Eileen Agar (1899–1991) was 80 years old when she painted Bride of the Sea (1979). Combining an abstract approach with cut-out effects, she filled the huge canvas with female faces, geometrically patterned fish, the outline of trawl nets and vivid planes of blue. Evoking a majestic ship on the ocean, the composition not only demonstrates the artist's lifelong commitment to Surrealism but her deep interest in the symbolism of the sea.

Ahead of a major retrospective 'Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy' at London's Whitechapel Gallery, let's dive into the world of this pioneering female Surrealist, whose unique marine symbolism can be found across her paintings, assemblages and fashion designs.

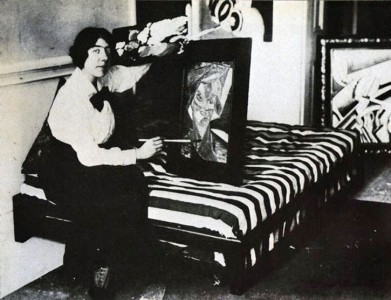

When the International Surrealist Exhibition opened in London on 11th June 1936, audiences were shocked and delighted by the display of almost 400 surreal artworks. Among those on show were three oil paintings and five found objects by Agar, who was one of few female artists to be included. The exhibition, which launched Surrealism in Britain, also introduced Agar as a star member of the movement: 'I became a Surrealist almost overnight', she recalled.

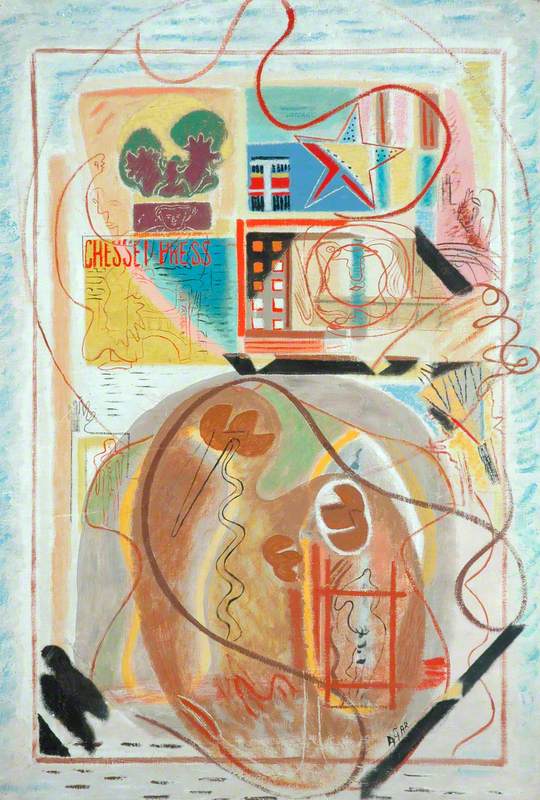

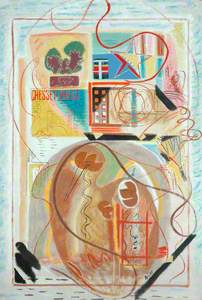

In many ways, Agar was a reluctant Surrealist: 'I am suspicious about the whole idea of working from dreams', she once explained. This hesitancy is evident in Untitled (1936), in which expressive, free-flowing lines echo the automatic drawing techniques adopted by many Surrealists to allow the subconscious to take control. At the same time, Agar maintained a level of control in the defined and intentionally layered images, evoking her interest in Cubist collage.

Untitled not only shows Agar combining Cubist and Surrealist approaches within her work. The painting also displays the artist's early inclusion of several motifs that remained significant for the rest of her life: among the drawn shapes are a starfish and, framing the composition, ripples of blue water. This aquatic imagery indicates that Agar's inspiration came not from dreams, but from the sea.

Although Agar was a dubious Surrealist, she perceived an unforced and organic surreality in the world around her. As she accounted: 'Surrealism for me draws its inspiration from Nature...you see the shape of a tree, the way a pebble falls or is framed, and you are astounded to discover that dumb nature makes an effort to speak to you, to give you a sign, to warn you, to symbolise your innermost thoughts.'

