Fashion has always had its influencers to bring about change, and the eighteenth century was no exception. Although the French court held sway over European fashion for the first half of the century, the Industrial Revolution and the development of overseas trade and colonies led the English to become increasingly confident style-setters.

Charles (1675–1722), 4th Lord Cornwallis

1700

Maria Verelst (1680–1744)

For the first 15 years of the century, there was very little change in dress compared with the late 1600s. Men wore a collarless knee-length coat and waistcoat, both closely fitted to the waist, and breeches. The coat had a flared skirt with pockets placed very low and a straight vent at the back. Pleated vents at the side allowed an ornamental sword to be displayed, and enormous button-back cuffs adorned the sleeves, sometimes reaching nearly to the elbow.

Henrietta Cavendish Holles (1694–1755), Countess of Oxford

1714

Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

Men's fashions had an influence on women's riding costumes. Here the Countess of Oxford wears a similar coat, also open to the waist, a white shirt with a neckcloth and a tricorne hat. The only item out of bounds for women's riding, however practical, was breeches.

A Conversation (The Artist's Brothers Peter and James Romney)

1766

George Romney (1734–1802)

Waistcoats were similarly constructed to the topcoat, buttoning from top to bottom. Varying trends in which buttons to fasten meant that tailors could include many non-functioning buttonholes. Here Peter and James Romney proudly display a trend for leaving a few of the middle buttons undone.

While expensive waistcoats were often elaborately embroidered at the front, the backs would be made from a plain, inexpensive fabric. Underneath, a man wore a cambric or muslin shirt with full sleeves ending in ruffles or lace. This portrait from 1750 demonstrates how little change there had been in men's dress since 1700, the main difference being the shorter wig with its neat side curls.

James Ainslie, a doctor, wears a restrained wool suit typical of a middle-class professional. After 1760, coats were cut away at the front. His breeches are fastened just below the knee with a row of buttons and a buckle. Until about 1730, stockings were pulled up over the edge of the breeches but after that, the breeches fastened over the stockings, with buckles eventually fully displacing buttons.

Ann Costello, Daughter of John Costello

1720–1730

Thomas Hudson (1701–1779) (attributed to) and Charles Jervas (c.1675–1739) (attributed to)

At the beginning of the 1700s, women enjoyed a relatively relaxed and comfortable form of dress. Ann Costello is wearing a mantua, which was a trained gown, open at the front and draped at the hips, with the train pinned up behind. A sash held the train in place at the waist and the gown was worn over a matching skirt of the same fabric, known as a petticoat. The mantua had its origins in the late 1600s, when it was a form of 'undress', implying any garment worn for daytime activity and distinct from the 'full dress' required for the evening.

Underneath her mantua, a woman wore a chemise – a knee-length garment made of linen. This prevented the expensive silk from touching the skin and could be laundered regularly. Ruffles and lace trimmings stitched to the neck and cuffs of the chemise were designed to be visible at the neckline and sleeves of the gown. The artist Joseph Highmore picks out the contrasting blue lining of the silver-grey dress and the reverse side of the train. Portrait painters particularly liked to depict their sitters in plain silks as it enabled them to show off their mastery of texture and sheen.

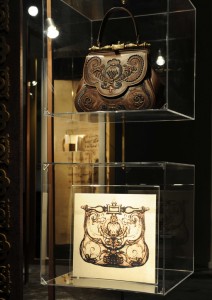

Stays

1780–1789, linen, linen thread, ribbon, chamois & whalebone, made in Britain

Women of all classes wore stays over the chemise. Stays comprised a wool or linen bodice stiffened with thin flexible strips of baleine (whale cartilage) or cane. They could be adjusted with a lace which criss-crossed through eyelets down the back, while tongues of fabric at the waist allowed for movement around the hips.

Queen Charlotte (1744–1818)

(after Thomas Gainsborough) late 18th C

Christopher William Hünnemann (1755–1793)

By the 1730s, the mantua had evolved from relaxed fashionable dress into a formal garment. It was required dress for court, where Queen Charlotte continued to insist on it into the nineteenth century, 20 years after women had adopted the diaphanous muslin gowns of the neoclassical age.

Gowns became closer fitting, with an open v-shaped bodice and inverted v-shaped skirt, revealing a decorated petticoat supported by a hooped underskirt. A stomacher, stitched or attached by pins into the bodice, could also be laced into the stays to keep it taut. An elaborate stomacher was a signifier of wealth and refinement.

Stomacher

1710–1730, silk, linen, silver & gold, made in Britain

Initially, hooped skirts were bell-shaped, but by 1735 the more luxurious had developed a flat front and back and preposterously wide hips. To achieve this shape, baskets made of whalebone or cane, known as panniers, were slung on each hip.

Mantua

1753–1760, silk, linen, silver, gold & brocade, woven in France, made in England

Practical problems naturally ensued with women unable to dance, pass through doorways or sit side by side. At the first performance of Handel's Messiah in Dublin in 1742, ladies were politely requested to refrain from wearing their hooped petticoats.

