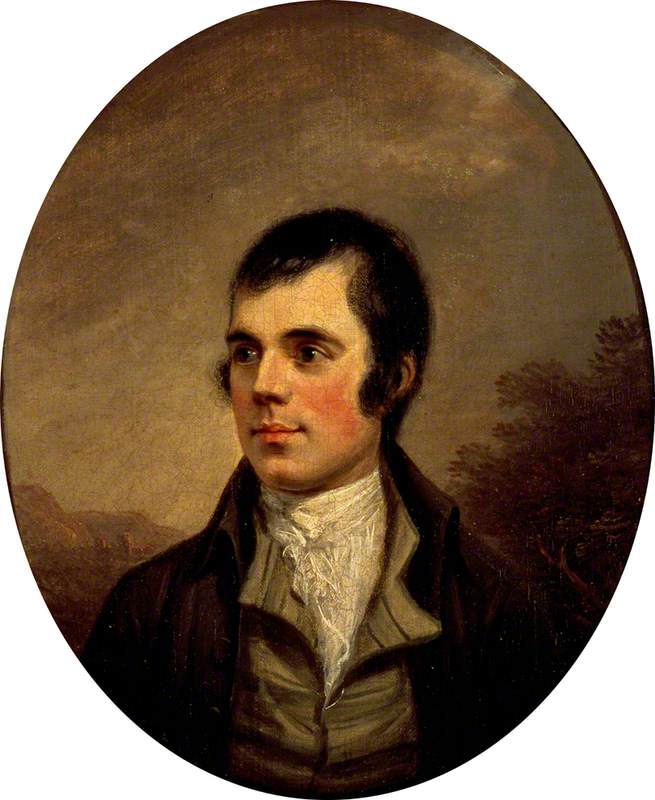

In anticipation of Burns Night (25th January), let's look at a visual retelling of the epic poem Tam o' Shanter (1791) by Scottish literary icon Robert Burns (1759–1796).

Burns Night is the annual celebration of the poet's birthday, and it's become a worldwide affair. You don't have to be Scottish to join a raucous ceilidh (pronounced KAY-lee) and enjoy a haggis supper while drinking a wee dram of whisky (or possibly more).

However, Burns' poem – known for its comedy, pathos and social commentary – was also a warning, directed towards those eighteenth-century lushes who couldn't hold their liquor. The message still holds resonance today.

Burns wrote Tam o' Shanter in 1790, and it was published the following year in the Edinburgh Herald. Written for his friend Captain Francis Grose, Burns had agreed to provide a story to accompany illustrations for Grose's book, Antiquities of Scotland.

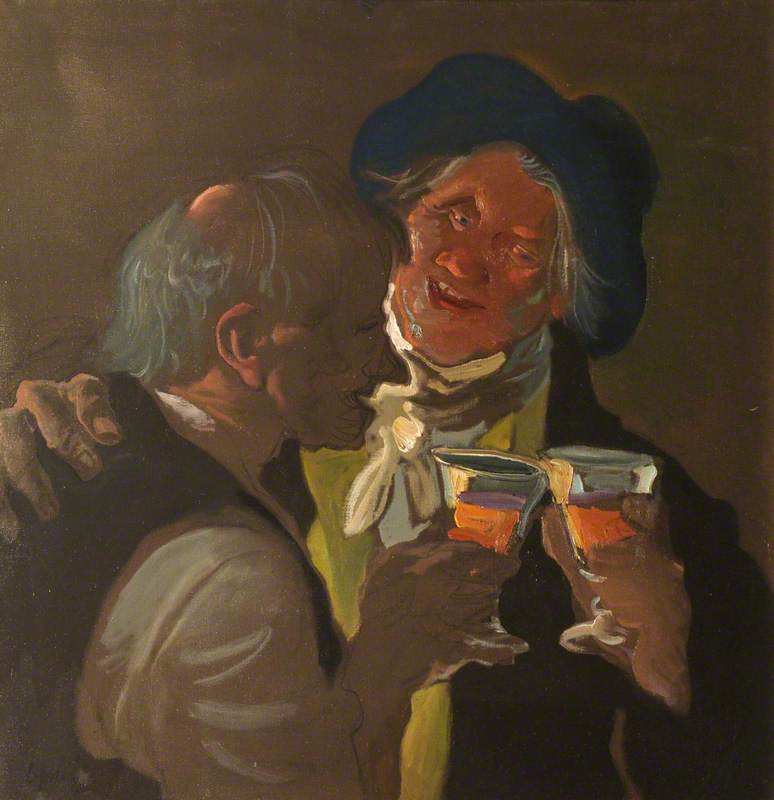

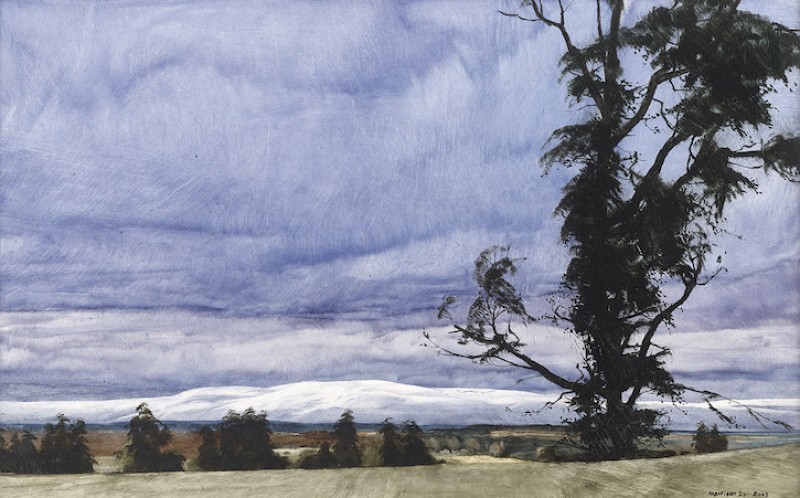

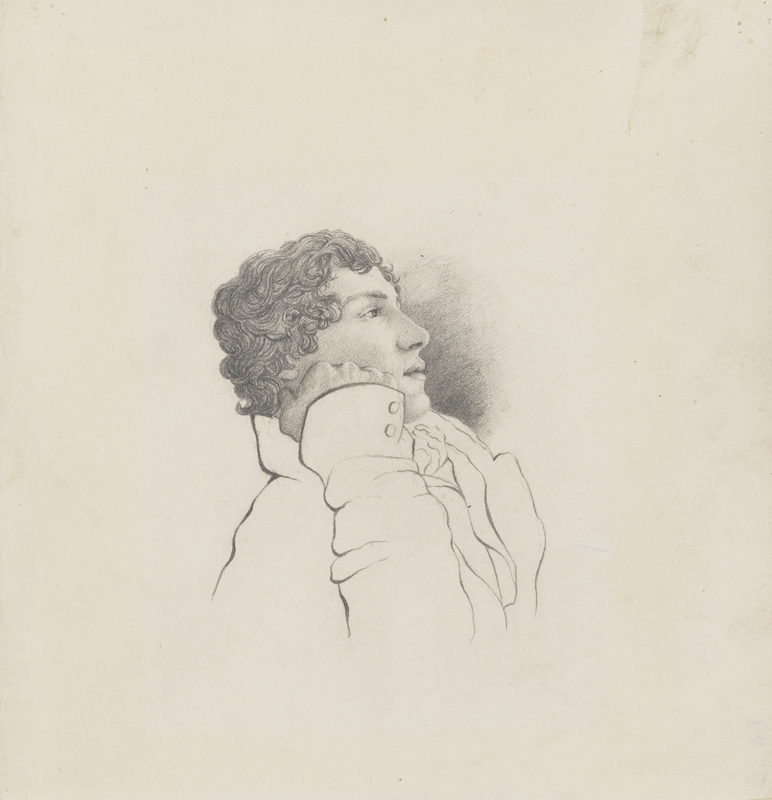

The Meeting of Burns and Captain Francis Grose

Robert Scott Lauder (1803–1869)

Set in the Scottish town of Ayr, the poem tells the tale of Tam, a boozy (yet loveable) farmer, his long-suffering wife Kate, and his loyal horse Maggie.

