This year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which decriminalised homosexuality and began the long journey to equality between homosexual and heterosexual couples. To celebrate this, we’ve already shone a light on some of the extraordinary queer stories nestled among the nation’s portrait collection – from the premature ending of E. M. Forster’s novel-writing career to the pioneering androgyny of authors Radclyffe Hall and Vernon Lee.

But what about pushing the boundaries of gender in the nation’s art itself? Many artists have turned to photography as a powerful medium to capture stories of LGBTQ communities across the world, with powerful results. It’s not something you expect to see in more traditional media.

As with most themes on Art UK, if you look, it’s there: explorations of gender, captured within oil paintings. Here we tell the stories of some very different works of art, created by very different artists, that have asked what gender really means.

Allen Jones

Starting in the 1960s, Allen Jones' collection of paintings on Art UK are bold and brash.

To put it mildly, Jones’ work has provoked debate. A quick search throws up a smattering of headlines from

The discussion largely revolves around Jones’ sculptures of women as furniture, Hat Stand, Table and Chair. Does this work hold up a mirror to the nature of gender and force us to see its absurdity – or is it just voyeuristic?

But if we step away from the lively discussion around a gold-plated Kate Moss and women as furniture, Jones’ paintings tell a more nuanced tale of gender. Two

Hermaphrodite and Man Woman are both early paintings, made six years before the controversial sculptures, and with their bold colours and abstract figures they can be seen as joyful liberations of gender. Today, the idea that gender is a spectrum is not radical (and the term 'hermaphrodite' has been retired, with 'intersex' used for people who have both male and female sexual anatomy). When Jones made these paintings, several years before the 1967 Act, the idea that we all contain elements of ‘male’ and ‘female’ was decades away from the zeitgeist, and yet this ‘intermingling of the sexes’ is a theme that resonates throughout his work.

Jones was influenced by the writings of

Rosa Bonheur

Bonheur was a nineteenth-century French artist, whose collection of paintings on Art UK are largely studies of animals in muted browns. Her most famous work, The Horse Fair, is a colossal five metres

Rosa was herself gay, remarking ‘As far as males go, I only like the bulls I paint’.

Bonheur used masculine dress as

Bonheur was a pioneering feminist, following in the footsteps of her father. But her beliefs did not make the leap into her work: she painted in a conventional, 'manly' way, wanting to capture the realism of her animal subjects (even leading one admiring critic to praise her: 'she paints like a man').

And yet, La Retour du Moulin, below, is different. The androgynous-looking figure behind the horse and the donkey may well be Rosa Bonheur herself. As described by the Walker Art Gallery:

‘... it has been suggested that Bonheur included several discreet portraits of herself in male clothes in her paintings to celebrate her nonconformity. In Le retour du moulin the miller is partly obscured, his face hidden by the shadow of his hat. Could this be one of those self-portraits?'

Bonheur suffered something of a dip in popularity during her lifetime, but recent shows have revisited her works – and The Horse Fair is on every visitors’ must-see list for the Met.

Rosa was herself gay, remarking ‘As far as males go, I only like the bulls I paint’, and she lived for some time with her partner, the American artist Anna Klumpke.

Margaret Harrison

‘I never set out to be controversial. To me, everything I tackled seemed to make perfect sense that it should be examined and that I should endeavor to find a form to deal with issues that were invisible.’

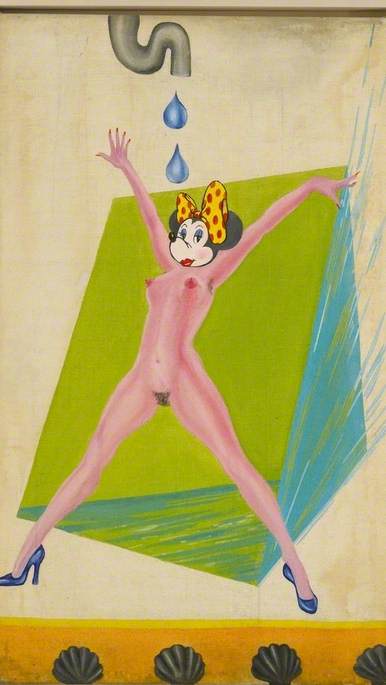

It was

The works, Harrison has said, ‘questioned the idea of having

Women of the World Unite, You have Nothing to Lose but Cheese Cake

1969

Margaret Harrison (b.1940)

The day after the show opened, it was closed down by the police on grounds of indecency.

The image of Hugh Hefner was considered too ‘indecent’ to be on public display – yet you could walk out of the exhibition, into

Harrison's later work Rape, which caused the show it was in to be moved away from the Serpentine (described as a ‘family gallery’) to the Hayward Gallery, was also used by teachers at the Battersea Arts Centre to introduce pupils to the issue. The Rape Crisis Centre held sessions for women to use the art as a jumping-off point for victims to discuss what had happened to them. It might seem from this that Harrison courted headlines: but as she said, ‘I never set out to be controversial. To me, everything I tackled seemed to make perfect sense that it should be examined and that I should

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer