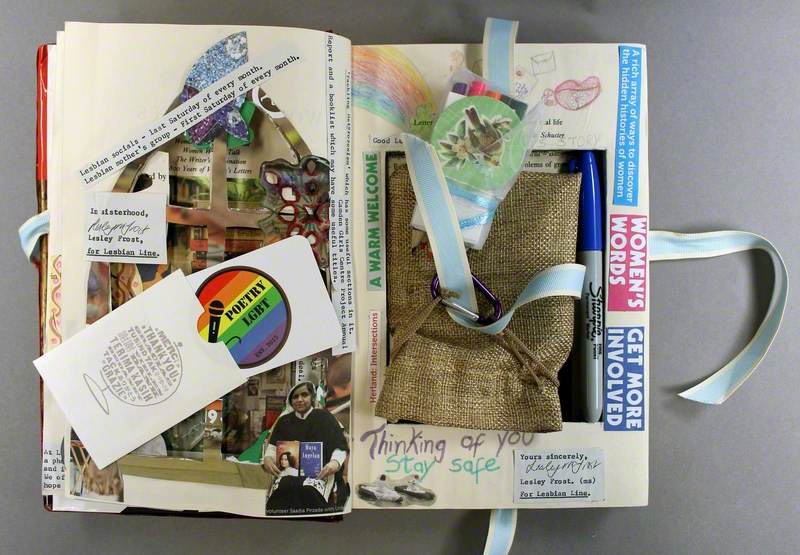

Hopefully we'll see a lot more of Artemisia Gentileschi – The National Gallery is planning the first exhibition dedicated to her work in 2020, and Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria is going on a tour starting in March 2019 with a stop at Glasgow Women's Library, just in time for International Women's Day.

Jade King, Head of Editorial at Art UK