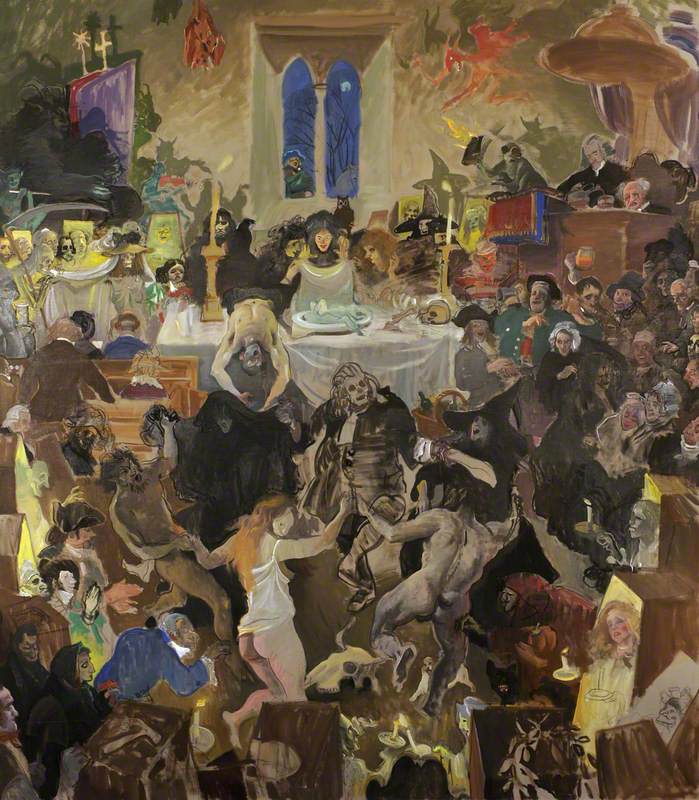

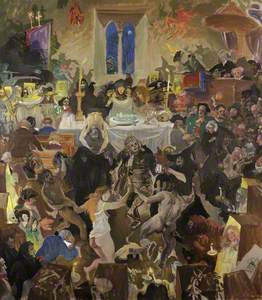

On his way home, after a night of heavy drinking, Tam and Maggie stumble upon curious activities taking place at the haunted sixteenth-century Alloway Kirk, which still stands in South Ayrshire today. Tam peers inside of the kirk, where he sees a supernatural spectacle – witches and warlocks partying with the devil.

