Visitors that jump down the rabbit hole into the V&A museum's multimedia extravaganza 'Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser' are sure to find new ways to appreciate the enduring magic of Lewis Carroll's stories and characters.

Most memorable may be the virtual reality game and, while the show's inventive projections are certainly Instagram-friendly, the South Kensington institution has also found space for a variety of artworks that remind us how these iconic fantasies have inspired artists up to the present day.

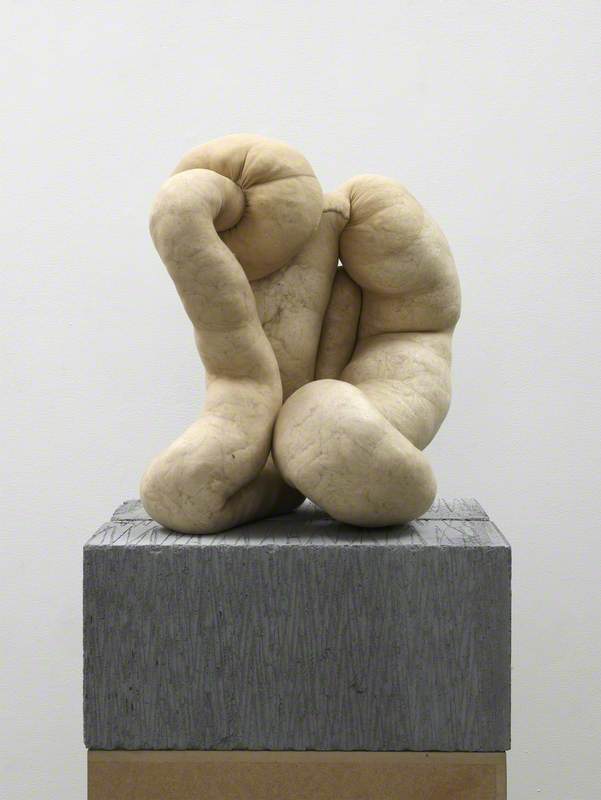

Installation image of 'Alice Curiouser and Curiouser' at the V&A

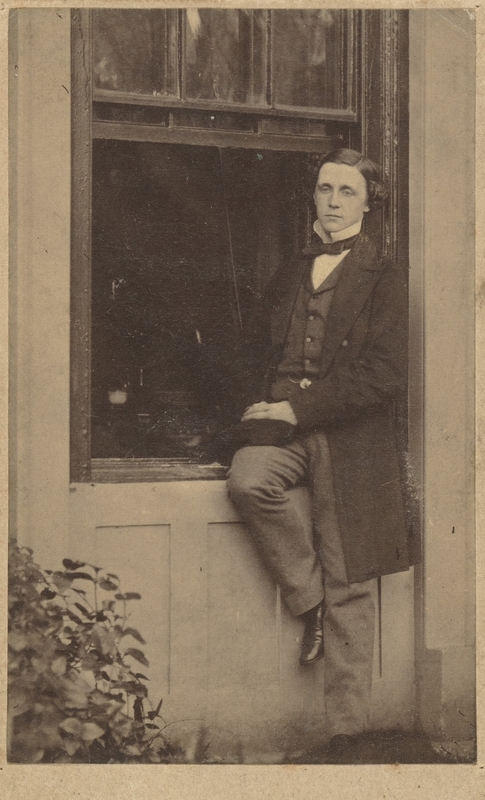

From its first appearance in 1865, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was devised as a visual work as much as a text. In the first room of the exhibition, we can marvel at the original manuscript by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (who adopted Carroll as a pen name) with his own sketches of characters, plus learn how the Oxford maths tutor recruited John Tenniel as the illustrator for its original publication.

While Tenniel's illustrations remain definitive, Carroll's creations and the ideas behind them have caught the imagination of artists down the ages, whether Alice herself, the outlandish creatures she meets on her travels or the concept that other realities are just around the corner.

He provides such rich source material because his creations reflected an especially wide range of interests, including wordplay, logic and philosophy. The art movement perhaps most associated with his oeuvre is Surrealism. In an undated note displayed in 'Curiouser', the British painter Eileen Agar wrote that Carroll was 'a mysterious master of time and imagination, the Herald of Sur-Realism and freedom, a prophet of the future'.

