When I came to write The Beauty and the Terror, my alternative history of the Italian Renaissance, one of the questions I wanted to explore was: why is it that the big names of Renaissance art are all men? Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael... women scarcely get a look in.

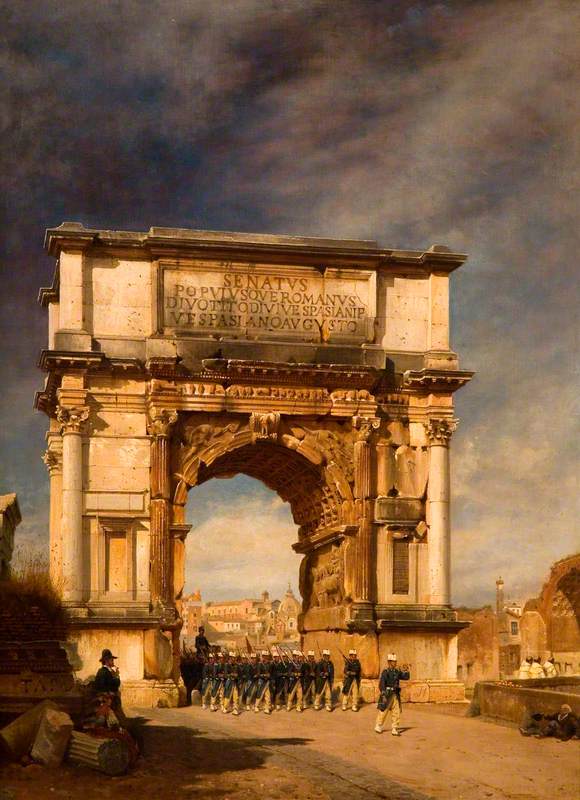

The Beauty and the Terror

front cover of book by Catherine Fletcher, published by Penguin

In his The Lives of the Artists, which established the canon of Renaissance art, Giorgio Vasari devoted only one chapter to a female artist. That was the Bolognese sculptor Properzia de' Rossi, whose chapter also had to accommodate his comments on Plautilla Nelli and Sofonisba Anguissola as well as a brief mention of the much lesser-known Madonna Lucrezia.

The question of how far women had a Renaissance (in the cultural sense) has long prompted debate. There were clearly individual exceptions, like the patron Isabella d'Este, marchioness of Mantua, who purchased and commissioned numerous works from writers and artists. Yet as the evidence is reconsidered, it's become apparent that women were active not only in the visual arts but also in the world of literature.

Portrait of an Unknown Noblewoman Seated in a Chair

late 16th C

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) (attributed to)

One barrier to the participation of women in the art world was access to training. That accounts for the large proportion of them who came from artistic families, among them the Bolognese portraitist Lavinia Fontana and, in the seventeenth century, Elisabetta Sirani.

Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist

Elisabetta Sirani (1638–1665)

Sofonisba Anguissola was an exception to that rule. The daughter of a nobleman from Cremona, near Milan, she was educated from the age of about 14 in the house of a local painter, Bernardino Campi. The portrait of her sister as a nun, painted in 1551 when the artist was just 16, shows her early promise.

The Artist's Sister in the Garb of a Nun

1551

Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1535–1625)

She benefited from the patronage of the elderly Michelangelo who showed her 'honourable and thoughtful affection', praising her work. Her images of domestic warmth and informality were novel, and she went on to serve as a lady-in-waiting at the Spanish court, where she continued to work as a portraitist.