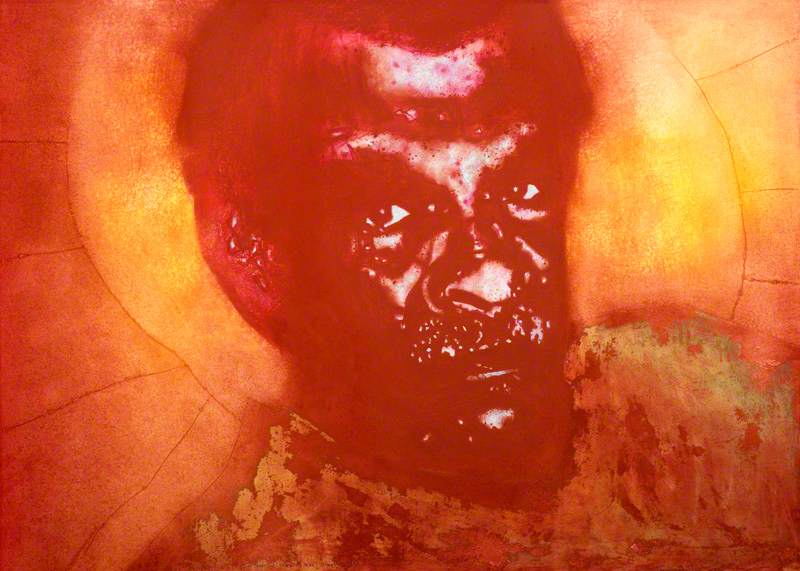

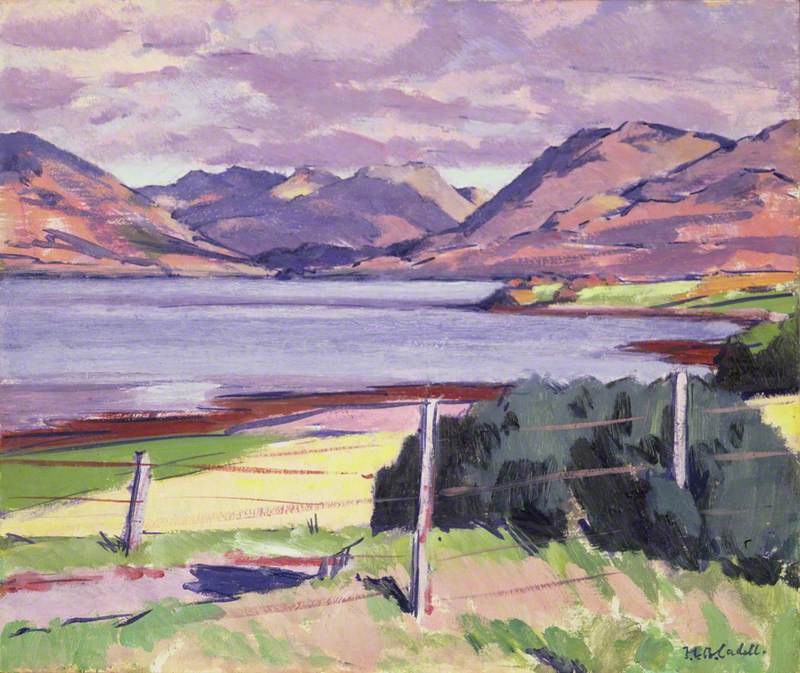

Alloway Kirk from the East

1816

John B. Fleming (1792–1845)

Instead of quietly retreating from the frightening scene (as any sane and sober person would do), Tam decides to heckle a bonny lass in a short nightshirt, who turns out to be a witch named Nannie Dee. She is nicknamed 'Cutty-sark' (literally meaning 'short chemise' – the name of the famous tea clipper originates from this story).

Unsurprisingly, Nannie Dee does not enjoy peeping Tam's catcalling. What follows is a wild macabre hunt for Tam and Maggie, who narrowly escape death as they gallop with full speed back home, where Kate waits up for her philandering husband. Unfortunately, the real hero of the story – Maggie – loses her tail along the way.