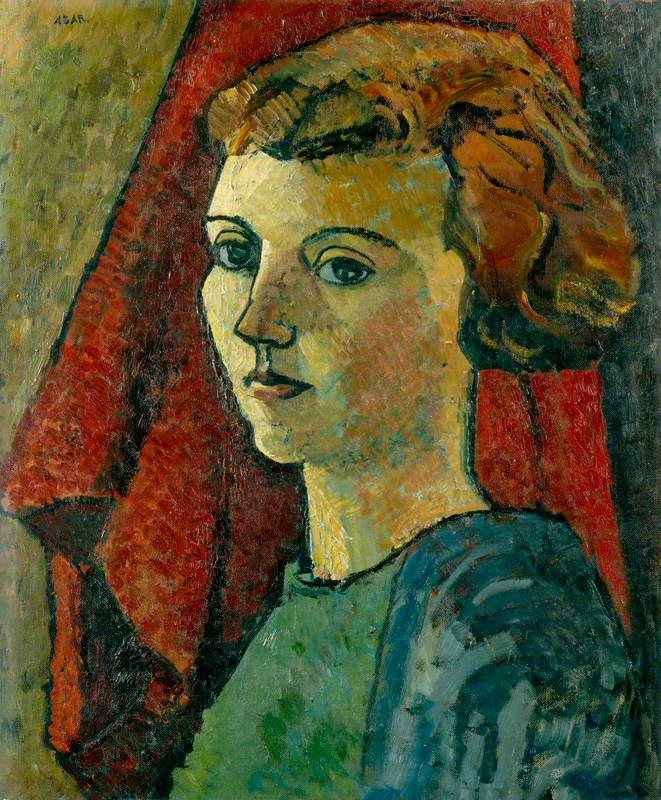

Agar's interest in the natural world came, in part, from her childhood. Born in Argentina's capital city, Buenos Aires, to a Scottish father and an American mother, Agar enjoyed spending most of her time playing outside. But by the 1930s, from the age of six, Agar was living in England and attended boarding school. She went on to study at London's prestigious Slade School of Fine Art between 1925 and 1926.

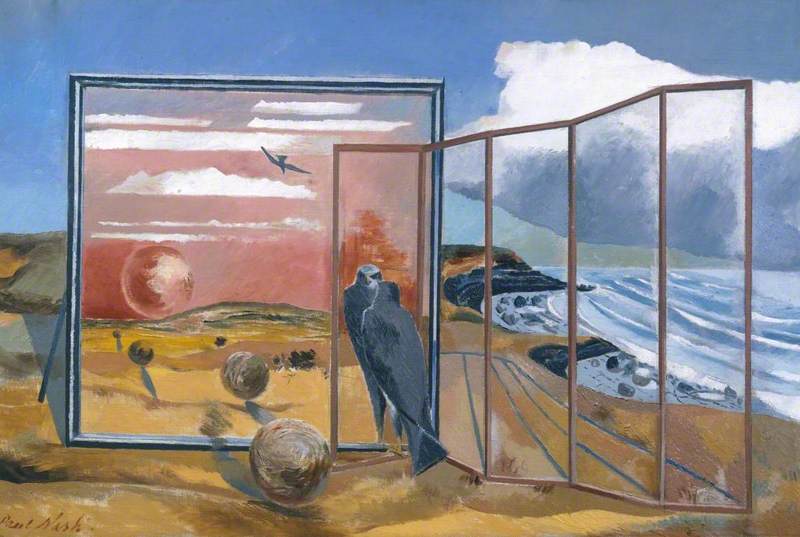

From her new home in London, Agar loved to travel, both around the UK and further afield. During these trips, she became an avid beachcomber. From the coastlines of Cornwall, Cumbria and France, the artist collected shells, stones, starfish, bones and other marine detritus, stating that these 'forms of Nature to a painter are studies in pure abstract design'. In 1936, while on holiday in Dorset, Agar met the artist Paul Nash, and the pair, encouraging one another, searched the beach for objects to potentially study, but which could also be exhibited as natural Surrealist sculptures in their own right.

From the very start of the movement, the 'found object', or objet trouvé, was hugely important to the Surrealists, who juxtaposed incongruous items in order to tap into the subconscious and create a new reality. In Meret Oppenheim's iconic Luncheon in Fur (1934), a teacup, saucer and spoon are adorned in fur.

Reimagine the everyday things around us

— MoMA The Museum of Modern Art (@MuseumModernArt) April 20, 2020

Meret Oppenheim brought familiar items into disturbing and humorous juxtaposition. The artist's fur-lined teacup seems attractive to the touch—if not to the taste. Read a poem exploring "Object"'s eroticism: https://t.co/CDR4fYA3m9 pic.twitter.com/i4piNxeyrS

Similarly, Agar discovered in the found object an opportunity, which she referred to as 'a displacement of the banal by the fertile intervention of chance or coincidence'.