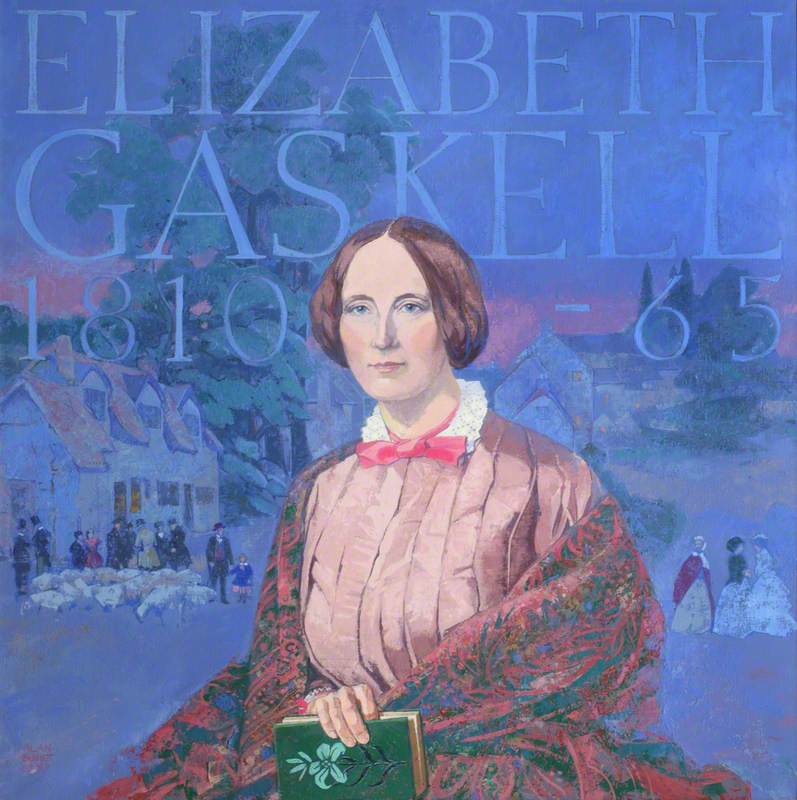

Numerous women were active in the literary world of sixteenth-century Italy, even in the face of sexism and oppression. Vittoria Colonna, member of a prominent noble family, was a poet who broke new stylistic ground, writing eloquently of the traumas of war. Yet even while praising her achievement in 'equalling the most widely esteemed and wisest men', her contemporary Paolo Giovio felt the need to add a detailed paragraph on her 'most delicate cleavage' and breasts 'swelling with heavenly nectar'.

Vittoria Colonna

1520–1525, oil on panel by Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547)

That was the polite version. An anonymous satirist claimed that after her husband's death in the Italian Wars had turned to religion only because she couldn't find a lover (or, as the writer put it, 'a pestle to grind her mortar'). As if that wasn't bad enough, her interest in religious reform attracted the notice of the Inquisition (these were the early years of the Reformation), and she was under investigation for heresy when she died in 1547.

The ferment of religious change in the mid-sixteenth century combined with long-running wars to shake up gender roles as many men went off to war, leaving women to manage at home.

The climate favoured experimentation. Chiara Matraini saw family members imprisoned and executed after a rebellion in 1533; widowed in her 20s, she embarked on a scandalous affair with a married poet and wrote extensively on that most masculine of topics: war, making the case for the superiority of learning over the military arts.

Matraini was only one of the women writers of these years whose personal relationships fell outside the conventions of marriage. Tullia d'Aragona, bastard daughter of a cardinal, was mistress to the richest man in Florence, Filippo Strozzi, and author of Dialogue on the Infinity of Love, a radical defence of women's sexual and spiritual desires. She was exempted from a ban on prostitutes wearing luxury clothing thanks to her 'rare knowledge of poetry and philosophy'.

Another of Strozzi's mistresses, however, gave an insight into the reality of such relationships when she complained that Strozzi expected her to sleep with his friends and had made her an 'object of contempt'. Veronica Franco, who also combined the careers of courtesan and writer, warned that the life of a courtesan 'always results in misery'.

Yet for all the trauma of war, widowhood and exploitation faced by these authors and poets, they had their triumphs too. In 1556 the distinguished writer Cassandra Fedele, then aged 91, was invited to give a public oration to welcome the queen of Poland to Venice, praising the Queen's 'admirable mind amid the winds of war'.

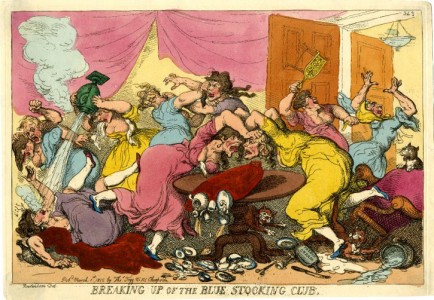

The year 1559 saw the publication of Europe's first collection of women's poetry, featuring 53 authors. Across the arts, there was much more to the later Renaissance than simply 'Great Men'.

Catherine Fletcher, historian and author

Catherine's latest book The Beauty and the Terror: An Alternative History of the Italian Renaissance is available now