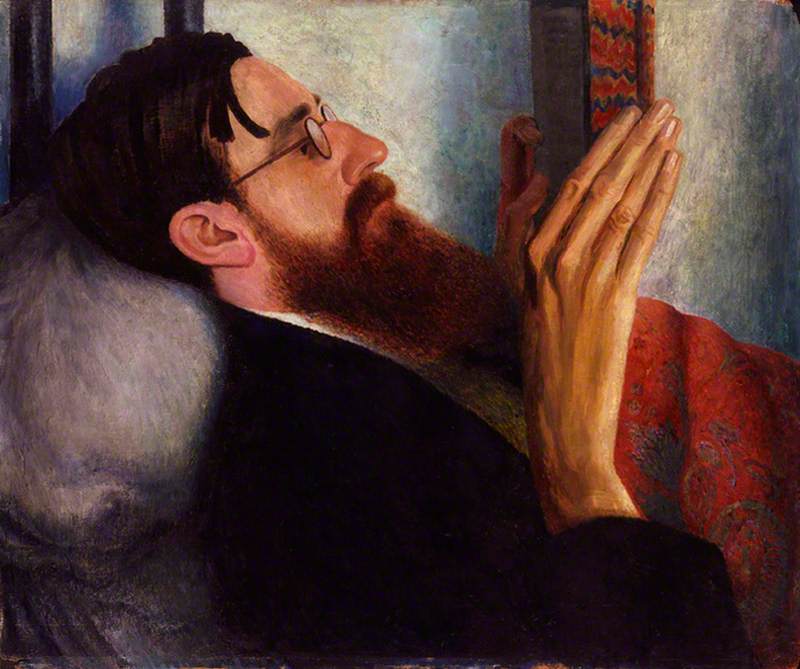

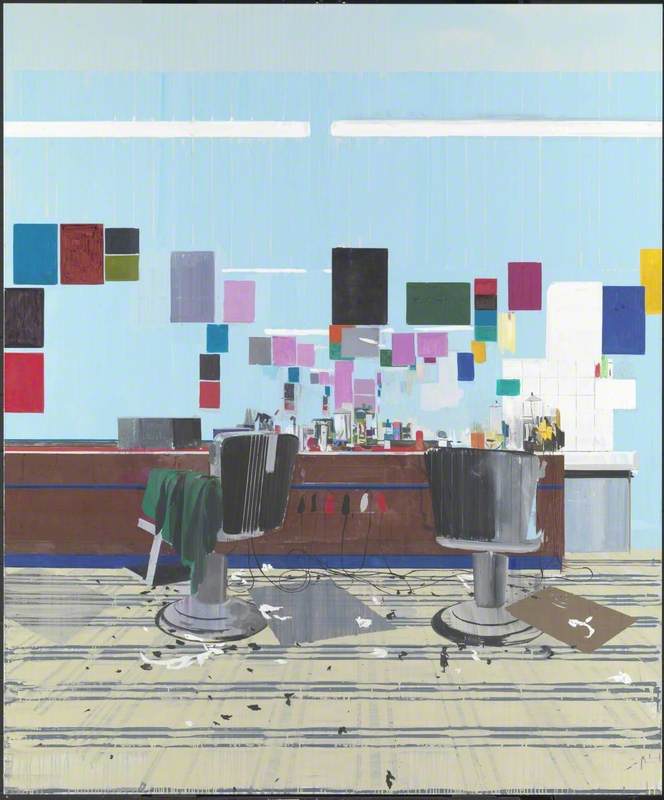

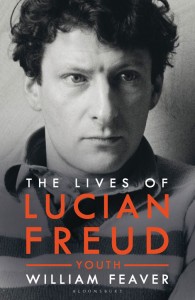

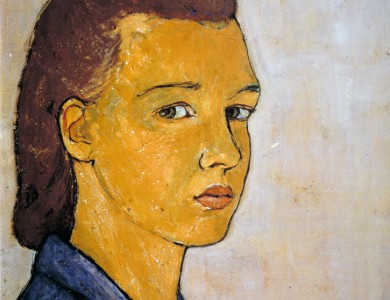

In 2018, while researching towards an exhibition of works in public collections, I noticed a curious anomaly within Art UK's artist profiles: Lucian Freud was classified as 'British, English, German'; Francis Bacon as 'British, English'; Kim Lim as 'British'; and, Anwar Jalal Shemza as 'Pakistani'. All four artists were born elsewhere (Germany, Ireland, Singapore and Pakistan) but made their careers and lives in the UK. Only some, however, seemed to be regarded or claimed as being British.

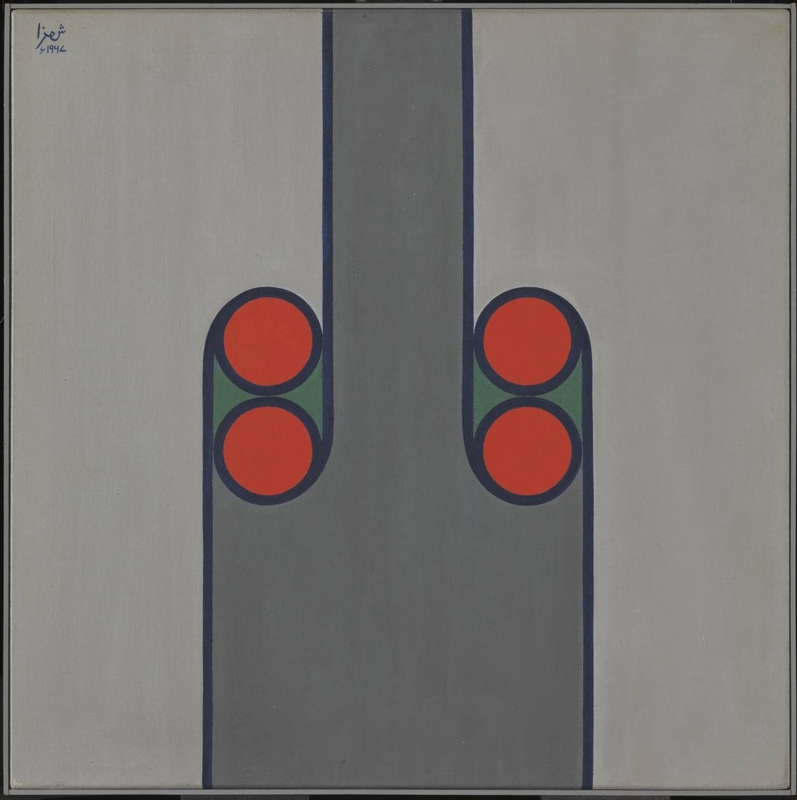

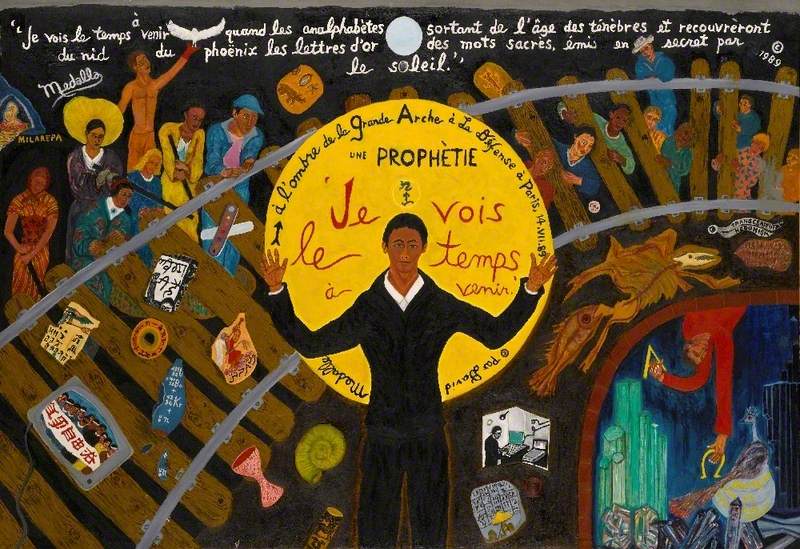

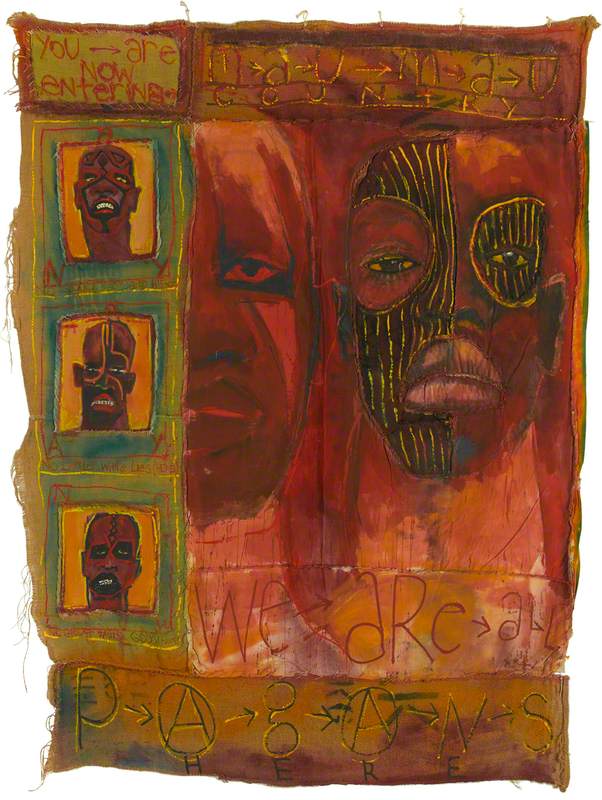

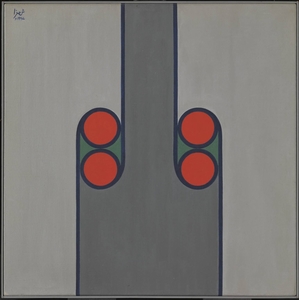

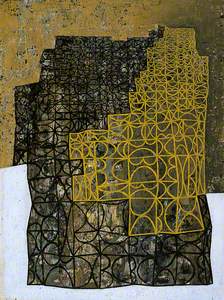

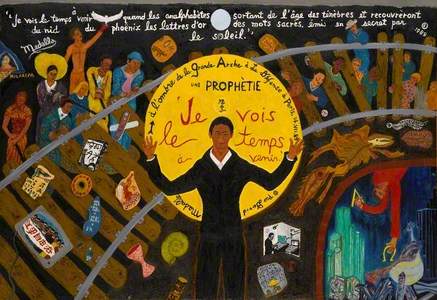

This difference in foregrounding national affiliation prompted me to point out Shemza's lack of even a hyphen (as in 'Pakistani-British') as a talking head on a BBC documentary on the making of the exhibition 'Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition', which featured the work of over 40 artists, including the four artists mentioned above (i).

Art UK provided prompt assurance that no value judgements have been made for artists whose work collectively comprises the 'nation's art' – as shared digitally on the Art UK website. The nationality field is populated by the Union List of Artist Names (ULAN) database managed by The Getty Research Institute. These discrepancies I pointed out prompted the Art UK team into investigating the tiny acts of seemingly neutral bureaucracy through which artists were shown as 'British' on their website, and in certain instances of contestation, to remove ULAN's nationality data from the artists' profile.

One year on, Lucian Freud's multiple allegiances remain unchanged on Art UK's website. Bacon and Shemza, however, have lost theirs entirely, while Kim Lim is still simply 'British'.

Prima facie, it suggests a modern art version of the infamous 'cricket test' devised by Norman Tebbit, a Conservative politician and former minister in Margaret Thatcher's cabinet; who framed Britain's cricket-loving immigrant communities' support for the national teams of their ancestors as reflecting their 'loyalty' to the British nation, and a measure of their level of integration into British society (ii). Why was Lim British but Shemza Pakistani?

While ULAN aims to be an evolving resource, it is a challenge to 'evolve' more than 300,000 artist records and 720,000 names for them. In this era of artistic mobility, it produces incongruous results. For instance, the artists Peter Doig ('British, English, Scottish, Canadian') and David Hockney ('British, English'), despite living most of their professional lives elsewhere, in Trinidad and Los Angeles respectively (in Hockney's case for more than 40 years), do not have their life choices reflected in how they are classified and claimed.