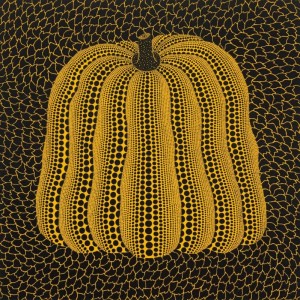

Some of the artists influenced by Carroll's work are also on show – including pieces by Edward Burra and Yayoi Kusama. Here are five more to give you a flavour of the writer's impact, beginning with the man who helped create the visual identity for Alice that still feels immediate and fresh today.

John Tenniel

It is fair to say that if Tenniel had not been commissioned to provide drawings for the first edition of Alice, his name would not be so celebrated today. Instead, he would be known in humourist circles as a long-term contributor to the satirical magazine Punch. The London-born illustrator worked for the periodical from 1850 to 1901, becoming the chief cartoonist in 1864.

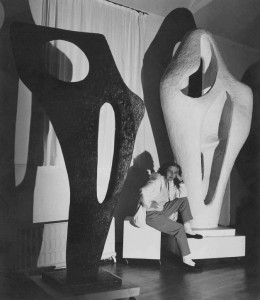

White Rabbit as the Herald

1864–1865, drawing by Sir John Tenniel (1820–1914)

A regular reader of Punch, Carroll was instrumental in selecting Tenniel as a collaborator, impressed with the former Royal Academy of Arts student's eye for detail and ability to create grotesque representations of political figures that combined realism with the macabre. The two worked closely together to achieve Carroll's vision, with the author rejecting several submissions, though Tenniel often had the freedom to invent his own characterisations.

The pair worked together again several years later on a sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). In 1893, Tenniel became the first cartoonist to be knighted for services to the arts.

Marion Elizabeth Adnams

A key fascination for Surrealists was finding the unfamiliar in things we take for granted – landscapes around us, social hierarchies and even our own bodies. Here, they found Carroll had preceded them: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland opens with its protagonist in a typical English countryside location – a quiet riverbank – before she falls down the rabbit hole.

It is in that seemingly recognisable, though also dreamlike, landscape that Marion Elizabeth Adnams placed her series of eerie paper women. Based in her home city of Derby, Adnams worked at one remove from the major Surrealist groups, yet still made a mark from the late 1930s onwards, exhibiting in local galleries and in London.

A friend of Agar, Adnams described her practice as entering what she described as 'the enchanted country'. For both her works included here, the artist cut out models of the subjects first, drawing on childhood memories of paper sculpting with her father, before translating them into paint.