Mary Cawthorne (1724–1796), Mrs Morley Unwin

c.1750

Arthur Devis (1712–1787)

Mary Cawthorne has pulled up the panniers of her dress in order to sit comfortably on a garden seat. Her fashionable quilted underskirt helps support the gown and keep her warm. By 1750, necklines had become low and square and so she tucks a muslin kerchief into her décolletage for modesty.

The sack-back gown, also known as a robe à la française, was another form of mantua. It had distinctive double box pleats flowing from the back of the neckline, creating an elegant silhouette. The train was also a perfect canvas for brocaded or painted silks. Almost all gowns were made of four widths of silk at the back and two at the front, with the tucks and pleats arranged to accommodate the wearer.

The serpentine twisting of the ruffled trim of Mrs Bowles' sack-back is inspired by the irregular and ornamental characteristics of the Rococo style which originated in France and flourished in England between 1740 and 1770. The decorative fan shapes on the petticoat have a raw edge pinked into scallops, a popular feature on such dresses.

Madame de Pompadour's reputation as a fashion icon helped disseminate the Rococo style. Her robe here brims with theatrical flounces, frills, ribbons and bows. After she popularised a particular shade of pink created by the Sèvres porcelain factory, it was named 'Rose Pompadour' in her honour.

However, the increasingly prosperous English middle classes started to influence fashion in their own way. A vibrant textile industry produced silks, wools and cottons for home consumption and mass-produced block-printed cottons reached a wide market. The comfortable lifestyle of the Shudi family is evident in their clothes. Catherine wears a sack-back with a full pink petticoat, carefully highlighted by the artist. The younger boy wears a dress, as all small children did, but the older wears a miniature version of a man's suit. Burkat Shudi, a harpsichord maker, relaxes in a banyan, a form of undress inspired by the Japanese kimono first imported by the Dutch East India Company in the 1650s.

The banyan was not unlike the early mantua worn by women and was favoured by men of an artistic or philosophical bent, as well as by portrait painters who appreciated their timeless quality.

Henry Fiennes Pelham Clinton (1750–1778), Earl of Lincoln

Gainsborough Dupont (1754–1797)

In the mid-eighteenth century, a vogue for 'Vandyke' dress emerged. For men this meant a plain silk suit with lace collar and cuffs, and for women a loose robe adorned with ruffles and rosettes, redolent of fashions worn over a hundred years before. Horace Walpole, describing a masquerade in 1742, marvelled that 'all kind of pictures walked out of their frame'.

Clothing was valued, as it was cut and sewn by hand, the sewing machine only being invented in the nineteenth century. Garments were frequently adapted to new trends, cut down and reused. As silk was particularly costly, a dress might be retrimmed many times or passed down to poorer relatives, friends or servants, or even to churches for altar frontals or vestments.

In April 1782 the Ladies Magazine reported another sudden change in fashion: 'The Queen of France has appeared at Versailles in a morning dress…said to be the universal rage…It is drawn up in the front on one side and fastened with tassels…this discloses a puckered petticoat of gauze.' This new style, commonly known as the polonaise, had skirts a few inches shorter than before and showed a tantalising glimpse of ankle.

Englishwomen adopted a more moderate bell shape with a bustle rather than hoops, but as muslin became increasingly popular the silhouette grew slimmer, heralding a new softness and simplicity in women's fashion. A love of rustic pleasures combined with a growing interest in ancient Greece and Rome gave rise to loose, straight dresses with a gathered neckline and long narrow sleeves. The new high waistline was set off with a colourful sash and the whole look enhanced by a wide straw hat.

The French Revolution of 1789 had a profound effect on fashion. In France, anti-aristocratic sentiment meant that any form of ostentation in dress was risky. French women followed the example of socialite Madame Récamier, adopting flimsy gauze dresses inspired by the classical world, a style soon taken up by their English sisters.

However, for men, it was the understated suits of the English country gentlemen that influenced their style and appealed to the newly liberated French. The tailcoat, made now from wool, was cut away at the front and worn over a short patterned waistcoat, often striped. The style gained universal favour across Europe.

The many ups and downs in eighteenth-century fashion were lampooned in satirical prints. Here the bewildering changes are embodied in an elderly lady in a hooped dress and neat cap looking critically across at a young lady from the late 1780s in a slim outfit featuring a masculine 'redingote' (riding coat) collar and large buttons, topped by a vast straw hat. If we think fashion moves fast in our own time, we should perhaps pay attention to the Georgians.

Lucy Ellis, freelance writer and editor

Further reading

J. Anderson Black & Madge Garland, A History of Fashion, Black Cat, 1990

Avril Hart & Susan North, Historical Fashion in Detail: the 17th and 18th Centuries, V&A Publications, 2005

Aileen Ribeiro, The Gallery of Fashion, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2000