However, in contrast to many of her contemporaries, who bought cheap items at flea markets, or used mundane mass-produced objects, Agar preferred to find organic bounty on the beach. This liminal site, existing on the boundary between land and ocean, was the ideal location for her to discover, by chance, naturally surreal objects thrown up by the sea. Some, Agar showed unmodified and as she found them, though others were assembled into works such as Fish Basket (c.1965), comprised of a wicker basket, a shrimp and a shell, positioned on a cardboard base.

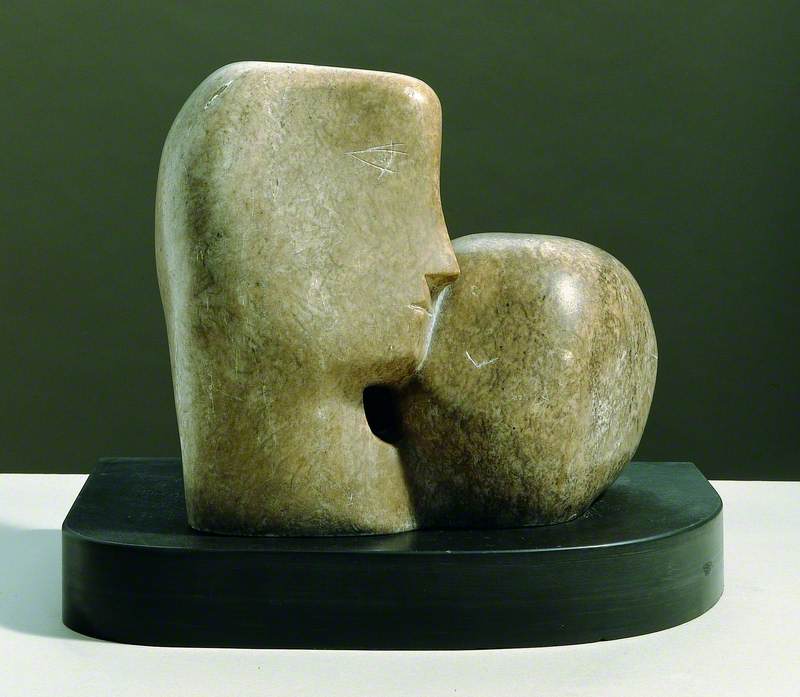

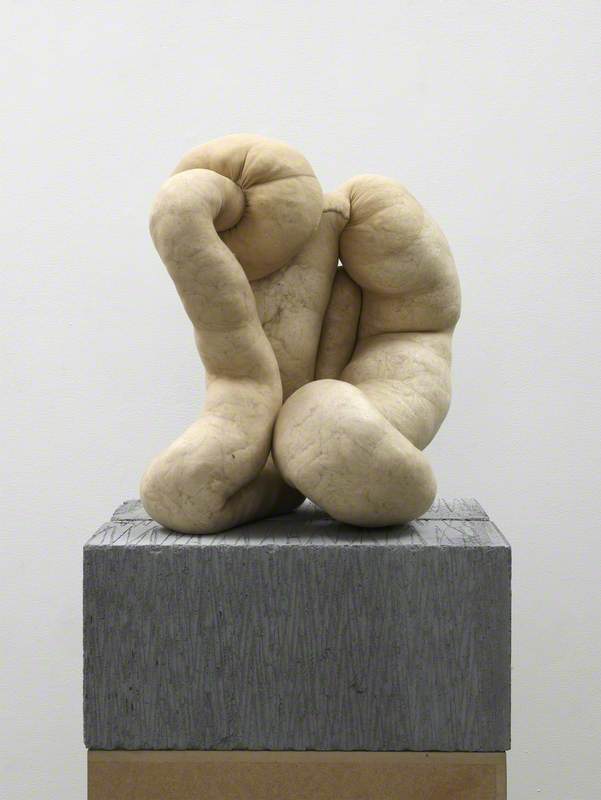

Agar also used mysterious marine matter to construct one of her most iconic artworks, Angel of Anarchy (1936–1940). Since childhood, Agar remembered being 'rebellious', a quality she never lost in her life and art. Indeed, she was known to have anarchist sympathies. In this assemblage, she deliberately combined order with theatrical chaos, emphasised by the title. The blindfolded plaster cast head has been encased in sea-shells, feathers, silk fabric and stones to create a work she described as 'powerful' and 'malign'.