Salvador Dalí

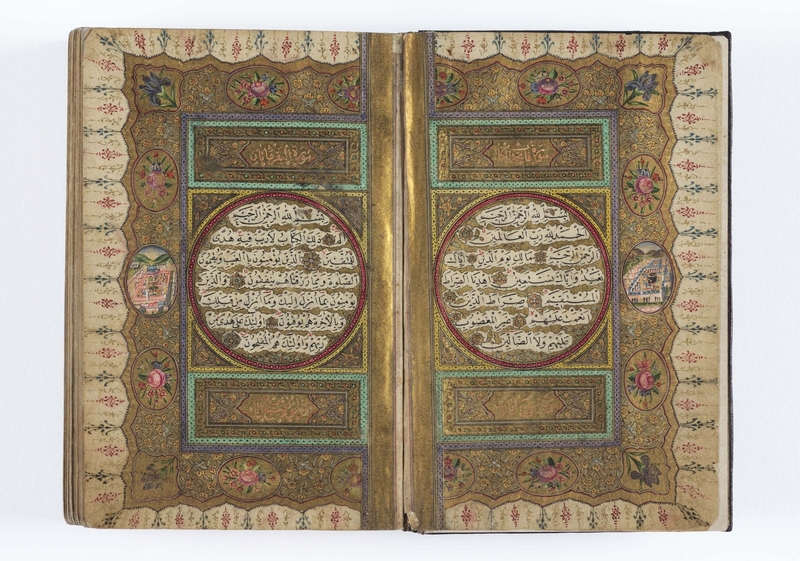

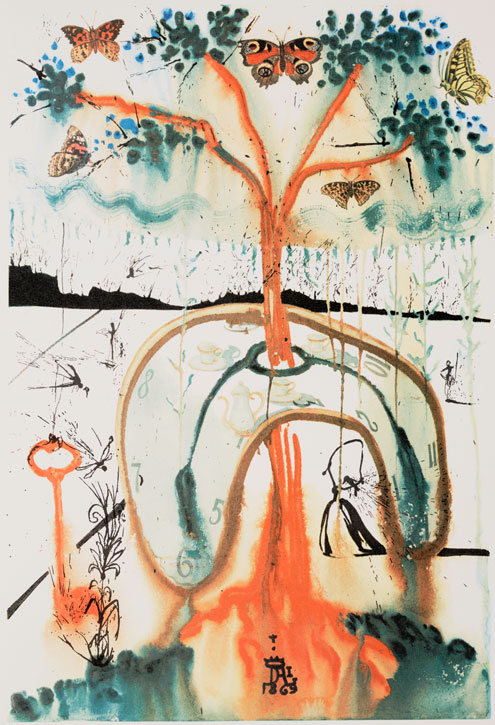

Arguably the most famous surrealist painter, Salvador Dalí enjoyed a direct relationship with Alice in Wonderland late in his career, for in 1969 the publisher Random House commissioned him to illustrate a limited edition of the now-classic work of literature. The artist created 12 original images – one for each chapter – plus an etching for the frontispiece.

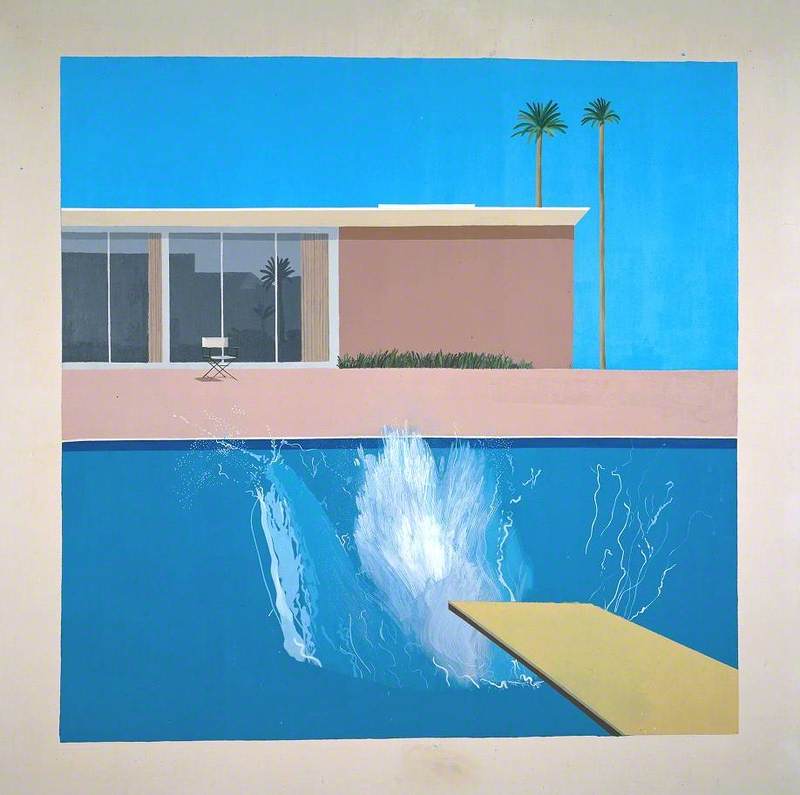

A Mad Tea Party

1969, heliogravure by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989)

Dalí used the primitive technique of heliogravure to reproduce his delicate illustrations, such as A Mad Tea Party. Here, one of his signature motifs takes centre stage – a melting clock – in the place of the White Rabbit's pocket watch that plays a key role at the Mad Hatter's tea party. The soft watch had been a familiar symbol in the Spanish artist's work since the early 1930s, seen by many commentators as a riff on Albert Einstein's theories on the relativity of space and time.

As with many of his works, the watch appears in a partly naturalistic landscape, though one more bucolic than the often arid backgrounds inspired by his Catalan upbringing. Autumnal Cannibalism (1936) takes us into a different landscape where a pair of figures attack each other with forks. It was created just after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, though some commentators suggest the apple that appears among the slices of meat that flop around like melted watches hints at the William Tell story – perhaps the destructive relationship here is between father and son.

Peter Blake

In 1969, Peter Blake, then one of Britain's most successful artists, moved from London to the village of Wellow, near Bath. In this rural setting, and with his young family around him, the co-creator of the album cover for The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band took a different direction: moving towards narrative and literary subjects influenced by the surrounding countryside.

Among the earliest work to emerge from this period was a series of eight watercolours depicting scenes of Through the Looking Glass for a new edition of the work that in the end failed to be realised. Only a series of prints emerged a few years later, showing Blake's eye for a rich colour scheme.

He even became the focus for a group of artists with similar interests – The Brotherhood of Ruralists – founded by Blake and his wife, the artist Jann Haworth, on the spring solstice of 1975. Inspired by Samuel Palmer's visionary landscapes and an earlier brotherhood, the Pre-Raphaelites, as well as the Alice stories, Blake and friends such as Graham Arnold and David Inshaw sought to update the Victorian romanticism of John Everett Millais and others.

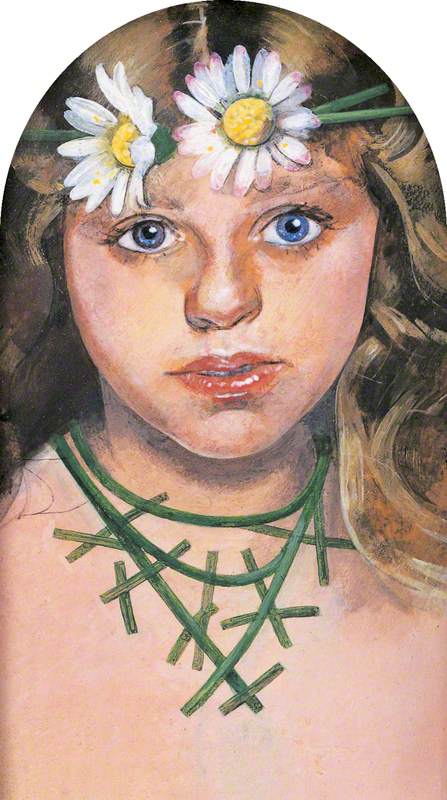

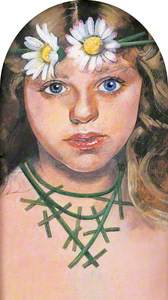

In 1981, the Tate offered Blake a major exhibition, for which he produced a body of work in this vein, including Daisy Fairy (1981–1982), a figure rooted in Blake's present as much as timeless myth.

Anna Gaskell

Early in her artistic career, Anna Gaskell forged a style of 'elliptical narratives', referencing children's stories and fairy tales, that involve girls acting out apparent stories. The two series that helped make her name, Wonder (1996–1997) and Override (1997), two images of which are shown in 'Curiouser', both reference Alice in Wonderland.

Untitled #26 (Override)

1997, chromogenic print by Anna Gaskell (b.1969)

A brave and clever figure in a strange land faced with often impenetrable or arbitrary rules, Alice has long been an empathetic and relatable role model. Gaskell, though, takes the protagonist further, using the girl in the instantly recognisable blue dress to represent the anxiety and confusion of children on the cusp of adolescence.

While individual images in these sets are numbered, there is no specific narrative to follow, just an understated sense of foreboding in Gaskell's carefully staged scenes, colour photography emphasising their apparent realism. In wonder, Gaskell varied the sizes of images to refer to Alice's growth spurts and shrinking spells, again ratcheting up the feeling of instability.

Untitled #25 (Override)

1997, chromogenic print by Anna Gaskell (b.1969)

In Override, the allusions to Carroll's visions are less direct, with versions of Alice playing roles of victim and aggressor in a twilight glow, holding each other in place in a controlling fashion to reflect the vulnerability and lack of control of those early teenage years. Like many of us, Gaskell has also been intrigued by the relationship between Carroll and the real Alice Liddell who inspired his stories.

Gaskell devised her take on Wonderland within a couple of decades of the 2015 celebrations to mark its 150th anniversary, one of many artists to find much to chew on in the life and work of a Victorian mathematician with an interest in photography. The V&A show puts her contribution in context and suggests the next half-century will see many more follow where the White Rabbit runs.

Chris Mugan, freelance journalist