The result suggests something immutable about the 'Britishness' of their art; it is not just place of birth that determines this – as we have observed from the case of Kim Lim, who was born in Singapore, moving to London as a teenager. These seemingly insignificant acts of bureaucracy, thus, both reflect and shape what constitutes 'British art' in our museums, and through knowledge-sharing platforms such as Art UK, reinforce our national narratives.

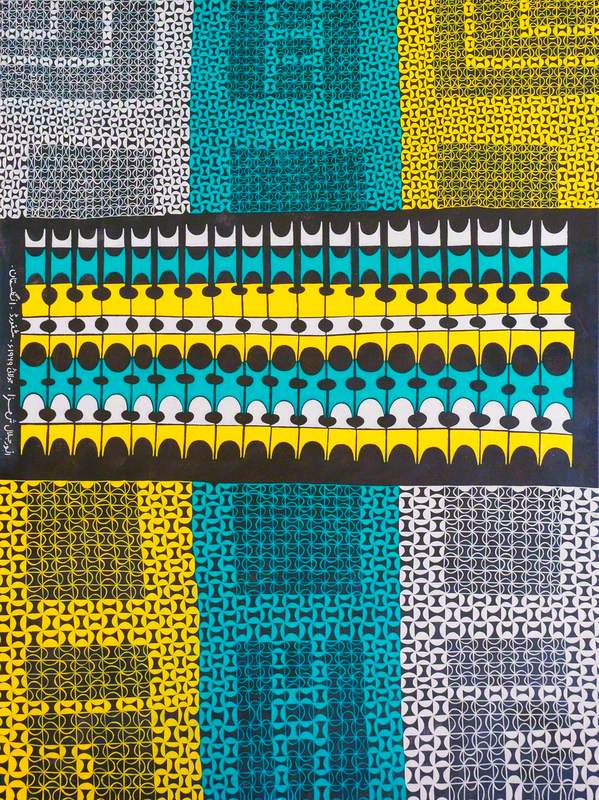

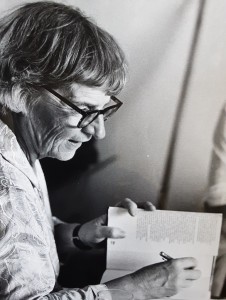

This takes us to the central question. What constitutes British art history, or indeed Britain's wider history, and how does it deal with the entanglements of Empire? Kim Lim, despite her national affiliation in the database, and Anwar Jalal Shemza are not (yet) part of the British art historical canon. Their names do not trip off the tongue of aspiring art and art history students studying modern British art.

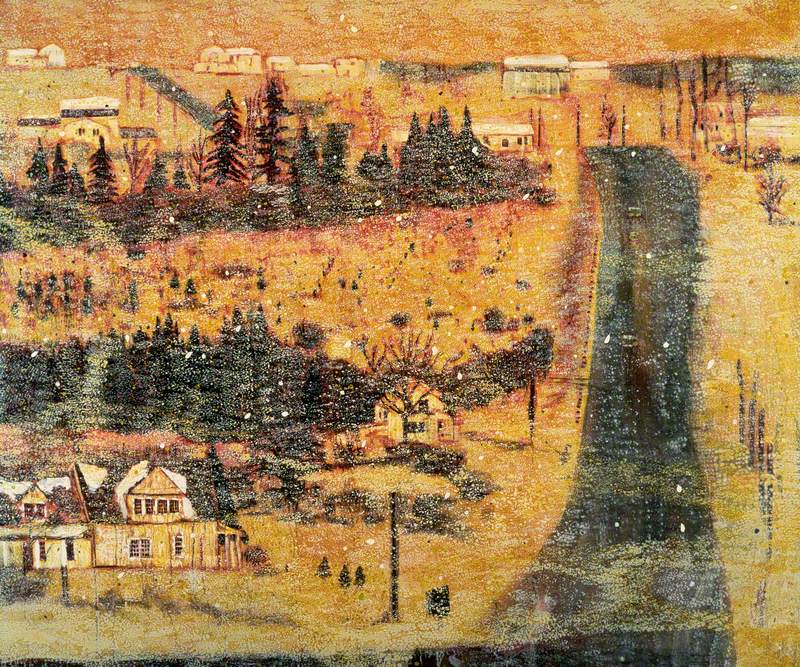

I would suggest that the fact that they were both colonial subjects of Asian heritage, who came to the imperial metropolis to be part of the modern, contributes to their remaining largely outside Britain's art history. This is at odds with our impressions of a contemporary Britain at ease with its diverse present. A casual look at the last few years of Turner Prize nominees, for instance – with British artists of Bangladeshi, Colombian, Israeli, Jamaican, Palestinian, Scottish and Tanzanian heritage – suggests an openness in the contemporary moment that is not reflected in Britain's art history.

This anomaly is at least partly a result of ours being, as I have argued elsewhere, a nation 'insufficiently imagined'. Paraphrasing the late Stuart Hall, these artists came here because we were there. But we have yet to get to grips with how we incorporate admittedly difficult histories – of the slave trade, rapacious capitalism and imperial power relations – in our foundational myths. This is not the history that our children learn in schools. It would thus be remarkable if our art institutions' historical construction were any more expansive.

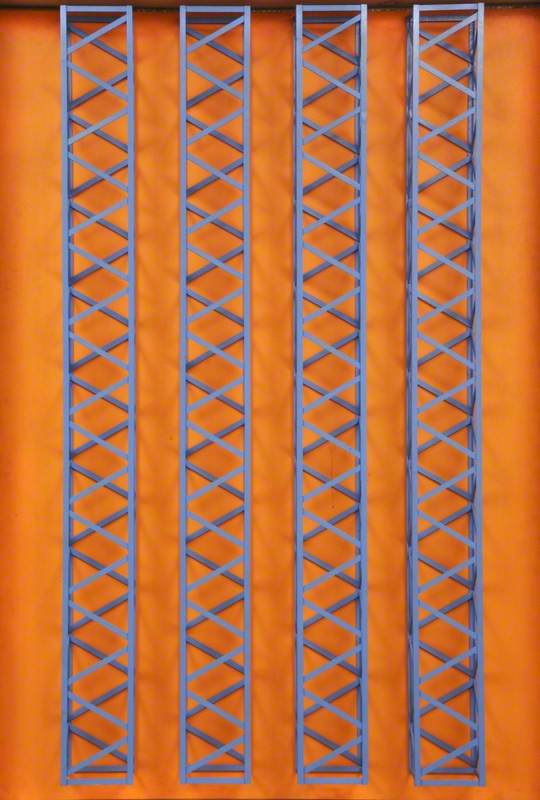

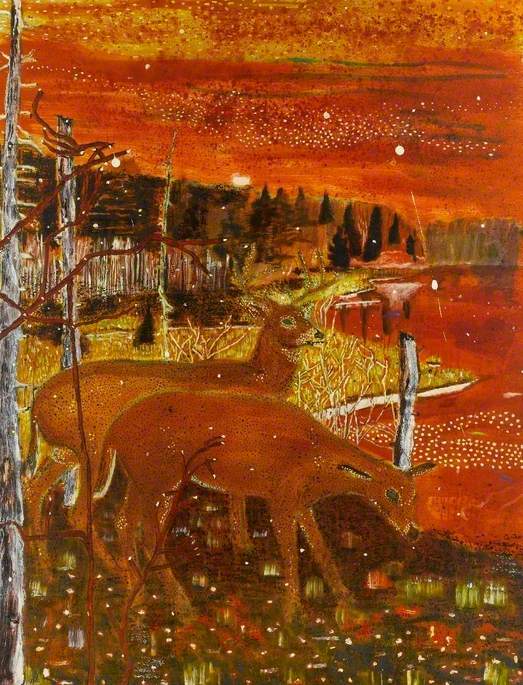

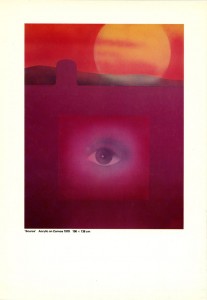

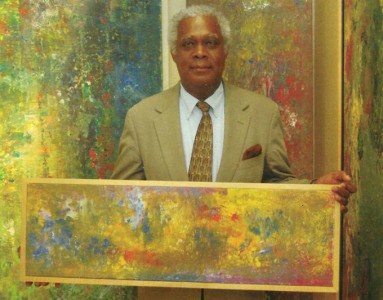

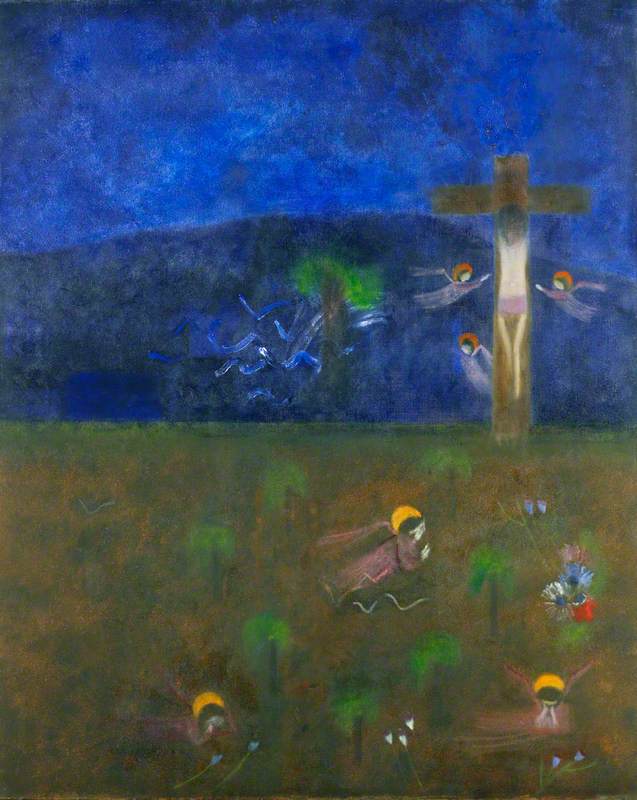

One recent example of how this manifests was the exhibition, 'Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979', organised by Tate Britain in 2016. As many critics have observed, the exhibition was notable in its omissions. For instance, it did not feature the work of Rasheed Araeen, David Medalla and Li Yuan-chia; highly influential artists (born in Pakistan, the Philippines and China, but who lived most of their professional lives in the UK), and whose experimentation with the social, political, relational, discursive and kinetic possibilities of art, expanded the very notion of what conceptual art in Britain could be.

In an ironic coincidence, work by all three artists featured prominently in Tate Modern's opening display of its new wing at the time of their absence from the 'Conceptual Art in Britain' exhibition. This suggests that it was not the significance of their art that was in question – just the quality of their Britishness.

As we steel ourselves to navigate a new path through our global relationships in a post-Brexit Britain, it may be worth our while to invest in recognising our expansive histories, and addressing the paucity of cultural stories and collections that allow us to fully imagine an idea of Britain that is capacious enough to embrace all who think of it as home.

By addressing our past we can open up our future.

Hammad Nasar, Senior Research Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Editor's note: At Art UK, we continually work to ensure our artist database is as accurate as possible. The nationality information shown on the site is pulled through from a snapshot of the ULAN database. We would like to develop the website in future so that we may list the nationalities of artists who do not have a presence on ULAN, and we would also like to develop our working relationship with ULAN so that we can share knowledge on artist nationalities.

If you spot something on Art UK that you believe to be incorrect, please click the 'Send information to Art Detective' link on a relevant artwork record, or email editorial@artuk.org

(i) 'Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition' (May 25th 2018 to April 22nd 2019) was presented by Manchester Art Gallery in partnership with the Black Artists and Modernism research project – funded by the AHRC and led by University of the Arts London in collaboration with Middlesex University. 'Speech Acts' was curated by Hammad Nasar with Kate Jesson, and its making was the subject of BBC Four documentary Whoever Heard of a Black Artist: Britain's Hidden Art History, broadcast in July 2018.

(ii) The Tebbit test was the subject of a recent Radio Four documentary Testing the Tebbit Test.