Angel of Anarchy

1936–1940, plaster, fabric, shells, beads, diamante stones & other materials by Eileen Agar (1899–1991)

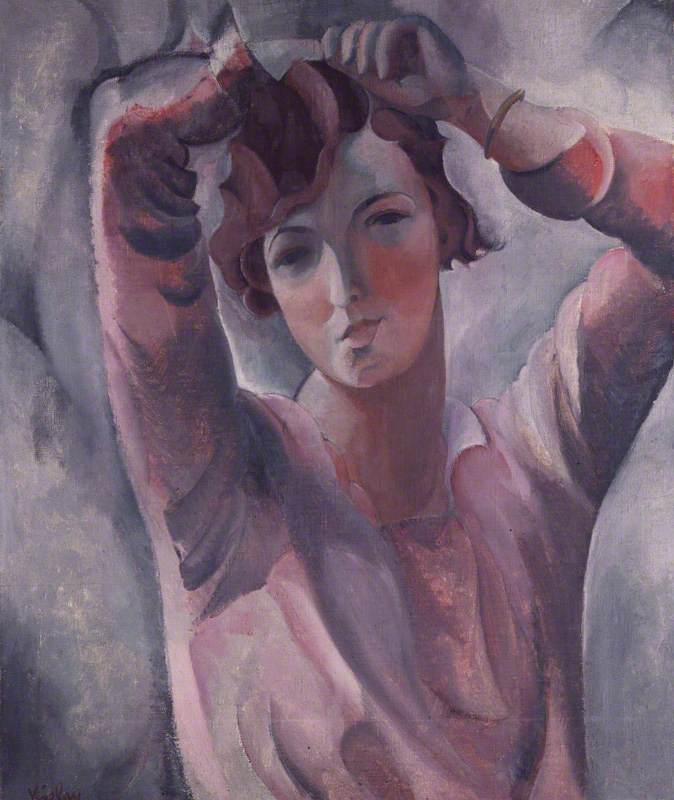

The angel is a recurring symbol in the work of the female Surrealists, who also used themselves as their own muses, and as a way to celebrate their creativity. While women were welcomed into Surrealism, it was often initially as models, and they were frequently positioned as the site of erotic desire – a source of inspiration for their male counterparts. It was Agar who once pointed out that female artists were 'expected to behave as the great man's muse, not to have an active creative existence'.

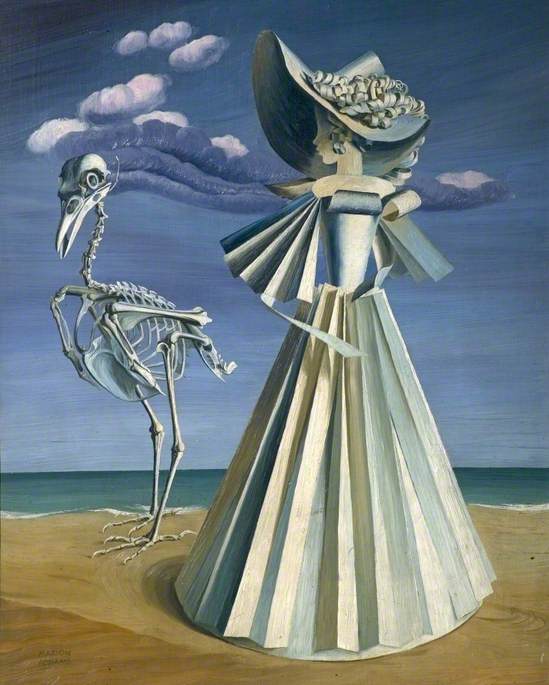

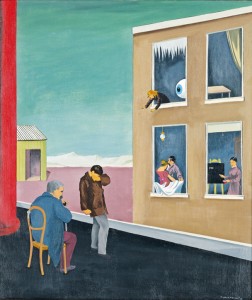

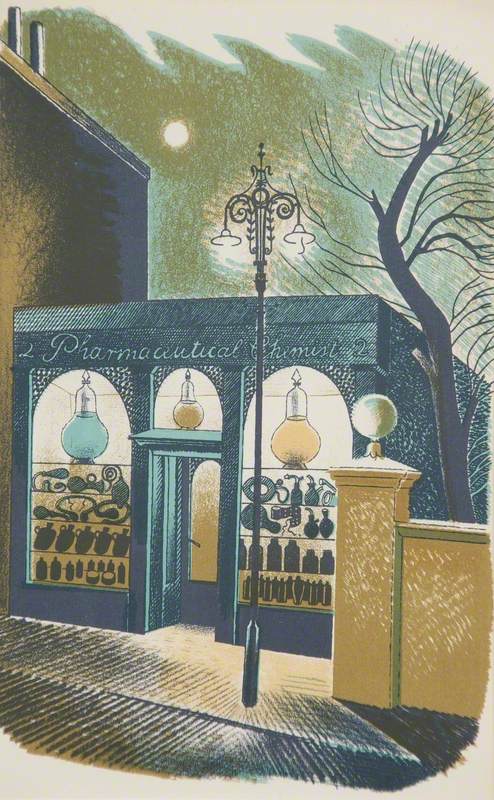

The female Surrealists, therefore, created a visual vocabulary with which they could reclaim their role as artists and women with desires of their own. Many women associated with the movement, including Marion Adnams, Ithell Colquhoun and Emmy Bridgwater, turned to magic, myth and the fantastical natural world, which existed beyond the realm of their male counterparts, for inspiration. Imagery of Mother Earth, alchemy, the occult, animals and birds populate uncanny works, such Adnam's enchanted beach scene, Alter Ego (c.1940).

Similarly, Agar observed an appropriate Surrealist language in the sublime and almost supernatural depths of the sea. The artist's painting Collective Unconscious (1977–1978) is composed of semi-abstracted forms drawn from shells, sea anemones, seaweed and fossils. Overlapping and intertwined, and imagined in a palette of brilliant colours, these shapes seem to emerge from an almost bottomless ocean of the mind – a reading confirmed by the title.

Agar's later work from 1979, Bride of the Sea, also seems to be a reflection on creativity, represented through the imagery of a vast, swelling sea and its fluid forms.

Discover the beauty and history of the south coast through a virtual journey from Portsmouth to Gosport. Curated by Gosport MP & Minister for Digital & Culture @cj_dinenage @DCMS, it features @GovArtCol's 'Bride of the Sea' by Eileen Agar https://t.co/nAcVB2bDVj #ArtCurations pic.twitter.com/NH7QZJBBC0

— Govmt Art Collection (@GovArtCol) July 14, 2020

Through its title, Agar highlights the associations between the sea and a specifically feminine creative power – the composition includes the silhouetted face of a woman which doubles as the bow of a ship sailing across the ocean.

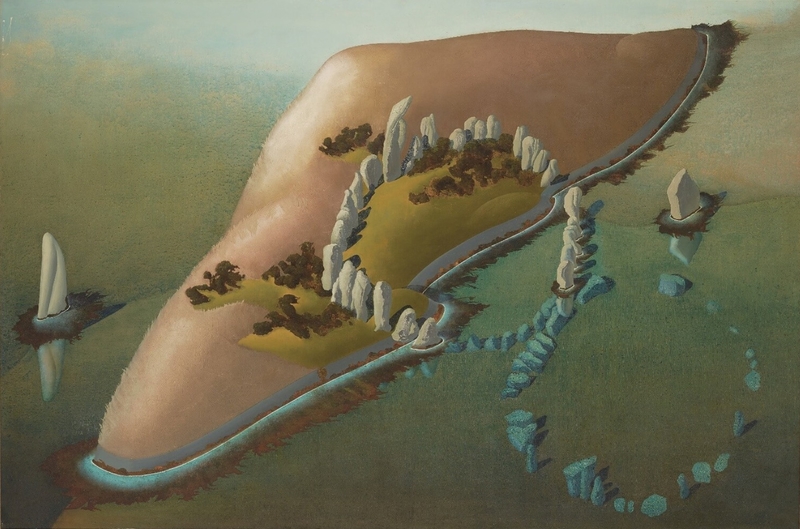

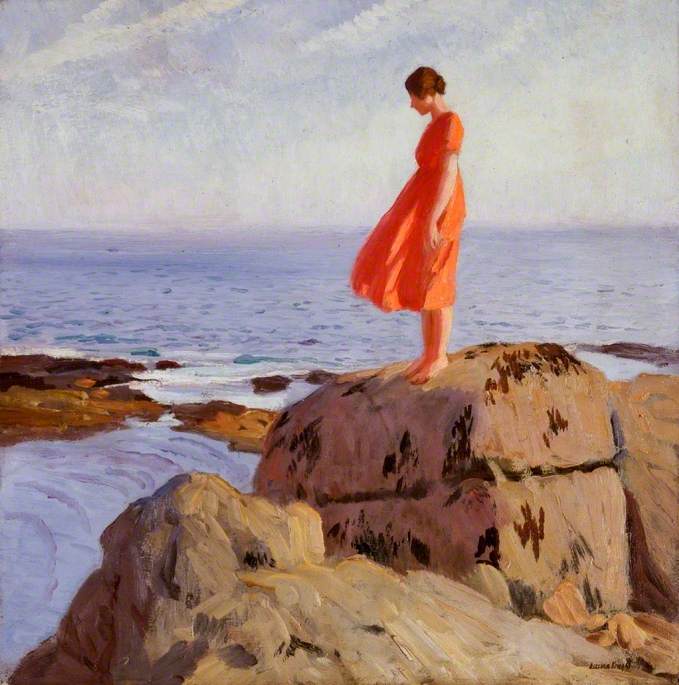

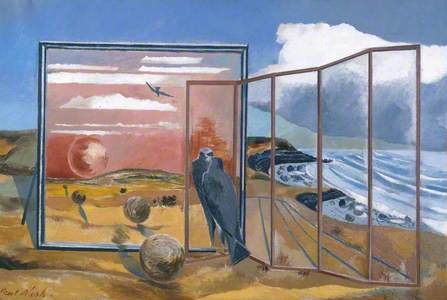

Similarly, in her painting Scylla (1938) Ithell Colquhoun plays with the idea of a feminine supremacy associated with the sea.

Her title references a female monster from ancient Greek mythology which lived upon the rocks in a narrow stretch of water and preyed on passing sailors. Colquhoun used the image of her own body in the bath, including her knees which stand for the rock formations jutting out of the water: 'It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath... it is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image'.

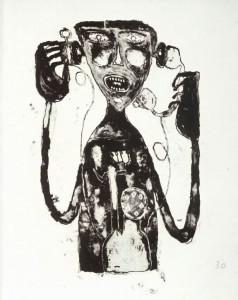

Male artists did also turn to the sea for inspiration, and most famously Salvador Dalí. Most famously, he created a notoriously phallic lobster balanced on a telephone, titled simply Lobster Telephone (1936).

Then, in 1939, he designed a pavilion for the New York World's Fair built called Dream of Venus, a Surrealist realm in which topless women posed as mermaids. In contrast to these sexualised images of the sea and its creatures, the female Surrealists positioning it as a force of ancient, anarchic and feminine power.

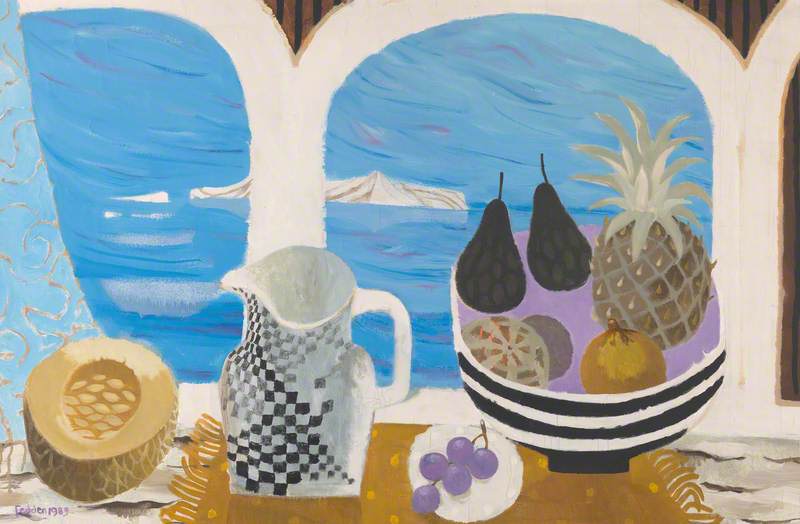

At the same time, Agar demonstrated a more playful embrace of the symbolism of the sea through her trailblazing experiments in Surrealist fashion design. One such example is Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse (1936) which the artist created during a trip to St Tropez in the South of France.

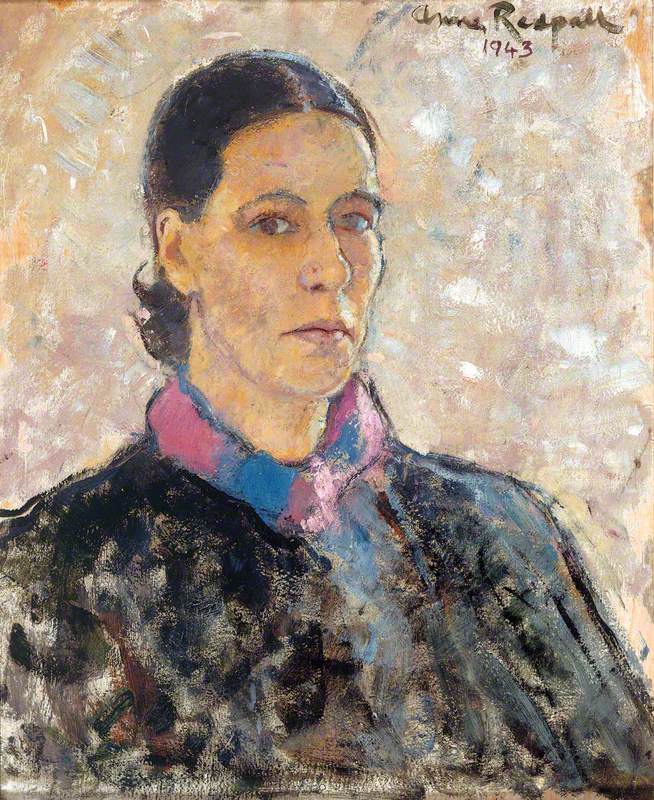

Photographs of Agar wearing 'Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse'

1936, photograph by unknown artist, private collection

Using objects located on the seashore, including a cork basket which she painted blue, a fishnet, a lobster's tail and a starfish, the artist devised what she later described as 'a sort of Arcimboldo headgear for the fashion-conscious'. Dressing herself in the surreal design, she recalled receiving 'a lot of rather startled publicity' for it.

In her autobiography A Look at my Life (1988), Agar wrote that as an artist 'one must have a hunger for new colour, new shapes and new possibilities of discovery'.

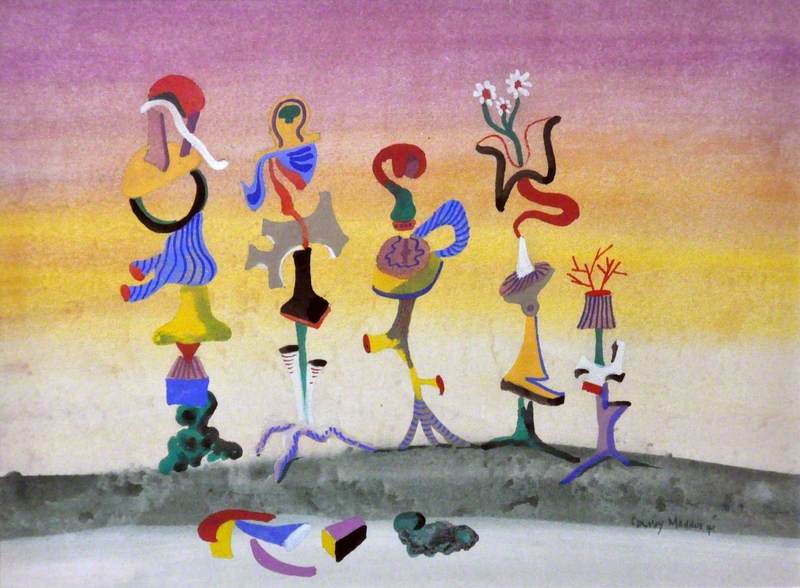

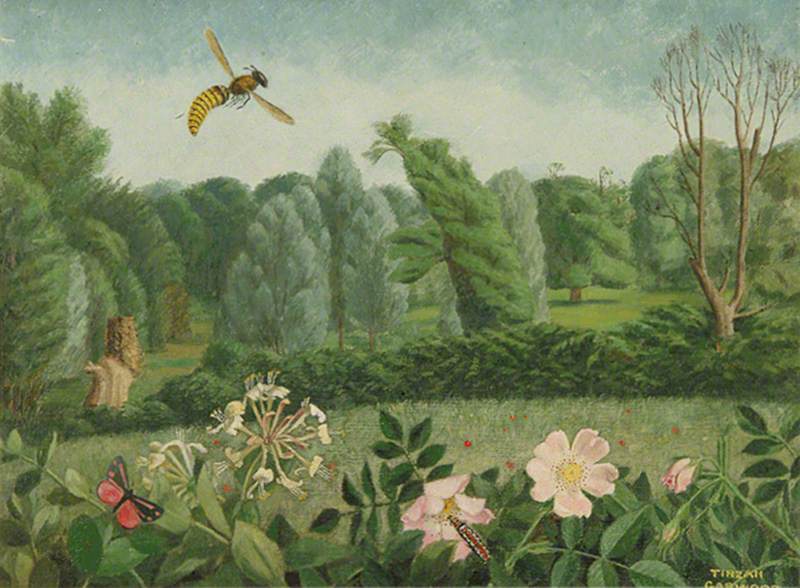

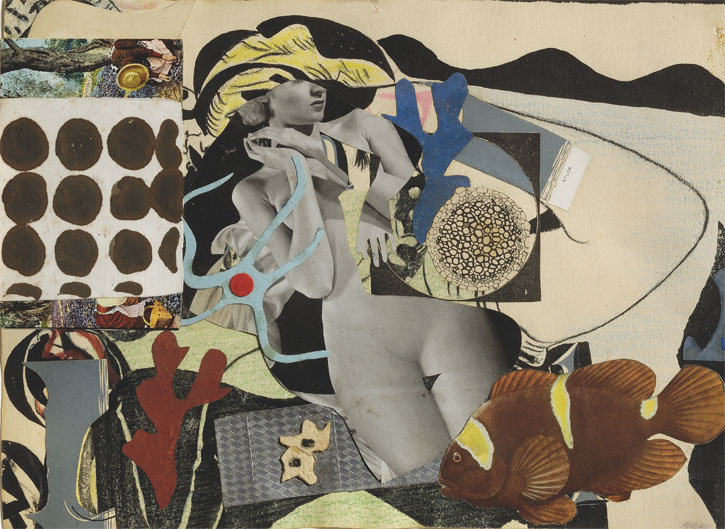

Erotic Landscape

1942, collage on paper by Eileen Agar (1899–1991), private collection

The sea was a powerful source of inspiration for Agar, providing her with Surrealist bounty which she could exhibit as found objects, transform into assemblages or use to decorate revolutionary hats. In her paintings, the unfathomable ocean also acts as an expression of the subconscious mind and creativity, beyond all boundaries.

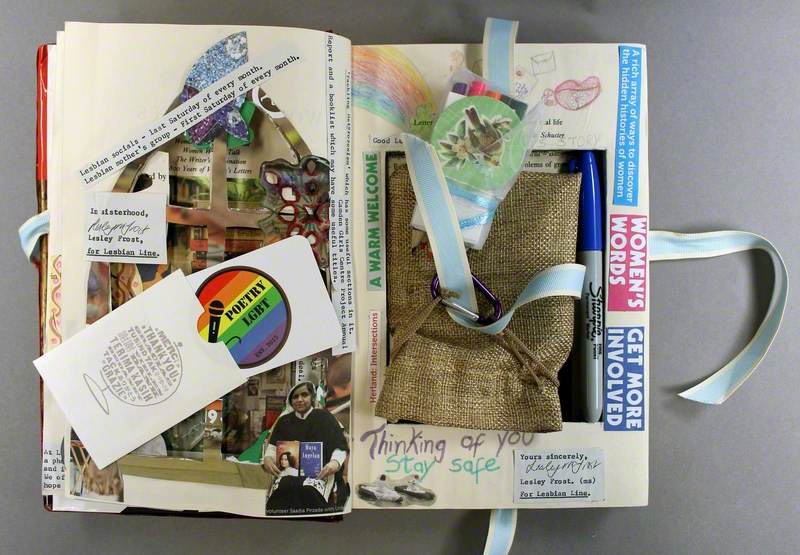

The upcoming retrospective at London's Whitechapel Gallery will be the largest exhibition of Agar's work to date and celebrates the crucial role that she played within the development of Surrealism and European twentieth-century culture at large. Featuring over 100 paintings, collages, photographs, assemblages and archival material, much of which has been rarely exhibited, the show demonstrates Agar's rebellious and transformative approach to art inspired by everyday objects, which in her own words encapsulates: 'the quality of magic that I must reveal to this world of sleepers'.

Ruth Millington, art critic and writer

'Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy' will run from 19th May to 29th August 2021 at Whitechapel Gallery, London

Further reading

Dawn Ades, 'Notes on Two Women Surrealist Painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun', Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, (pp.36–42), 1980

Eileen Agar and Andrew Lambirth, A Look at My Life, Methuen, 1988

David Boyd Haycock, Sacha Llewellyn and Kirstie Meehan, British Surrealism, Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2020

Demond Morris, The Lives of the Surrealists, Thames and Hudson, 2018

Michel Remy, Surrealism in Britain, Lund Humphries, 1999