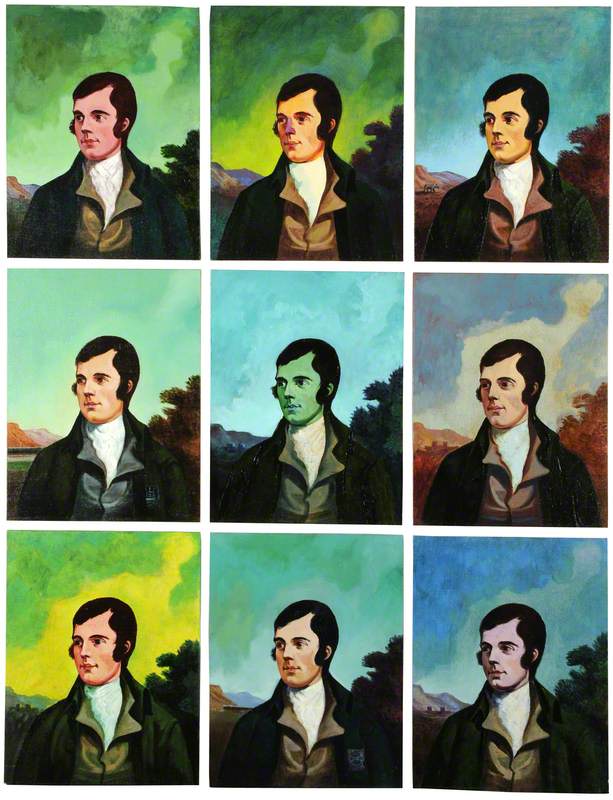

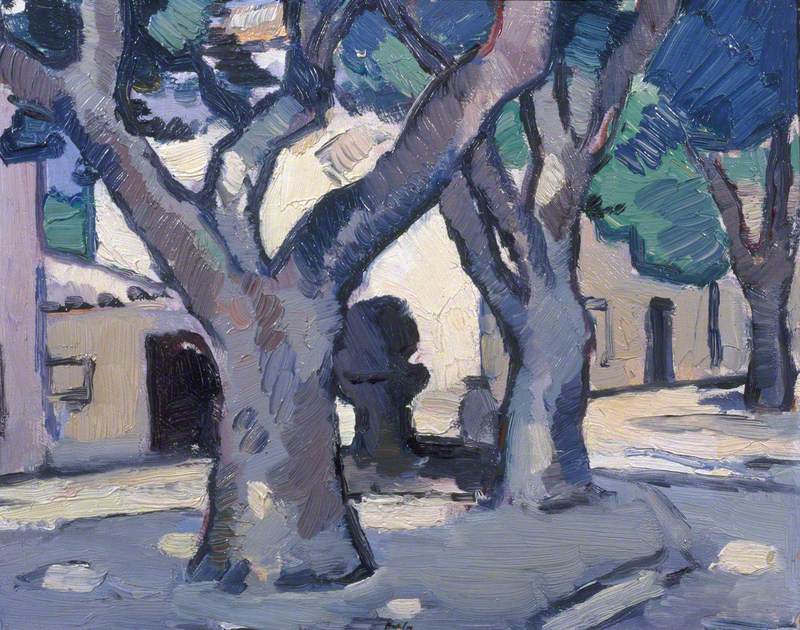

Scottish artist Alexander Goudie (1933–2004) was obsessed with witchcraft and Nannie Dee. He created a series of over 50 paintings that illustrate the poem, and they are now housed in South Ayrshire at the Rozelle House Galleries. Here's a small selection of them, alongside the parts of the poem they represent.

For those of you who struggle to read some of the Scots dialect words, we've provided a modern English translation.

When chapman billies leave the street,

And drouthy neibors, neibors, meet;

As market days are wearing late,

And folk begin to tak the gate,

[drouthy = thirsty]

While we sit bousing at the nappy,

An' getting fou and unco happy,

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps and stiles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Where sits our sulky, sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

[bousing at the nappy = boozing on strong ale]

[getting fou and unco happy = getting drunk and very happy]

This truth fand honest Tam o' Shanter,

As he frae Ayr ae night did canter:

(Auld Ayr, wham ne'er a town surpasses,

For honest men and bonie lasses).

[fand = find, frae = from, auld = old]

O Tam! had'st thou but been sae wise,

As taen thy ain wife Kate's advice!

She tauld thee weel thou was a skellum,

A blethering, blustering, drunken

[sae = so,

Ah, gentle dames! it gars me greet,

To think how

How

The husband

The wind blew as '

The rattling showers rose on the blast;

The speedy gleams the darkness

Loud, deep, and lang, the thunder

That night, a child might understand,

The

[deil = devil]

Weel-mounted on his grey mare, Meg,

A better never lifted leg,

Tam

Despising wind, and rain, and fire;

[weel-mounted = well mounted,

Kirk-Alloway

Thro' ilka bore the beams were glancing,

And loud resounded mirth and dancing.

[bleeze = blaze]

Warlocks and witches in a dance,

Nae cotillon, brent new

But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels,

Put life and mettle in their heels.

[Nae cotillon brent new

Coffins stood round, like open presses,

That

And (by some devilish cantraip sleight)

Each in its

[cantraip = magic]

Tam tint his reason a

And roars out, "

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had he Maggie rallied.

When out the hellish legion sallied.

[Tam tint his reason a

When "Catch the thief!" resounds aloud;

So Maggie runs, the witches follow,

Wi'

[Wi’mony an eldritch

A running stream they dare

But ere the

The

[keystane = keystone]

But little wist she Maggie's mettle!

Ae spring brought off her master hale,

But left behind her ain grey tail:

The carlin

And left poor Maggie scarce a stump.

[

Now,

Ilk man and mother's son, take heed:

Or cutty-sarks rin in your mind,

Think ye may buy the joys o'er dear;

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mare.

[Ilk = each, or cutty-sarks rin in your mind = or short skirts run in your mind]

So, is there a moral at the end of Tam o' Shanter? Based on the superstitions found in Scottish folklore at the end of the eighteenth century, Burns' epic tale is a humorous reminder that all pleasures in life are precious and fleeting – 'but pleasures are like poppies spread: you seize the flower, its bloom is shed'.

It reminds us that we all pay for the consequences of our actions, even those foolish, drunken mistakes (like heckling women – even if they are witches – in short skirts). One interpretation is that Burns was encouraging foolhardy men to listen to their sensible wives – their prophecies are usually right.

You can read the full poem on the BBC website and listen to it read by Scottish actor Brian Cox.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK